- Oneida Indian Nation of N.Y. State v. Oneida Cnty.

-

Oneida Indian Nation of N.Y. State v. Oneida Cnty.

Supreme Court of the United StatesArgued Nov. 6 and 7, 1973

Decided Jan. 21, 1974Full case name Oneida Indian Nation of New York State v. Oneida County, New York, et al. Citations 414 U.S. 661 (more)

94 S. Ct. 772, 39 L. Ed.2d 73Prior history 464 F.2d 916 (2d Cir. 1972), cert. granted 412 U.S. 927 (1973) Subsequent history On remand to, 434 F. Supp. 527 (N.D.N.Y. 1977), aff'd, 719 F.2d 525 (2d Cir. 1983), cert. granted, 465 U.S. 1099 (1984), aff'd in part, rev'd in part, Oneida Cnty. v. Oneida Indian Nation of N.Y. State, 470 U.S. 226 (1985), rehearing denied, 471 U.S. 1062 (1985), on remand, 217 F. Supp. 2d 292 (N.D.N.Y. 2002), motion for relief denied, 214 F.R.D. 83 (N.D.N.Y. 2003), motion for relief granted after remand, 2003 WL 21026573 (N.D.N.Y. 2003) Holding There is federal subject-matter jurisdiction for possessory land claims brought by Indian tribes based upon aboriginal title, the Nonintercourse Act, and Indian treaties Court membership Chief Justice

Warren E. BurgerAssociate Justices

William O. Douglas · William J. Brennan, Jr.

Potter Stewart · Byron White

Thurgood Marshall · Harry Blackmun

Lewis F. Powell, Jr. · William RehnquistCase opinions Majority White Concurrence Renquist, joined by Powell Laws applied 28 U.S.C. §§ 1331, 1362 Oneida Indian Nation of N.Y. State v. Oneida Cnty., 414 U.S. 661 (1974), is a landmark decision concerning aboriginal title in the United States. The suit was the "first of the modern-day [Native American land] claim cases to be filed in federal court."[1] By allowing such claims to proceed in federal court, Oneida I "overturned one hundred forty-three years of American law."[2]

The Supreme Court held that there is federal subject-matter jurisdiction for possessory land claims brought by Indian tribes based upon aboriginal title, the Nonintercourse Act, and Indian treaties. The case re-invigorated Indian land claims in the eastern United States, especially the former Thirteen Colonies, with the hope of a federal forum for claims which had been un-litigable in state courts for 200 years.

Justice White held that jurisdiction for such suits arose both from 28 U.S.C. § 1331—conferring jurisdiction for cases "aris[ing] under the Constitution, laws, or treaties of the United States"—and 28 U.S.C. § 1362—conferring similar jurisdiction to cases brought by Indian tribes, regardless of the amount in controversy.

The case is often referred to as Oneida I because it is the first of three times the Oneida Indian Nation reached the Supreme Court in litigating its land rights claims. It was followed by Oneida Cnty. v. Oneida Indian Nation of N.Y. State (1985) ["Oneida II"]—rejecting all of the affirmative defenses raised by the counties in the same action, and City of Sherrill v. Oneida Indian Nation of N.Y. (2005) ["Sherrill"], rejecting the tribe's attempt in a later lawsuit to re-assert tribal sovereignty over parcels of land re-acquired by the tribe in fee simple.

Contents

Background

Further information: Aboriginal title in New YorkPrior history

District Court

In 1970, the Oneida Indian Nation of New York State and Oneida Indian Nation of Wisconsin filed suit against Oneida County, New York and Madison County, New York in the United States District Court for the Northern District of New York. The Oneidas alleged that vast swathes of tribal lands had been conveyed to the state of New York in violation of the Nonintercourse Act and three Indian treaties: the Treaty of Fort Stanwix (1784), the Treaty of Fort Harmar (1789), and the Treaty of Canandaigua (1794). Although the complaint named over 6,000,000 acres (24,000 km2) conveyed in such manner, the suit involved only the portion of that land held by the two counties. As damages, the tribes asked only for the fair rental value of the lands from the period January 1, 1968, through December 31, 1969.

