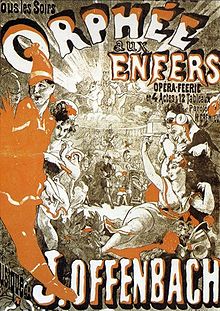

- Orpheus in the Underworld

-

Jacques Offenbach  Operas

Operas- Les deux aveugles (1855)

- Le violoneux (1855)

- Ba-ta-clan (1855)

- La rose de Saint-Flour (1856)

- Le 66 (1856)

- Le financier et le savetier (1856)

- La bonne d'enfant (1856)

- Croquefer, ou Le dernier des paladins (1857)

- Le mariage aux lanternes (1857)

- Mesdames de la Halle (1858)

- La chatte métamorphosée en femme (1858)

- Orpheus in the Underworld (1858)

- Geneviève de Brabant (1859)

- Daphnis et Chloé (1860)

- Le pont des soupirs (1861)

- M. Choufleuri restera chez lui le . . . (1861)

- Monsieur et Madame Denis (1862)

- Les bavards (1862)

- Il signor Fagotto (1863)

- Lischen et Fritzchen (1863)

- Die Rheinnixen (1864)

- La belle Hélène (1864)

- Barbe-bleue (1866)

- La vie parisienne (1866)

- La Grande-Duchesse de Gérolstein (1867)

- Robinson Crusoé (1867)

- L'île de Tulipatan (1868)

- La Périchole (1868)

- Les brigands (1869)

- Le roi Carotte (1872)

- Fantasio (1872)

- Pomme d'api (1873)

- Maître Péronilla (1873)

- La jolie parfumeuse (1873)

- Bagatelle (1874)

- Madame l'archiduc (1874)

- Le voyage dans la lune (1875)

- Madame Favart (1878)

- La fille du tambour-major (1879)

- The Tales of Hoffmann (1880, unfinished)

Orphée aux enfers (Orpheus in the Underworld) is an opéra bouffon (a form of operetta), or opéra féerie in its revised version, by Jacques Offenbach. The French text was written by Ludovic Halévy and later revised by Hector-Jonathan Crémieux.

The work, first performed in 1858, is said to be the first classical full-length operetta.[1][2] Offenbach's earlier operettas were small-scale one-act works, since the law in France did not allow certain genres of full-length works. Orpheus was not only longer, but more musically adventurous than Offenbach's earlier pieces.[3]

This also marked the first time that Offenbach used Greek mythology as a backdrop for one of his buffooneries. The operetta is an irreverent parody and scathing satire on Gluck and his Orfeo ed Euridice and culminates in the risqué galop infernal ("Infernal Galop") that shocked some in the audience at the premiere. Other targets of satire, as would become typical in Offenbach's burlesques, are the stilted performances of classical drama at the Comédie Française and the scandals in society and politics of the Second French Empire.

The Infernal Galop from Act II, Scene 2, is famous outside classical circles as the music for the "Can-can" (to the extent that the tune is widely, but erroneously, called "Can-can") . Saint-Saëns borrowed the Galop, slowed it to a crawl, and arranged it for the strings to represent the tortoise in The Carnival of the Animals.

Contents

Performance history

The first performance of the two-act, opéra bouffe version took place at the Théâtre des Bouffes Parisiens in Paris on 21 October 1858 and ran for an initial 228 performances. It then returned to the stage a few weeks later, after the cast had had a rest. For the Vienna production of 1860, Carl Binder provided an overture that became famous, beginning with its bristling fanfare, followed by a tender love song, a dramatic passage, a complex waltz, and, finally, the renowned Can-can music.[citation needed]

The piece then played in German at the Stadt Theatre, on Broadway, beginning in March, 1861. Next, it had a run of 76 performances at Her Majesty's Theatre, in London, beginning on 26 December 1865, in an adaptation by J. R. Planché.[citation needed]

A four-act version, designated as an opéra féerie, was first performed at the Théâtre de la Gaîté on 7 February 1874.[4] (This has proved less popular over time than the original two act version.)

Sadler's Wells opera presented an English version by Geoffrey Dunn beginning on 16 May 1960.[citation needed] In the 1980s, English National Opera staged the opera freely translated into English by Snoo Wilson with David Pountney. The production was notable for its satirical portrayal of the then Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher as the character Public Opinion. The first performance was at the Coliseum Theatre in London on 5 September 1985.[5] The revived D'Oyly Carte Opera Company performed the work in the 1990s.[6]

Critical appreciation

In the eyes of Clément and Larousse[7] the piece is une parodie grotesque et grossière (a coarse and grotesque parody), full of vulgar and indecent scenes that give off une odeur malsaine (an unhealthy odor). In the opinion of Piat, however, Offenbach's Orphée is, like most of his major operettas, a bijou (jewel) that only snobs will fail to appreciate.[8] The piece was not immediately a hit, but critics' condemnation of it, particularly that of Jules Janin, who called it a "profanation of holy and glorious antiquity," only provided vital publicity, serving to heighten the public's curiosity to see the piece.[9]

