- Magellan (spacecraft)

-

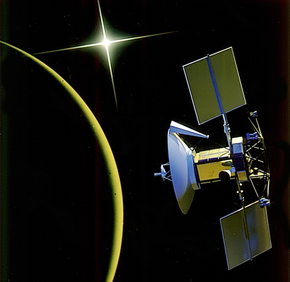

Magellan

Artist's depiction of Magellan at VenusOperator NASA / JPL Major contractors Martin Marietta / Hughes Aircraft Mission type Orbiter Satellite of Venus Orbital insertion date 1990-08-10 17:00:00 UTC Launch date 1989-05-04 18:47:00 UTC

(22 years, 6 months and 10 days ago)Launch vehicle Space Shuttle Atlantis (STS-30)

Inertial Upper StageLaunch site Launch Complex 39B,

Kennedy Space CenterMission duration Aug 10, 1990 - Oct 12, 1994

(4 years, 2 months, 3 days)

(deorbited)COSPAR ID 1989-033B Homepage Home page

Magellan Mission to Venus -NSSDC archiveMass 1,035 kg (2,280 lb) Power 1029 W

(Solar array / NiCad)The Magellan spacecraft, also referred to as the Venus Radar Mapper, was a 1,035-kilogram robotic space probe launched by NASA on May 4, 1989, to map the surface of Venus using Synthetic Aperture Radar and measure the planetary gravity. It was the first interplanetary mission to be launched from the Space Shuttle, the first to use an inertial upper stage booster and was the first spacecraft to test aerobraking as a method for circularizing an orbit. Magellan was the fourth successful, NASA funded mission to Venus and ended an eleven year U.S. interplanetary exploration hiatus.

Contents

Mission background

History

Beginning in the late 1970s, scientists pushed for a radar mapping mission to Venus. First seeking to construct a spacecraft titled, Venus Orbiter Imaging Radar, it became obvious the mission would be outside the limits of the budgetary constraints during the following years and was subsequently canceled in 1982. Recommended by the Solar System Exploration Committee, a stripped down mission proposal was resubmitted and accepted as the Venus Radar Mapper in 1983. The proposal included a limited focus and a single primary scientific instrument. In 1985, the mission was renamed Magellan, after the sixteenth-century Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan, for his exploration, mapping and circumnavigation of the Earth, a goal this mission would have for Venus.[1][2][3]D:] <3

The objectives of the mission included[4]:

- Obtain near-global radar images of Venus' surface with a resolution equivalent to optical imaging of 1 km per line pair. (primary)

- Obtain a near-global topographic map with 50 km spatial and 100 m vertical resolution.

- Obtain near-global gravity field data with 700 km resolution and 2–3 milligals accuracy.

- Develop an understanding of the geological structure of the planet, including its density distribution and dynamics.

The spacecraft was designed and built by Martin Marietta and JPL provided mission management for the NASA division. Elizabeth Beyer served as program manager and Joseph Boyce served as lead program scientist for the NASA headquarters; for operations at JPL, Douglas Griffith served as Magellan project manager and R. Stephen Saunders served as lead project scientist.[1]

Spacecraft design

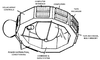

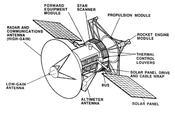

To save costs, Magellan was made of many spare parts from various missions, including the Voyager Program, Galileo, Ulysses and Mariner 9. The spacecraft was built by the Martin Marietta Astronautics Group in Denver, Colorado.[5] The main body of the spacecraft, a spare from the Voyager missions, was a 10-sided aluminum bus, containing the computers, data recorders, and other subsystems. The spacecraft measured 6.4-meters tall and 4.6 meters in diameter. Overall, the spacecraft weighed 1,035-kilograms and carried 2,414-kilograms of propellant for a total mass of 3449-kilograms.[2][6]

