- Peter Carl Fabergé

-

Peter Karl Fabergé also known as Karl Gustavovich Fabergé in Russia (Russian: Карл Густавович Фаберже, May 30, 1846 – September 24, 1920) was a Russian jeweller of Baltic German-Danish and French origin, best known for the famous Fabergé eggs, made in the style of genuine Easter eggs, but using precious metals and gemstones rather than more mundane materials.

Contents

Early life

He was born in Saint Petersburg, Russia to the jeweller Gustav Fabergé and his Danish wife Charlotte Jungstedt. Gustav Fabergé’s paternal ancestors were Huguenots, originally from La Bouteille, Picardy, who fled from France after the revocation of the Edict of Nantes, first to Germany near Berlin, then in 1800 to the Baltic province of Livonia, then part of Russia.

Initially educated in Saint Petersburg, Russia, in 1860 Gustav Fabergé, together with his wife and children retired to Dresden, leaving the business in the hands of capable and trusted managers. Peter Karl possibly undertook a course at the Dresden Arts and Crafts School. Two years later, Agathon, the Fabergé's second son was born. In 1864, Peter Karl embarked upon a "Grand Tour of Europe". He received tuition from respected goldsmiths in Germany, France and England, attended a course at Schloss’s Commercial College in Paris, and viewed the objects in the galleries of Europe’s leading museums. His travel and study continued until 1872, when at the age of 26 he returned to St. Petersburg and married Augusta Julia Jacobs. For the following 10 years, his father’s trusted workmaster Hiskias Pendin acts as his mentor and tutor. The company was also involved with cataloguing, repairing, and restoring objects in the Hermitage during the 1870s. In 1881 the business moved to larger street-level premises at 16/18 Bolshaya Morskaya.

Takes over the family business

Upon the death of Hiskias Pendin in 1882, Karl Fabergé took sole responsibility for running the company. Karl was awarded the title Master Goldsmith, which permitted him to use his own hallmark in addition to that of the firm. Karl Fabergé’s reputation was so high that the normal three-day examination was waived.[citation needed] His brother, Agathon, an extremely talented and creative designer, joined the business from Dresden; where he had also possibly studied at the Arts and Crafts School.[citation needed] Karl and Agathon were a sensation at the Pan-Russian Exhibition held in Moscow in 1882. Karl was awarded a gold medal and the St. Stanisias Medal. One of the Fabergé pieces displayed was a replica of a 4th century BC gold bangle from the Scythian Treasure in the Hermitage. The Tsar declared that he could not distinguish the Fabergé's work from the original and ordered that objects by the House of Fabergé should be displayed in the Hermitage as examples of superb contemporary Russian craftsmanship. The House of Fabergé with its range of jewels was now within the focus of Russia’s Imperial Court.

When Peter Karl took over the House, there was a move from producing jewellery in the then fashionable French 18th century style, to becoming artist-jewellers. This resulted in reviving the lost art of enamelling and concentrating on setting every single stone in a piece to its best advantage. Indeed, it was not unusual for Agathon to make ten or more wax models so that all possibilities could be exhausted before deciding on a final design. Shortly after Agathon joined the firm, the House introduced objects deluxe: gold bejewelled items embellished with enamel ranging from electric bell pushes to cigarette cases, including objects de fantaisie.

In 1885, Czar Alexander III gave the House of Fabergé the title; ‘Goldsmith by special appointment to the Imperial Crown’.

Easter eggs

The Czar also commissioned the company to make an Easter egg as a gift for his wife, the Empress Maria. The Czar placed an order for another egg the following year. However, from 1887, Carl Fabergé was apparently given complete freedom with regard to design, which then become more and more elaborate. According to the Fabergé Family tradition, not even the Tsar knew what form they would take: the only stipulation was that each one should contain a surprise. The next Czar, Nicholas II, ordered two eggs each year, one for his mother and one for his own wife, Alexandra. The tradition continued until the October Revolution.

