- Congo Free State Propaganda War

-

The Congo Free State Propaganda War (1884–1912) occurred during the era when European Imperialism was at its greatest height. Demand for oriental goods remained the driving force behind European imperialism, and (with the important exception of British East India Company rule in India) the European stake in Asia remained confined largely to trading stations and strategic outposts necessary to protect trade. Industrialization, however, dramatically increased European demand for Asian raw materials, which diminished greatly; and the severe Long Depression of the 1870s provoked a scramble for new markets for European industrial products and financial services. Thus, Europe turned to Africa.

The Congo Free State Propaganda War is one particular event during the African colonization which involved King Leopold II of Belgium and his tyrannical rule over the Congo Free State. What makes this event so worthy of discussion is not just the horrors that occurred, but rather the world wide media campaign waged by both King Leopold himself and the numerous opponents to the Congo Free State. Some of these individuals failed as Leopold's media prowess became too much. But one man, Edmund Dene Morel, successfully campaigned against Leopold and created a public focus upon the violence of Leopold’s rule. Morel utilized every corner of mass media[1] of that time, and began a direct world-wide political war with a powerful monarch.

Edmund Dene Morel successfully created a public focus upon the violence of Leopold’s rule in the Congo due to his expansive employment of mass media; thus it resulted in the evident demise of the Congo Free State and Leopold’s reputation. He started out with newspapers and pamphlets. Then he expanded with several books, and an international organization. But he also gave brilliant speeches and interviews. He dwelled upon words that would catch the ears of the public and make them think. No matter how Morel wrote or spoke about his ideas, he always included undeniable evidence such as testimony, reports, pictures, facts and numbers; all obtained from missionaries, friends, and allies. Morel’s expansive employment of the media, combined with his writing and evidence, became the end of Leopold’s reign.

Contents

Background

Leopold's Acquisition

Leopold fervently believed that overseas colonies were the key to a country's greatness, and he worked tirelessly to acquire colonial territory for Belgium. Neither the Belgian people nor the Belgian government was interested, however, and Leopold eventually began trying to acquire a colony in his private capacity as an ordinary citizen. The Belgian government lent him money for this venture.

After a number of unsuccessful schemes for colonies in Africa or Asia, in 1876 he organized a private holding company disguised as an international scientific and philanthropic association, which he called the International African Society. The IAA created an executive council with King Leopold as chair, a flag, and adopted goals that the organization wished to achieve. The IAA’s goals written by Leopold are as follows: to suppress the slave trade in Equatorial Africa, to unite the native tribes, modernize the peoples of the Congo River, bring morality and a sense of sin to the natives, and advance the economy of the peoples. Leopold used these goals to justify his desire to colonize the Congo region of Africa. After the conference Leopold told the members and reporters:

To open up civilization the only part of our globe which it has not yet penetrated, to pierce the darkness in which entire populations are enveloped, is, I venture to say, a crusade worthy of its age of progress,…Need I say that, in bringing you to Brussels, I have not been influenced by selfish views.[2]

Unbeknown to the members of the conference, the goals set forth by Leopold were no more than a façade to cover up his true intentions of creating a private kingdom that he alone may profit from.

In 1878, under the auspices of the holding company, he hired the famous explorer Henry Morton Stanley to establish a colony in the Congo region.[3] Before Stanley left for Africa, Leopold created le Comité d’Études du Haut Congo, a branch of the IAA, commissioned to be the sole exploratory committee with a purse of a million francs in gold. Le Comité, chaired by Stanley, promised to abide by the IAA’s goals set forth by Leopold. Le Comité became another façade for Leopold’s Public Relations (PR) campaign to justify his colonization of the Congo. By creating an expedition that followed the IAA’s goals, Leopold would avoid questioning from anti-imperialists. But, by heading it with Stanley, Leopold assured himself that his true intentions of building his kingdom would be carried out.

- Much diplomatic maneuvering resulted in the Berlin Conference of 1884–85, at which representatives of fourteen European countries and the United States recognized Leopold as sovereign of most of the area he and Stanley had laid claim to. During the spring of 1884, Leopold started a campaign to convince the Great Powers that the Congo Free State would be a sovereign nation and that he would be its exclusive head of state. With his neighbors pressing him, King Leopold had to figure out how he could preserve the large area of land that he so lavishly devoted his time and money to. “He finally conceived the idea of a Congo Free State, with himself as the Sovereign ruler.”[4] To appease his critics, Leopold called the area of land the Congo Free State, suggesting individual, economic, and religious freedoms would be a part of the State.

Using Public Diplomacy

With his neighbors pressing him, King Leopold had to figure out how he could preserve the large area of land that he so lavishly devoted his time and money to. “He finally conceived the idea of a Congo Free State, with himself as the Sovereign ruler.”[5] To appease his critics, Leopold called the area of land the Congo Free State, suggesting individual, economic, and religious freedoms would be a part of the State. During the spring of 1884, Leopold started a campaign to convince the Great Powers that the Congo Free State would be a sovereign nation and that he would be its exclusive head of state. Leopold began a publicity campaign in Britain, drawing attention to Portugal's slavery record to distract critics and offering to drive slave traders from the Congo basin. He also secretly told British merchant houses that if he was given formal control of the Congo for this and other humanitarian purposes, he would then give them the same most favored nation (MFN) status Portugal offered. At the same time, Leopold promised Otto Van Bismarck he would not give any one nation special status, and that German traders would be as welcome as any other.

Leopold then offered France the support of the Association for French ownership of the entire northern bank, and sweetened the deal by proposing that, if his personal wealth proved insufficient to hold the entire Congo, as seemed utterly inevitable, that it should revert to France. He also enlisted the aid of the United States, sending President Chester A. Arthur carefully edited copies of the cloth-and-trinket treaties British explorer Henry Morton Stanley claimed to have negotiated with various local authorities, and proposing that, as an entirely disinterested humanitarian body, the Association would administer the Congo for the good of all, handing over power to the locals as soon as they were ready for that grave responsibility.

