- The Tales of Hoffmann

-

This article is about Offenbach's opera. For Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger's 1951 film of the opera, see The Tales of Hoffmann (film).

Jacques Offenbach  Operas

Operas- Les deux aveugles (1855)

- Le violoneux (1855)

- Ba-ta-clan (1855)

- La rose de Saint-Flour (1856)

- Le 66 (1856)

- Le financier et le savetier (1856)

- La bonne d'enfant (1856)

- Croquefer, ou Le dernier des paladins (1857)

- Le mariage aux lanternes (1857)

- Mesdames de la Halle (1858)

- La chatte métamorphosée en femme (1858)

- Orpheus in the Underworld (1858)

- Geneviève de Brabant (1859)

- Daphnis et Chloé (1860)

- Le pont des soupirs (1861)

- M. Choufleuri restera chez lui le . . . (1861)

- Monsieur et Madame Denis (1862)

- Les bavards (1862)

- Il signor Fagotto (1863)

- Lischen et Fritzchen (1863)

- Die Rheinnixen (1864)

- La belle Hélène (1864)

- Barbe-bleue (1866)

- La vie parisienne (1866)

- La Grande-Duchesse de Gérolstein (1867)

- Robinson Crusoé (1867)

- L'île de Tulipatan (1868)

- La Périchole (1868)

- Les brigands (1869)

- Le roi Carotte (1872)

- Fantasio (1872)

- Pomme d'api (1873)

- Maître Péronilla (1873)

- La jolie parfumeuse (1873)

- Bagatelle (1874)

- Madame l'archiduc (1874)

- Le voyage dans la lune (1875)

- Madame Favart (1878)

- La fille du tambour-major (1879)

- The Tales of Hoffmann (1880, unfinished)

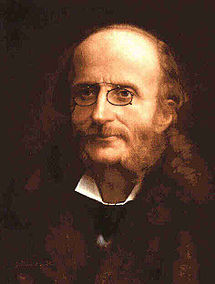

Les contes d'Hoffmann (The Tales of Hoffmann) is an opéra by Jacques Offenbach. The French libretto was written by Jules Barbier, based on short stories by E. T. A. Hoffmann, who is the main protagonist in the opera (as he is in the stories).

Barbier, together with Michel Carré, had written a play, Les contes fantastiques d'Hoffmann, produced at the Odéon Theatre in Paris in 1851, which Offenbach had seen.[1]

The stories upon which the opera is based are "Die Gesellschaft im Keller", "Der Sandmann" ("The Sandman", 1816),[2] "Rath Krespel" ("Councillor Krespel", also known in English as "The Cremona Violin", 1818),[3] and "Das verlorene Spiegelbild" ("The Lost Reflection") from Die Abendteuer der Sylvester-Nacht (The Adventures of New Year's Eve, 1814). The "Chanson de Kleinzach" aria in the Prologue is based on the short story "Klein Zaches, genannt Zinnober" (1819).

Contents

Performance history

The opera was first performed in a public venue, without the 'Giulietta' act, at the Opéra-Comique on 10 February 1881.[4] It had been presented in an abridged form at the house of Offenbach, 8 Boulevard des Capucines, on 18 May 1879, with Madame Franck-Duvernoy in the soprano roles, Auguez as Hoffmann (baritone) and Émile-Alexandre Taskin in the four villain roles, with Edmond Duvernoy at the piano and a chorus directed by Albert Vizentini. As well as Carvalho of the Opéra-Comique, the director of the Ringtheater in Vienna, Franz von Jauner was also present, and a four-act version with recitatives was staged there on 7 December 1881, although a gas explosion and fire occurred at the theatre after the second performance.[5]

The opera reached its hundredth performance at the Salle Favart on the 15 December 1881,[4] but the fire at the Opéra-Comique in 1887 destroyed the orchestral parts,[5] and it was not seen again in Paris until 1893 at the Salle de la Renaissance du Théâtre-Lyrique when it received 20 performances.[6] A new production by Albert Carré (including the Venice act) was mounted at the Opéra-Comique in 1911, with Léon Beyle in the title role and Albert Wolff conducting; this remained in the repertoire until the Second World War, reaching 700 performances of the piece at the theatre.[4] Following a recording by Opéra-Comique forces in March 1948 Louis Musy created the first post-war production in Paris, conducted by André Cluytens.[4] The Paris Opera first staged the work in October 1974, directed by Patrice Chéreau with Nicolai Gedda in the title role.[7]

Outside France, the piece was mounted in Geneva, Budapest, Hamburg, New York and Mexico in 1882, Vienna (Theater an der Wien), Prague and Anvers in 1883 and Lvov and Berlin in 1884. Later local premieres included Buenos Aires in 1894, St Petersburg in 1899, Barcelona in 1905 and London in 1910.[7]

