- Lepidoptera migration

-

Catopsilia pomona migrate regularly in South India and Himalayas.

Catopsilia pomona migrate regularly in South India and Himalayas.

Lepidoptera migration is a biological phenomenon whereby populations of butterflies or moths migrate over long distances to areas where they cannot settle for long periods of time. The term migratory butterfly or moth does not indicate a taxonomic clade within the Lepidoptera, but is a term that is used for all such species from the various included families that migrate.

Lepidoptera species migrate on all continents except Antarctica; they migrate from or within subtropical and tropical areas. The terms migratory butterfly and migratory moth are location-bound: they are only known as such in the areas where the species cannot establish themselves permanently.

By migrating, Lepidoptera species can avoid unfavorable circumstances, including weather, food shortage, or over-population. Like birds, there are Lepidoptera species of which all individuals migrate, but there are also species of which only a subgroup of the individuals migrate.

The most famous Lepidopteran migration is that of the Monarch butterfly which migrates from southern Canada to wintering sites in central Mexico. In late winter/early spring, the adult monarchs leave the Transvolcanic mountain range in Mexico for a more northern climate. Mating occurs and the females begin seeking out milkweed to lay their eggs, usually first in northern Mexico and southern Texas. The caterpillars hatch and develop into adults that move north, where more offspring can go as far as Central Canada until next migratory cycle.

The Danaids in South India are also prominent migrators, between Eastern Ghats and Western Ghats. Three species will be involved in this, namely Tirumala septentrionis, Euploea core, and Euploea sylvester. Sometimes they are joined by Lemon Pansy (Junonia lemonias), Common Emigrant (Catopsilia pomona), Tawny coster (Acraea terpsicore) and Blue Tiger (Tirumala limniace).

Butterfly migration happens regularly in the foot hills of Himalayas. Due to lack of continuous study in this area, we don't have substantial information.

Contents

Definition

Migration in Lepidoptera refers to the act of moving from one place to another in a manner that is seasonally determined and predictable.[1] There is no unambiguous definition of migratory butterfly or migratory moth, and this also applies to proposals to divide them into classes.[2] Migration takes place so that organisms can avoid unfavourable environmental conditions that limit breeding.[1]

Migration means different things to behavioral scientists and ecologists. The former emphasize the act of moving whereas the latter discriminate between whether the movement has been ecologically significant or not. Migration may be viewed as "a behavioural process with ecological consequences".[1]

Migration in Lepidoptera takes place in two of the three modes of migration identified by Johnson (Johnson, 1969). In the first mode (also Johnson's first), the Lepidoptera move in one direction in their short life-span and do not return. An example is the pierid butterfly, Ascia monuste, which breeds in Florida but sometimes migrates along the coast up to 160 kilometers to breed in more suitable areas.[1]

In the second mode (Johnson's third), migration takes place to a place of hibernation or aestivation where they undergo diapause and the same generation survives to return. The classic example is that of the nymphalid Monarch butterfly (Danuas plexippus).[1]

The term migration is sometimes also applied to species which move over a vast area on their own strength, but remain within their known habitat, although these are mostly referred to as strays. A well-known example of this is the Large White. This species moves in great numbers, but only to areas where they can remain permanently.

In practice, the terms stray and migratory butterfly or moth overlap; there are species that can survive in a certain area, but in too small numbers to maintain the species in that area permanently. On the other hand, there are species that form a population for more than two years, but are still considered strays. Only when a species has a permanent population in an area for ten years, it is referred to as native.

To add to the confusion, the term stray is also used for migratory species that are not recorded each year, but from time to time. Species that have been recorded very few times are referred to as vagrants.

Adventive

Species that are recorded in unexpected areas (adventive species) are not considered to be migratory species, because these did not leave their habitat on their own strength. Examples are species that are imported as egg or caterpillar alongside of their host plants or individuals that were reared by a collector but have escaped. An example of an introduced species is Galleria mellonella, which is found all over the world, because it is reared as food for captive birds and reptiles. At times it is difficult to decide if a species is adventive or migratory. Migratory species like Chrysodeixis chalcites and Helicoverpa armigera would be able to reach Western Europe on their own, but are also common in greenhouses.

Seasonal migration

Australian species Agrotis infusa spends the summer as an imago in the Australian Alps, and is sometimes found in buildings in large numbers.

Australian species Agrotis infusa spends the summer as an imago in the Australian Alps, and is sometimes found in buildings in large numbers.