Leopold worked continuously to convince the President of the United States, along with the U.S. Congress, to officially recognize the treaties and the Congo Free State. The United States, with its growing international influence as an economic and military power, became vital to Leopold. His Public Relations campaign used the fear and desires of the politicians. For example, with southern Congressman, Leopold’s men informed them that the Congo Free State could be the new home, or a place of work, for the freed slaves of the south. The southern Congressmen loved the idea of moving the African Americans back to Africa. With the southern vote, Leopold’s agents effectively lobbied the rest of Congress. Leopold used the economic growth of the United States to his advantage. He promised the President that the U.S. could openly and freely trade with the Congo Free State, in turn gaining a profit for its economy.

In April, the U.S. Congress decided that the treaties, signed by the chiefs, were of legal standing; therefore, Leopold’s Congo would be considered a sovereign state under the rule of the Belgian king accordance to the IAA and its goals as the ruling government. France’s recognition soon followed, and then Germany, and soon after all the other European nations. With the IAA as a legitimate government, governing a recognized sovereign state, Prince Otto Van Bismarck invited King Leopold to discuss African Affairs amongst the Great Powers of Europe.

Thus on November 15, 1884 the International Conference met to resolve “the African question”. During a long and tremendous debate, and after ten sittings, the Great Powers finally agreed on a solution. The solution, made without any input from the natives of Africa, or without any care to tribal politics, defined the borders for the colonizing countries. The Congo Free State encompassed nearly a million square miles, the largest claim of Central Africa by any sovereign

Red Rubber

The Congo produced a great amount of resources for those who harvested them. Ivory was one resource that Leopold profited from. Although limited in amount, ivory provided Leopold enough money to build up the Congo State, and still have enough for his lucrative spending habits. But one resource caused Leopold to become extremely wealthy; rubber. Rubber production became a primary product of the Congo. Rubber vines were prominent throughout central Africa; however, the process of harvesting the rubber from the vine is more difficult than that from a tree. This process raised the prices for African rubber, thus allowing the Asian market to sell more.

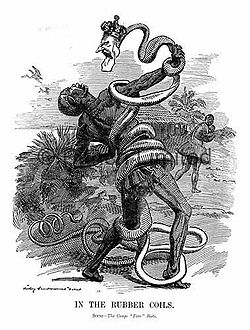

Leopold demanded a very productive system of extracting rubber with little to no expense. To combat the expenses of production, as well as to please Leopold, Leopold’s agents used forced labor, or slave labor, to get rubber and ivory; a clear violation of the Berlin Conference Act.[6] In order to make sure high production numbers became a constant, Leopold used an army of production enforcers called the Force Publique (FP). Leopold initially conceived the FP in 1885 when he ordered his Secretary of the Interior to create military and police forces for the state. Soon afterwards, in 1886 Leopold dispatched a number of Belgian officers and noncommissioned officers to the territory to create this military force. The FP's officer corps consisted entirely of whites, who comprised a mixture of Belgian regular soldiers, as well as mercenaries from other countries drawn by the prospect of wealth or simply attracted by the allure and adventure of service in Africa. The enlisted men consisted of whites who lived in the Congo for many years, and natives who could be trusted to carry a weapon.

Humanitarian Disaster

The FP became the slave drivers of the natives, forcing them to work on their own land for nothing. They also enforced Leopold’s law that the chiefs could not sell any rubber and ivory to any other nation. If caught the FP would then kill everyone in the tribe, burn the huts, and make the chief a slave for life. The FP’s brutal methods included rape, mutilations, village destruction, killing of individuals, and mass murder to motivate the slaves, and locals, to produce a higher output. But the most common of all the FP’s practices were the cutting off of right hands and daily whippings of the slaves. Everything that the FP did is a complete contradiction to what Leopold stated as a goal to stop slavery in Equatorial Africa.

This brutality would later be dubbed “Red Rubber” – for the rubber stained by the blood of the Africans obtained it. The numbers are still debated, but the total deaths caused by the FP are in the tens of millions, and the total number of mutilations is even higher. Leopold constantly denied any knowing of what was going on in his Congo. And it is estimated that he gained almost $1 billion of today’s dollars in profit. Even though Leopold was able to profit so much, he did not go unnoticed.

The Media War

The Missionaries and the Congo

King Leopold worried about foreigners entering the Congo because he feared they might steal from him; however he allowed several hundred foreign Protestant Missionaries to go to the Congo. The missionaries came from all the countries that Leopold, at the time, hoped to gain favor from; England, the United States, and Sweden. Leopold could not turn down those who wanted to “civilize” the Africans as part of his own Public Relations campaign upon his obtaining of the Congo Free State. The missionaries went to the Congo to evangelize, fight polygamy, and create a fear of sin within the Africans. But, the missionaries had trouble finding Congolese to convert and save. Upon the sight of any white man entering the region, the Congolese would run and hide.

One British missionary wrote about a time when his African congregation asked, “Has the Savior you tell us of any power to save us from the rubber trouble?” The missionaries started to became aware of the bloody transactions happening around their posts. One Swedish missionary noted a sorrowful song about death and tyranny that many of the natives sang at his post. The missionaries began to protest the violence that they witnessed to Leopold through personal letters, as well as through letters to newspapers and magazines. Unfortunately, their efforts had little effect in drawing attention to the situation due to lack of interest, and that of Leopold himself.

William Sheppard

In the late 1880s William Sheppard, an African-American Protestant missionary, started to write to American newspapers and magazines about the mutilations and murder that he witnessed. With threats of taxation and exportation, Leopold put a stop to Sheppard’s writing.

E.V. Sjöblom

Swedish Baptist missionary, E.V. Sjöblom spoke to all who would listen and published a detailed attack on the Congo’s rubber terror in the Swedish press in 1896. The article turned up in newspapers in other countries. Sjöblom took his concerns to a public meeting with the press present. He spoke about the FP and their brutal ways. The Congo State officials, who put on a counterattack of newspaper articles, letters, and comments from Leopold, in the Belgian and British press, quickly silenced Sjöblom. The missionary never spoke up again.

