- Verge escapement

-

The verge (or crown wheel) escapement is the earliest known type of mechanical escapement, the mechanism in a mechanical clock that controls its rate by advancing the gear train at regular intervals or 'ticks'. Its origin is unknown. Verge escapements were used from the 14th century until about 1800 in clocks and pocketwatches. The name verge comes from the Latin virga, meaning stick or rod.[1]

Its invention is important in the history of technology, because it made possible the development of all-mechanical clocks. This caused a shift from measuring time by continuous processes, such as the flow of liquid in water clocks, to repetitive, oscillatory processes, such as the swing of pendulums, which had the potential to be more accurate.[2][3] Oscillating timekeepers are at the heart of every clock today.

Contents

Verge and foliot clocks

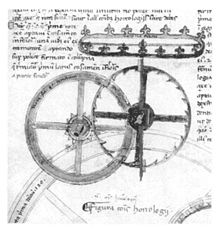

The earliest existing drawing[4] of a verge escapement, in Giovanni De Dondi's astronomical clock, the Astrarium, built 1364, Padua, Italy. This had a balance wheel (crown shape at top) instead of a foliot. The escapement is just below it. From his 1364 clock treatise, Il Tractatus Astrarii.[4]

The earliest existing drawing[4] of a verge escapement, in Giovanni De Dondi's astronomical clock, the Astrarium, built 1364, Padua, Italy. This had a balance wheel (crown shape at top) instead of a foliot. The escapement is just below it. From his 1364 clock treatise, Il Tractatus Astrarii.[4]

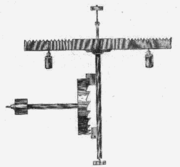

The first evidence of the verge escapement dates from 14th century Europe, where its invention led to the development of the first all-mechanical clocks.[3][5][6] Starting in the 13th century, large tower clocks were built in European town squares and cathedrals. They kept time by using the verge escapement to drive a horizontal bar with weights on the ends called the foliot, a primitive type of balance wheel, to oscillate back and forth. The rate of the clock could be adjusted by sliding the weights in or out on the foliot bar.

The verge probably evolved from the alarum, which used the same mechanism to ring a bell and had appeared centuries earlier.[7][8] However, it may never be known when the escapement was first used in clocks, because it has proven impossible to distinguish from existing documentation which of these early tower clocks were mechanical, and which were water clocks.[9] The same Latin word, horologe, was used for both. There is speculation that Villard de Honnecourt invented the verge escapement in 1237 with an illustration of a questionable device.[10][11] Sources differ on which was the first clock 'known' to be mechanical, depending on which manuscript evidence they regard as conclusive. One candidate is the clock built at the Palace of the Visconti, Milan, Italy, in 1335.[12] However, there is agreement that mechanical clocks existed by the late 13th century.[3][9][13]

Actually, the earliest description of an escapement, in Richard of Wallingford's 1327 manuscript Tractatus Horologii Astronomici on the clock he built at the Abbey of St. Albans, was not a verge, but a variation called a 'strob' escapement.[4][14] It consisted of a pair of escape wheels on the same axle, with alternating radial teeth. The verge rod was suspended between them, with a short crosspiece that rotated first in one direction and then the other as the staggered teeth pushed past. Although no other example is known, it is possible that this design preceded the verge in clocks.[4]

How accurate these early verge and foliot clocks were is debatable, with estimates of one to two hours[15] being mentioned. Early verge clocks were probably no more accurate than the previous water clocks, but they did not freeze in winter and were a more promising technology for innovation. By the mid-17th century, when the pendulum replaced the foliot, the best verge and foliot clocks had achieved an accuracy of 15 minutes per day.

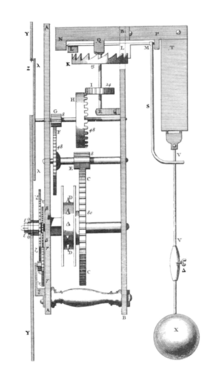

Verge pendulum clocks

Most of the gross inaccuracy of verge and foliot clocks was not due to the escapement itself, but to the foliot oscillator. The invention of the pendulum around 1656 suddenly increased the accuracy of the verge clock from hours a day to minutes a day . Most clocks were rebuilt with their foliots replaced by pendula,[16][17] to the extent that it is difficult to find original verge and foliot clocks intact today. A similar increase in accuracy in verge watches followed the introduction of the balance spring in 1658.

How it works

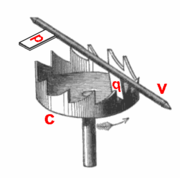

The verge escapement consists of a wheel shaped like a crown, with sawtooth-shaped teeth protruding axially toward the front, and with its axis oriented horizontally. In front of it is a vertical rod, the verge, with two metal plates, the pallets, that engage the teeth at opposite sides of the crown wheel. The pallets are not parallel, but are oriented with an angle in between them so only one catches the teeth at a time. The balance wheel (or the pendulum) is mounted at the end of the verge rod. As the clock's gears turn the crown wheel, one of its teeth pushes on a pallet, rotating the verge in one direction, and rotating the second pallet into the path of the teeth on the opposite side of the wheel, until the tooth pushes past the first pallet. Then a tooth on the wheel's opposite side contacts the second pallet, rotating the verge back the other direction, and the cycle repeats. The result is to change the rotary motion of the wheel to an oscillating motion of the verge. Each swing of the foliot or pendulum thus allows the wheel train of the clock to advance by a fixed amount, moving the hands forward at a constant rate.