Roles

Role Voice type Premiere cast

(two act version), 21 October 1858

(Conductor: Jacques Offenbach )Premiere cast

(four act version), 7 February 1874

(Conductor: Jacques Offenbach )Cupidon (Cupid), god of love soprano Coralie Guffroy Matz-Ferrare Diane (Diana), goddess of chastity soprano Chabert Berthe Perret Eurydice, wife of Orphée soprano Lise Tautin Marie Cico John Styx, servant of Pluton, formerly king of Boeotia baritone or tenor Debruille-Bache Alexandre Junon (Juno), wife of Jupiter mezzo-soprano Marguerite Chabert Lyon Jupiter, king of the gods baritone Désiré Christian Public Opinion mezzo-soprano Marguerite Macé-Montrouge Elvire Gilbert Mars, god of war bass Floquet Mercure (Mercury), messenger of the gods tenor Jean-François Philbert Pierre Grivot Minerve (Minerva), goddess of wisdom soprano Marie Cico Morphée (Morpheus), god of sleep tenor Marchand Orphée (Orpheus), a musician tenor Tayau Meyronnet Pluton (Pluto), god of the underworld, disguised as Aristée (Aristaeus), a farmer tenor Léonce Montaubry Vénus (Venus), goddess of beauty contralto Marie Garnier Angèle Amour mezzo-soprano Gervais/Enjalbert Matz-Ferrare Bacchus, god of wine spoken Antognini Cerbère (Cerberus), three-headed guardian of the underworld barked Tautin snr. Minos baritone/tenor Georges Dejon-Marchand Éaque (Aeacus) tenor -- Rhadamante (Rhadamanthus) bass -- Gods, goddesses, shepherds, shepherdesses, lictors and spirits in the underworld Synopsis (original two-act opéra bouffe version)

Act 1

Scene 1: Near Thebes

A melodrama (Introduction and Melodrame) opens the work. Public Opinion explains who she is - the guardian of morality ("Qui suis-je? du Théâtre Antique"). She seeks to rework the story of Orphée (Orpheus) and Eurydice - who, despite being husband and wife, hate each other - into a moral tale for the ages. However, she has her work cut out for her: Eurydice is in love with the shepherd, Aristée (Aristaeus), who lives next door ("La femme dont le coeur rêve"), and Orphée is in love with Chloë, a shepherdess. When Orphée mistakes Eurydice for her, everything comes out, and Eurydice insists they break the marriage off. However Orphée, fearing Public Opinion's reaction, torments her into keeping the scandal quiet using violin music, which she hates.

We now meet Aristée - who is, in fact, Pluton (Pluto) - keeping up his disguise by singing a pastoral song about those awful sheep ("Moi, je suis Aristée"). Since Pluton was originally played by a famous female impersonator, this song contains numerous falsetto notes. Eurydice, however, has discovered what she thinks is a plot by Orphée to kill Aristée, but is in fact a conspiracy between him and Pluton to kill her, so Pluton may have her. Pluton tricks her into walking into the trap by showing immunity to it, and, as she dies, transforms into his true form (Transformation Scene) Eurydice finds that death is not so bad when the God of Death is in love with you ("La mort m'apparaît souriante"), and so keeps coming back for one more verse. They descend into the Underworld as soon as Eurydice has left a note telling her husband she has been unavoidably detained (Descent to the Underworld).

All seems to be going well for Orphée until Public Opinion catches up with him, and threatens to ruin his violin teaching career unless he goes to rescue his wife. Orphée reluctantly agrees.

Scene 2: Olympus

The scene changes to Olympus, where the Gods sleep out of boredom ("Dormons, dormons"). Things look a bit more interesting for them when Diane (Diana) returns and begins gossiping about Actaeon, her current love ("Quand Diane descend dans la plaine"). However, Jupiter, shocked at the behaviour of the supposedly virgin goddess, has turned Actaeon into a stag. Pluton then arrives, and reveals to the other gods the pleasures of Hell, leading them to revolt against horrid ambrosia, hideous nectar, and the sheer boredom of Olympus ("Aux armes, dieux et demi-dieux!"). Jupiter's demands to know what is going on lead them to point out his hypocrisy at great length, describing - and poking fun of - all his mythological affairs. However, little further progress can be made before news of Orphée's arrival forces the gods to get onto their best behaviour. Pluton is worried he will be forced to give Eurydice back, and, after a quotation from Gluck's Orfeo ed Euridice sends the gods to tears, Jupiter announces that he is going to Hell to sort everything out. The other gods beg to come with him, he consents, and mass celebration breaks out at this holiday ("Gloire! gloire à Jupiter").