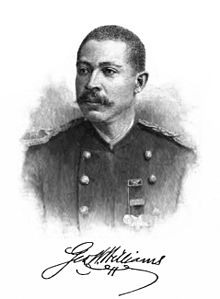

George Washington Williams

George Washington Williams (October 16, 1849 – August 2, 1891) The most well known fighter against Leopold was Col. George Washington Williams. Williams was a freed slave who served in the Union army during the Civil War. After attending many colleges and universities, Williams entered a seminary and became a pastor of the Twelfth Baptist Church. After moving to Washington D.C., he commenced his journalism career by starting a national black newspaper, the Commoner. The newspaper folded and Williams tried again in Cincinnati, but again failed. Later he became a well-respected American historian through many of his writings and lectures.

In 1889, Williams received a job to be a journalist for the European press syndicate. After an interview with Leopold, Williams took it upon himself to go to the Congo and see the “Christian Civilization” in action. As witness to the actions of the FP, Williams took it upon himself to write a letter to Leopold entitled An Open Letter to His Serene Majesty Leopold II, King of the Belgians and Sovereign of the Independent State of Congo, sent in early April 1891. In the twelve-page letter he noted his disbelief: “How thoroughly I have been disenchanted, disappointed, and disheartened.”[7] 16 In the last pages, Williams outlined a list of crimes that he thought Leopold committed; one being manipulation of the general public.

After sending the letter to Leopold, he then turned to the President of the United States in another letter entitled A Report upon the Congo-State and Country to the President of the Republic of the United States of America. In this letter Williams describes how Leopold manipulated the United States. By the time President Benjamin Harrison received his letter, the Open Letter appeared in European and American newspapers. On the 14th of April 1891, The New York Times ran a front-page article with the full list of allegations. Shortly before his death he travelled to King Leopold II's Congo Free State and his open letter to Leopold about the suffering of the region's inhabitants at the hands of Leopold's agents, helped to sway European and American public opinion against the regime running the Congo,[8] under which some 10 million people lost their lives. .

Leopold vs. the Missionaries

Leopold was successful with public relations as king. He and his Public Relations Minister had control over much of the European Press Corps. The Minister employed newspaper editors to run articles about the good deeds of Leopold. Leopold himself did interviews talking about his dreams and aspirations for the Congo and its benefit. He knew how to deploy his charm and stop the articles from garnishing any credibility. With threats of taxation and exportation, Leopold put a stop to Sheppard’s writing. Afterwards, Leopold demanded that the missionaries direct all concerns to him and not to the press.

One day after the New York Times article, which detailed the allegations, Leopold’s supporters in America submitted an article that accused Williams of being a fraud. The headline read “HE PROSPERED FOR A TIME, BUT HIS TRUE CHARACTER WAS LEARNED.”[9] The article accused Williams of living a lie, and accused him of committing adultery. During the late summer of 1891 the Belgian Parliament defended Leopold and gave a forty-five page report to the press circuit, effectively refuting William’s accusations. Before Williams could even defend himself he passed away on August 2 of the same year. His reputation became tarnished, and his humanitarian work became a failure.

The many foreign missionaries, who witnessed the atrocities, had little media savvy or political clout. The public readily dismissed Leopold’s critics from British humanitarian societies as relics of past battles like Abolitionism. And those critics, like the missionaries, became dismissed as people who were always upset about something in some obscure corner of the world. The use of the media for the missionaries became a backlash that tarnished their reputations. The campaign, however, did not die. It would take one man to fully revitalize the missionaries’ work, and in the process use the media with a better effect.

E.D. Morel vs. King Leopold

In 1891, Morel obtained a clerkship with Elder Dempster, a Liverpool shipping firm. To increase his income and support his family, from 1893 Morel began writing articles against French protectionism, which was damaging Elder Dempster's business. He came to be critical of the Foreign Office for not supporting Africa and African decolonisation movements. His vision of Africa was influenced by the books of Mary Kingsley, an English traveller and writer, which showed sympathy for African peoples and a respect for different cultures that was very rare amongst Europeans at the time.

Elder Dempster had a shipping contract with the Congo Free State for the connection between Antwerp and Boma. Groups such the Aborigines' Protection Society had already begun a campaign against alleged atrocities in Congo. Due to his knowledge of French, Morel was often sent to Belgium, where he was able to view the internal accounts of the Congo Free State held by Elder Dempster. The knowledge that the ships leaving Belgium for the Congo carried only guns, chains, ordnance and explosives, but no commercial goods, while ships arriving from the colony came back full of valuable products such as raw rubber and ivory, led him to the opinion that Belgian King Leopold II's policy was exploitative. According to the Belgian Prof. Daniël Vangroenweghe, Leopold gained 1,250 million present day[when?] euros from the exploitation of the Congolese people, mainly from rubber. Other Belgian sources calculated that the profits from the Congolese exploitation prior to 1905 were some 500 million present-day euros[when?].

The gains from the exploitation of rubber through the state and other companies like the Anglo-Belgian India Rubber Company (ABIR) were huge. The original value of the ABIR shares was 500 francs (1892 gold francs). In 1903 the shares had risen to 15,000 gold francs. The company felt obliged to let the Bourgeoisie share profits with the upper class. The dividend in 1892 was 1 franc. In 1903 the dividend was 1,200 francs, more than the double of the original price of a share. These enormous gains came from horrible exploitation, and the equator region became a green hell. The scope of the destruction, together with disease and famine from forced labor, killed half of the population of the colony.

Newspapers

Between 1890 and 1920, the period known as the “golden age” of print media, newspapers played a role as disseminators of revolutionary propaganda. As printing technology developed, newspaper prices dropped. Thus audience and readership grew. At the turn of the century a “fascination of a mass market of newspaper conscious in a world that was increasingly influenced by European Imperialism”[10] developed due to international press syndicates and the telegraph. The interest of European Imperialism in newspapers became so great that stories of it could be found front page. Morel used this interest to his advantage, as he presented his case in his own newspaper.