Attitude control and propulsion

- The spacecraft was three-axis stabilized with three reaction wheels and twenty-four thrusters with 132.5-kilograms of hydrazine monopropellant onboard. Of the thrusters, eight are aimed aft, providing 444.82-N of thrust for course corrections, control of the spacecraft during the Venus orbital insertion maneuver and large orbit corrections during the mission; four along the side of the spacecraft provide 22.24-N for roll; the smallest twelve provide 0.88-N for minor attitude corrections and offsetting, or "desaturating", the reaction wheels. To perform the Venus orbital insertion maneuver, the spacecraft was equipped with a Star 48 booster containing 2,014-kilograms of solid-propellant. Information regarding the orientation of the spacecraft was provided by a set of gyroscopes and a star scanner.[2][3][6][7]

Communications

- For communications, the spacecraft included a lightweight graphite/aluminum, 3.7-meter high-gain antenna left over from the Voyager Program and a medium-gain antenna spare from the Mariner 9 mission; attached to the high-gain antenna, a low-gain antenna was also included for contingency measures. When communicating with the Deep Space Network, the spacecraft was able to simultaneously receive commands at 1.2-kilobits/second across the S-band and transmit data at 268.8-kilobits/second via X-band.[2][3][6][7]

Power

- Magellan was powered by two square solar arrays, each measuring 2.5-meters across. Together, the arrays supplied 1,200-watts of power at the beginning of the mission. However, over the course of the mission the solar arrays gradually degraded due to frequent, extreme temperature changes. To power the spacecraft while occluded from the Sun, two 30-amp hour, 26-cell, Nickel-Cadmium batteries were included; the batteries recharged as the spacecraft received direct sun light.[2][6]

Computer

- The computing system on the spacecraft, derived from the Galileo mission, included two ATAC-16 computers to control attitude, and four RCA 1802 microprocessors to control the Command and Data Subsystem (CDS). The CDS was able to store commands for up to three days, and to autonomously control the spacecraft if problems were to arise while mission operators weren't in contact with the spacecraft. For storing the commands and recorded data, the spacecraft also included two multitrack digital tape recorders, able to store up to 225-Megabytes until contact with Earth was restored and the tapes were played back.[2][6][7]

Scientific instruments

Radar System (RDRS)

The Radar System functioned in three modes: Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR), Altimetry (ALT), and Radiometry (RAD). The instrument cycled through the three modes while observing the surface geology, topography and temperature of Venus using the 3.7-meter parabolic, high-gain antenna and a small fan-beam antenna, located just to the side. - - In Synthetic Aperture Radar mode, the instrument transmitted several thousand long-wave, 12.6-centimeter microwave pulses every second through the high-gain antenna, while measuring the doppler shift of each hitting the surface.

- - In Altimetry mode, the instrument interleaved pulses with SAR, and operating similarly with the altimetric antenna, recording information regarding the elevation of the surface on Venus.

- - In Radiometry mode, the high-gain antenna was used to record microwave radiothermal emissions from Venus. This data was used to characterize the surface temperature.

The data was collected at 750 kilobits/second to the tape recorder and later transmitted to earth to be processed into usable images, by the Radar Data Processing Subsystem (RDPS), a collection of ground computers operated by JPL.

- Principal investigator: Gordon Pettengill / MIT

- Data: PDS/IN catalog, PDS/GSN archive

Aperture synthesis

Thick and opaque, the atmosphere of Venus required a method beyond optical survey, to map the surface of the planet. The resolution of conventional radar depends entirely on the size of the antenna, which is greatly restricted by costs, physical constraints by launch vehicles and the complexity of maneuvering a large apparatus to provide high resolution data. The Magellan spacecraft avoided this problem by using a method known as aperture synthesis, where a large antenna is imitated by processing the information gathered, by ground computers.[8][12]

