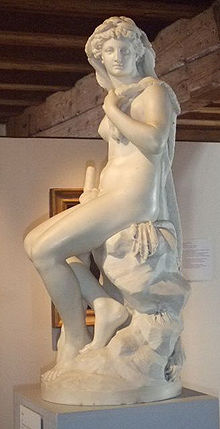

- Omphale

-

- For the city in Sicily, formerly called Omphale, see Daedalium.

In Greek mythology, Omphale (Ancient Greek: Ὀμφάλη) was a daughter of Iardanus, either a king of Lydia, or a river-god. Omphale was queen of the kingdom of Lydia in Asia Minor; according to Bibliotheke[1] she was the wife of Tmolus, the oak-clad mountain king of Lydia; after he was gored to death by a bull, she continued to reign on her own.

Diodorus Siculus provides the first appearance of the Omphale theme in literature, though Aeschylus was aware of the episode.[2] The Greeks did not recognize her as a goddess: the undisputed etymological connection with omphalos, the world-navel, has never been made clear.[3] In her best-known myth, she is the master of the hero Heracles during a year of required servitude, a scenario that offered writers and artists opportunities to explore gender roles and erotic themes.

Contents

Heracles and Omphale

In one of many Greek variations on the theme of penalty for "inadvertent" murder, for his murder of Iphitus, the great hero Heracles, whom the Romans identified as Hercules, was, by the command of the Delphic Oracle Xenoclea, remanded as a slave to Omphale for the period of a year,[4] the compensation to be paid to Eurytus, who refused it.[5] The theme, inherently a comic inversion of gender roles, was not illustrated in Classical Greece. Plutarch, in his vita of Pericles, 24, mentions lost comedies of Kratinos and Eupolis, which alluded to the contemporary capacity of Aspasia in the household of Pericles.[6] and to Sophocles in The Trachiniae it was shameful for Heracles to serve an Oriental woman in this fashion,[7] but there are many late Hellenistic and Roman references in texts and art to Heracles being forced to do women's work and even wear women's clothing and hold a basket of wool while Omphale and her maidens did their spinning, as Ovid tells:[8] Omphale even wore the skin of the Nemean Lion and carried Heracles' olive-wood club. Unfortunately no full early account survives, to supplement the later vase-paintings.

But it was also during his stay in Lydia that Heracles captured the city of the Itones and enslaved them, killed Syleus who forced passersby to hoe his vineyard, and captured the Cercopes. He buried the body of Icarus and took part in the Calydonian Boar Hunt and the Argonautica.

After some time, Omphale freed Heracles and took him as her husband.

Omphale's name, connected with omphalos, a Greek word meaning navel (or axis), may represent a significant Lydian earth goddess. Heracles's servitude, a mystical marriage, thus may represent the servitude of the sun to the axis of the celestial sphere, the spinners being Lydian versions of the Moirae. Most earth goddess religions contained a priesthood which wore women's clothing, was effeminate, or involved eunuchs. The priest of Heracles, curiously, also wore female clothing, and this myth may represent an attempt to explain the fact.

Sons of Heracles in Lydia

Diodorus Siculus (4.31.8) and Ovid in his Heroides (9.54) mention a son named Lamos. But Apollodorus (2.7.8) gives the name of the son of Heracles and Omphale as Agelaus.

Pausanias (2.21.3) gives yet another name, mentioning Tyrsenus, son of Heracles by "the Lydian woman", by whom Pausanias presumably means Omphale. This Tyrsenus supposedly first invented the trumpet, and Tyrsenus' son Hegeleus taught the Dorians with Temenus how to play the trumpet and first gave to Athena the surname Trumpet.

The name Tyrsenus appears elsewhere as a variant of Tyrrhenus, whom many accounts bring from Lydia to settle the Tyrsenoi/Tyrrhenians/Etruscans in Italy. Dionysius of Halicarnassus (1.28.1) cites a tradition that the supposed founder of the Etruscan settlements was Tyrrhenus, the son of Heracles by Omphale the Lydian, who drove the Pelasgians out of Italy from the cities north of the Tiber river. Dionysius gives this as an alternate to other versions of Tyrrhenus' ancestry.

