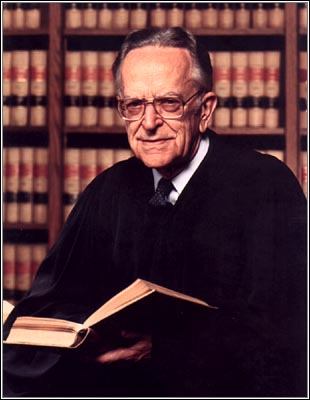

- Harry Blackmun

Infobox Judge

name = Harry Andrew Blackmun

imagesize =

caption =

office = Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court

termstart =June 9 1970

termend =August 4 1994

nominator =Richard Nixon

appointer =

predecessor =Abe Fortas

successor =Stephen Breyer

office2 =

termstart2 =

termend2 =

nominator2 =

appointer2 =

predecessor2 =

successor2 =

birthdate = birth date|1908|11|12

birthplace = Nashville,Illinois

deathdate = death date and age|1999|3|4|1908|11|12

deathplace =Arlington, Virginia

spouse =Harry Andrew Blackmun (

November 12 ,1908 –March 4 ,1999 ) was anAssociate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1970 to 1994. He is best known as the author of the majority opinion in the 1973 "Roe v. Wade " decision, overturning laws restrictingabortion in theUnited States and declaringabortion protected under a constitutional right to privacy.Early years and professional career

Harry Blackmun was born in

Nashville, Illinois , and grew up inDayton's Bluff , a working-class neighborhood inSaint Paul, Minnesota . He attendedHarvard College on scholarship, earning abachelor's degree inmathematics "summa cum laude"Phi Beta Kappa in 1929 . While at Harvard, Blackmun joinedLambda Chi Alpha Fraternity and sang with theHarvard Glee Club . He attendedHarvard Law School (among his professors there wasFelix Frankfurter ), graduating in 1932. He served in a variety of positions including private counsel, law clerk, and adjunct faculty at theUniversity of Minnesota and the St Paul College of Law (now calledWilliam Mitchell College of Law ). Blackmun's practice as an attorney at the law firm now known asDorsey & Whitney focused in its early years on taxation,trusts and estates , andcivil litigation . He married Dorothy Clark in 1941 and had three daughters with her, Nancy, Sally, and Susan. Between 1950 and 1959 Blackmun served as resident counsel for theMayo Clinic inRochester, Minnesota .Appellate bench

President

Dwight David Eisenhower appointed Blackmun to theUnited States Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit on4 November 1959 . Blackmun's opinions on the circuit court level were mainly tax-related,Fact|date=August 2008 although he wrote influential opinions about other matters, including "Jackson v. Bishop " (1968), which was probably the first appellate opinion to declare that physical abuse of prisoners was cruel and unusual punishment under the Constitution.Blackmun's tenure on the Supreme Court

Blackmun was nominated for the Supreme Court by

Richard Nixon on4 April 1970 , and was confirmed by theUnited States Senate later the same year. His confirmation followed contentious battles over two previous, failed nominations forwarded by Nixon in 1969-1970, those ofClement Haynsworth andG. Harrold Carswell . Blackmun's nomination sailed through the Senate with no opposition on17 May 1970 .Early years on the Supreme Court

Blackmun, a lifelong Republican, was generally expected to adhere to a conservative interpretation of the Constitution. The Court's Chief Justice at the time,