Act 2

Scene 1

Eurydice is being kept locked up by Pluto, and is finding life very dull. Her gaoler, a dull-witted tippler by the name of John Styx, is not helping, particularly his habit of telling, at the slightest provocation, all about how he was King of the Boeotians until he died. But if he had not died, he would still be king ("Quand j'étais roi de Béotie").1

1 Boeotia is a part of Greece that Aristophanes fills with idiotic rural rubes - rather appropriate for this Styx.

Jupiter spots where Pluton hid Eurydice whilst being shown around by him, and slips through the keyhole by turning into a beautiful, golden fly. He meets Eurydice on the other side, and sings a love duet with her where his part consists entirely of buzzing ("Bel insecte à l'aile dorée"). Afterwards, he reveals himself to her, and promises to help her, largely because he wants her for himself.

Scene 2

The scene shifts to a huge party the gods are having in Hell, where ambrosia, nectar, and propriety are nowhere to be seen ("Vive le vin! Vive Pluton!"). Eurydice sneaks in disguised as a bacchante ("J'ai vu le dieu Bacchus"), but Jupiter's plan to sneak her out is interrupted by calls for a dance. Unfortunately, Jupiter can only dance minuets which everyone else finds boring and awful ("La la la. Le menuet n'est vraiment si charmant"). Things liven up, though, as the most famous number in the operetta, the Galop Infernal (best known as the music of the Can-can) starts, and everyone throws himself into it with wild abandon ("Ce bal est original").

Ominous violin music heralds the approach of Orphée (Entrance of Orphée and Public Opinion), but Jupiter has a plan, and promises to keep Eurydice away from him. As with the standard myth, Orphée must not look back, or he will lose Eurydice forever ("Ne regarde pas en arrière!"). Public Opinion keeps a close eye on him, to keep him from cheating, but Jupiter throws a lightning bolt, making him jump and look back, and so all ends happily, with a reprise of the Galop.

Libretto

- Orphée aux enfers (French Wikisource)

Recordings

Audio

The operetta has been recorded many times.

- 1951: An historic recording by René Leibowitz and the Paris Philharmonic available on compact disc (REGIS RRC 2063). Michel Plasson recorded the work with Mady Mesplé in 1978 (EMI CDS7496472).

- 1987: The English National Opera production, released on CD by That's Entertainment Records (CDTER 1134)

- 1999: Marc Minkowski conducted the operetta (two-act version with some extras from the 4-act one) in Lyon, with a cast including Natalie Dessay, Laurent Naouri, Jean-Paul Fouchécourt, Véronique Gens, Patricia Petibon, and Ewa Podles (EMI 0724355672520).

There is a recording in English (highlights only) by The Sadlers Wells Opera with June Bronhill as Euridice and Eric Shilling as Jupiter.

Video

- 1997: Minkowski is also the conductor on a DVD, again at Lyon with Natalie Dessay, Laurent Naouri, and Jean-Paul Fouchécourt, as well as Yann Beuron and others in a production by Laurent Pelly (TDK DV-OPOAE). Again this is basically the two-act version. (An excerpt from the Jupiter/Eurydice seduction duet is on YouTube [1], in which, as he performs oral stimulation on her, she climaxes at the high note.)

References

- Notes

- ^ The New Penguin Opera Guide, ed. Amanda Holden, Penguin Books, London 2001

- ^ The Penguin Concise Guide to Opera, ed. Amanda Holden, Penguin Books, London 2005

- ^ Orphée aux enfers by Andrew Lamb, in 'The New Grove Dictionary of Opera', ed. Stanley Sadie (London, 1992) ISBN 0-333-73432-7

- ^ From Musical Theatre Guide

- ^ Sleeve notes to the CD recording of the ENO production: CDTER 1134

- ^ Milnes, Rodney. "All down to a hell of a good snigger – Opera". The Times, 22 Monday, March 1993; and Sutcliffe, Tom. "Styx for Kicks", The Guardian 21 April 1993, p. A6

- ^ Félix Clément and Pierre Larousse: Dictionnaire des opéras (rev. Arthur Pougin), Da Capo Press Music Reprint Series, New York 1969

- ^ Jean-Bernard Piat: Guide du mélomane averti, Le Livre de Poche 8026, Paris 1992

- ^ From Answers.com

- Sources

- Amadeus Almanac (1858), accessed 20 November 2008

- Amadeus Almanac (1874), accessed 20 November 2008

- Orphée aux enfers by Andrew Lamb, in 'The New Grove Dictionary of Opera', ed. Stanley Sadie (London, 1992) ISBN 0-333-73432-7

- The Opera Goer's Complete Guide by Leo Melitz, 1921 version.

- Information about the operetta from Musical Theatre Guide

- Information from the NODA website

- Information from Answers.com

Categories:- Operas by Jacques Offenbach

- French-language operas

- 1858 operas

- Operas

- Opéras bouffons

- Opéras féeries

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.