- Serpent (Bible)

-

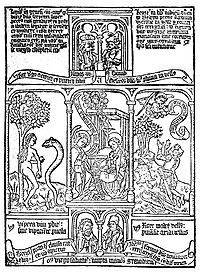

Adam, Eve, and the (female) Serpent at the entrance to Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris. Medieval Christian art often depicted the Edenic Serpent as a woman, thus both emphasizing the Serpent's seductiveness as well as its relationship to Eve.

Adam, Eve, and the (female) Serpent at the entrance to Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris. Medieval Christian art often depicted the Edenic Serpent as a woman, thus both emphasizing the Serpent's seductiveness as well as its relationship to Eve.

Serpent is the term used to translate a variety of words in the Hebrew bible, the most common being Hebrew: נחש, (nahash), the generic word for "snake".

The most famous Biblical serpent is the talking snake in the Garden of Eden who tempts Eve to eat the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge and denies that death will be a result. The Serpent has the ability to speak and to reason, and is identified with the wisdom of this world: "Now the serpent was more subtle than any beast of the field which the Lord God had made" (Genesis 3:1). There is no indication in the Book of Genesis that the Serpent was a deity in its own right, although it is one of only two cases of animals that talk in the Pentateuch (Balaam's donkey being the other).

In Genesis, the Serpent is portrayed as a deceptive creature or trickster, who promotes as good what God had forbidden, and shows particularly cunning in its deception. (cf. Gen. 3:4–5 and 3:22) The New Testament's Book of Revelation identified Genesis' Serpent as Satan and in the process redefined the Hebrew Bible's concept of Satan ("the Adversary", a member of the Heavenly Court acting on behalf of God to test Job's faith), so that Satan/Serpent became a part of a divine plan stretching from Creation to Christ and the Second Coming.[1]

Contents

The serpent as a myth figure in the Near East

The serpent was a widespread figure in the mythology of the Ancient Near East. Archaeologists have uncovered serpent cult objects in Bronze Age strata at several pre-Israelite cities in Canaan: two at Megiddo,[2] one at Gezer,[3] one in the sanctum sanctorum of the Area H temple at Hazor,[4] and two at Shechem.[5] In the surrounding region, a late Bronze Age Hittite shrine in northern Syria contained a bronze statue of a god holding a serpent in one hand and a staff in the other.[6] In sixth-century Babylon, a pair of bronze serpents flanked each of the four doorways of the temple of Esagila.[7] At the Babylonian New Year's festival, the priest was to commission from a woodworker, a metalworker and a goldsmith two images one of which "shall hold in its left hand a snake of cedar, raising its right [hand] to the god Nabu".[8] At the tell of Tepe Gawra, at least seventeen Early Bronze Age Assyrian bronze serpents were recovered.[9] The Sumerian fertility god Ningizzida was sometimes depicted as a serpent with a human head, eventually becoming a god of healing and magic.

Joseph Campbell in his Occidental Mythology speculates that Yahweh is may have originated as a serpent consort of the Earth Mother goddess Asherah. He compares Egyptian worship of Set with Yahwism (the academic term for the religion of Judah prior to the Exilic period), adducing as a parallel as the sacrifice of the red heifer (detailed in Plutarch's Isis and Osiris), as well a parallel between Yahweh and the snake-legged Greek Typhon, whose image appears with the name "Ia", "Iah" or "Yah" on many amulets and charms found among the graves of the Maccabees.[clarification needed]

Hebrew Bible

The generic word for snakes in the Hebrew bible is "nahash" (this is the word used in Genesis 3), although other words are used, including, among others, "sarap" and "tannin."