Although the House of Fabergé is famed for its Imperial Easter eggs, it made many more objects ranging from silver tableware to fine jewelry. Fabergé’s company became the largest jewellery business in Russia. In addition to its Saint Petersburg head quarters, there were branches in Moscow, Odessa, Kiev and London. It produced some 150,000 to 200,000 objects from 1882 until 1917. In 1900 his work represented Russia at the 1900 World’s Fair in Paris. As Karl Fabergé was a member of the Jury, the House of Fabergé therefore exhibited hors concours (without competing). Nevertheless, the House was awarded a gold medal and the city’s jewellers recognised Karl Fabergé as maître. Additionally, Karl Fabergé was decorated with the most prestigious of French awards – he was appointed a Knight of the Legion of Honour. Two of Karl’s sons and his Head Workmaster were also honored. Commercially, the exposition was a great success and the firm acquired a great many orders and clients.

The main Fabergé store in Saint Petersburg was officially renamed Yakhont (Ruby) but still is known as the Fabergé store

The main Fabergé store in Saint Petersburg was officially renamed Yakhont (Ruby) but still is known as the Fabergé store

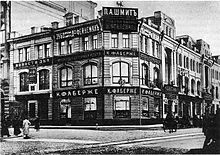

Shop of Faberge in the Moscow (Kuznetsky Most 4), 1893.

Shop of Faberge in the Moscow (Kuznetsky Most 4), 1893.

Stock, Russian Revolution and Nationalization

In 1916, the House of Fabergé became a joint-stock company with a capital of 3-million rubles.

The following year upon the outbreak of the October Revolution, the business was taken over by a 'Committee of the Employees of the Company K Fabergé. In 1918 The House of Fabergé was nationalised by the Bolsheviks. In early October the stock was confiscated. The House of Fabergé was no more.

After the nationalisation of the business, Karl Fabergé left St. Petersburg on the last diplomatic train for Riga. In mid-November, the Revolution having reached Latvia, he fled to Germany and first settled in Bad Homburg and then in Wiesbaden. Eugène, the Fabergé's eldest, travelled with his mother in darkness by sleigh and on foot through snow-covered woods and reached Finland in December 1918. During June 1920, Eugène reached Wiesbaden and accompanied his father to Switzerland where other members of the family had taken refuge at the Bellevue Hotel, in Pully near Lausanne. Peter Karl Fabergé never recovered from the shock of the Russian Revolution.[citation needed] In exile, the words always on his lips were, ‘This life is not worth living’.[citation needed] He died in Switzerland on September 24, 1920. His family believed he died of a broken heart.[citation needed] His wife Augusta died in 1925. The two were reunited in 1929 when Eugène Fabergé took his father’s ashes from Lausanne and buried them in his mother’s grave at the Cimetière du Grand Jas in Cannes, France.

Fabergé had four sons: Eugéne (1874–1960), Agathon (1876–1951), Alexander (1877–1952) and Nicholas (1884–1939). Descendants of Peter Karl Fabergé live in Europe, Scandinavia and South America.[citation needed]

Personal life

Henry Bainbridge, a manager of the London branch of the House of Fabergé recorded recollections of his meetings with his employer in both his autobiography[1] and the book he wrote about Fabergé.[2] We are also given an insight into the man from the recollections of François Birbaum, Fabergé’s senior master craftsman from 1893 until the House’s demise.[3]

From Bainbridge we know that while punctilious with his dress, Fabergé ‘rarely if ever wore black but favoured well-cut tweeds’. He added ‘There was an air of the country gentleman about him, at times he reminded one of an immaculate gamekeeper with large pockets.’ He was a very focused individual with no wasted actions or speech. He did not like small talk. On one occasion during dinner Bainbridge, feeling out of the conversation said, ‘I see Lord Swaythingly is dead’. Fabergé asked who he was and upon being told responded cuttingly, ‘And what can I do with a dead banker?’

When taking orders from customers he was always in a hurry and would soon forget the fine detail. He would then interrogate the staff so as to find who was standing near him who may have overheard. His great-granddaughter Tatiana Fabergé notes that he usually had a knotted handkerchief in his breast pocket.

