- Clarence W. W. Mayhew

-

Clarence William Whitehead Mayhew Born March 1, 1906[1]

ColoradoDied February 13, 1994[1]

San Rafael, CaliforniaNationality American Work Practice Clarence W.W. Mayhew, Architect Clarence William Whitehead Mayhew (March 1, 1906 – February 13, 1994) was an American architect best known as a designer of contemporary residential structures in the San Francisco Bay Area. Recognition came to him with a home designed in 1937 for the Manor family in Orinda, California; one which was included as an example of modern architecture's effect on the contemporary ranch house in California in several post-war published compilations of residential works.

Contents

Career

Mayhew took a job in San Francisco with well-known architect Arthur Brown Jr. sometime around 1922, working as a draftsman. Brown encouraged Mayhew to study at l'École des Beaux-Arts in Paris for two years; Mayhew finished in 1925. Returning to California, Mayhew obtained his architect degree from the University of California, Berkeley, in 1927.[2] Mayhew was subsequently hired by Miller and Pflueger and worked with that firm for six years during a time when they were designing prominent skyscrapers and movie palaces as well as taking occasional commissions for residential dwellings. In 1934 or 1935, Mayhew formed his own firm: Clarence W.W. Mayhew, Architect.[1]

Mayhew's influential Manor House was designed in 1937 for Marjorie and Harold V. Manor. Manor was a San Francisco native who married Marjorie W. Arnold in 1908.[3] He joined three different garden clubs including the California Horticultural Society.[4] The house that Mayhew designed for the Manors was basically a ranch house in structure, but light and airy with floor-to-ceiling windows and extensive skylights. It received notice across the country for its clean, light, asymmetrical lines and its embrace of both indoor and outdoor spaces. Its L-shaped plan echoed William Wurster's famous Gregory Farmhouse, and cost US$14,500 to build in 1938.[5] A series of publications made mention of the design—it appeared in House and Garden, Architect and Engineer,[6] Progressive Architecture,[7] Modern House in America,[8] Tomorrow's House[9] and If You Want to Build a House.[10] In 1974, architectural historian David Gebhard wrote of the design: "...California’s ability to wed indoors and outdoors was beautifully captured in the solarium, with its glass roof, sliding glass walls, and the adjacent sliding glass walls of the living room. This house was a realization of flexible indoor/outdoor space, so often discussed by the exponents of modernism but never achieved in such a lyric fashion."[2] Mayhew was quoted in Architectural Forum in 1939 as saying that "the house has a Japanese character in both plan and elevation. Although I did not copy any Japanese details, I did copy the underlying principle."[2]

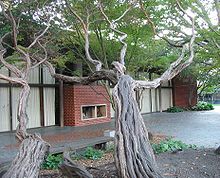

Mayhew's own home, carefully sited amid existing trees. Mayhew and Chermayeff designed a greater level of privacy on the street facing, saving expansive glass walls for the garden side

Mayhew's own home, carefully sited amid existing trees. Mayhew and Chermayeff designed a greater level of privacy on the street facing, saving expansive glass walls for the garden side

Mayhew designed his own house in collaboration with Serge Chermayeff, associate architect and employee of Mayhew's during 1940–1941 when Chermayeff was also teaching at California School of Fine Arts. Chermayeff was brought in so that Mayhew would not have his own wife for a client.[7] The house contrasted sharply with existing homes on Hampton Road, and appeared to be made of rectangular shapes descending the sloped property. The house divided into two functional groups, one for adults and one for children, with all living and sleeping rooms facing south. Glass walls were specified to allow maximum sunlight and viewing pleasure.[11] The two main structural units enclosed a private garden and were connected by a broad stairway enclosed against the weather, with the street side made of solid wood and the garden side fully glazed. The three children's rooms were separated with demountable hanging walls that could be changed to adapt to the family's needs. Author Alan Hess wrote in 2007 that the clean abstraction of the rectilinear blocks appeared to be based on Chermayeff's Bauhaus leanings but that the casual, site-specific interaction of garden, house and modernity showed the relaxation of California living apparent in Mayhew's prior work.[7]

A view of the outdoor terrace behind Mayhew's Alumni House at the University of California, Berkeley

A view of the outdoor terrace behind Mayhew's Alumni House at the University of California, Berkeley

Mayhew designed two alumni houses for local colleges. The Reinhardt Alumnae House was completed in 1949 for Mills College, and the Alumni House was finished in 1953 for the University of California, Berkeley. The latter structure, made for US$375,000[12] out of stone, brick, steel and glass[13] and organized into two wings in the International style,[14] was mentioned twice in Progressive Architecture, receiving notice in the Progressive Architecture Annual Design Survey for 1954 (Education).[15]

Social activities

Mayhew was an active member of the Bohemian Club and The Family. He served as "Father" at The Family and took part in the Bohemian Club's summer encampments at the Bohemian Grove where he directed the Lecture series for 20 years and was known as "Hap".[1] He volunteered with the props and sets department in at least one Grove Play: Birds of Rhiannon (1930)[16] and in 1969 he gave a Lakeside Talk.[17]

Mayhew was a board member of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and of the Talent Bank. He joined the St. Francis Yacht Club and the California Pioneers. Late in life, Mayhew developed Parkinson's disease.[1] He and his wife Joan Virginia Rapp Mayhew moved to San Rafael together. Mayhew died there in 1994; Joan died in 2005 at age 91, survived by their daughter, Joan Mayhew Beales.[18]