Warren Burger , a long-time friend of Blackmun's and at whose wedding Blackmun wasbest man , had recommended Blackmun for the job to PresidentRichard M. Nixon . The two were often referred to as the "Minnesota Twins" (a reference to the baseball team, theMinnesota Twins ) because of their common history in Minnesota and because they so often voted together. Indeed, in 1972 Blackmun joined Burger and the other two Nixon appointees to the Court in dissenting from the "Furman v. Georgia " decision that invalidated allcapital punishment laws then in force in the United States, and in 1976 he voted to reinstate the death penalty in 1976's "Gregg v. Georgia ", even the mandatory death penalty statutes, although in both instances he indicated his personal opinion of its shortcomings as a policy. Blackmun, however, insisted his political opinions should have no bearing on the death penalty's constitutionality.Blackmun voted with Burger in 87.5 percent of the closely-divided cases during his first five terms (1970 to 1975), and with Brennan, the Court's leading liberal, in only 13 percent. [Greenhouse, Linda. Becoming Justice Blackmun. Times Books. 2005. Page 186.] By the next five-year period, Blackmun was joining Brennan in 54.5 percent of the divided cases, and Burger in 45.5 percent. [Greenhouse, Linda. Becoming Justice Blackmun. Times Books. 2005. Page 186.] During the final five years that Blackmun and Burger served together, Blackmun joined Brennan in 70.6 percent of the close cases, and Burger in only 32.4 percent. [Greenhouse, Linda. Becoming Justice Blackmun. Times Books. 2005. Page 186.]

Blackmun and abortion

A turning point came in 1973. That year the Court's opinion in the case of "

Roe v. Wade " which he authored was handed down. "Roe" invalidated a Texas statute making it afelony to administer anabortion in most circumstances. The Court's judgment in the companion case of "Doe v. Bolton " held a less restrictive Georgia law to be similarly unconstitutional. Both decisions were based on theright to privacy enunciated in "Griswold v. Connecticut ", and remain the primary basis for the constitutional right to abortion in the United States. "Roe" caused an immediate uproar, and Blackmun's opinion made him a target for criticism by opponents of abortion, receiving voluminous negative mail and death threats over the case.Blackmun extended First Amendment protection to commercial speech in

Bigelow v. Commonwealth of Virginia , a case where the Supreme Court overturned the conviction of an editor who ran an advertisement for an abortion referral service.Blackmun became a passionate advocate for abortion rights, often delivering speeches and lectures promoting "Roe v. Wade" as essential to women's equality and criticizing "Roe"'s critics. On the bench, he always voted to strike down laws interfering with women receiving abortions.Fact|date=August 2008

Defending abortion, in "

Thornburgh v. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists " Blackmun wrote: "Few decisions are more personal and intimate, more properly private, or more basic to individual dignity and autonomy, than a woman's decision - with the guidance of her physician and within the limits specified in "Roe" - whether to end her pregnancy. A woman's right to make that choice freely is fundamental..." [Greenhouse, Linda. Becoming Justice Blackmun. Times Books. 2005. Page 185.]Blackmun filed emotional separate opinions in 1989's "

Webster v. Reproductive Health Services " and 1992's "Planned Parenthood v. Casey ", warning that Roe was in jeopardy: "I am 83 years old. I cannot remain on this Court forever, and when I do step down, the confirmation process for my successor well may focus on the issue before us today. That, I regret, may be exactly where the choice between the two worlds will be made."Transition to the left

The controversial decision had a profound effect on him, and afterwards, he gradually began to drift away from the influence of

Chief Justice Warren Burger andAssociate Justice William Rehnquist to increasingly side with liberal JusticeWilliam J. Brennan in finding constitutional protection for unenumerated individual rights. For example, Blackmun wrote a blistering dissent to the Court's opinion in 1986's "Bowers v. Hardwick ", denying constitutional protection to homosexual sodomy (Burger wrote a concurring opinion in "Bowers" in which he said, "To hold that the act of homosexual sodomy is somehow protected as a fundamental right would be to cast aside millennia of moral teaching.") Burger and Blackmun drifted apart, and as the years passed, their lifelong friendship degenerated into a hostile and contentious relationship.From the 1981 term through the 1985 term, Blackmun voted with Justice Brennan 77.6 percent of the time, and with Thurgood Marshall 76.1 percent. [Greenhouse, Linda. Becoming Justice Blackmun. Times Books. 2005. Page 235.] From 1986 to 1990, his rate of agreement with the two most liberal justices was 97.1 percent and 95.8 percent. [Greenhouse, Linda. Becoming Justice Blackmun. Times Books. 2005. Page 235.]