West African Mail, the main media outlet for Morel, started out as small newspaper consisting of articles written by Morel, letters from missionaries, maps, cartoons and pictures; all “to meet the rapidly growing interest in west and central African questions".[11] Morel knew exactly how to fit his message to his audience. John Holt, a businessman and Morel’s long time friend, helped fund the start up of the newspaper. Later on supporters invested in the paper to keep it alive. However, the cost of the paper is still undetermined. But first Morel needed to draw attention to his newspaper. As a long time journalist Morel knew how to draw attention to his articles. He wrote a five part series entitled Trading Monopolies in West Africa. He first wrote about stories pertaining free trade and native rights.

"Free Trade in West Africa, free trade for all; free trade for the Englishmen in a French colony, and in a German colony… There is plenty of room for the free, unfettered commerce of all the Powers of Europe of the Western Continent of Africa, and the greater(the natives), the attractions given to the trade in an individual colony… the more certain the contentment and the producing power of its inhabitants."[12]

But then he took a new direction in the last series. He did forget about those suffering, thus he began to write about the tragedy with the slaves. Morel laced his articles with descriptive words to emphasize the need for concern. Some articles contained adjectives like: evil, bloody, viscous, horrific and violent.[13]

"The rubber shipped home by the Congo companies…is stained with blood of hundreds of negroes.” “This hideous structure of sordid wickedness.,” he called it. “Blood is smeared all over the Congo State, its history is blood-stained, its deeds are bloody, the edifice it has reared is cemented in blood—the blood of unfortunate negroes, spilled freely with the most sordid of all motives, monetary gain."[14]

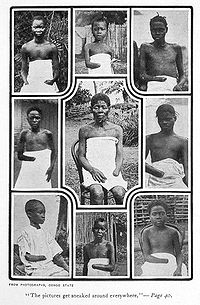

By using these types of descriptive words Morel could keep the reader’s attention due to an overall public fascination with death and violence. Morel simply capitalized on this nature by publishing the most horrific pictures and grotesque stories. This consequently caused people to focus on the Congo.

Besides publishing articles in his own newspaper, Morel also published either the same article, or a different one talking about it, in major British and Belgian papers. The different articles had little information, but Morel put enough violent content to attract readers to his paper. At this point in 1902 it is difficult to judge whether the newspaper articles worked to draw public attention to Congo atrocities. It isn’t until 1903 when there is evidence showing that Morel’s writings are actually working. A book entitled Civilization in Congo-land, published in January of 1903, by H.R. Fox Bourne, secretary of the Aborigines Protection Society, reinforced the humanitarian aspect of Morel’s argument. Various organizations passed resolutions to the Government stating that action must be taken. An advocate Sir Charles Dilke, of the British of Commons, took many of the organizations’ concerns to Parliament for discussion.

Pamphlets

At the start of 1903, Morel took to his pen and wrote his first pamphlet, The Congo Horrors. A pamphlet is an unbound booklet that is without a hard cover or binding. It may consist of a single sheet of paper that is printed on both sides and folded in half, in thirds, or in fourths (called a leaflet), or it may consist of a few pages that are folded in half and stapled at the crease to make a simple book. In contrast to newspapers, the simple production allowed pamphlets to be cheaper to purchase, thus allowing for a greater marketability to a more general audience. Pamphlets have also long been an important tool of political protest, as seen in the American Revolution, and political campaigning for similar reasons.

Morel’s The Congo Horrors reached a greater general public that he may have not yet reached. What the newspaper contained, usually the pamphlet contained as well. He made sure this time to emphasize the religious implications, free trade abuses, and accusations towards Leopold creating accountability. “It has come to my conclusion that the murders and profiteering of the Congo are a result of neglect to civilize, and King Leopold is the proprietor.”[15] This pamphlet caught the eyes of high British officials such as Sir Charles Dilke and Roger Casement.

With the advent of Parliamentary debate, Morel continued to write pamphlets such as The Scandal of the Congo, The Treatment of Women and Children of the Congo (published in America in the African Studies Journal), and The New African Slavery (published in the International Union of London). All the pamphlets contained information and testimony, from the missionaries, of the brutality taking place at the time of the inquiry. The public began to pressure Parliament to do something about the atrocities that Morel wrote about.

Later in the year of 1903, Morel brought out a large pamphlet of 112 pages entitled The Congo Slave State. This pamphlet was perhaps the strongest and fiercest indictment published of the Congo State rule. It contained a full and detailed description of the Leopoldian system as carried out in all the divisions of the Congo. It also contained illustrations of maps of the various areas discussed, reports from Parliament, and descriptions of the atrocities. Sir Charles Dilke introduced copies of the pamphlet to Parliament, as copies became distributed to principle newspapers and to America. The pamphlet caused considerable sensation throughout Parliament as resolutions passed to stop the slavery in the Congo.

Books

[16] Before the establishment of the CRA in 1904, Morel released two books pertaining to West Africa. The first book, entitled Affairs of West Africa,[17] was his most important book. The book consisted of illustrations and maps, along with an extensive knowledge of history, the inhabitants, flora and fauna, physical characteristics, industries, trade and finances; all from a man who never stepped foot in West Africa. He received all of his information from traders and shipping crews, during his days working for Elder Dempster, and from many of his missionary contacts. As insignificant as it may seem, this portion of the book provided the credibility Morel needed for his future arguments. Morel concluded his book with attacks on Leopold and the Congo Free State administration. He contrasted the Congo Free State to the success of the French Congo, commemorating the French administration for their admirable efforts within their West African colonies. He then asked for sympathy and understanding, from the English and French, on the issue of West Africa.