The Magellan high-gain antenna, oriented 28°–78° to the right or left of nadir, emitted thousands of microwave pulses that passed through the clouds and to the surface of Venus, illuminating a swath of land. The Radar System then recorded the brightness of each pulse as it reflected back off the side surfaces of rocks, cliffs, volcanoes and other geologic features, as a form of backscatter. To increase the imaging resolution, Magellan recorded a series of data bursts for a particular location during multiple instances called, "looks". Each "look" slightly overlapped the previous, returning slightly different information for the same location, as the spacecraft moved in orbit. After transmitting the data back to Earth, Doppler modeling was used to take the overlapping "looks" and combine them into a continuous, high resolution image of the surface.[8][12][13]

Images of the spacecraft Annotated diagram of Magellan.Magellan during pre-flight checkout.Mission profile

Timeline of travel Date Event 1989-05-04Space shuttle vehicle launched at 18:46:59 UTC. 1989-05-05Spacecraft deployed from shuttle at 01:06:00 UTC. 1990-08-01Begin Venus primary mission operations Time Event 1990-08-01Venus orbital insertion maneuver. 1990-09-15Begin mapping cycle 1 1991-05-15Phase stop 1991-05-16Begin Venus extended mission operations Time Event 1991-05-16Begin mapping cycle 2 1992-01-24Begin mapping cycle 3 1992-09-14Begin mapping cycle 4 1993-05-26Begin testing aerobraking maneuver to place Magellan into an almost circular orbit. 1993-08-16Begin mapping cycle 5 1994-04-16Begin mapping cycle 6 1994-04-16Begin "windmill" experiment 1994-10-12Phase stop 1994-10-13End of mission. Deorbited into Venusian atmosphere. Loss of contact at 10:05:00 UTC. Launch and trajectory

Magellan was launched on May 4, 1989, at 18:46:59 UTC by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration from KSC Launch Complex 39B at the Kennedy Space Center in Florida, aboard Space Shuttle Atlantis during mission STS-30. Once in orbit, an Inertial Upper Stage booster, deployed from the shuttle and launched on May 5, 1989 01:06:00 UTC, sending the spacecraft into a Type IV, heliocentric orbit where it would circle the Sun 1.5 times, before reaching Venus 15 months later on August 10, 1990.[3][6][7]

Originally, Magellan had been scheduled for launch in 1988 with a trajectory lasting six months. However, due to the Space Shuttle Challenger disaster in 1986, several missions, including Galileo and Magellan, were deferred until the shuttle flights resumed September 1988. Intended to be launched with a new, liquid fueled, Centaur-G shuttle deploy-able upper-stage booster, subsequently canceled after the Challenger disaster, Magellan had to be modified to attach to a less powerful solid-fueled, Inertial Upper Stage. The next best opportunity for launch would occur in October 1989.[3][6]

Further complicating the launch however, was the upcoming Galileo mission to Jupiter, which included a flyby of Venus. Intended for launch in 1986, the pressures to ensure a launch for Galileo in 1989, mixed with a short launch-window necessitating a mid-October launch, resulted in replanning the Magellan mission. Weary of rapid shuttle launches, the decision was made to launch Magellan in May, and into an orbit that would require 1 year and 3 months before encountering Venus.[3][6]

Trajectory of Magellan to Venus.Orbital encounter of Venus

VideoMain article: Exploration of Venus

VideoMain article: Exploration of VenusOn August 1, 1990, Magellan encountered Venus and began the orbital insertion maneuver which placed the spacecraft into a 3 hour and 9 minute, elliptical orbit which brought the spacecraft 295-kilometers from the surface at approximately 10° North during apoapsis and out to 7762-kilometers during periapsis.[6][7]

During each orbit, the spacecraft would capture radar data while the spacecraft was nearest to the surface and then transmit it back to Earth as it moved away from Venus. This maneuver required extensive use of the reaction wheels to continuously rotate the spacecraft as it imaged the surface for 37-minutes and as it pointed toward Earth for 2 hours. The primary mission intended for the spacecraft to return images of at least 70% of the surface during one Venusian day, which lasts 243 Earth days as the planet slowly spins. To avoid overly redundant data at the highest and lowest latitudes Magellan alternated between a Northern-swath, a region designated as 90° north latitude to 54° south latitude, and a Southern-swath, designated as 76° north latitude to 68° south latitude. However, due to apoapsis being 10° north of the equatorial line, imaging the South Pole region was unlikely to be possible.[6][7]