The crown wheel must have an odd number of teeth for the escapement to function. The usual angle between the pallets was 90° to 105°, resulting in a foliot or pendulum swing of around 80° to 100°. In order to reduce the pendulum's swing to make it more isochronous, the French used larger pallet angles, upwards of 115°. This reduced the pendulum swing to around 50° and reduced recoil (below), but required the verge to be located so near the crown wheel that the teeth fell on the pallets very near the axis, reducing initial leverage and increasing friction, thus requiring lighter pendulums.[18][19]

Disadvantages

As might be expected from its early invention, the verge is the most inaccurate of the widely-used escapements. It suffers from these problems:

- Verge clocks are sensitive to changes in the drive force; they slow down as the mainspring unwinds. This is called lack of isochronism. It was much worse in verge and foliot clocks due to the lack of a balance spring, but is a problem in all verge movements. In fact, the standard method of adjusting the rate of early verge watches was to alter the force of the mainspring.[20] The cause of this problem is that the crown wheel teeth are always pushing on the pallets, driving the pendulum (or balance wheel) throughout its cycle; it is never allowed to swing freely. All verge watches and spring driven clocks required fusees to equalize the force of the mainspring to achieve even minimal accuracy.

- The escapement has "recoil", meaning that the momentum of the foliot or pendulum pushes the crown wheel backward momentarily, causing the clock's wheel train to move backward, during part of its cycle. This increases friction and wear, resulting in inaccuracy. One way to tell whether an antique watch has a verge escapement is to observe the second hand closely; if it moves backward a little during each cycle, the watch is a verge. This is not necessarily the case in clocks, as there are some other pendulum escapements which exhibit recoil.

- In pendulum clocks, the wide pendulum swing angles of 80°-100° required by the verge cause an additional lack of isochronism due to circular error.

- The wide pendulum swings also cause a lot of air friction, reducing the accuracy of the pendulum, and requiring a lot of power to keep it going, increasing wear.[21] So verge pendulum clocks had lighter bobs, which reduced accuracy.

- Verge timepieces tend to accelerate as the crown wheel and the pallets wear down. This is particularly evident in verge watches from the mid-18th century onwards. It is not in the least unusual for these watches, when run today, to gain many hours per day, or to simply spin as if there were no balance present. The reason for this is that as new escapements were invented, it became the fashion to have a thin watch. To achieve this in a verge watch requires the crown wheel to be made very small, magnifying the effects of wear.

Decline

Verge escapements were used in virtually all clocks and watches for 400 years. Then the increase in accuracy due to the introduction of the pendulum and balance spring in the mid 17th century focused attention on error caused by the escapement. By the 1820s, the verge was superseded by better escapements, though many examples of mid 19th century verge watches exist, as they were much cheaper by this time. These later verge watches were colloquially called 'turnips' because of their bulky build.

In pocketwatches, besides its inaccuracy, the vertical orientation of the crown wheel and the need for a bulky fusee made the verge movement unfashionably thick. French watchmakers adopted the thinner cylinder escapement, invented in 1695. In England, high end watches went to the duplex escapement, developed in 1782, but inexpensive verge fusee watches continued to be produced until the mid 19th century, when the lever escapement took over.[22][23]

The verge was only used briefly in pendulum clocks before it was replaced by the anchor escapement, invented around 1660 and widely used beginning in 1680. The problem with the verge was that it required the pendulum to swing in a wide arc of 80° to 100°. Christiaan Huygens in 1674 showed that a pendulum swinging in a wide arc is an inaccurate timekeeper, because its period of swing is sensitive to small changes in the drive force provided by the clock mechanism.

Although the verge is not known for accuracy, it is capable of it. The first successful marine chronometers, H4 and H5, made by John Harrison in 1759 and 1770, used verge escapements with diamond pallets.[24][25][26] In trials they were accurate to within a fifth of a second per day.[27]

Today the verge is seen only in antique or antique-replica timepieces. Many original bracket clocks have their Victorian-era anchor escapement conversions undone and the original style of verge escapement restored. Clockmakers call this a verge reconversion.

Notes

- ^ Harper, Douglas (2001). "Verge". Online Etymology Dictionary. http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?term=verge. Retrieved 2008-06-22.

- ^ Marrison, Warren (1948). "The Evolution of the Quartz Crystal Clock". Bell System Technical Journal 27: 510–588. http://www.ieee-uffc.org/freqcontrol/marrison/Marrison.html. Retrieved 2007-06-06.