Lepidoptera migration is often seasonal. With species of which all individuals migrate, the population moves between areas in the summer and winter season or the dry and wet season.

For species of which only part of the population migrates, seasonal migration is hard to determine. They can maintain themselves in part of their habitat but also reach areas where they cannot establish a permanent population. They only live there in the season that is most favorable for the species. Some of the species have the habit of returning to their permanent residence at the end of the season.

Difference with bird migration

An important difference with bird migration is that an individual butterfly or moth usually migrates in one direction, while birds migrate back and forth multiple times within their lifespan. This is due to the short lifespan as an imago. Species that migrate back and forth, usually do so in different generations. There are however, some exceptions:

- The famous migration of the Monarch butterfly in North America. This species migrates back and forth in one generation, though it completes only part of the journey in both directions in that generation. No individual completes the entire journey which is spread over a number of generations. The imago of the last summer generation is born in North America, migrates to Mexico, Florida, or California and stays there for the winter. After the winter it migrates back to the north to reproduce. In a couple of generations, the monarch migrates north to Canada.

- The migration of Agrotis infusa in Australia. This species migrates from south-eastern Australia to the Australian Alps in the summer to avoid the heat. After the summer it returns to reproduce.

Flight behaviour

The small Diamondback moth is a migratory species which can be found at altitudes of a 100 meters. It is capable of covering over 3,000 kilometers.

The small Diamondback moth is a migratory species which can be found at altitudes of a 100 meters. It is capable of covering over 3,000 kilometers.

Migratory Lepidoptera are, in most cases, excellent flyers. Species like the Vanessa atalanta are capable of managing a fierce headwind. In case of headwind, they usually fly low and are more goal-oriented.[3] During migration, some species can be found on high altitudes, ranging to up to two kilometers [4][5] This is especially noteworthy for day-flying species like Vanessa atalanta, since the temperatures on these altitudes are low and day-flying species depend on the outside temperature to stay warm. It is thought that Vanessa atalanta produces enough body warmth during flight since it has also been recorded migrating at night.

In the case of transcontinental migration where distances are large, the flying speed of the butterfly ( of the order of 3 metres per second or less) is inadequate for timely completion of journey. The migration is carried out by relying on heavy winds; a persistent wind speed of 10 metres per second being able to provide a displacement of 300 to 400 kilometers in a single day.[6] For example, the Painted Lady (Vanessa cardui) migrates from Africa to Spain aided by head winds.[7]

That the migratory species are good flyers, is not the same as saying they are robust flyers. The small Diamondback moth is also a migratory species that migrates 3,000 kilometers and can be found up to altitudes of 100 meters or more.[8][9]

To be able to migrate over long distances, species must be able to navigate. There are several ways they do this.

Landscape: Lepidoptera use coastal lines, mountains, but also man-made roads to orient themselves. Above sea it has been observed that the flight direction is much more accurate if the landscape on the coast is still visible.[3]

Celestial navigation: Butterflies are known to be capable of navigation with the help of the sun. They can also navigate by using polarized light. The polarization of the sun's light changes with the angle of the rays, hence they can also navigate with cloudy weather. There are indications that they can even make corrections depending on the time on a day. Diamondback moths are known to fly in a straight trajectory which is not dependent on the angle of the sun's rays.[10] Tests have been performed to interfere with the biological clock of certain species by keeping them in the dark and then observing if they would choose for other flight paths. The conclusion was that some species did, and others did not.[11] Research on monarchs demonstrates that with removal of antennae, the location of the circadian clock, individuals do not localize in any one direction during flight as they do with antennae intact. [12] Night flyers cannot use sun light for navigation. Most of these species rely on the moon and stars instead.

Earth’s magnetic field: A number of moths use the Earth's magnetic field to navigate, as a study of the stray Heart and Dart[13] suggests. Another study, this time of the migratory behaviour of the Silver Y, showed that this species, even at high altitudes, can correct its course with changing winds, and prefers flying with favourable winds, which suggests a great sense of direction.[14] Aphrissa statira in Panama loses its navigational capacity when exposed to a magnetic field, suggesting it uses the Earth’s magnetic field.[15]

Areas where migratory butterflies and moths can be found

Migratory Lepidoptera can be found on all continents, migrating within or from the Tropics and Subtropics. North, they can be found up to Spitsbergen, above the Arctic Circle.[9] Some migratory Lepidoptera have spread over most of the world. Some of these are pest insects, such as the diamondback moth, Helicoverpa armigera, and Trichoplusia ni.