Mapping cycle 1

- Goal: Complete primary objective.[4]

- September 15, 1990 - May 15, 1991

The primary mission began on September 15, 1990, with the intention to provide a "left-looking" map of 70% of the Venusian surface at a minimum resolution of 1-kilometer/pixel. During cycle 1, the altitude of the spacecraft varied from 2000-kilometers at the north pole, to 290-kilometers near apoapsis. Upon completion during May 15, 1991, having made 1,792 orbits, Magellan had mapped approximately 83.7% of the surface with a resolution between 101 to 250-meters/pixel.[7][15]

Mission extension

Mapping cycle 2

- Goal: Image the south pole region and gaps from Cycle 1.[16]

- May 15, 1991 - January 14 , 1992

Beginning immediately after the end of cycle 1, cycle 2 was intended to provide data for the existing gaps in the map collected during first cycle, including a large portion of the southern hemisphere. To do this, Magellan had to be reoriented with 180°, changing the gathering method to "right-looking". Upon completion during mid-January 1992, cycle 2 provided data for 54.5% of the surface, and combined with the previous cycle, a map containing 96% of the surface could be constructed.[7][15]

Mapping cycle 3

- Goal: Fill remaining gaps and collect stereo imagery.[16]

- January 15, 1992 - September 13, 1992

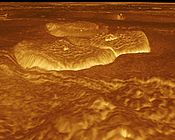

Immediately after cycle 2, cycle 3 began collecting data for stereo imagery on the surface that would later allow the ground team to construct, clear, three-dimensional renderings of the surface. Approximately 21.3% of the surface was imaged in stereo by the end of the cycle on September 13, 1992, increasing the overall coverage of the surface to 98%.[7][15]

Map of the stereo imaging collected by Magellan during cycle 3.Volcanic dome observed from reprojecting stereo data.Mapping cycle 4

- Goal: Measure Venus' gravitational field.[16]

- September 14, 1992 - May 23, 1993

Upon completing cycle 3, Magellan ceased imaging the surface. Instead, beginning mid-September 1992, the Magellan maintained pointing of the high-gain antenna toward Earth where the Deep Space Network began recording a constant stream of telemetry. This constant signal allowed the DSN to collect information on the gravitational field of Venus by monitoring the velocity of the spacecraft. Areas of higher gravitation would slightly increase the velocity of the spacecraft, registering as a Doppler shift in the signal. The space craft completed 1,878 orbits until completion of the cycle on May 23, 1993; a loss of data at the beginning of the cycle necessitated an additional 10 days of gravitational study.[7][15]

Mapping cycle 5

- Goal: Aerobraking to circular orbit and global gravity measurements.[16]

- May 24, 1993 - August 29, 1994

At the end of the fourth cycle in May 1993, the orbit of Magellan was circularized using an unproven technique known as aerobraking. The circularized orbit allowed a much higher resolution of gravimetric data to be acquired when cycle 5 began on August 3, 1993. The spacecraft performed 2,855 orbits and provided high-resolution gravimetric data for 94% of the planet, before the end of the cycle on August 29, 1994.[2][3][7][15]

Aerobraking

- Goal: To enter a circular orbit[16]

- May 24, 1993 - August 2, 1993

- Aerobraking had long been sought as a method for slowing the orbit of interplanetary spacecraft. Previous suggestions included the need for aeroshells that proved too complicated and expensive for most missions. Testing a new approach to the method, a plan was devised to drop the orbit of Magellan into the outer-most region of the Venusian atmosphere. Slight friction on the spacecraft slowed the velocity over a period, slightly longer than two months, bringing the spacecraft into an approximate, circular orbit from 180-kilometers at apoapsis to 540-kilometers at periapsis. The method has since been used extensively on subsequent interplanetary missions.[7][15]

Mapping cycle 6

- Goal: Collect high-resolution gravity data and conduct radio science experiments.[16]