Newspapers reviewed his first book, with some being good and some being bad. In The Daily Chronicle Sir Harry Johnston wrote: “Mr. Morel’s indictment is one of the most terrible things ever written, if true.”[18] The Times also provided a glowing review of the book:

It is with great satisfaction that the public will welcome a contribution to our general knowledge on the subject… The sufferings of which the picture was given to the world in Uncle Tom’s Cabin are as nothing to those which Mr. Morel represents to be habitual accomplishments of the acquisition of rubber and ivory by the Belgian companies.[19]

This type of positive review, and other reviews, which syndicated in newspapers in other countries, helped set up a base readership for his writings, as Morel only hoped, grew in time. Even with only one known bad review from the Morning Post pertaining to what they believed was a book comparing the French Congo to Leopold’s Congo Free State. Morel was quick with a response, another book. A bad review in a newspaper can have severe consequences, especially when one is trying to garner public awareness for an issue.

Morel’s new book The British Case in the French Congo, released only three months after his first, made sure that there was a clarification that Morel truly admired the French and their efforts, and again blame the Congo Free State for the evil in West Africa with a full explanation. The second book again received great praise from the newspapers, even from the Morning Post. Readership and support grew so great that the public demanded that the government take action. Thus on May 20, 1903 Parliament supported a resolution to allow the British Government to negotiate with the Powers over the atrocities. Without Morel’s two books the general public would not have cared about the issue, and would not have pressured their representatives to debate the issue in Parliament. Parliament even noted at the end that “great gratitude was due” to Morel for creating such a great public awareness.[20]

However, the crown jewel of the media blitz was his third book, King Leopold’s Rule in Africa.[21] What made this book so important was the use of photographs of mutilated women and children. For the most part he let the pictures speak for themselves. But it was how he wrote his book that made it so effective. “Over and over again in his book did Morel hammer in the argument.”[22] Morel also uses an idea that the world is in it together. That the world must come together to fight.

“In the name of humanity, of common decency and pity, for honour’s sake, if for no other cause, will not the Anglo-Saxon race – the Governments and the peoples of Great Britain and the United States, who between them are primarily responsible for the creation of the Congo State –make up their minds to handle this monstrous outrage resolutely, and so point the way, and set an example which others would then be compelled to follow? In that hope, with an ever present consciousness of inadequacy to portray the greatness of the evil and the greatness of responsibility, the author submits this volume to the public.”[23]

It can be argued that from past experiences, Morel knew that this book would appear in newspapers and syndicated throughout the Press. Why else would he make a compelling plea to the public? His words and facts from the book did appear in book reviews in newspapers all over Europe and the US. To Morel’s surprise the reviewers described the horrific pictures and stories in full detail. This benefited him due to the public fascination with violence. If a reviewer gave a snippet of how vivid the book was, then the reader would want to buy it and read it in full. Morel could not ask for more from the reviewers. But, what did Leopold do about all the claims against him, and the great public protest?

Congo Reform Association

As Morel’s writings stirred up public feelings, for the “Congo Question”, within Great Britain, Parliament publicly raised its objections to the murders, slavery, and economic dominance. In the wake of this suspicion, Parliament created an international commission to investigate conditions in the Congo. Roger Casement, a British Consul to Africa and an acquaintance of Morel, went to the Congo to write up a report for the British Government. Casement spent time interviewing missionaries, natives, and others living in the Congo such as riverboat captains and railroad workers. Thus, Casement returned to England with a report telling of some of the most appalling events ever heard up to that time.

Many considered the report to be the most damning exposure of exploitation in Africa that has ever startled and shocked an easy going world. The publication of the report was of decisive importance in at least three ways. First, a respectable British Consul, who the British Foreign office suggested, wrote the report. Second, the document contained thirty-nine pages of testimony by Casement and others; 23 pages consisted of an index with facts. And lastly, Morel published the report in as many media outlets as he could to expose it to a larger audience, thus in return creating a larger public awareness. It produced a profound and widespread feeling in Britain that the administrative system of the Congo State must be reformed. The British Government commended Casement for his work and knighted him. Morel published the Casement Report in The West African Mail to provide the general public with the hard evidence of the abuses occurring. Newspapers around the world, such as The New York Times, The Paris Press, and Italian and Australian newspapers, all reported on the Casement Report. With the international newspapers reporting on the campaign, Morel realized that his work needed to expand beyond the British Isles.

In order to bring international attention to the natives’ plight, Casement and Morel met in Dublin to discuss the situation. Morel liked Casement from the start and believed he had a good heart.[24] Casement convinced Morel that an organization would have to be formed in order to combat Leopold’s abuses in the Congo. Thus, in November 1903 in the Irish house of Roger Casement, the Congo Reform Association (CRA) developed. Casement put forward £ 100 as a start up fund. Morel went back to Liverpool to begin the new organization. He drew upon the book The Heart of Darkness as inspiration for what he called “the most powerful thing ever written on the subject”.[25] Casement deliberately absented himself from the launch of the Congo Reform Association, at the Philharmonic Hall in Liverpool on March 23, 1904, because he did not want his celebrity to be the only reason people joined.

Joining and being involved in an organization at this time was a social norm. An organization is a social arrangement which pursues collective goals, which controls its own performance, and which has a boundary separating it from its environment. During the early 20th century there was a desire for belonging, and joining an organization gave that sense of belonging. Organizations also provided a forum for those who with strong feelings about an issue; for example, the Congo. A structured organization allowed a group of people to effectively communicate their goals and ideas to a larger mass of people. An organization became the perfect way for Morel to take the Congo abuses international because if offered that forum and use of word of mouth.

The founding manifesto preambled with an impressive list of names including the African businessman and entrepreneurs, John Holt, the historian, John Morley, the Presbyterian Minister, Reverend RJ Campbell and the Quaker philanthropist, W.A. Cadbury, aka George Cadbury of the Cadbury Chocolate Corp.. Other public names included four bishops and a dozen influential peers of the realm. The more people with a well-known name that joined, the more creditability Morel and the organization receive. This is important when it comes to accusing Leopold of the atrocities, as well as creating a greater notice to them.

Their intentions, as stated in the manifesto, to “secure just and humane treatment of the inhabitants of the Congo State, and restoration of the rights to the land and of their individual freedom”.[26] No more than a week later, the Massachusetts Commission for International Justice organized the American branch of the Congo Reform Association with members such as Mark Twain, Booker T. Washington, and W.E.B Dubois. The American CRA served the same purpose as the original CRA. It needed the American public to become aware of what was going on in the Congo and join to fight. The more people an organization has the greater the voice it carries.