Examples of migratory Lepidoptera

Some examples of Migratory Lepidoptera are:

- In the Indian subcontinent, migrating Lepidoptera are common just before the monsoon season. Over 250 species are known to migrate during this period.[16][17]

- On Madagascar, Chrysiridia rhipheus migrates between populations of four plant species from the Omphalea genus, the host plant of this species. The three western Omphalea species live in dry coniferous forests, the eastern species is found in the rainforest and is the only species that is green year round.[18]

- Rhodometra sacraria is normally found in Africa, large parts of Asia and Southern Europe. At times, it migrates north and can reach central and northern Europe.

- Vanessa cardui is found all over the world, except South America, on altitudes of up to 3,000 meters above sea level. Its home, however, are subtropical steppe areas.

- Several South and Central American species of Uraniidae display a great peak in migratory behavior in certain years. In the years with a great number of migrating individuals, there are “population explosions”. Individuals migrate to the south and east. There is no real re-migration to speak off. These moths feed on Omphalea species. These can be found in scattered populations all across South and Central America, but only part of the areas where they are found are a permanent habitat for these moths. Research suggests that the cause of the migration peak is an increase in toxicity when much of a single plant is eaten and decreasing toxicity when only small amounts of a certain plant are eaten.[19]

- The migration of Euploea core, Euploea sylvester and Tirumala septentrionis between Western Ghats and Eastern Ghats in India covering up to 350 to 400 km. This migration happens twice a year. The most probable reasons seem to be the Monsoons, lack of diapause and host plants, nectar and alkaloidal resource availability.

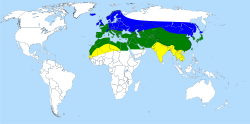

Example species: Macroglossum stellatarum

Macroglossum stellatarum is a moth that is recorded in the subtropical part of the Palearctic ecozone year round. In summer, the species migrate north up to Scandinavia and Iceland. In winter it migrates further south, deeper into Africa and to the Indian subcontinent.

In the Netherlands and Belgium, there are 100 to 200 records per year in an average year. In warm summers however, like the years 2005 and 2006, several thousand are recorded.[20] In mild winters, small numbers can survive this far north, but these numbers are insufficient to call it a real population.[2]

Causes

Usually, butterflies and moths migrate to escape from potentially harmful circumstances. Examples of this are a shortage of proper food plants, an unfavorable climate, like cold or extreme rain or overpopulation.

Migration and evolution

Death's Head Moth (Acherontia atropos) females are significantly less fertile or not fertile at all in the Netherlands.

Death's Head Moth (Acherontia atropos) females are significantly less fertile or not fertile at all in the Netherlands.

A phenomenon like migration is an evolutionary development. By migrating, the species has survived the process of natural selection. There are a number of advantages and disadvantages to migration.

Positive effects for the species

There are positive effects for all Lepidoptera species when migrating over even small distances. It ensures sufficient genetic mixing, which in turn ensures there is no inbreeding. When the displacement takes place over longer distances, this can also lead to the discovery of new suitable habitats, making the species less vulnerable.

Furthermore, displacement over long distances makes it possible to escape from unfavorable circumstances like drought or cold. This makes migration a suitable alternative for diapause. After the negative circumstances have passed, members of the species return to their place of origin.

There are also migratory species that move over long distances, without any recorded re-migration, like several "Sphingidae" species.[2] Some individuals possibly return to their original habitat, but these are only small numbers. The advantages of migration are not all that clear for these species. Researchers think the causes are the food plants of these species, which are mainly herbaceous plants. These plants are more vulnerable for external influences, like drought, in comparison with shrubs or trees. To tackle this problem, a possible solution is migration, which has the additional benefit for the species also escaping from these negative external influences. The fact that many of the migrating individuals find themselves in areas where they cannot survive permanently is apparently of less significance. Furthermore, even a small number of re-migrating individuals can ensure the re-emerging of a population in their original habitat.[19]

Negative effects for the species

Migration has some negative effects on a species. The migration itself costs a lot of energy and is not without risk. During the trip, many individuals die and not all survivors find a suitable habitat. On the outskirts of suitable habitat, fertility can decrease. Acherontia atropos females that are born in temperate areas are significantly less fertile, or not fertile at all.[2]

Reproduction in favorable areas must thus be very high, to shift the balance in favor of migration.