- April 16, 1994 - October 13, 1994

The sixth and final orbiting cycle was another extension to the two previous gravimetric studies. Toward the end of the cycle, a final experiment was conducted, known as the "windmill" experiment to provide data on the composition of the upper atmosphere of Venus. Magellan performed 1,783 orbits before the end of the cycle on October 13, 1994, when the spacecraft entered the atmosphere and disintegrated.[7]

Windmill experiment

- Goal: Collect data on atmospheric dynamics.[17]

- September 6, 1994 - September 14, 1994

- In September 1994, the orbit of Magellan was lowered to begin the "windmill experiment". During the experiment, the spacecraft was oriented with the solar arrays broadly, perpendicular to the orbital path, where they could act as paddles as they impacted molecules of the upper-Venusian atmosphere. Countering this force, the thrusters fired to keep the spacecraft from spinning. This provided data on the basic oxygen gas-surface interaction. This would be useful for understanding the impact of upper-atmospheric forces which aided in designing future Earth-orbiting satellites, and methods for aerobraking during future planetary spacecraft missions.[15][17][18]

Discoveries

Rendered image of Venus rotating using data gathered by Magellan.

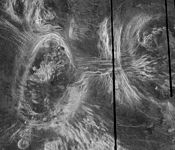

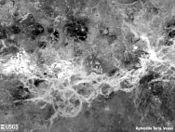

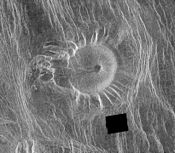

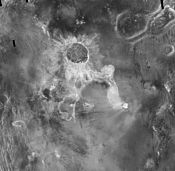

- Study of the Magellan high-resolution global images is providing evidence to understand the role of impacts, volcanism, and tectonism in the formation of Venusian surface structures.

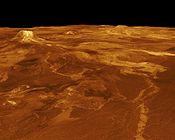

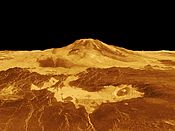

- The surface of Venus is mostly covered by volcanic materials. Volcanic surface features, such as vast lava plains, fields of small lava domes, and large shield volcanoes are common.

- There are few impact craters on Venus, suggesting that the surface is, in general, geologically young - less than 800 million years old.

- The presence of lava channels over 6,000 kilometers long suggests river-like flows of extremely low-viscosity lava that probably erupted at a high rate.

- Large pancake-shaped volcanic domes suggest the presence of a type of lava produced by extensive evolution of crustal rocks.

- The typical signs of terrestrial plate tectonics - continental drift and basin floor spreading - are not evident on Venus. The planet's tectonics is dominated by a system of global rift zones and numerous broad, low domical structures called coronae, produced by the upwelling and subsidence of magma from the mantle.

- Although Venus has a dense atmosphere, the surface reveals no evidence of substantial wind erosion, and only evidence of limited wind transport of dust and sand. This contrasts with Mars, where there is a thin atmosphere, but substantial evidence of wind erosion and transport of dust and sand.

Study of the Magellan high-resolution global images is providing evidence to better understand Venusian geology and the role of impacts, volcanism, and tectonism in the formation of Venusian surface structures.

Magellan created the first (and currently the best) near-photographic quality, high resolution radar mapping of the planet's surface features. Prior Venus missions had created low resolution radar globes of general, continent-sized formations. Magellan, however, finally allowed detailed imaging and analysis of craters, hills, ridges, and other geologic formations, to a degree comparable to the visible-light photographic mapping of other planets. Magellan's global radar map will remain the most detailed Venus map in existence for the foreseeable future, although the planned Russian Venera-D may carry a radar that can achieve the same, if not better resolution as the radar used by Magellan.

