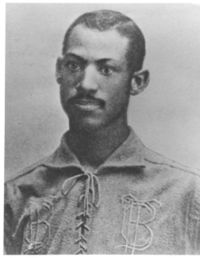

- Moses Fleetwood Walker

-

Moses Fleetwood Walker

Catcher Born: October 7, 1856

Mount Pleasant, OhioDied: May 11, 1924 (aged 67)

Cleveland, OhioBatted: Right Threw: Right MLB debut May 1, 1884 for the Toledo Blue Stockings Last MLB appearance September 4, 1884 for the Toledo Blue Stockings Career statistics Games played 42 Runs 23 Batting average .261 Teams Moses Fleetwood Walker [″Fleet″] (October 7, 1857 – May 11, 1924) was an American Major League Baseball player and author who is credited with being the first African American to play professional baseball.[1]

Contents

Baseball career

Walker was born in Mount Pleasant, Ohio, the son of Dr. Moses W. Walker, the first African-American physician in Mount Pleasant, and his mother, a white woman. During his childhood, his family moved from Mount Pleasant, to Steubenville. Walker was educated in the black schools, until the schools in Steubenville were integrated. Both Moses and his brother Welday attended Steubenville High School. He enrolled in Oberlin College in 1878 and played on the college's first varsity baseball team in the spring of 1881. Walker was an amazing athlete, and was a star catcher for Oberlin.[2]

He was recruited by the University of Michigan and played varsity baseball for Michigan in 1882. On March 4, 1882, the University of Michigan student newspaper, The Chronicle, reported: "M.F. Walker, of the class of '83 at Oberlin, arrived in town last week, and intends to enter the University. Mr. Walker caught for the Oberlin baseball team, and last year corresponded with the manager of the Bostons with a view to traveling with the latter nine during the summer, but at length concluded not to do so. Packard and Walker will form the battery for '83's nine this spring."[3]

While attending Michigan, Walker was able to play for the White Sewing Machine Club, based in Cleveland, Ohio.[2] It was here that the young Walker experienced his first mistreatment based on his skin color. While the players dined at the St. Cloud Hotel in Kentucky, Walker was refused service because he was black. Things would get worse when the game was played, as the opposing team refused to take the field when Walker was installed at catcher. Walker was pulled, but his replacement was a mediocre player who could not handle the pitches thrown to him. When the crowd began to chant for Walker to play, the opposing team's owner begrudgingly allowed the Cleveland team to insert Walker.[2]

The school had a terrible 1881 season, with catching being the sore part of the team. It was so terrible, that Michigan would recruit semi-pro players to play catcher for the bigger games. In 1882, Walker had an amazing season for Michigan. In 1882, Michigan went 10-3, with Walker batting second in the lineup. For the year, Walker is credited as batting .308 for the season.[2]

Walker signed with the minor league team, the Toledo Blue Stockings of the Northwestern League in 1883. At the time few catchers wore any equipment, including gloves. Walker had his first encounter with Cap Anson that year, when Toledo played an exhibition game against the Chicago White Stockings on August 10. Anson refused to play with Walker on the field. However, Anson did not know that on that day Walker was slated to have a rest day. Manager Charlie Morton played Walker, and told Anson the White Stockings would forfeit the gate receipts if they refused to play. Anson then agreed to play.[4]

In 1884 Toledo joined the American Association, which was a Major League at that time in competition with the National League. Walker made his Major League debut on May 1 against the Louisville Eclipse. In his debut, he went hitless and had four errors.[1] In forty two games, Walker had a batting average of .263. His brother, Welday Walker, later joined him on the team, playing in six games. The Walker brothers are the first known African Americans to play baseball in the Major Leagues.

Walker struggled at first with the bat, but was well regarded for having a rocket for an arm. In 1884, he batted .264, which was well above the league average. A testament to how good Walker was, his back-up was a player named Deacon McGwire, who would go on to a 26 year career, catching 1,600 games.

Walker's teammate and star pitcher, Tony Mullane, stated Walker "was the best catcher I ever worked with, but I disliked a Negro and whenever I had to pitch to him I used to pitch anything I wanted without looking at his signals."[5] Mullane's view hurt the team, as there were a number of passed balls and several injuries suffered by Walker, including a broken rib.[2] There were games where Walker was so hurt, he could only play in the outfield.

Walker suffered a season-ending injury in July, and Toledo folded at the end of the year. Walker returned to the minor leagues in 1885, and played in the Western League for Cleveland, which folded in June. He then played for Waterbury in the Eastern League though 1886.

In 1887 Walker moved to the International League's Newark Little Giants. He caught for star pitcher George Stovey, forming the first known African-American battery. On July 14, the Chicago White Stockings played an exhibition game against the Little Giants. Contrary to some modern-day writers, Anson did not have a second encounter with Walker that day (Walker was apparently injured, having last played on July 11, and did not play again until July 26). But Stovey had been listed as the game's scheduled starting pitcher, in the Newark News of July 14. Only days after the game was it reported (in the Newark Sunday Call) that, "Stovey was expected to pitch in the Chicago game. It was announced on the ground [i.e. "at the ballpark"] that he was sulking, but it has since been given out that Anson objected to a colored man playing. If this be true, and the crowd had known it, Mr. Anson would have received hisses instead of the applause that was given him when he first stepped to the bat." On the morning of that same, International League owners had voted 6-to-4 to exclude African-American players from future contracts.[6]

In the off-season, the International League modified its ban on black players, and Walker signed with the Syracuse, New York franchise for 1888. In September 1888, Walker did have his second incident with Anson. When Chicago was at Syracuse for an exhibition game, Anson refused to start the game when he saw Walker's name on the scorecard as catcher. "Big Anson at once refused to play the game with Walker behind the bat on account of the Star catcher’s color," the Syracuse Herald said. Syracuse relented and someone else did the catching.[7]

Walker remained in Syracuse until the team released him in July 1889.