Trying to achieve an international awareness also brought a greater difficulty to the task for which Morel set for himself. Morel knew the public would be swayed by hard evidence. Missionaries, high officials, and photos cannot be refuted due trustworthiness by the public. A religious cleric will generally not lie, especially about something so horrific; nor would a high governmental official. And photos are most undeniable proof that Morel used. That is why in February 1903, he published Roger Casement’s report on the Congo Free State. Morel used his connections in the press and had it published in major newspapers throughout Europe. He had it published in magazines and his own West African Mail. The constant use of undeniable evidence, such as missionary testimony, became the media catalyst that caused people to question Leopold’s constant denying of the situation.

In September 1904, Morel arrived in New York, for his American campaign, with a petition entitled “The Memorial”. The memorial contained signatures by all the members of the CRA. The purpose of the trip could be explained by Morel’s own words during an interview for the New York Herald in 1903. When asked by the interviewer “Why America?” Morel answered:

"America has a peculiar and vary clear responsibility in the matter, inasmuch as the American Government was the first to recognize the status of the International Association (later the Congo State), and thereby paved the way for similar action on the part of the European Powers… It is to be hoped that President Roosevelt and the American people may help undo the grieves wrong, which was thereby unknowingly inflicted upon the native inhabitants of the Congo territories."

Before Morel left for America he submitted a copy of the memorial to The New York Times, The New York Post, The Washington Post, The Boston Globe, and other Press syndicates. The CRA and Morel hoped that before his arrival that there would be a strong public support from the American citizens. All the newspapers covered his arrival and displayed excerpts of the memorial. By giving several articulate speeches throughout New England, Morel gained an audience from President Theodore Roosevelt, and gave the memorial with great enthusiasm. The New York Post covered the visit with a full page, two-column article. Americans citizens slowly started to gain a curiosity with Morel and the “Congo Question” because of the continuous newspaper articles about the campaign. On October 7 Morel gave a speech in Boston addressing the International Peace Congress. Like any of his writings, his speech was just as compelling and motivating, and became the form of media that caused the American public to focus their attention on the Congo.

"The errand which has brought me to the United States is a very simple on. It is to appeal to you on behalf of the oppressed and persecuted peoples of the Congo, for whose present unhappy condition you, in America, and we, in England, have a great moral responsibility, from which we cannot escape and from which in honour we should not attempt to escape… It is my privilege to ask you who are met here in the cause of peace whether you will not lead a helping hand in staying the cruel and destructive wars – if the murder of helpless men and women can be dignified by such a name… In appealing to you on behalf of those millions of helpless Africans… It is a great responsibility that you have. If our duty is clear, surely yours is also clear. The African slave trade has been revived, and is in full swing in the Congo today. I ask you to help us to root it up and fling it out of Africa, and just as I have no doubt of the greatness and loftiness of your ideals, so I have no doubt of what your answer will be."[28]

The American people only knew of Morel by newspaper articles. A public appearance offered the public to hear his words. The purpose of public speaking can range from simply transmitting information, to motivating people to act, to simply telling a story. Good orators should be able to change the emotions of their listeners, not just inform them. Public speaking can be a powerful tool to use for purposes such as motivation, influence, persuasion and informing a large group of people. Morel successfully utilized public speaking to rally the American people to push the Government.

It would take two more years for President Roosevelt and Congress to be convinced that they should get involved. Consequently another use of media convinced the United States Government. In a letter from President Roosevelt to Henry Cabot Lodge, Roosevelt writes: “The only tomfoolery that anyone seems bent on is that about the Congo Free State outrages, and that is imbecile rather than noxious.”[29] Overwhelmed by public pressure, Congress drafted a resolution, in 1906, on their position pertaining to the Congo Question. In this resolution they took the stance against Leopold and demanded he put a stop to the Congo Free State.

Leopold's Counter Campaign

Morel and others faced an able monarch, a man of great intellectual power, skilled in diplomacy, able to influence thousands of social, political, religious and economic channels, and the most influential being his propaganda machine that had influence over the Press. Leopold ordered counterattacks refuting all the claims that Morel made. He had his propaganda machine wrote articles to all major newspapers, one being the New York Times. During the summer of 1903 numerous letters to the editor, published in the same newspapers, defended Leopold and his Congo. None of the letters contained any evidence that backed up Leopold and refuted Morel’s claims.

Leopold took action which he hoped might alleviate the public anger against him. Earlier, he used tactics of discrediting Morel and the CRA, but these tactics had no effect. He advanced his Public Relations campaign against Morel. This time he did not use any letters, rather he just used a simple public relations tactic. He commissioned an internal investigation of the Congo to prove to the public that he cared. However, Leopold created a committee of Congo officials. In this committee he had his commissioners create reports that denied any “atrocities”. Morel planned for this to happen. During the investigation he had all the missionaries that he knew send him letters, photos, and testimony from the natives. All that he gathered would be used an extensive media blitz of pamphlets, newspaper articles, letters and books.

Leopold’s opposition utilized the greatest amount of media in 1904. Numerous pamphlets, letters, speeches, books and newspapers helped bring a larger focus to the Congo Question. Some of Leopold’s responses included articles in papers countering the claims, but it also should be noted that during much of Morel’s American visit Leopold dispatched agents to “spy” on Morel and to try to create distaste among the American people. These efforts failed fairly quickly as American, European newspaper editors liked Morel because of his journalistic background, and his writing sold newspapers. Leopold’s agents, as hard as they tried, could not sway the editors to stop running Morel’s articles.

While laying low in his own attacks, Leopold’s agents fought back the usual opposition articles. One instance came when Mark Twain released “King Leopold’s Soliloquy”, which talked about the abuses and Leopold’s denial. Twain wrote it from the perspective of Leopold. “They burst out and call me ‘the king with ten million murders on his soul’”[30] Throughout the book Twain positions the idea to his readers that Leopold is guilty and evil. “[Meditative pause] Well…not matter, I did beat the Yankees, anyway! There is comfort in that. [Reads with a mocking smile, the President’s Order of Recognition of April 22, 1884]” Twain’s description of Leopold’s actions create the visual of him plotting his scheme. This allowed Twain to cause the reader to stir up emotions against Leopold.