Roles

Role Voice type Premiere cast,

10 February 1881

(Conductor: Jules Danbé)Complete with 'Giulietta Act',

7 December 1881

(Conductor: Joseph Hellmesberger, Jr.[8])Hoffmann, a poet tenor Jean-Alexandre Talazac Olympia, a mechanical doll soprano Adèle Isaac Antonia, a young girl soprano Adèle Isaac Giulietta, a courtesan soprano Stella, a singer soprano Adèle Isaac Lindorf, Coppélius, Miracle bass-baritone Émile-Alexandre Taskin Dapertutto bass-baritone Andrès, Cochenille, Frantz tenor Pierre Grivot Pitichinaccio tenor Crespel, Antonia's father bass Hippolyte Belhomme Hermann, a student bass Teste Wolfram, a student bass Piccaluga Wilhelm, a student bass Collin Luther bass Troy Nathanaël, a student tenor Chennevières Nicklausse mezzo-soprano Marguerite Ugalde The muse mezzo-soprano Mole-Truffier Peter Schlémil, in love with Giulietta bass Spalanzani, an inventor tenor E. Gourdon Voice of the mother of Antonia soprano Dupuis Students, Guests Synopsis

Prologue

A tavern in Nuremberg. The Muse appears and reveals to the audience that her purpose is to draw Hoffmann's attention to herself, and to make him abjure all other loves, so he can be devoted fully to her: poetry. She takes the appearance of Hoffmann's closest friend, Nicklausse. The prima donna Stella, currently performing Mozart's Don Giovanni sends a letter to Hoffmann, requesting a meeting in her dressing room after the performance. The letter, and the key to the room, are intercepted by Councillor Lindorf (Dans les rôles d'amoureux langoureux), who is the first of the opera's incarnations of evil, Hoffmann's nemesis. Lindorf intends to replace Hoffmann at the rendezvous. In the tavern students are waiting for Hoffmann. He finally arrives and entertains them with the legend of Kleinzach the dwarf (Il ètait une fois à la cour d'Eisenach), and is coaxed by Lindorf into telling the audience about his life's three great loves.

Act 1 (Olympia)

Hoffmann's first love is Olympia, an automaton created by the scientist Spalanzani. Hoffmann falls in love with her, not knowing that Olympia is a mechanical doll (Allons! Courage et confiance...Ah! vivre deux!). Nicklausse, who knows the truth about Olympia, sings a story of a mechanical doll that looked like a human to warn Hoffmann but is ignored by him (Une poupée aux yeux d'émail). Coppélius, Olympia's co-creator and this act's incarnation of Nemesis, sells Hoffmann magic glasses which make Olympia appear as a real woman (J'ai des yeux).

Olympia sings one of the opera's most famous arias Les oiseaux dans la charmille ("The Doll Song") in which she periodically runs down and needs to be wound up before she can continue. Hoffmann is tricked into believing that his affections are returned, to the bemusement of Nicklausse, who subtly tries to warn his friend (Voyez-la sous son éventail). While dancing with Olympia, Hoffmann falls on the ground and his glasses break. At the same time, Coppélius appears and tears Olympia apart, in retaliation for having been tricked out of his fees by Spalanzani. With the crowd laughing at him, Hoffmann realizes that he was in love with an automaton.

Act 2 (Antonia)

After a long search, Hoffmann finds the house where Crespel and his daughter Antonia are hiding. Hoffmann and Antonia loved each other, but were separated when Crespel decided to hide his daughter from Hoffmann. Antonia has inherited her mother's talent for singing, but her father forbids her to sing because of the mysterious illness from which she is suffering. Antonia wishes that her lover would return to her (Elle a fui, la tourterelle). Her father also forbids her to see Hoffmann, who is encouraging Antonia in her musical career, and is therefore a danger to her without knowing it. Crespel tells Frantz, his servant, to stay with his daughter and when he leaves, Frantz sings "Jour et nuit je me mets en quatre".

When Crespel leaves his house, Hoffmann takes advantage of the occasion to sneak in, and the lovers are reunited (love duet:C'est une chanson d'amour). When Crespel comes back, he receives the visit of Dr Miracle, the act's Nemesis, who forces Crespel to let him heal Antonia. Still in the house, Hoffmann listens to the conversation and learns that Antonia may die if she sings too much. He returns to her room to make her promise to give up her artistic dreams. Antonia reluctantly accepts her lover's will. Once she is alone, Dr Miracle enters Antonia's room and tries to persuade her to sing and follow her mother's path to glory, stating that Hoffmann is sacrificing her to his brutishness and loves her only for her beauty. With mystic powers, he raises a vision of Antonia's dead mother and induces Antonia to sing, causing her death. Crespel arrives just in time to witness his daughter's last breath. Hoffmann enters the room and Crespel wants to kill him, thinking that he is responsible for his daughter's death. Nicklausse saves his friend from the old man's vengeance.

