- Coulomb blockade

-

In physics, a Coulomb blockade (abbreviated CB), named after Charles-Augustin de Coulomb's electrical force, is the increased resistance at small bias voltages of an electronic device comprising at least one low-capacitance tunnel junction. Because of the CB, the resistances of devices are not constant at low bias voltages, but increase to infinity for zero bias (i.e. no current flows).

Contents

Coulomb Blockade in a Tunnel Junction

A tunnel junction is, in its simplest form, a thin insulating barrier between two conducting electrodes. If the electrodes are superconducting, Cooper pairs (with a charge of two elementary charges) carry the current. In the case that the electrodes are normalconducting, i.e. neither superconducting nor semiconducting, electrons (with a charge of one elementary charge) carry the current. The following reasoning is for the case of tunnel junctions with an insulating barrier between two normal conducting electrodes (NIN junctions).

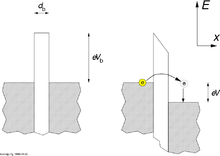

According to the laws of classical electrodynamics, no current can flow through an insulating barrier. According to the laws of quantum mechanics, however, there is a nonvanishing (larger than zero) probability for an electron on one side of the barrier to reach the other side (see quantum tunnelling). When a bias voltage is applied, this means that there will be a current, neglecting additional effects, the tunnelling current will be proportional to the bias voltage. In electrical terms, the tunnel junction behaves as a resistor with a constant resistance, also known as an ohmic resistor. The resistance depends exponentially on the barrier thickness. Typical barrier thicknesses are on the order of one to several nanometers.

An arrangement of two conductors with an insulating layer in between not only has a resistance, but also a finite capacitance. The insulator is also called dielectric in this context, the tunnel junction behaves as a capacitor.

Due to the discreteness of electrical charge, current through a tunnel junction is a series of events in which exactly one electron passes (tunnels) through the tunnel barrier (we neglect cotunneling, in which two electrons tunnel simultaneously). The tunnel junction capacitor is charged with one elementary charge by the tunnelling electron, causing a voltage buildup U = e / C, where e is the elementary charge of 1.6×10−19 coulomb and C the capacitance of the junction. If the capacitance is very small, the voltage buildup can be large enough to prevent another electron from tunnelling. The electrical current is then suppressed at low bias voltages and the resistance of the device is no longer constant. The increase of the differential resistance around zero bias is called the Coulomb blockade.

Observing the Coulomb Blockade

In order for the Coulomb blockade to be observable, the temperature has to be low enough so that the characteristic charging energy (the energy that is required to charge the junction with one elementary charge) is larger than the thermal energy of the charge carriers. For capacitances above 1 femtofarad (10−15 farad), this implies that the temperature has to be below about 1 kelvin. This temperature range is routinely reached for example by dilution refrigerators.

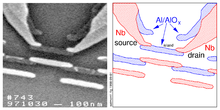

To make a tunnel junction in plate condenser geometry with a capacitance of 1 femtofarad, using an oxide layer of electric permittivity 10 and thickness one nanometer, one has to create electrodes with dimensions of approximately 100 by 100 nanometers. This range of dimensions is routinely reached for example by electron beam lithography and appropriate pattern transfer technologies, like the Niemeyer-Dolan technique, also known as shadow evaporation technique.

Another problem for the observation of the Coulomb blockade is the relatively large capacitance of the leads that connect the tunnel junction to the measurement electronics.

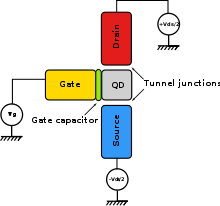

Single electron transistor

The simplest device in which the effect of Coulomb blockade can be observed is the so-called single electron transistor. It consists of two tunnel junctions sharing one common electrode with a low self-capacitance, known as the island. The electrical potential of the island can be tuned by a third electrode (the gate), capacitively coupled to the island.

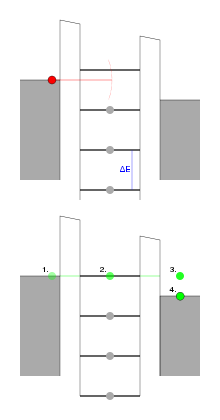

In the blocking state no accessible energy levels are within tunneling range of the electron (red) on the source contact. All energy levels on the island electrode with lower energies are occupied.

When a positive voltage is applied to the gate electrode the energy levels of the island electrode are lowered. The electron (green 1.) can tunnel onto the island (2.), occupying a previously vacant energy level. From there it can tunnel onto the drain electrode (3.) where it inelastically scatters and reaches the drain electrode Fermi level (4.).

The energy levels of the island electrode are evenly spaced with a separation of ΔE. ΔE is the energy needed to each subsequent electron to the island, which acts as a self-capacitance C. The lower C the bigger ΔE gets. To achieve the Coulomb blockade, three criteria have to be met:

- the bias voltage can't exceed the charging energy divided by the capacitance Vbias =

;

; - the thermal energy kBT must be below the charging energy EC =

, or else the electron will be able to pass the QD via thermal excitation; and

, or else the electron will be able to pass the QD via thermal excitation; and - the tunneling resistance (Rt) should be greater than

, which is derived from Heisenberg's Uncertainty principle.

, which is derived from Heisenberg's Uncertainty principle.

Coulomb Blockade Thermometer

A typical Coulomb Blockade Thermometer (CBT) is made from an array of metallic islands, connected to each other through a thin insulating layer. A tunnel junction forms between the islands, and as voltage is applied, electrons may tunnel across this junction. The tunneling rates and hence the conductance vary according to the charging energy of the islands as well as the thermal energy of the system.

Coulomb Blockade Thermometer is a primary thermometer based on electric conductance characteristics of tunnel junction arrays. The parameter V½=5.439NkBT/e, the full width at half minimum of the measured differential conductance dip over an array of N junctions together with the physical constants provide the absolute temperature.

Literature

- D.V. Averin and K.K Likharev Mesoscopic Phenomena in Solids, edited by B.L. Altshuler, P.A. Lee, and R.A. Webb (Elsevier, Amsterdam, 1991)

See also

External links

Categories: - the bias voltage can't exceed the charging energy divided by the capacitance Vbias =

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.