Blackmun's judicial philosophy increasingly seemed guided by "Roe", even in areas where "Roe" was not directly applicable. His concurring opinion in 1981's "

Michael M. v. Superior Court ", a case that upheld statutory rape laws that applied only to men but did not implicate "Roe" or abortion, nonetheless included extensive citation of the Court's recent abortion cases. [ [http://www.law.cornell.edu/supct/html/historics/USSC_CR_0450_0464_ZC1.html BLACKMUN, J., Concurring Opinion in Michael M. v. Superior Court] ]Later years on the bench: Blackmun and the death penalty

Blackmun is widely considered to have moved to the left over the years, but he himself felt that the Court changed around him, growing more conservative with the elevation of

William Rehnquist to Chief Justice and the replacement of the last of the Warren Court justices.Still, Blackmun undoubtedly changed his views on many issues. For example, Blackmun, despite his stated personal 'abhorrence' for the death penalty in "

Furman v. Georgia ", voted to uphold mandatory death penalty statutes at issue in 1976's "Roberts v. Louisiana" and "Woodson v. North Carolina", even though these laws would have automatically imposed the death penalty on anyone found guilty of first-degree murder. But onFebruary 22 ,1994 , less than two months before announcing his retirement, Blackmun announced that he now saw the death penalty as always and in all circumstances unconstitutional by issuing a dissent from the Court's refusal to hear the relatively routine death penalty case of "Callins v. Collins ", declaring that " [f] rom this day forward, I no longer shall tinker with the machinery of death." Subsequently, adopting the practice begun by Justices Brennan and Marshall, he issued in every death penalty case presented to the Court, a brief statement citing and reiterating his "Callins" dissent. AsLinda Greenhouse and others have reported, Blackmun's law clerks prepared what would become the "Callins" dissent well in advance of the case coming before the Court; Blackmun's papers indicate that work began on the dissent in the summer of 1993, and in a memo preserved in Blackmun's papers, the clerk writing the dissent wrote Blackmun that " [t] his is a very personal dissent, and I have struggled to adopt your 'voice' to the best of my ability. I have tried to put myself in your shoes and write a dissent that would reflect the wisdom you have gained, and the frustration you have endured, as a result of twenty years of enforcing the death penalty on this Court." Blackmun and his clerks then sought an appropriate case to serve as a "vehicle for [the] dissent," and settled on "Callins". [http://legalaffairs.org/printerfriendly.msp?id=817] (That the case found the dissent, rather than the more traditional relationship of the dissent relating to the case, is underscored by the opinion's almost total omission of reference to the case it ostensibly addressed: Callins is relegated to a supernumerary in his own appeal, being mentioned but five times in a forty-two paragraph opinion - three times within the first two paragraphs, and twice in footnote 2. [http://supct.law.cornell.edu/supct/html/93-7054.ZA1.html#FNSRC2] ).In his emotional dissent in 1989's "

DeShaney v. Winnebago County ", rejecting the constitutional liability of the state of Wisconsin for four-year-old Joshua DeShaney, who was beaten until brain-damaged by his abusive father, Blackmun famously opined, "Poor Joshua!" In his dissent in 1993's "Herrera v. Collins ", where the Court refused to find a constitutional right for convicted prisoners to introduce new evidence of "actual innocence" for purposes of obtaining federal relief, Blackmun argued in a section joined by no other justice that "The execution of a person who can show that he is innocent comes perilously close to simple murder."Like Justice

Byron White , Blackmun was amenable to grantingcertiorari to most petitions that crossed his desk (indeed, he wrote numerous dissents from denial of cert). At least partially as a result of White and Blackmun's retirements, the number of cases heard each session of the Court declined steeply. In the 1970s and early 1980s, it was not unusual for the Court to decide upwards of 150 cases a term, but by the late 1990s, the Court was typically deciding around 80 cases per term.Women's Rights