The District Court held that the complaint asserted only state law claims, implicating federal law only indirectly, and thus granted the motion to dismiss under the well-pleaded complaint rule.

Circuit Court

A divided panel of the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit affirmed the dismissal. Chief Judge Henry Friendly, for the Second Circuit, held that the assertion of jurisdiction "shatters on the rock of the ‘well-pleaded complaint’ rule." The Second Circuit placed weight upon Taylor v. Anderson, 234 U.S. 74 (1914), holding that there was no federal jurisdiction for an ejectment action which alleged wrongful alienation of lands allotted to Choctaw and Chickasaw Indians.

Opinion

Majority

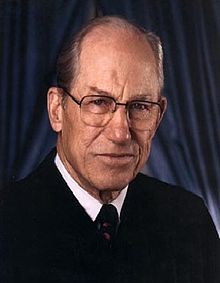

Justice Byron White, the author of Oneida I

Justice Byron White, the author of Oneida I

The Supreme Court reversed. Justice White noted that, "[a]ccepting the premise of the Court of Appeals that the case was essentially a possessory action, we are of the view that the complaint asserted a current right to possession conferred by federal law, wholly independent of state law."[3] The Court distinguished Taylor v. Anderson on the grounds that:

Here, the right to possession itself is claimed to arise under federal law in the first instance. Allegedly, aboriginal title of an Indian tribe guaranteed by treaty and protected by statute has never been extinguished. In Taylor, the plaintiffs were individual Indians, not an Indian tribe; and the suit concerned lands allocated to individual Indians, not tribal rights to lands . . . .

In the present case, however, the assertion of a federal controversy does not rest solely on the claim of a right to possession derived from a federal grant of title whose scope will be governed by state law. Rather, it rests on the not insubstantial claim that federal law now protects, and has continuously protected from the time of the formation of the United States, possessory rights to tribal lands, wholly apart from the application of state law principles which normally and separately protect a valid right of possession.[4]The majority emphasized the supremacy of federal Indian law to state law:

There has been recurring tension between federal and state law; state authorities have not easily accepted the notion that federal law and federal courts must be deemed the controlling considerations in dealing with the Indians. Fellows v. Blacksmith, The New York Indians, United States v. Forness, and the Tuscarora litigation are sufficient evidence that the reach and exclusivity of federal law with respect to reservation lands and reservation Indians did not go unchallenged; and it may be that they are to some extent challenged here. But this only underlines the legal reality that the controversy alleged in the complaint may well depend on what the reach and impact of the federal law will prove to be in this case.[5]

Because the District Court had disposed on the case on a motion to dismiss, the Supreme Court reversed and remanded for further proceedings.

Concurrence

Justices Rehnquist and Powell concurred separately, emphasizing their understanding that the majority's holding would not apply to ejectment actions brought by non-Indians. The concurrence concluded: "The opinion for the Court today should give no comfort to persons with garden-variety ejectment claims who, for one reason or another, are covetously eyeing the door to the federal courthouse."[6]

Further history

Main article: Oneida Cnty. v. Oneida Indian Nation of N.Y. StateOn remand, the District Court and Second Circuit rejected the counties' affirmative defenses and awarded money damages. This time, the counties appealed to the Supreme Court, which again granted certiorari. The impact of Oneida I was summed up, in the interpretation of Allan Van Gestal, the lawyer for Oneida County, in his argument in Oneida II:

This case is a test case, having been so designated by the plaintiffs, having been so tried by the courts below. . . . The 1974 opinion in this case has already spawned a vast number of Indian land claims. A number of cases are pending throughout the eastern states and southern states, citing the 1974 jurisdictional opinion as if it were an opinion on the merits of the issues. That case, indeed, has already been cited 162 times since 1974.[7]

Oneida Cnty. v. Oneida Indian Nation of N.Y. State, 470 U.S. 226 (1985), affirmed the rejection of the counties' affirmative defenses, leaving the damages award intact. The larger portion of the Oneida claim, to the 6-million-acre (24,000 km2) tract, was rejected by the Second Circuit in 1988, on the grounds that the Confederation Congress Proclamation of 1783 had neither the authority nor the intent to limit the acquisition of Indian lands within the borders of U.S. states.[8]

Notes

- ^ Vecsey & Starna, 1988, at 144.