Volcanoes as seen in the Fortuna region of Venus.Addams crater.An unusual volcanic edifice in the Eistla region. Media related to Magellan radar imagery at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Magellan radar imagery at Wikimedia CommonsEnd of mission

On September 9, 1994, a press release outlined the termination of the Magellan mission. Due to the degradation of the power output from the solar arrays and onboard components, and having completed all objectives successfully, the mission was to end in mid-October. The termination sequence began in late August 1994, with a series of orbital trim maneuvers which lowered the spacecraft into the outermost layers of the Venusian atmosphere to allow the Windmill experiment to begin on September 6, 1994. The experiment lasted for two weeks and was followed by subsequent orbital trim maneuvers, further lowering the altitude of the spacecraft for the final termination phase.[17]

On October 11, 1994, moving at a velocity of 7-kilometers/second, the final orbital trim maneuver was performed, placing the spacecraft 139.7-kilometers above the surface, well within the atmosphere. At this altitude the spacecraft encountered tremendous friction, raising temperatures on the solar arrays to 126-degrees Celsius.[14][19]

On October 13, 1994 at 10:05:00 UTC, communication was lost when the spacecraft entered radio occultation behind Venus. The team continued to listen for another signal from the spacecraft until 18:00:00 UTC, when the mission was determined to have concluded. Although much of Magellan was expected to vaporize due to atmospheric stresses, some amount of wreckage is thought have hit the surface by 20:00:00 UTC.[14][15]

Quoted from Status Report - October 13, 1994[14] "Communication with the Magellan spacecraft was lost early Wednesday morning, following an aggressive series of five Orbit Trim Maneuvers (OTMs) on Tuesday, October 11, which took the orbit down into the upper atmosphere of Venus. The Termination experiment (extension of September "Windmill" experiment) design was expected to result in final loss of the spacecraft due to a negative power margin. This was not a problem since spacecraft power would have been too low to sustain operations in the next few weeks due to continuing solar cell loss. Thus, a final controlled experiment was designed to maximize mission return. This final, low altitude was necessary to study the effects of a carbon dioxide atmosphere.

The final OTM took the periapsis to 139.7 km (86.8 mi) where the sensible drag on the spacecraft was very evident. The solar panel temperatures rose to 126 deg. C. and the attitude control system fired all available Y-axis thrusters to counteract the torques. However, attitude control was maintained to the end.

The main bus voltage dropped to 24.7 volts after five orbits, and it was predicted that attitude control would be lost if the power dropped below 24 volts. It was decided to enhance the windmill experiment by changing the panel angles for the remaining orbits. This was also a preplanned experiment option.

At this point, the spacecraft was expected to survive only two orbits.

Magellan continued to maintain communication for three more orbits, even though the power continued to drop below 23 volts and eventually reached 20.4 volts. At this time, one battery went off-line, and the spacecraft was defined as power starved.

Communication was lost at 3:02 AM PDT just as Magellan was about to enter an Earth occultation on orbit 15032. Contact was not re-established. Tracking operations were continued to 11:00 AM but no signal was seen, and none was expected. The spacecraft should land on Venus by 1:00 PM PDT Thursday, October 13, 1994."

See also

References

- ^ a b "V-gram. A Newsletter for Persons Interested in the Exploration of Venus" (PDF) (Press release). NASA / JPL. 1986-03-24. http://hdl.handle.net/2060/19860023785. Retrieved 2011-02-21.

- ^ a b c d e f g Guide, C. Young (1990). Magellan Venus Explorer's Guide. NASA / JPL. http://www2.jpl.nasa.gov/magellan/guide.html. Retrieved 2011-02-22.

- ^ a b c d e f g Ulivi, Paolo; David M. Harland (2009). Robotic Exploration of the Solar System Part 2:Hiatus and Renewal 1983–1996. Springer Praxis Books. pp. 167–195. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-78905-7. http://www.springerlink.com/content/978-0-387-78904-0/. Retrieved 2011-02-22.

- ^ a b "Magellan". NASA / National Space Science Data Center. http://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/nmc/masterCatalog.do?sc=1989-033B. Retrieved 2011-02-21.