Works

- 1929 – Brat House, Friedman Residence, Woodside, California

- 1930–1931 – McGuire House Project, Wildwood Gardens, Piedmont, California

- 1935 – Edward G. Mayhew House, Oakland, California

- 1936 – Oakland House, Oakland, California

- 1937 – Manor House, Monte Vista, Orinda, California[19]

- 1937–1938 – Rowell House, Berkeley, California[20]

- 1938 – Morgan House, San Rafael, California

- 1938 – McHale House, Oakland, California

- 1939 – Sebree House, Berkeley, California

- 1941–1942 – Clarence W.W. Mayhew House, 330 Hampton Road, Piedmont, California

- 1941–1942 – St. Germain Avenue (Clarendon Heights View Home), San Francisco, California

- 1945–1946 – Shingle House, San Francisco, California

- 1947 – Hale House, Hillsborough, California[21]

- 1949 – Aurelia Henry Reinhardt Alumnae House, Mills College, Oakland, California[22]

- 1952–1953 – Alumni House, University of California, Berkeley

- 1952–1953 – Kaiser Foundation Medical Center, Walnut Creek, California

- Kaiser Permanente Hospital, Panorama City, California

- 1958 – Packard House, Los Altos Hills, California

- 1960 – Piedmont House, Piedmont, California

- 1961–1962 – Manning's Restaurant, Pasadena, California

- 1962–1964 – Manning's Cafeteria, Ballard, Seattle, Washington[2]

- 1964 – Steen Mansion, Washoe Valley, Nevada[2]

- Gates Rubber Company Building, Denver, Colorado

- Packard House, Big Sur, California

- Racetrack, Lima, Peru

References

- Notes

- ^ a b c d e ArchitectDB – architect record id 368: Clarence W. W. Mayhew

- ^ a b c d e City of Seattle. Historic & Cultural Resources Report. Manning’s Cafeteria/Ballard Denny’s. 5501 15th Avenue NW, Seattle, Washington. September 2007

- ^ San Francisco Call: p. 10. June 25, 1908. http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn85066387/1908-06-25/ed-1/seq-10/;words=Harold+Manor+V?date1=1836&rows=20&searchType=basic&state=&date2=1922&proxtext=harold+v.+manor&y=0&x=0&dateFilterType=yearRange&index=1.

- ^ Archive.org. Texts. Full text of "California garden societies and horticultural publications, 1947–1990 / 1990" UC Berkeley Oral History. 1989. Interview with F. Owen Pearce.

- ^ ArchitectDB – structure record id 10810: Manor, Harold V., House, Monte Vista, Orinda, CA

- ^ ArchitectDB – publication record id 7925: Recent Work of Clarence W.W. Mayhew, Architect, Residence of Harold V. Manor, Contra Costa County. July 1940.

- ^ a b c Hess, Alan (2007). Forgotten Modern: California Houses 1940–1970. Gibbs Smith. ISBN 1586858580. http://books.google.com/books?id=7jPzUoT2ssUC.

- ^ Ford, James; Katherine Morrow Ford (1940). Modern House in America. Architectural Book Publishing Company.

- ^ Archive.org. Full text of Tomorrow's House (1945) by George Nelson and Henry Wright

- ^ Mock, Elizabeth (1946). If You Want to Build a House. NYC Museum of Modern Art.

- ^ ArchitectDB – structure record id 10242: Mayhew, Clarence W.W., House, Piedmont

- ^ Berkeley Architectural Heritage Association. Verne A. Stadtman and the Centennial Publications Staff, UCB. Berkeley Buildings and Landmarks. (1967)

- ^ California Alumni Association. Rent Alumni House

- ^ Helfland, Harvey (2001). The Campus Guides: University of California Berkeley. Princeton Architectural Press. ISBN 1568982933. http://books.google.com/books?id=41A6PwEj4QgC.

- ^ ArchitectDB – publication record id 8123: P/A/ Annual Design Survey for 1954 Education

- ^ Young, Waldemar (1930). Birds of Rhiannon. http://books.google.com/books?id=I_j8fIS474IC.

- ^ Cross, Francis L. (1972). The Annals of the Bohemian Club for the years 1907–1972, Centennial Edition, volume V. San Francisco: Bohemian Club and Recorder-Sunset Press.

- ^ Stanford Alumni. May/June 2005. Class Notes. Obituaries: Joan Virginia Rapp Mayhew

- ^ Treib, Marc (1999). An Everyday Modernism: The Houses of William Wurster. University of California Press. ISBN 0520221710. http://books.google.com/books?id=yW-dd-xzXywC.

- ^ ArchitectDB – structure record id 10866: Rowell, Mr. and Mrs. Jonathan H., House, Berkeley, CA

- ^ Ford, Katherine Morrow (1951). The American House Today: 85 Notable Examples. Reinhold Publishing. pp. 128–129. http://www.archive.org/stream/americanhousetod00fordrich#page/128/mode/2up/.

- ^ Mills College. Administrative Offices. Reinhardt Alumnae House

External links

Media related to Clarence W. W. Mayhew at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Clarence W. W. Mayhew at Wikimedia Commons

Categories:- 1906 births

- 1994 deaths

- American architects

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.