After his opinion in "Roe v. Wade", Blackmun was seen more and more as a champion of women's rights. In "

Stanton v. Stanton ", a case striking down a state's discriminatory definitions of adulthood (males reaching it at 21, women at 18), Blackmun wrote: "A child, male or female, is still a child... No longer is the female destined solely for the home and the rearing of the family, and only the male for the marketplace and the world of ideas... If a specified age of minority is required for the boy in order to assure him parental support while he attains his education and training, so, too, is it for the girl." [Greenhouse, Linda. Becoming Justice Blackmun. Times Books. 2005. Page 218.]Post-Supreme Court

Blackmun announced his retirement from the Supreme Court in April 1994, four months before he officially left the bench. By then, he had become the court's most liberal justice. [Greenhouse, Linda. Becoming Justice Blackmun. Times Books. 2005. Page 235.] In his place, President

Bill Clinton nominatedStephen Breyer who was confirmed by the Senate 87-9.On

February 22 ,1999 , Blackmun fell in his home and broke his hip. The next day, he underwent hip replacement surgery at Arlington Hospital inArlington, Virginia , but he never fully recovered. Ten days later, onMarch 4 , he died at 1 a.m. from complications following the procedure. He was buried five days later atArlington National Cemetery . His wife died seven years later onJuly 13 ,2006 , at the age of 95 and was buried next to him.At Blackmun's will, in 2004 (five years after his death) the

Library of Congress released his voluminous files. Blackmun had kept all the documents from every case, notes the Justices passed between themselves, ten percent of the mail he received, and numerous other documents. And after Blackmun announced his retirement from the Court, he recorded a 38-hour oral history with one of his former law clerks,Yale University professorHarold Koh which was also released. In it, he discusses his thoughts on everything from his important Court cases to the Supreme Court piano, though some Supreme Court experts such asDavid Garrow have cast doubt on the accuracy of some of Blackmun's recollections, especially his thoughts on the Court's deliberations on "Roe v. Wade".Based on these papers,

Linda Greenhouse of "The New York Times " wrote "Becoming Justice Blackmun".Blackmun is the only Supreme Court justice to have played one in a motion picture. In 1997, he portrayed Justice

Joseph Story in the Steven Spielberg film "Amistad".References

*Clinton, Bill (2005). "My Life". Vintage. ISBN 1-4000-3003-X.

* [http://www.nndb.com/people/223/000053064/ Harry Blackmun profile, NNDB] .

*Greenhouse, Linda (2005). "Becoming Justice Blackmun". Henry Holt. ISBN 0-8050-8057-0.

*Wrightsman, Lawrence S., and Justin R. La Mort (2005). [http://law.missouri.edu/lawreview/archives/vol70iss4.html Why Do Supreme Court Justices Succeed or Fail? Harry Blackmun as an Example] . "Missouri Law Review" 70.

*Yarbrough, Tinsley. "Harry A. Blackmun: The Outsider Justice". Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195141237.External links

* [http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/angel/procon/deathissue.html Excerpt from Blackmun's "Callins" opinion, and Justice Scalia's response]

* [http://www.npr.org/news/specials/blackmun/ NPR series on Justice Blackmun's Files]

* [http://lcweb2.loc.gov/cocoon/blackmun-public/page.html?FOLDERID=D0901&SERIESID=D09 Transcript: The Justice Harry A. Blackmun Oral History Project]

* [http://aclu.procon.org/viewsource.asp?ID=2193 ProCon.org's Justice Blackmun Bio]References

Persondata

NAME= Blackmun, Harry Andrew

ALTERNATIVE NAMES=

SHORT DESCRIPTION=Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1970 to 1994

DATE OF BIRTH=November 12 ,1908

PLACE OF BIRTH=Nashville ,Illinois

DATE OF DEATH=March 4 ,1999

PLACE OF DEATH=Arlington, Virginia

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.