Recording

Butterflies (and to a lesser extent moths) migrating in large numbers are a noteworthy sight, which is easily to observe and track. There are several historic records about migrating butterflies. There are records dating back to 1100 about migrating butterflies (probably a Pieris species) from Bavaria to the Duchy of Saxony and from 1248 about the migration of yellow butterflies in Japan.

When flying at high altitudes, spotting migrating butterflies or moths can be hard. Low flying species are easily spotted or caught using a light trap. When individuals fly too high for these methods, air balloons equipped with nets are used at times. Alternatively, radar is used to monitor migration.[8]

Another registration technique, is marking the wings with tiny stickers, a technique comparable with Bird ringing. This technique has not proven to be very successful though.[3] Advances in technology might make it possible to equip individuals with micro transmitters in the future.

Registration

Both The Netherlands and Belgium have a register of recorded migratory species. In the Netherlands, registration (Trekvlinderregistratie Nederland) started in 1940 and is the world's oldest project in this field.,[21] in Belgium, the registration is called Belgisch Trekvlinder Onderzoek.

Migration and climate change

It seems that global warming has caused an increase of migratory butterflies and moths that reach north-western countries like the Netherlands, Belgium and the United Kingdom. Research in the United Kingdom confirms that an increasing number of migrants reach the country. Because one would expect that migratory species can adapt to new circumstances quite well, the researches warn for new species that can have a negative impact on native species and possible damage to both health (species like the Oak Processionary) and agriculture.[22]

Footnotes

- ^ a b c d e Scoble, MJ. (1995) "Migration" in The Lepidoptera: form, function and diversity. 68-71. Previewed in Google Books [1] on 09 Oct 2009.

- ^ a b c d Meerman, J.C. (1987) "Dutch Sphingidae" Wet. meded. KNNV 180.

- ^ a b c J. Blab, T. Ruckstuhl, T. Esche en R. Holzberger (1989) Actie voor Vlinders, zo kunnen we ze redden, Weert: M&P.

- ^ Gibo, D.L. (1981). "Altitudes attained by migrating monarch butterflies, Danaus p. plexipus (Lepidoptera: Danaidae), as reported by glider pilots". Canadian Journal of Zoology 59 (3): 571–572. doi:10.1139/z81-084.

- ^ Mikkola, K. (2003). "The Red Admiral butterfly (Vanessa atalanta, Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae) is a true seasonal migrant: an evolutionary puzzle resolved?". European Journal of Entomology 100 (4): 625–626. http://www.eje.cz/pdfarticles/253/eje_100_4_625_Mikkola.pdf.

- ^ Drake, V.A.; Gatehouse, A.G. (1995). Insect migration: tracking resources through space and time. Cambridge University Press. p. 3. ISBN 9780521440004. http://books.google.co.in/books?id=z2fMLTS1AVcC. Retrieved 6 May 2010.

- ^ Stefanescu, C.; Alarcón, Marta; Àvila, A. (2007). "Migration of the painted lady butterfly, Vanessa cardui, to north-eastern Spain is aided by African wind currents". Journal of Animal Ecology 67 (5): 888–898. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2656.2007.01262.x. http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/journal/117960308/abstract?CRETRY=1&SRETRY=0.

- ^ a b Chapman, J.W.; Reynolds, DON R.; Smith, A.D. (2003). "Vertical-Looking Radar, A New Tool for Monitoring High-Altitude Insect Migration". BioScience 53 (5): 503–511. doi:10.1641/0006-3568(2003)053[0503:VRANTF]2.0.CO;2. http://www.rothamsted.ac.uk/insect-survey/documents/Vertical-Looking%20Radar.pdf.

- ^ a b Yau I-Chu (1986) "The Migration of Diamondback Moth" in: Diamondback Moth Management, Proceedings of the First International Workshop, Tainan, Taiwan, 11–14 March 1985. Shanhua: The Asian Vegetable Research and Development Center. Inhoud.

- ^ Scott, J.A. (1992). "Direction Of Spring Migration Of Vanessa cardui (Nymphalidae) In Colorado". Journal of Research on the Lepidoptera 31 (1–2): 16–23. Archived from the original on 2006-09-06. http://web.archive.org/web/20060906201226/http://www.doylegroup.harvard.edu/~carlo/JRL/31/PDF/31-016.pdf.