Shortly thereafter, the American Association and the National League both unofficially banned African-American players, making the adoption of Jim Crow in baseball complete. Baseball would remain segregated until 1946 when Jackie Robinson "broke the color barrier" in professional baseball playing for the Brooklyn Dodgers' minor league affiliate in Montreal.

Life after baseball

In 1891, Walker was out of professional baseball, but he was not suffering not playing the game. Walker purchased the Union Hotel in Steubenville. Seeing that moving pictures could be very popular, Walker bought a theater in near by Cadiz. Walker applied for patents on several inventions for moving-picture equipment and even published a weekly newspaper.[8]

Walker was attacked by a group of white men in Syracuse, New York in April 1891. He stabbed and killed a man named Patrick Murray during the attack. The Sporting Life reported "Walker drew a knife and made a stroke at his assailant. The knife entered Murray's groin, inflicting a fatal wound. Murray's friends started after Walker with shouts of 'Kill him! Kill him!' He escaped but was captured by the police, and [was] locked up."[9]

Walker was charged with second-degree murder and claimed self-defense. He was acquitted of all charges on June 3, 1891. Adding to the weight of the verdict, was that Walker was acquitted by an all white jury.[8] The Cleveland Gazette reported "When the verdict was announced the court house was thronged with spectators, who received it with a tremendous roar of cheers... Walker is the hero of the hour."[10]

Also in 1891, Walker received patents for an exploding artillery shell.[11]

Walker became a supporter of Black nationalism and came to believe racial integration would fail in the United States. In 1908 he published a 47-page pamphlet titled Our Home Colony: A Treatise on the Past, Present, and Future of the Negro Race in America. In that pamphlet he recommended African Americans emigrate to Africa: "the only practical and permanent solution of the present and future race troubles in the United States is entire separation by emigration of the Negro from America."[12] He warned "The Negro race will be a menace and the source of discontent as long as it remains in large numbers in the United States. The time is growing very near when the whites of the United States must either settle this problem by deportation, or else be willing to accept a reign of terror such as the world has never seen in a civilized country."[9]

He died May 11, 1924 in Cleveland, Ohio, and is interred at Union Cemetery in Steubenville, Ohio.

Baseball history

Walker has traditionally been credited as the first African-American major league player. Research in the early 21st century by the Society for American Baseball Research indicates William Edward White, who played one game for the Providence Grays in 1879, may have been the first.[13]

William Edward White was the son of a white former slaveholder from Georgia and his mixed-race mistress. White attended college at Brown University where he also played varsity baseball. He filled in for one game for the Grays on June 21 when the Providence team was short-handed.

It is unclear, however, if White's contemporaries in Rhode Island knew of his racial background. White's race is never mentioned in any accounts of his baseball exploits at Brown or with Providence. Furthermore, the 1880 census, as well as several later censuses, indicate his race as "white".[14] He may have been passing as a white man during his time in Rhode Island.[citation needed]

References

- ^ a b Crazy ’08: How a cast of Cranks, Rogues, Boneheads and Magnates created the Greatest Year in Baseball History, p. 168, by Cait Murphy, Smithsonian Books, a Division of Harper Collins, 2007, ISBN 978-0-06-088937-1

- ^ a b c d e http://www.jockbio.com/Classic/Walker/Walker_bio.html

- ^ "untitled". The Chronicle: p. 154. 1882-03-04. http://books.google.com/books?id=MEjiAAAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_v2_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false.

- ^ Cap Chronicled, Chapter 4: Cap's Great Shame - Racial Intolerance

- ^ Baseball Library entry for Moses Fleetwood Walker

- ^ Howard W. Rosenberg, Cap Anson 4: Bigger Than Babe Ruth: Captain Anson of Chicago, page 430, and Cap Chronicled, Chapter 4: Cap's Great Shame - Racial Intolerance

- ^ Rosenberg, Cap Anson 4, page 434

- ^ a b http://www.oberlin.edu/external/EOG/OYTT-images/MFWalker.html-0

- ^ a b Michigan Daily Online article 'A Fleeting ambition'

- ^ Cleveland Gazette article from The Ohio Historical Society's "The African American Experience in Ohio, 1850-1920"

- ^ Harrison County, Ohio Heritage/History page

- ^ Walker, Moses Fleetwood biography

- ^ Associated Press via ESPN.com: "Was William Edward White Really First?" (unbylined) Friday, January 30, 2004

- ^ Malinowski, W. Zachary. "Who was the First Black Man to Play in the Major Leagues?" The Providence Journal, 15 February 2004

External links

- Career statistics and player information from Baseball-Reference, or Baseball-Reference (Minors)

- Negro League Baseball Players Association

- Baseball Hall of Fame

- BaseballLibrary.com

Additional reading

- David W. Zang, Fleet Walker's Divided Heart (Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 1995).

- Howard W. Rosenberg, Cap Anson 4: Bigger Than Babe Ruth: Captain Anson of Chicago (Arlington, Virginia: Tile Books, 2006).

Categories:- 1856 births

- 1924 deaths

- Major League Baseball catchers

- 19th-century baseball players

- Toledo Blue Stockings players

- University of Michigan alumni

- Baseball players from Ohio

- African American baseball players

- Oberlin College alumni

- People from Jefferson County, Ohio

- People from Steubenville, Ohio

- People acquitted of murder

- Toledo Blue Stockings (minor league) players

- Waterbury (minor league baseball) players

- Cleveland Forest Cities players

- Waterbury Brassmen players

- Newark Little Giants players

- Syracuse Stars (minor league) players

- Oconto (minor league baseball) players

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.