- ^ Croom, Christopher A.; Tolson, Robert H.. "Venusian atmospheric and Magellan properties from attitude control data". NASA Contractor Report. NASA Technical Reports Server. http://hdl.handle.net/2060/19950005278. Retrieved 8 October 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "SPACE SHUTTLE MISSION STS-30 PRESS KIT" (Press release). NASA. APRIL 1989. http://science.ksc.nasa.gov/shuttle/missions/sts-30/sts-30-press-kit.txt. Retrieved 2011-02-22.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n "Mission Information: MAGELLAN" (Press release). NASA / Planetary Data System. 1994-10-12. http://starbrite.jpl.nasa.gov/pds/viewMissionProfile.jsp?MISSION_NAME=MAGELLAN. Retrieved 2011-02-20.

- ^ a b c Magellan: The unveiling of Venus. NASA / JPL. 1989. http://hdl.handle.net/2060/19890015048. Retrieved 2011-02-23.

- ^ "Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR)". NASA / National Space Science Data Center. http://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/nmc/experimentDisplay.do?id=1989-033B-01. Retrieved 2011-02-24.

- ^ "PDS Instrument Profile: Radar System". NASA / Planetary Data System. http://starbrite.jpl.nasa.gov/pds/viewInstrumentProfile.jsp?INSTRUMENT_ID=RDRS&INSTRUMENT_HOST_ID=MGN. Retrieved 2011-02-27.

- ^ DALLAS, S. S. (1987). "The Venus Radar Mapper Mission". Acta Astronautica (Pergamon Journals Ltd) 15 (2): 105–124. doi:10.1016/0094-5765(87)90010-5.

- ^ a b Roth, Ladislav E; Stephen D Wall (1995). The face of Venus : the Magellan radar-mapping mission. Washington, D.C.: National Aeronautics and Space Administration. http://ntrs.nasa.gov/archive/nasa/casi.ntrs.nasa.gov/19960023593_1996031327.pdf. Retrieved 2011-02-21.

- ^ Pettengill, Gordon H.; Peter G. Ford, William T. K. Johnson, R. Keith Raney,Laurence A. Soderblom (1991). "Magellan: Radar Performance and Data Products". Science (American Association for the Advacement of Science) 252 (5003): 260–5. Bibcode 1991Sci...252..260P. doi:10.1126/science.252.5003.260. JSTOR 2875683. PMID 17769272.

- ^ a b c d "Magellan Status Report - October 13, 1994" (Press release). NASA / JPL. 1994-10-13. http://www2.jpl.nasa.gov/magellan/status941013.html. Retrieved 2011-02-22.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Grayzeck, Ed (1997-01-08). "Magellan: Mission Plan". NASA / JPL. http://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/planetary/mgncycles.html. Retrieved 2011-02-27.

- ^ a b c d e f "Magellan Mission t a Glance" (Press release). NASA. http://www2.jpl.nasa.gov/magellan/fact.html. Retrieved 2011-02-21.

- ^ a b c "Magellan Begins Termination Activities" (Press release). NASA / JPL. 1994-09-09. http://www2.jpl.nasa.gov/magellan/status940909.html. Retrieved 2011-02-22.

- ^ "Magellan Status Report - September 16, 1994" (Press release). NASA / JPL. 1994-09-16. http://www2.jpl.nasa.gov/magellan/status940916.html. Retrieved 2011-02-22.

- ^ "Magellan Status Report - October 1, 1994" (Press release). NASA / JPL. 1994-10-01. http://www2.jpl.nasa.gov/magellan/status941001.html. Retrieved 2011-02-22.

External links

- Magellan homepage

- Magellan mission description and data

- Magellan images

- Magellan Mission Profile by NASA's Solar System Exploration

- http://library.thinkquest.org/J0112188/magellan_probe.htm

- http://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/nmc/tmp/1989-033B.html

Spacecraft missions to Venus Flybys

Orbiters Descent probes Landers Balloon probes Future missions Proposed missions Venus In-Situ Explorer (study)See also Bold italics indicates active missions Categories:- Venus spacecraft

- NASA probes

- Destroyed extraterrestrial probes

- 1989 in spaceflight

- Space radars

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.