The agents countered it with letters to the editor refuting it, as well as creating a book entitled An Answer to Mark Twain. In the book they call Twain and Morel liars and manipulators. “Truth shines forth in the following pages, which summarily show what the Congo Free State is.” “All the Mr. Twain and Morel have said. Lies!”[31] However the agents spun their story, it did not have any effect on public opinion or focus. Protests still occurred in American and Europe as Morel kept writing. He continued to issue articles in the West African Mail as usual, which continued to expand public protest. Leopold, frustrated with the public, finally appointed a real commission of inquiry, unlike the previous commission where he just had fake reports written, to investigate specific charges of the atrocities and reported abuses. The commission included members of the Belgian Parliament and lower officials in the government.

The Downfall

Leopold released countless press statements about the commission in anticipation that it would quell the public uproar. However, the public did not know that Leopold wanted the findings to be private, and not published. Disappointingly to Leopold the commission stayed true to its task, and returned with some of the greatest evidence of abuse yet. The evidence consisted of interviews with over hundred natives and numerous missionaries, documents from the FP detailing deaths and mutilations inflicted, and documents from the Congo State administration proving that Leopold profited more than he reported.

The CRA retrieved the report through various sources, and the very information that Leopold did not want published appeared in The West African Mail, The New York Times, the Associated Press, and European Press Agencies. The report, “Evidence Laid Before the Congo Commission of Inquiry”, also became a pamphlet distributed by the CRA throughout Europe and the United States. A commission that appointed by Leopold himself reported back with horrific testimony, facts on deaths and mutilations, and letters obtained from the Congo Administration reveling that abuses were taking place. Leopold could not refute his own commission’s findings. As a result, in 1908, the Belgian Parliament discussed removing Leopold from power. However, before he could be removed, Leopold died a year later, thus ending the tyranny over the Congo State.

See also

- Congo Free State

- King Leopold II of Belgium

- Heart of Darkness

- E.D. Morel

- Roger Casement

- Congo Reform Association

- Propaganda

- Public Relations

- Public Diplomacy

- Political Warfare

References

- ^ In this time period the term “mass media” is to be understood as newspapers, magazines, pamphlets, letters, books, reports, speeches, and documents of which all are published for the viewing of the general public. During the 20th century, technology drove the growth of mass media which allowed the massive duplication of material. For Morel and others, the telegraph became the primary piece of technology to help advance their campaign.

- ^ Dunne, Kevin C. Imagining the Congo: The International Relations of Identity.[ New York: MacMillan, 2003] (pg 21)

- ^ Hochschild, Adam: King Leopold’s Ghost: A Story of Greed, Terror, and Heroism in Colonial Africa, Mariner Books, 1998. pp. 62. ISBN 0-330-49233-0.

- ^ Wack, Story of the Congo Free State , 19

- ^ Jesse Siddall Reeves. “The International Beginnings of the Congo Free State.” Johns Hopkins University Studies in Historical and Political Science 12, no. 11-12 (1894): pg 26

- ^ The Berlin Conference, The General Act of Feb 26, 1885. Chap I, VI.

- ^ George Washington Williams, “An Open Letter to His Serene Majesty Leopold II, King of the Belgians and Sovereign of the Independent State of the Congo” repr., John Hope Franklin, George Washington Williams: A Biography. [Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1985], 243-254.

- ^ Hochschild, Adam, King Leopold's Ghost, Pan Macmillan, London (1998). ISBN 0-330-49233-0.

- ^ The New York Times, April 15, 1891. pg 5

- ^ Jane Chapman. Comparative Media History: An introduction 1789-Present. [New York: Polity 2005] ( pg 67)

- ^ Hochschild, King Leopold’s Ghost, 186

- ^ E.D Morel. Trading Monopolies in West Africa. West African Mail. [Liverpool 1903] (pg 35)

- ^ E.D. Morel. The West African Mail. 1903

- ^ E.D. Morel. Trading Monopolies. 9-10

- ^ E.D. Morel. The Congo Horrors. [Liverpool: January 15, 1903.] (pg 5)

- ^ Red Rubber: The story of the rubber slave trade which flourished on the Congo for twenty years, 1890-1910 By E.D. Morel [1]

- ^ Affairs of West Africa By E.D. Morel: http://www.archive.org/details/affairsofwestafr00more

- ^ Sir Harry Johnston. A Book Review. The Daily Chronicle. [1903]

- ^ The Times [1903]

- ^ Cocks. The Story of the Congo Free State. 96

- ^ King Leopold's Rule in Africa by E.D. Morel: http://www.archive.org/details/kingleopoldsrule00moreuoft

- ^ Cocks. The Story of the Congo Free State. 106

- ^ E.D. Morel. King Leopold’s Rule of Africa. [ New York: Published by Funk and Wagnalls Company, 1905.] (pg 101)

- ^ Catherine Wynne. The Colonial Conan Doyle: British Imperialism, Irish Nationalism, and the Gothic. [London: Greenwood Publishing Group, 2002] (pg 26)

- ^ Catherine Wynne. The Colonial Conan Doyle: British Imperialism, Irish Nationalism, and the Gothic. [London: Greenwood Publishing Group, 2002] (pg 27)

- ^ Roger Casement. The Casement Report. pg 34

- ^ King Leopold's Soliloquy

- ^ The Boston Globe. Oct 7 1904.

- ^ Peter Diagn and L.H. Gann. The United States and Africa: A History. [Cambridge: University Press, 1987.] ( pg 195)

- ^ Mark Twain. King Leopold's Soliloquy: A Defense of His Congo Rule. [New York: P.R. Warren, 1905] pg 2

- ^ Anonymous. An Answer to Mark Twain. [New York : A&G Bulens Brothers, 1906.] (pg 2)

Bibliography

Primary

- Anonymous. An Answer to Mark Twain. New York : A&G Bulens Brothers, 1906.