When he noticed an unsuccessful article, he would call for his senior master craftsman and make endless derisory and ironical remarks. On occasions when Birbaum realised Fabergé was the designer, he would show him his sketch. Fabergé would then smile guiltily and say, ‘Since there is nobody to scold me, I have had to do it myself’. From Birbaum we also know that he was famous for his wit and was quite merciless to fops, whom he hated. A certain Prince who fell into this category boasted to Fabergé about his latest honour from the Czar adding that he had no idea as to why the award was made. Anticipating to be showered with congratulations from the jeweller, Fabergé simply replied, ‘Indeed, your Highness, I too have no idea what for’.

He never travelled with luggage, but bought all his requisites at his destination. On one occasion he arrived at the Negresco Hotel in Nice. The doorman barred his entrance because of this. Thankfully one of the Grand Dukes who was in residence called out a greeting and Karl Fabergé was ushered apologetically into the establishment.

Bainbridge concludes, ‘Taking him all in all, Fabergé came as near to a complete understanding of human nature as it is possible for a man to come, with one word only inscribed on his banner, and that word – tolerance. There is no doubt whatever that this consideration for the worth of others was the foundation for his success.’

References

- ^ Twice Seven: The Autobiography of H C Bainbridge (Routledge, London, 1933)

- ^ Fabergé: Goldsmith and Jeweller to the Imperial Court – His Life and Work (Batsford, London, 1949)

- ^ The History of the House of Fabergé according to the recollections of the senior master craftsman of the firm Franz P. Birbaum This was handwritten in 1919 at the request (or order) of the Soviet authorities. It added considerably to the knowledge of how the House of Fabergé operated. The English translation was published by Tatiana F Fabergé (great-granddaughter of Peter Karl Fabergé) and Valentin V. Skurlov in St. Petersburg in 1992.

- Tatiana Fabergé, Lynette G. Proler, Valentin V, Skurlov. The Fabergé Imperial Easter Eggs (London, Christie's 1997) ISBN 0-297-83565-3

- The History of the House of Fabergé according to the recollections of the senior master craftsman of the firm, Franz P. Birbaum (St Petersburg, Fabergé and Skurlov, 1992)

- Henry Charles Bainbridge. Peter Carl Fabergé – Goldsmith and Jeweller to the Russian Imperial Court – His Life and Work (London 1979, Batsfords – later reprints available such as New York, Crescent Books, 1979)

- A Kenneth Snowman The Art of Carl Fabergé (London, Faber & Faber, 1953–68)SBN 571 05113 8

- Geza von Habsburg Fabergé (Geneva, Habsburg, Feldman Editions, 1987) ISBN 0-89192-391-2

- Alexander von Solodkoff & others. Masterpieces from the House of Fabergé (New York, Harry N Abrahams, 1984) ISBN 0-8109-0933-2 * Géza von Habsburg Fabergé Treasures of Imperial Russia (Link of Times Foundation, 2004) ISBN5-9900284-1-5

- Toby Faber. Faberge's Eggs: The Extraordinary Story of the Masterpieces That Outlived an Empire (New York: Random House, 2008) ISBN 978-1-4000-6550-9

- Gerald Hill. Faberge and the Russian Master Goldsmiths (New York: Universe, 2007) ISBN 978-0-7893-9970-0

- A Kenneth Snowman, Carl Fabergé: Goldsmith to the Imperial Court of Russia (Random House, 1988), ISBN 0517405024

External links

- More facts from Faberge biography

- Empire of Eggs, Svetlana Graudt, Moscow Times, November 18, 2005

- Wartski London Historic Fabergé specialists

- A La Vieille Russie. New York. American Fabergé Specialists

- The House of Fabergé

- Current Fabergé Museum Exhibitions

- Picture gallery of private art collector

- Pallinghurst Resources LLP

- Objects of Fantasy – The World of Peter Carl Faberge Melissa Jellema. St. Xavier University. Chicago, IL. May 3, 2008

Categories:- 1846 births

- 1920 deaths

- Burials at the Cimetière du Grand Jas

- Fabergé family

- Russian artists

- Russian businesspeople

- Russian goldsmiths

- Russian inventors

- Russian jewellers

- Russian people of Danish descent

- Russian people of French descent

- People from Saint Petersburg

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.