Herodotus (1.7) refers to a Heraclid dynasty of kings who ruled Lydia, yet were perhaps not descended from Omphale, writing, "The Heraclides, descended from Heracles and the slave-girl of Iardanus...." Omphale as slave-girl seems odd. However, Diodorus Siculus relates that when Heracles was still Omphale's slave, before Omphale (daughter of Iardanus) set Heracles free and married him, Heracles fathered a son, Cleodaeus, on a slave-woman. This fits, though in Herodotus the son of Heracles and the slave-girl of Iardanus is named Alcaeus.

But according to the historian Xanthus of Lydia (5th century BCE) as cited by Nicolaus of Damascus, the Heraclid dynasty of Lydia traced their descent to a son of Heracles and Omphale named Tylon, and were called Tylonidai. We know from coins that this Tylon was a native Anatolian god equated with the Greek Heracles.

Herodotus asserts that the first of the Heraclids to reign in Sardis was Agron, the son of Ninus, son of Belus, son of Agelaus, son of Heracles. But later writers know a Ninus who is the primordial king of Assyria, and they often call this Ninus son of Belus. Their Ninus is the legendary founder and eponym of the city of Ninus, referring to Ninevah, while Belus, though sometimes treated as a human, is identified with the god Bel.

An earlier genealogy may have made Agron, as a legendary first king of an ancient dynasty, to be a son of the mythical Ninus, son of Belus, and stopped at that point. In the genealogy given by Herodotus, someone may have grafted the tradition of a Lydian son of Heracles at the top end of it, so that Ninus and Belus in the list now become descendants of Heracles, who just happen to bear the same names as the more famous Ninus and Belus.

That, at least, is the interpretation of later chronographers who also ignored Herodotus' statement that Agron was the first to be a king, and included Alcaeus, Belus, and Ninus in their List of Kings of Lydia.

As to how Agron gained the kingdom from the older dynasty descended from Lydus son of Atys, Herodotus only says that the Heraclides, "having been entrusted by these princes with the management of affairs, obtained the kingdom by an oracle."

Strabo (5.2.2) makes Atys father of Lydus, and Tyrrhenus to be one of the descendants of Heracles and Omphale. But all other accounts place Atys, Lydus, and Tyrrhenus brother of Lydus among the pre-Heraclid kings of Lydia.

In art

- One of the most famous symphonic poems in a mythological series composed by the French composer Camille Saint-Saëns in the 1870s is titled Le Rouet d'Omphale, or The Spinning Wheel Of Omphale, the rouet being a spinning wheel that the queen and her maidens used—in this version of the myth, it was Delphic Apollo who condemned the hero to serve the Lydian queen disguised as a woman. In the 20th century, during the "Golden Age Of Radio," this symphonic poem gained wider public exposure when it was used as the theme music for The Shadow.

- Hercules und Omphale is a painting by the 16th century German painter Lucas Cranach the Elder. It features Hercules being dressed up as a woman by Omphale and two maids. Hercules is also spinning wool.

- Omphale is a tragédie lyrique by Jean-Baptiste Philibert Cardonne, premiered at the Palais-Royal in Paris, on 2 May 1769

- Hercule et Omphale is a short, sexually explicit poem by the French poet Guillaume Apollinaire appearing in the erotic (and for many years forbidden) novel Les onze mille verges (The Eleven Thousand Penises).[9]

- In August Strindberg's The Father (1887), the protagonist, Captain Adolf, likens his wife's mistreatment of him to Omphale's behavior toward Heracles. "Omphale!" He screams. "It's Queen Omphale herself! Now you play with Hercules' club while he spins your wool!"

Notes

- ^ Bibliotheke surviving in a first or second-century CE edition, is traditionally ascribed to Apollodorus.

- ^ Aeschylus, Agamemnon 1024-25.

- ^ "No connection between the two has been established, difficult as it is to believe there was no connection between them in early religion." (Elmer G. Suhr, "Herakles and Omphale" American Journal of Archaeology 57.4 (October 1953, pp. 251-263) p. 259f.

- ^ Sophocles, The Trachiniae 69ff.

- ^ According to Diodorus, his sons accepted it.

- ^ (Suhr 1953:251 note).

- ^ Lucian (Dialogues of the Gods) and Tertullian (De pallio 4) both allude to the disgrace.

- ^ Fasti 2.305.

- ^ For the text, see Les onze mille verges

References

- Kerenyi, Karl, 1959. The Heroes of the Greeks, pp 192–97.

Preceded by

MegaraWives of Heracles Succeeded by

DeianiraCategories:- Greek mythology

- Kings of Lydia

- Mythological queens

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.