- ^ a b c Cipolla, Carlo M. (2004). Clocks and Culture, 1300 to 1700. W.W. Norton & Co.. ISBN 0393324435. http://books.google.com/?id=YSf9MVxa2JEC&pg=PA31&dq=verge+escapement+technology., p.31

- ^ a b c d North, John David (2005). God's Clockmaker: Richard of Wallingford and the Invention of Time. London, UK: Hambledon & London. pp. 179, fig.33. ISBN 1852854510. http://books.google.com/?id=rAuj1_x34XoC&pg=PA179&dq=%22quadratura+plumborum%22+%22Richard+of+Wallingford%22.

- ^ "Escapement". Encyclopædia Britannica online. 2007. http://www.britannica.com/eb/article-9032979/escapement#5666.hook. Retrieved 2007-10-26.

- ^ White, Lynn, Jr. (1962). Medieval Technology and Social Change. UK: Oxford Univ. Press. pp. 119.

- ^ Headrick, Michael (2002). "Origin and Evolution of the Anchor Clock Escapement". Control Systems magazine, (Inst. of Electrical and Electronic Engineers) 22 (2). Archived from the original on 2009-10-25. http://web.archive.org/web/20091025120920/http://geocities.com/mvhw/anchor.html. Retrieved 2007-06-06.

- ^ Dohrn-van Rossum, Gerhard (1996). History of the Hour: Clocks and Modern Temporal Orders. Univ. of Chicago Press. ISBN 0226155110. http://books.google.com/?id=xYhlNoUu-toC&dq=verge+escapement+technology., p.103-104

- ^ a b White 1966, p.124

- ^ "Machines: Saw, Trap, Hoist, and Automata". Bib. Nat. ms. fr. 19093, fol. 44, Villard de Honnecourt. AVISTA website. http://orgs.uww.edu/avista/engines.htm. Retrieved 2007-11-08.

- ^ "The First Mechanical Clocks". John H. Lienhard. The Engines of Our Ingenuity. NPR. KUHF-FM Houston. 2000. No. 1506. Transcript.

- ^ Usher, Abbot Payson (1988). A History of Mechanical Inventions. Courier Dover. ISBN 048625593X. http://books.google.com/?id=xuDDqqa8FlwC&pg=PA196., p.196

- ^ Whitrow 1989, p.104

- ^ Dohrn-van Rossum, Gerhard (1996). History of the Hour: Clocks and Modern Temporal Orders. Univ. of Chicago Press. pp. 50–52. ISBN 0226155110. http://books.google.com/?id=xYhlNoUu-toC&dq=verge+escapement+technology.

- ^ Milham, Willis I. (1945). Time and Timekeepers. New York: MacMillan. p. 83. ISBN 0780800087.

- ^ "Big Clocks". Science Museum, UK. 2007. http://www.sciencemuseum.org.uk/onlinestuff/stories/the_wells_cathedral_clock.aspx?page=2. Retrieved 2007-06-06.

- ^ Milham 1945, p.144

- ^ Britten, Frederick J. (1896). The Watch and Clock Maker's Handbook, 9th Ed.. London: E.F. & N. Spon. http://books.google.com/?id=5SYJAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA392., p.391-392

- ^ Glasgow, David (1885). Watch and Clock Making. London: Cassel & Co.. http://books.google.com/?id=9wUFAAAAQAAJ&pg=PA124., p.124-126

- ^ Perez, Carlos (2001). "Artifacts of the Golden Age, part 1". Carlos's Journal. TimeZone. http://www.timezone.com/library/cjrml/cjrml0006. Retrieved 2007-06-06.

- ^ Headrick 2002

- ^ Perez 2001, pp.8

- ^ Second Time Around 2007

- ^ Perez 2001, pp.11

- ^ Headrick 2002, pp.2

- ^ Hird, Jonathan R., Betts, Jonathan D. & Pratt, D. The Diamond Pallets of John Harrison's Longitude Timekeeper–H4. Annals of Science, volume 65, Issue 2, April 2008, pg 171-200

- ^ "A Walk Through Time, part 3: A Revolution in Timekeeping". NIST. 2002. Archived from the original on 2007-05-28. http://web.archive.org/web/20070528005441/http://physics.nist.gov/GenInt/Time/revol.html. Retrieved 2007-06-06.

See also

- Galileo's escapement - a proposed replacement of the Verge Escapement by Galileo Galilei

- Salisbury cathedral clock—oldest known operating clock, with verge and foliot escapement

External links

- Weight Driven Clock Encyclopædia Britannica article has animation showing operation of a verge and foliot.

- Drawing of verge and foliot on commercial website

- Elytra Design, Diagram of verge and foliot escapement on commercial website

- Mark Frank (2005), The Evolution of Tower Clock Movements Paper with much technical information on early verge clocks by tower clock restorer, with many unique pictures of movements, references.

- WoodenClockWorks—Verge and foliot clock kits.

- History of Mechanical Clocks with Animations

Categories:- Escapements

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.