The serpent of Genesis 3 appears in the Garden of Eden to tempt Eve. God placed Adam in the garden to tend it (Genesis 2:15), but he has warned both Adam and Eve not to eat the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge, "or you will die" (NIV; KJV "lest ye die"; Genesis 3:3). The snake tells Eve that this is untrue, and that if she and the man eat the fruit they will have knowledge and will not die. So Adam and Eve eat the fruit, but the knowledge they gain is loss of child-like innocence, and they are banished from the garden. The snake is punished for its role in their fall by being made to crawl on its belly in the dust, from where it continues to bite the heel of man.

The legged and speaking serpent of Genesis plays the role of trickster, a speaking animal which is not entirely animal and even shares knowledge with God which is hidden from man. As with other trickster-figures, the gift it brings is ambiguous: Adam and Eve gain knowledge, but lose Eden. The choice of a venomous snake for this role seems to arise from Near Eastern traditions associating snakes with danger and death, magic and secret knowledge, rejuvenation, immortality, and sexuality. It is also possible that the association of the snake with the nude goddess in Canaanite iconography lies behind the scene in the divine garden between the snake and naked Eve, "Mother of all life," seemingly a goddess epithet.[10]

Elsewhere in the Hebrew Bible snakes are, by and large, simply snakes. They do, however, carry additional overtones: "sarap" forms the root of "Seraphim," the "tannin" is also a form of dragon-monster, and serpents frequently appear in religious contexts, sometimes as agents of misfortune, sometimes of God. "Nahash," for example, has associated meanings of divination, including the verb-form meaning to practice divination or fortune-telling. During the Exodus, the staffs of Moses and Aaron are turned into serpents, a "nahash" for Moses, a "tannin" for Aaron; Pharaoh's magicians call on their own gods and do likewise, but the serpents of Moses and Aaron eat the serpents of the Egyptians, thus demonstrating the power of Yahweh. In the wilderness Moses constructs a bronze "nahash" (the Nehushtan) against the bite of the "seraphim", the "burning ones"; this is later destroyed as a symbol of idolatry, although in fact it was probably placed in the Temple as a symbol of Yahweh's healing power. The prophet Isaiah sees a vision of "seraphim" in the Temple itself: but these are divine agents, with wings and human faces, and are probably not to be interpreted as serpent-like so much as flame-like.[11]

Apocrypha, Pseudepigrapha, Dead Sea scrolls and Talmud

The first Jewish source to connect the serpent with the devil may be Wisdom of Solomon.[12] The subject is more developed in Apocalypse of Moses (Vita Adae et Evae) where the devil works with the serpent.[13]

Christian interpretation

In traditional Christianity, a connection between the Serpent and Satan is strongly made, and Genesis 3:14-15 where God curses the serpent, is seen in that light: "And the LORD God said unto the serpent, Because thou hast done this, thou art cursed above all cattle, and above every beast of the field; upon thy belly shalt thou go, and dust shalt thou eat all the days of thy life / And I will put enmity between thee and the woman, and between thy seed and her seed; it shall bruise thy head, and thou shalt bruise his heel" (KJV).

In the narratives of the temptations of Christ the devil cites Psalm 91:11-12 “For he will command his angels concerning you, to guard you in all your ways." but breaks off before the concluding promise in verse 13 to "tread upon the serpents and scorpions and vanquish the lion and dragon."[14]

In the Gospel of Matthew 3:7, John the Baptist calls the Pharisees and Saducees visiting him a "brood of vipers". Later in Matthew 23:33, Jesus himself uses this imagery, observing: "Ye serpents, ye generation of vipers, how can ye escape the damnation of Gehenna?" ("Hell" is the usual translation of Jesus' word Gehenna.)

Although in the minority, there are at least a couple of passages in the New Testament that do not present the snake with negative connotation. When sending out the Twelve Apostles, Jesus exhorted them "Behold, I send you forth as sheep in the midst of wolves: be ye therefore wise as serpents, and harmless as doves" (Matthew 10:16).

Jesus made a comparison between himself and the setting up of the snake on the hill in the desert by Moses:

- And as Moses lifted up the serpent in the wilderness, even so must the Son of man be lifted up: That whosoever believeth in him should not perish, but have eternal life (John 3:14-15).

