- Ecdysis

-

Ecdysis (from Ancient Greek: ἐκδύω – ekduo – to take off, strip off[1]) is the moulting of the cuticula in many invertebrates. This process of moulting is the defining feature of the clade Ecdysozoa,[2] comprising the arthropods, nematodes, velvet worms, horsehair worms, rotifers, tardigrades and Cephalorhyncha.[3] Since the cuticula of these animals often forms an inelastic exoskeleton, it is shed during growth and a new, larger covering is formed.[2] The remnants of the old, empty exoskeleton are called exuviae.[3]

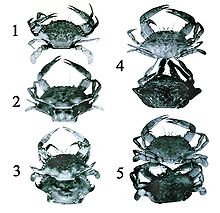

After moulting, an arthropod is described as teneral, a callow; it is "fresh", pale and soft-bodied. Within one or two hours, the cuticle hardens and darkens following a tanning process similar to that of the tanning of leather.[4] It is during this short phase that the animal expands, since growth is otherwise constrained by the rigidity of the exoskeleton. Growth of the limbs and other parts normally covered by hard exoskeleton is achieved by transfer of body fluids from soft parts before the new skin hardens. A spider with a small abdomen may be undernourished but more probably has recently undergone ecdysis. Some arthropods however, especially large insects with tracheal respiration, expand their new exoskeleton by swallowing or otherwise taking in air. The maturation of the structure and coloration of the new exoskeleton might take days or weeks in a long-lived insect; this can raise problems in trying to identify the species when a specimen has just recently undergone ecdysis.

Ecdysis may also enable damaged tissue and missing limbs to be regenerated or substantially re-formed, although this may only be complete over a series of moults, the stump being a little larger with each moult until it is of normal, or near normal size again.[5]

Contents

Process

In preparation for ecdysis, the arthropod becomes inactive for a period of time, undergoing apolysis (separation of the old exoskeleton from the underlying epidermal cells). For most organisms, the resting period is a stage of preparation during which the secretion of fluid from the moulting glands of the epidermal layer and the loosening of the underpart of the cuticle occur. Once the old cuticle has separated from the epidermis, the digesting fluid is secreted into the space in between them. However, this fluid remains inactive until the upper part of the new cuticle has been formed. Then, by crawling movements, the pharate animal pushes forward in the old integumentary shell, which splits down the back allowing the animal to emerge. Often, this initial crack is caused by an increase in blood pressure within the body (in combination with movement), forcing an expansion across its exoskeleton, leading to an eventual crack that allows for certain organisms such as spiders to extricate themselves. While the old cuticle is being digested, the new layer is secreted. All cuticular structures are shed at ecdysis, including the inner parts of the exoskeleton, which includes terminal linings of the alimentary tract and of the tracheae if they are present.

Insects

This beetle (Harmonia axyridis) has recently eclosed. The pupal exuviae are in the background, head down, the attitude favourable for ecdysis. Its wings have filled out, but it is still a callow. It has turned head up so that its wings can dangle and thus harden in the correct form.

This beetle (Harmonia axyridis) has recently eclosed. The pupal exuviae are in the background, head down, the attitude favourable for ecdysis. Its wings have filled out, but it is still a callow. It has turned head up so that its wings can dangle and thus harden in the correct form.

Each stage in the development of an insect between moults is called an instar, or stadium. Endopterygota tend to have few instars (4-5), while other insects such as Exopterygota can have anywhere up to 15. Endopterygota insects have more alternatives to moulting, such as expansion of the cuticle and collapse of air sacs to allow growth of internal organs.

The process of moulting in insects begins with the separation of the cuticle from the underlying epidermal cells (apolysis) and ends with the shedding of the old cuticle (ecdysis). In many of them it is initiated by an increase in the hormone ecdysone. This hormone causes:

- apolysis – the separation of the cuticle from the epidermis

- secretion of new cuticle materials beneath the old

- degradation of the old cuticle

After apolysis, moulting fluid is secreted into the space between the old cuticle and the epidermis (the exuvial space), this contains inactive enzymes which are activated only after the new epicuticle is secreted. This prevents them from digesting the new procuticle as it is laid down. The lower regions of the old cuticle – the endocuticle and mesocuticle – are then digested by the enzymes and subsequently absorbed. The exocuticle and epicuticle resist digestion and are hence shed at ecdysis.