- ^ Laurence M. Hauptman, Seneca Nation of Indians v. Christy: A Background Story, 46 Buffalo L. Rev. 947, 947 (1998).

- ^ 414 U.S. at 666.

- ^ 414 U.S. at 676–77.

- ^ 414 U.S. 678–79.

- ^ 414 U.S. at 684.

- ^ "County Of Oneida v. Oneida Indian Nation - Oral Argument". oyez.org. http://www.oyez.org/cases/1980-1989/1984/1984_83_1065/argument. Retrieved 18 October 2010.

- ^ Oneida Indian Nation of New York v. New York, 860 F.2d 1145 (2d Cir. 1988).

References

- Kristina Ackley, Renewing Haudenosaunee Ties: Laura Cornelius Kellogg and the Idea of Unity in the Oneida Land Claim, 32 Am. Indian Culture & Res. J. 57 (2008).

- John Edward Barry, Comment, Oneida Indian Nation v. County of Oneida: Tribal Rights of Action and the Indian Trade and Intercourse Act, 84 Colum. L. Rev. 1852 (1984).

- Jack Campisi, The New York-Oneida Treaty of 1795: A Finding of Fact, 4 Am. Indian L. Rev. 71 (1976).

- Kathryn E. Fort, Disruption and Impossibility: The Unfortunate Resolution of the Iroquois Land Claims in Federal Courts (Mich. State Univ. Law Sch. Res. Paper No. 09-03, 2011).

- Joshua N. Lief, The Oneida Land Claims: Equity and Ejectment, 39 Syracuse L. Rev. 825 (1988).

- George C. Shattuck, The Oneida Land Claims: A Legal History (1991).

- Christopher Vecsey & William A. Starna, Iroquois land claims (1988).

External links

Aboriginal title in the United States Statutes Colonial era: Charter of Freedoms and Exemptions (1629; New Netherland) Royal Proclamation of 1763 (British North America) · Confederation Congress Proclamation of 1783 · Northwest Ordinance (1787) · Nonintercourse Act (1790, 1793, 1796, 1799, 1802, and 1834) · Removal Act (1830) · Dawes Act (1887) · Curtis Act of 1898 · Reorganization Act (1934) · Indian Claims Commission Act (1946) · Indian Land Claims Settlements (1978—2006) · Indian Claims Limitations Act (1982)

Precedents Marshall Court: Johnson v. M'Intosh (1823); Cherokee Nation v. Georgia (1831) · Taney Court: Fellows v. Blacksmith (1857); New York ex rel. Cutler v. Dibble (1858) · Seneca Nation of Indians v. Christy (1896) · United States v. Santa Fe Pac. R.R. (1941) · Warren Court: Tee-Hit-Ton Indians v. United States (1955); Fed. Power Comm'n v. Tuscarora Indian Nation (1960) · Burger Court: Oneida Indian Nation of N.Y. State v. Oneida Cnty. (1974); Oneida Cnty. v. Oneida Indian Nation of N.Y. State (1985); South Carolina v. Catawba Indian Tribe (1986) · Rehnquist Court: Idaho v. Coeur d'Alene Tribe of Idaho (1997); Idaho v. United States (2001); City of Sherrill v. Oneida Indian Nation of N.Y. (2005)By state Alaska · California · Hawaii · Indiana · Louisiana · Maine · New Mexico · New York · Rhode Island · VermontCompare Oneida people Groups

Oneida Indian Nation · Oneida Nation of Wisconsin · Oneida Nation of the ThamesHistory and Culture

Oneida language · Iroquois Confederacy · Treaty of CanandaiguaLitigation

Oneida Indian Nation of N.Y. State v. Oneida Cnty. (1974) · Oneida Cnty. v. Oneida Indian Nation of N.Y. State (1985) · City of Sherrill v. Oneida Indian Nation of N.Y. (2005)Categories:- Flagged U.S. Supreme Court articles

- United States Supreme Court cases

- Aboriginal title case law in the United States

- Federal question jurisdiction case law

- Oneida

- Aboriginal title in New York

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.