In this comparison Jesus was not so much connecting himself to the serpent, but showing the analogy of his being a divinely provided object of faith, through which God would provide salvation, just as God provided healing to those who looked in faith to the brass serpent.

The other most significant reference to the serpent in the New Testament occurs in Revelation 20:2, where the identity of the serpent in Genesis is made explicit:

- "The great dragon was hurled down -- that ancient serpent called the devil, or Satan, who leads the whole world astray..."

Ivory of Christ treading on the beasts from Genoels-Elderen, with four beasts; the basilisk was sometimes depicted as a bird with a long smooth tail.[15]

A further Old Testament passage taken by Christians to identify a serpent with Satan is Psalm 91 (90):13:[16] "super aspidem et basiliscum calcabis conculcabis leonem et draconem" in the Latin Vulgate, literally "The asp and the basilisk you will trample under foot/you will tread on the lion and the dragon", translated in the King James Version as: Thou shalt tread upon the lion and adder: the young lion and the dragon shalt thou trample under feet".[17] This was interpreted as a reference to Christ defeating and triumphing over Satan. The passage led to the Late Antique and Early Medieval iconography of Christ treading on the beasts, in which sometimes two beasts are shown, usually the lion and snake or dragon, and sometimes four, which are normally the lion, dragon, asp (snake) and basilisk (which was depicted with varying characteristics) of the Vulgate. All represented the devil, as explained by Cassiodorus and Bede in their commentaries on Psalm 91.[18] The serpent is often shown curled round the foot of the cross in depictions of the Crucifixion of Jesus from Carolingian art until about the 13th century; often it is shown as dead. The Crucifixion was regarded as the fulfillment of God's curse on the Serpent in Genesis 3:15. Sometimes it is pierced by the cross and in one ivory is biting Christ's heel, as in the curse.[19]

Following the imagery of chapter 12 of the Book of Revelation, Bernard of Clairvaux had called Mary the "conqueror of dragons", and she was long to be shown crushing a snake underfoot, also a reference to her title as the "New Eve"[20]

A limited modern Christian association of religion with snakes is the snake handling ritual practiced in a small number of churches in the U.S., usually characterized as rural and Pentecostal. Practitioners quote the Bible to support the practice, especially the closing verses of the Gospel according to Mark:

- "Behold, I give unto you power to tread on serpents and scorpions, and over all the power of the enemy: and nothing shall by any means hurt you." (Luke 10:19)

- "And these signs shall follow them that believe: In my name shall they cast out devils; they shall speak with new tongues. They shall take up serpents; and if they drink any deadly thing, it shall not hurt them; they shall lay hands on the sick, and they shall recover." (Mark 16:17-18)

Serpent as a figurative account or literal animal

A smaller number of Christian interpreters have considered the serpent as a figurative account or literal animal. Voltaire, drawing on Socinian influences, wrote: "It was so decidedly a real serpent, that all its species, which had before walked on their feet, were condemned to crawl on their bellies. No serpent, no animal of any kind, is called Satan, or Belzebub, or devil, in the Pentateuch."[21]

20th Century scholars such as W. O. E. Oesterley (1921) were cognisant of the differences between the role of the Edenic serpent in the Hebrew Bible and any connection with "ancient serpent" in the New Testament.[22] Modern historiographers of Satan such as Henry Ansgar Kelly (2006) and Wray and Mobley (2007) speak of the "evolution of Satan",[23] or "development of Satan".[24]

See also

- Serpent (symbolism)

- Satan; Devil; Lucifer

- Fall of Man

- Temptation

- Nehushtan

- Draconcopedes

- Mark 16

- Church of God with Signs Following

- Ophites

References

- ^ Harris, Stephen L., Understanding the Bible. Palo Alto: Mayfield. 1985.

