- Mexican redknee tarantula

-

Brachypelma smithi

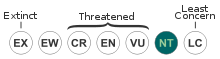

Mexican Red knee tarantula, female. Conservation status Scientific classification Kingdom: Animalia Phylum: Arthropoda Class: Arachnida Order: Araneae Family: Theraphosidae Genus: Brachypelma Species: B. smithi Binomial name Brachypelma smithi

F. O. Pickard-Cambridge, 1897Synonyms Eurypelma smithi Euathlus smithi

The Brachypelma smithi (also called Mexican Red-kneed Tarantula), is a terrestrial tarantula native to the western faces of the Sierra Madre Occidental and Sierra Madre del Sur mountain ranges in Mexico. They are a large species, of which are a popular choice for enthusiasts. Like most Tarantulas, they are very long lived

Contents

Description

The mature Brachypelma Smithi has a dark-colored body with orange patches on the joints of its legs, the second element of the legs (the trochanter) is orange-red. Following molting, the colors are more pronounced. The dark portion is very black while the orange-red portions will be far more on the reddish side.

An adult female has a body roughly 4 inches long, with a leg span of 6 inches, and a mass of approximately 15 grams. Both sexes are similar in appearance, with the male having a somewhat smaller body, but longer legs. Thus the male is of comparable size to the female, but has a significantly smaller mass.

Longevity

They grow very slowly and mature relatively late. The Mexican Red-kneed Tarantula can live between 20 - 30 years.

Molting

Like all tarantulas, the Mexican Red Leg, a mygalomorph,[1] must go through a moulting process in order to grow. It is an essential part of their life process. Moulting serves several purposes, such as renewing the tarantula’s outer cover (shell) and replacing missing appendages. As your tarantula grows it will regularly moult (shed its skin), 2-3 times a year in the case of the half grown individual.[2] Since the exoskeleton cannot stretch, it has to be replaced by a new one from beneath. A mygalomorph may also regenerate lost appendages gradually, with each succeeding moult. Previous to moulting the spider will become sluggish and stop eating in order to conserve as much energy as possible. It is vitally important that the tarantula not be disturbed during this period, for shedding is a stressful activity that consumes every ounce of its energy[3] and can be fatal in later years. Their abdomens will lose hair, darken and look swollen. This is actually the new exoskeleton beneath. Normally the spider will turn on its back to moult and lie still in that position for several hours. Once this has been accomplished, the tarantula will not eat for two or more days, as its fangs are still soft: the fangs are also part of the exoskeleton and are shed with the rest of the skin.[4] The whole process takes less than 24 hours and leaves the tarantula with a shiny, moist new skin in place of an old, faded one.

Behavior

Like most New World tarantulas, they will kick urticating hairs from their abdomens and their back legs if disturbed, rather than bite. They are not venomous to humans and are considered extremely docile, though, as with all Tarantulas, allergies may intensify with any bite.[5]

They carve deep burrows into soil banks, which keeps them protected from predators, like the White-nosed Coati, and enables them to ambush passing prey. The females will spend the majority of their lives in their burrows. The burrows are typically located in or not far from vegetation and consists of a single entrance with a tunnel leading to one or two chambers. The entrance is just slightly larger than the body size of the spider. The tunnel, usually about three times the tarantula's leg span in length, leads to a chamber which is large enough for the spider to safely molt in. Further down the burrow, via a shorter tunnel, a larger chamber is located where the spider will rest and eat its prey. When the tarantula needs privacy, e.g. when molting or laying eggs, the entrance is sealed with silk sometimes supplemented with soil and leaves.[6]

Habitat

Their natural habitat is in deciduous tropical forests in the hilly southwestern Mexico, especially in Colima and Guerrero.[5][6] In 1985 the species were listed as endangered by CITES because the wild-caught specimens shipped for the pet market were decreasing in size. The smaller sizes were suspected to be a consequence of a declining population due to excessive export. The export is not the only threat however; some local people have reportedly made a habit of killing these spiders in a nearly systematic way using pesticides, pouring gasoline into burrows or simply killing migrating spiders on sight.[5] The causes of these actions seem to be an irrational fear based on myth surrounding B. smithi and related species[7][5]. Thus, whether the listing strengthened the B. smithi wild population or not remains uncertain. The species has nonetheless been bred successfully in captivity, making them readily available on the pet market despite almost no export of wild-caught spiders from Mexico.[5]

References

- ^ http://bugguide.net/node/view/46198

- ^ http://www.earthlife.net/chelicerata/tarantula.html

- ^ http://www.eightlegs.org/general/molt.html

- ^ http://arachnophiliac.info/burrow/btstalk.htm

- ^ a b c d e Stanley A. Schultz, Marguerite J. Schultz. The Tarantula Keeper's Guide: Comprehensive Information on Care, Housing, and Feeding (Revised Edition). Barrons (2009).

- ^ a b A. Locht, M. Yanez and I. Vazquez. Distribution and Natural History of Mexican Species of Brachypelma and Brachypelmides. Journal of Arachnology (1999).

- ^ http://www.minaxtarantulas.se/articles/brachypelma-smithi-cambridge-1897/

External links

- Caring for a Mexican Redknee Tarantula

- Brachypelma smithi and photos of next 14 Brachypelma sp. in tarantulas gallery.

Categories:- IUCN Red List near threatened species

- Theraphosidae

- Endemic fauna of Mexico

- Spiders of North America

- Fauna of Mexico

- Sierra Madre Occidental

- Animals described in 1897

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.