Spiders

Female Synema decens crab spider, teneral after final ecdysis, still dangling from drop line, about to be mated, opisthosoma still shrunken.

Female Synema decens crab spider, teneral after final ecdysis, still dangling from drop line, about to be mated, opisthosoma still shrunken.

Spiders generally change their skin for the first time while still inside the egg sac, and the spiderling that emerges generally looks fairly recognisably like the adult. However, there may be confusion in trying to identify the species if one does not realise that it is a juvenile one is working with. Even if one does know this, it may not be possible to identify it with any confidence, since most keys refer to adult characters.

The number of moults varies, both between species and genders, but generally will be between five times and nine times before the spider reaches maturity. Not surprisingly, males generally being smaller than females, the males of many species mature faster and do not undergo ecdysis as many times as the females before maturing.

Members of the Mygalomorphae generally are very long-lived, sometimes 20 years or more, and typically they moult annually even after they mature.

Spiders stop feeding some time before moulting, usually several days. The physiological processes of releasing the old exoskeleton from the tissues beneath typically cause various colour changes, such as darkening. If the old exoskeleton is not too thick it also may be possible to see new structures, such as setae, from outside. However, nervous contact with the old exoskeleton is maintained till a very late stage in the process.

Commonly the new, teneral exoskeleton is wrinkled because it has to accommodate a larger frame than the previous instar, while fitting into the previous exoskeleton until it has been shed.

Most species of spiders hang from silk during the entire process, either dangling from a drop line, or fastening their claws into webbed fibres attached to a suitable base. The discarded, dried exoskeleton typically remains hanging where it was abandoned once the spider has left.

To open the old exoskeleton, the spider generally contracts its abdomen (opisthosoma) to supply enough fluid to pump into the prosoma with sufficient pressure to crack it open along its lines of weakness. The carapace lifts off from the front, like a helmet, as its surrounding skin ruptures, but it remains attached at the back. Now the spider works its limbs free and typically winds up dangling by a new thread of silk attached to its own exuviae, which in turn hang from the original silk attachment.

At this point the spider is a callow; it is teneral and vulnerable. As it dangles, its exoskeleton hardens and takes shape. The process may take minutes in small spiders, or some hours in the larger Mygalomorphs. Some spiders, such as some Synema species, members of the Thomisidae (crab spiders) mate while the female is still callow, during which time she is unable to eat the male.[6]

Eurypterids

Eurypterids are a group of chelicerates that became extinct in the late Permian. They underwent ecdysis in a similar manner to extant chelicerates, and most fossils are thought to be of exuviae, rather than cadavers.[3]

References

- ^ Liddell & Scott (1889). An Intermediate Greek-English Lexicon. Oxford: Clarendon Press. http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.04.0058%3Aentry%3De)kdu%2Fw.

- ^ a b John Ewer (2005). "How the ecdysozoan changed its coat". PLoS Biology 3 (10): e349. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0030349. PMC 1250302. PMID 16207077. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=1250302.

- ^ a b c O. Erik Tetlie, Danita S. Brandt & Derek E. G. Briggs (2008). "Ecdysis in sea scorpions (Chelicerata: Eurypterida)". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 265: 182–194. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2008.05.008.

- ^ Russell Jurenka (2007). "Insect physiology". In Sybil P. Parker. McGraw-Hill Encyclopedia of Science & Technology. 9 (10th ed.). p. 323. ISBN 978-0-07-144143-8.

- ^ Penny M. Hopkins (2001). "Limb regeneration in the fiddler crab, Uca pugilator: hormonal and growth factor control". American Zoologist 41 (3): 389–398. doi:10.1093/icb/41.3.389.

- ^ Erik Holm & Anna Sophia Dippenaar-Schoeman (2010). Goggo Guide: the Arthropods of Southern Africa. LAPA. ISBN 978-0-7993-4689-3.

External links

Media related to Ecdysis at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Ecdysis at Wikimedia Commons

Categories:- Developmental biology

- Arthropod anatomy

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.