- ^ Gordon Loud, Megiddo II: Plates plate 240: 1, 4, from Stratum X (dated by Loud 1650–1550 BC) and Statum VIIB (dated 1250-1150 BC), noted by Karen Randolph Joines, "The Bronze Serpent in the Israelite Cult" Journal of Biblical Literature 87.3 (September 1968:245-256) p. 245 note 2.

- ^ R.A.S. Macalister, Gezer II, p. 399, fig. 488, noted by Joiner 1968:245 note 3, from the high place area, dated Late Bronze Age.

- ^ Yigael Yadin et al. Hazor III-IV: Plates, pl. 339, 5, 6, dated Late Bronze Age II (Yadiin to Joiner, in Joiner 1968:245 note 4).

- ^ Callaway and Toombs to Joiner (Joiner 1968:246 note 5).

- ^ Maurice Viera, Hittite Art (London, 1955) fig. 114.

- ^ Leonard W. King, A History of Babylon, p. 72.

- ^ Pritchard ANET, 331, noted in Joines 1968:246 and note 8.

- ^ E.A. Speiser, Excavations at Tepe Gawra: I. Levels I-VIII, p. 114ff., noted in Joines 1968:246 and note 9.

- ^ K. van der Toorn, Bob Becking, Pieter Willem van der Horst (eds), "Dictionary of deities and demons in the Bible", pp.746-7

- ^ K. van der Toorn, Bob Becking, Pieter Willem van der Horst (eds), "Dictionary of deities and demons in the Bible", pp.744-6

- ^ CTM.: Volume 43 1972 The Wisdom of Solomon deserves to be remembered for the fact that it is the first tradition to identify the serpent of Gen. 3 with the devil: "Through the devil's envy death entered the world" (2:24).

- ^ The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha: Expansions of the "Old ... James H. Charlesworth - 1985 "He seeks to destroy men's souls (Vita 17:1) by disguising himself as an angel of light (Vita 9:1, 3; 12:1; ApMos 17:1) to put into men "his evil poison, which is his covetousness" (epithymia, ..."

- ^ Whittaker, H.A. Studies in the Gospels "Matthew 4" Biblia, Cannock 1996

- ^ A clearer image of this depiction by Wenceslas Hollar is here

- ^ Psalm 91 in the Hebrew/Protestant numbering, 90 in the Greek/Catholic liturgical sequence - see Psalms#Numbering

- ^ Other modern versions, such as the New International Version have a "cobra" for the basilisk, which may be closest to the Hebrew "pethen".Biblelexicon

- ^ Hilmo, Maidie. Medieval images, icons, and illustrated English literary texts: from Ruthwell Cross to the Ellesmere Chaucer, Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2004, p. 37, ISBN 0754631788, 780754631781, google books

- ^ Schiller, I, pp. 112–113, and many figures listed there. See also Index.

- ^ Schiller, Gertrud, Iconography of Christian Art, Vol. I, p. 108 & fig. 280, 1971 (English trans from German), Lund Humphries, London, ISBN 853312702

- ^ Voltaire A philosophical dictionary from the French, 1824 ed. p22

- ^ Oesterley Immortality and the Unseen World: a study in Old Testament religion (1921) "... moreover, not only an accuser, but one who tempts to evil. With the further development of Satan as the arch-fiend and head of the powers of darkness we are not concerned here, as this is outside the scope of the Old Testament."

- ^ Kelly Satan: a biography p360 "However, the idea of Zoroastrian influence on the evolution of Satan is in limited favor among scholars today, not least because the satan figure is always subordinate to God in Hebrew and Christian representations, and Angra Mainyu ..."

- ^ Wray, T. J., Mobley The Birth of Satan

Categories:- Adam and Eve

- Deities in the Hebrew Bible

- Talking animals in mythology

- Christian mythology

- Jewish mythology

- New Testament words and phrases

- Legendary serpents

- Seven in the Book of Revelation

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.