- ^ Oliveira, E.G.; Dudley; Srygley, R.B. (1996). "Evidence for the use of a solar compass by neotropical migratory butterflies". Bulletin of the Ecological Society of America 775: 332.

- ^ Merlin, C.; Gegear, R.J.; Reppert, S.M. (2009). "Antennal circadian clocks coordinate sun compass orientation in migratory monarch butterflies". Science 325 (5948): 1700–4. doi:10.1126/science.1176221. PMC 2754321. PMID 19779201. http://reppertlab.org/media/files/publications_files/scienceantennapaper.pdf.

- ^ Baker, R.R. (1987). "Integrated use of moon and magnetic compasses by the heart-and-dart moth, Agrotis exclamationis". Animal Behaviour 35: 94–101. doi:10.1016/S0003-3472(87)80214-2.

- ^ Scientists make compass discovery in migrating moths, University of Greenwich.

- ^ Srygley, R; Dudley, R; Oliveira, E; Riveros, A (2006). "Experimental evidence for a magnetic sense in Neotropical migrating butterflies (Lepidoptera: Pieridae)" (PDF). Animal Behaviour 71: 183–191. doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2005.04.013. http://users.ox.ac.uk/~zool0206/AnimBeh06.pdf.

- ^ C.B. Williams (1930) The Migration of Butterflies Oliver & Boyd: Edinburgh.

- ^ Senthilmurugan, B. (2005). "Mukurthi National Park: A migratory route for butterflies". J. Bombay. Nat. Hist. Soc. 102 (2): 241–242.

- ^ Smith, N. (1991). "Foodplants of the Uraniinae (Uraniidae) and their Systematic, Evolutionary and Ecological Significance". The Journal of the Lepidopterists' Society 45 (4): 296–347. http://research.yale.edu/peabody/jls/pdfs/1990s/1991/1991-45(4)296-Lees.pdf.

- ^ a b Smith, N.G. (1983). "Host Plant Toxicity and Migration in the Dayflying Moth Urania". Florida Entomologist 66 (1): 76–87. doi:10.2307/3494552. JSTOR 3494552. http://fulltext10.fcla.edu/DLData/SN/SN00154040/0066_001/98p0321w.pdf.

- ^ Vlindernet. Retrieved on 2008-08-26.

- ^ see Trekvlinderregistratie Nederland

- ^ Sparks, T.H.; Dennis, R.L.H.; Croxton, P.J.; Cade, M. (2007). "Increased migration of Lepidoptera linked to climate change". European Journal of Entomology 104 (1): 139–143. http://www.eje.cz/pdfarticles/1207/eje_104_1_139_Sparks.pdf.

References

- Bos, F. et al. (2006) De Dagvlinders van Nederland (Nederlandse Fauna, deel 7), Utrecht en Leiden, p. 13.

- Drake,V.A. and Gatehouse,A.G. (1995), Insect Migration: Tracking Resources Through Space and Time, Camebridge University Press. (ISBN 0521440009). Google Books

- Lempke,B.J. De Nederlandse Trekvlinders, Zutphen (KNNV-Thieme), 1956. Tweede druk in 1972.

- Kuchlein,J.H. and de Vos,R. (1999). Geannoteerde Naamlijst van de Nederlandse Vlinders, Leiden (Backhuys).

Swarming Swarm algorithms - Agent-based models

- Ant colony optimization

- Ant robotics

- Artificial Ants

- Bees algorithm

- Bee colony optimization

- Boids

- Crowd simulation

- Firefly algorithm

- Glowworm swarm optimization

- Particle swarm optimization

- Self-propelled particles

- Swarm intelligence

- Swarm (simulation)

Biological swarming - Agent-based model in biology

- Bait ball

- Collective animal behavior

- Feeding frenzy

- Flock

- Flocking

- Herd

- Herd behavior

- Mixed-species foraging flock

- Mobbing behavior

- Pack hunter

- Patterns of self-organization in ants

- Sardine run

- Shoaling and schooling

- Sort sol

- Swarming behaviour

- Swarming (honey bee)

- Swarming motility

Animal migration - Animal migration

- Bird migration

- Bird migration flyways

- Diel vertical migration

- Fish migration

- Homing (biology)

- Insect migration

- Lessepsian migration

- Lepidoptera migration

- Reverse migration

- Tracking animal migration

Swarm robotics Related topics Categories:

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.