- Boulger, Demetrius Charles de Kavanagh. The Congo State Is Not a Slave State; A Reply to Mr. E.D. Morel's Pamphlet Entitled "The Congo Slave State,". London: S. Low, Marston and Co, 1903. Google Digitized Books. (accessed March 3, 2008).

- Congo Reform Association. Evidence Laid Before the Congo Commission of Inquiry at Bwembu, Bolobo, Lulanga, Baringa, Bongandanga, Ikau, Bonginda, and Monsembe: Together with a Summary of Events (and Documents Connected Therewith) on the A.B.I.R. Concession Since the Commission Visited that Territory. University of California: Richardson & Sons, Printers, 1905.

- The Indictment Against the Congo Government. Liverpool Press, 1906.

- Morel, Edmund Dene. The Black Man's Burden: The White Man in Africa from the Fifteenth Century to World War I. New York: Monthly Review Press, 1969.

- The British Case in French Congo; The Story of a Great Injustice, Its Causes and Its Lessons. New York: Negro Universities Press, 1969.

- E. D. Morel's History of the Congo Reform Movement. Edited by Wm. Roger Louis and Jean Stengers. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1968.

- King Leopold’s Rule of Africa. New York: Published by Funk and Wagnalls Company, 1905.

- The Congo Horrors. Liverpool, England: Liverpool Press., January 15, 1903.

- The West African Mail. Liverpool, England: Liverpool Press.

- Twain, Mark. King Leopold's Soliloquy: A Defense of His Congo Rule. New York: P.R. Warren, 1905.

- Williams, George Washington. “An Open Letter to His Serene Majesty Leopold II, King of the Belgians and Sovereign of the Independent State of the Congo”. Reprinted in Franklin, John Hope. George Washington Williams: A Biography. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1985. 243-254.

Newspapers

- The New York Times

- The New York Herald

- The Boston Globe

- The Daily Chronicle

- The Morning Post

- The Times

- The West African Mail (The Organ of the Congo Reform Association)

Secondary

Monographs

- Anstey, Roger. King Leopold’s Legacy: The Congo Under Belgian Rule. 1908-1960. London: Oxford University Press, 1966.

- Bourne, H.R. Fox. Civilisation in Congoland: A Story of International Wrong Doing. London: P.S. King and Son, 1903.

- Chapman, Jane. Comparative Media History: An Introduction : 1789 to the Present. New York: Polity, 2005.

- Cline, Catherine Ann. E.D. Morel, 1873-1924: The Strategies of Protest. Dundonald, Belfast: Blackstaff, 1980.

- Cocks, Frederick Seymour. E. D. Morel, the Man and his Work. London: G. Allen & Unwin ltd., 1920.

- Conrad, Joseph. Heart of Darkness: A Case Study in Contemporary Criticism. Edited by Ross C. Murfin. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1989.

- Diagna, Peter and L.H. Gann. The United States and Africa: A History. Cambridge: University Press, 1987.

- Dunne, Kevin C. Imagining the Congo: The International Relations of Identity. New York: MacMillan, 2003

- Ewans, Martin. European Atrocity, African Catastrophe: Leopold II, the Congo Free State and Its Aftermath. London: Routledge Curzon, 2002.

- Franklin, John Hope. George Washington Williams: A Biography. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1985.

- Hochschild, Adam. King Leopold’s Ghost: A Story of Greed, Terror, and Heroism in Colonial Africa. New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1998.

- Robinson, Ronald. Africa and the Victorians: The Climax of Imperialism in the Dark Continent. New York: St. Martins Press, 1961.

- Singleton-Gates, Peter, Maurice Girodias, and Roger Casement. The Black Diaries: An Account of Roger Casement's Life and Times with a Collection of His Diaries and Public Writings. Paris: Olympia Press, 1959.

- Slade, Ruth M.. King Leopold's Congo: Aspects of the Development of Race Relations in the Congo Independent State. London: Oxford University Press, 1962.

- Taylor, A.J.P. The Trouble Makers: Dissent over Foreign Policy 1792-1939. London: Hamish Hamilton, 1957.

- Wack, Henry Wellington. The Story of the Congo Free State: Social, Political, and Economic Aspects of the Belgian System of Government in Central Africa. New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1905.

- Winks, Robin W., compiler. The Age of Imperialism. Englewood Cliffs, N.J: Prentice-Hall, 1969.

- Wynne, Catherine. The Colonial Conan Doyle: British Imperialism, Irish Nationalism, and the Gothic. London: Greenwood Publishing Group, 2002

Journals

- Anstey, Roger. "The Congo Rubber Atrocities -- A Case Study." African Historical Studies, no. 4 (1971): 59-76.

- Baylen, Joseph O.. "Senator John Tyler Morgan, E.D. Morel, and the Congo Reform Association." The Alabama Review, no. 15 (1962): 117-132.

- Harms, Robert. "The End of Red Rubber: A Reassessment." The Journal of African History, no. 16 (1975): 33-88.

- Reeves, Jesse Siddall. “The International Beginnings of the Congo Free State.” Johns Hopkins University Studies in Historical and Political Science 12, no. 11-12 (1894): 1-95.

External links

- The Crime of the Congo by Arthur Conan Doyle

- King Leopold's Rule in Africa by E.D. Morel

- Great Britain and the Congo, the pillage of the Congo basin by E.D. Morel

- The British case in French Congo; the story of a great injustice, its causes and its lessons by E.D. Morel

- A memorial on native rights in the land and its fruits in the Congo territories annexed by Belgium (subject to international recognition) in August, 1908

- The Present state of the Congo question : official correspondence between the Foreign Office and the Congo Reform Association (1912)

- Red rubber: the story of the rubber slave trade which flourished on the Congo for twenty years, 1890-1910 by E.D. Morel

- An Open Letter to King Leopold by George Washington Wililams

- A Report upon the Congo-State by George Washington Williams

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.