Act 3 (Giulietta)

Venice. The act opens with the barcarolle Belle nuit, ô nuit d'amour. Hoffmann falls in love with the courtesan Giulietta and thinks his affections are returned (Amis, l'amour tendre et rêveur). Giulietta is not in love with Hoffmann but only seducing him under the orders of Captain Dapertutto, who has promised to give her a diamond if she filches Hoffmann's reflection from a mirror (Scintille, diamant). The jealous Schlemil (cf. Peter Schlemiel for a literary antecedent), a previous victim of Giulietta and Dapertutto (he gave Giulietta his shadow), challenges the poet to a duel, but is killed. Nicklausse wants to take Hoffmann away from Venice and goes looking for horses. Meanwhile, Hoffmann meets Giulietta and cannot resist her (O Dieu! de quelle ivresse): he gives her his reflection, only to be abandoned by the courtesan, to Dapertutto's great pleasure. Hoffmann tells Dapertutto that his friend Nicklausse will come and save him. Dapertutto prepares a poison to get rid of Nicklausse, but Giulietta drinks it by mistake and drops dead in the arms of the poet.

Epilogue

The tavern in Nuremberg. Hoffmann, drunk, swears he will never love again, and explains that Olympia, Antonia, and Giulietta are three facets of a same person, Stella. They represent, respectively, the young girl's, the musician's, and the courtesan's side of the prima donna. When Hoffmann says he doesn't want to love any more, Nicklausse reveals himself as the Muse and reclaims Hoffmann: "Be reborn a poet! I love you, Hoffmann! Be mine!" The magic of poetry reaches Hoffmann as he sings O Dieu! de quelle ivresse once more, ending with "Muse whom I love, I am yours!" At this moment, Stella, who is tired of waiting for Hoffmann to come to her rendezvous, enters the tavern and finds him drunk. The poet tells her to leave ("Farewell, I will not follow you, phantom, spectre of the past"), and Lindorf, who was waiting in the shadows, comes forth. Nicklausse explains to Stella that Hoffmann does not love her any more, but that Councillor Lindorf is waiting for her. Some students enter the room for more drinking, while Stella and Lindorf leave together.

Editions

Offenbach did not live to see his opera performed. He died on October 5, 1880, four months before its premiere, but after completing the piano score and orchestrating the prologue and first act. As a result, different editions of the opera soon emerged, some bearing little resemblance to the authentic work. The version performed at the opera's premiere was by Ernest Guiraud, who completed Offenbach's scoring and wrote recitatives. Over the years new editions have continued to appear, though the emphasis, particularly since the 1970s, has shifted to authenticity. In this regard a milestone was the Michael Kaye edition of 1992, but then additional authentic music was found and published in 1999. Now finally, in 2011, it seems that two large competing publishing houses – one French, one German – are about to release a joint edition reflecting and reconciling the research of recent decades. When it appears, as part of a grand "Edition Offenbach," we may be as close to a definitive "Contes d'Hoffmann" as we will ever get. Here are the edition "variables" that have plagued the opera since Offenbach died:

- Addition of extra music not written by Offenbach

- Commonly directors choose among two arias in the Giulietta act:

- "Scintille, diamant", based on a tune from the overture to Offenbach's operetta A Journey to the Moon and included by André Bloch for a Monaco production in 1908.

- The Sextet (sometimes called Septet, counting the chorus as a character) of unknown origin, but containing elements of the Barcarolle.

- Changes to the sequence of the acts

- The three acts, telling different stories from the life of Hoffmann, are independent (with the exception of a mention of Olympia in the Antonia act) and can easily be swapped without affecting the overall story. Offenbach's order was Prologue–Olympia–Antonia–Giulietta–Epilogue, but during the 20th century, the work was usually performed with Giulietta's act preceding Antonia's. Only recently has the original order been restored, and even now the practice is not universal. The general reason for the switch is that the Antonia act is more accomplished musically.

- Naming of the acts

- The designation of the acts is disputed. The German scholar Josef Heinzelmann, among others, favours numbering the Prologue as Act One, and the Epilogue as Act Five, with Olympia as Act Two, Antonia as Act Three, and Giulietta as Act Four.

- Changes to the story itself

- The opera was sometimes performed (for example during the premiere at the Opéra-Comique) without the entire Giulietta act, though the famous Barcarolle from that act was inserted into the Antonia act, and Hoffmann's aria "Amis! l'Amour tendre et rêveur" was inserted into the epilogue. In 1881, when the opera was first performed in Vienna, the Giulietta act was restored, but modified so that the courtesan does not die at the end by accidental poisoning, but exits in a gondola accompanied by her servant Pitichinaccio. This ending has been the preferred one since then almost without exception.

- Spoken dialogue vs. recitative

- Due to its opéra-comique genre, the original score contained much dialogue that has sometimes been replaced by recitative, and this lengthened the opera so much that some acts were removed (see above).

- The number of singers performing

- Offenbach intended that the four soprano roles be played by the same singer, for Olympia, Giulietta and Antonia are three facets of Stella, Hoffmann's unreachable love. Similarly, the four villains (Lindorf, Coppélius, Miracle, and Dapertutto) would be performed by the same bass-baritone, because they are all manifestations of evil. While the doubling of the four villains is quite common, most performances of the work use different singers for the loves of Hoffmann. This is because different skills are needed for each role: Olympia requires a skilled coloratura singer with stratospheric high notes, Antonia is written for a more lyric voice, and Giulietta is usually performed by a dramatic soprano or a mezzo-soprano. When all three roles (four if the role of Stella is counted) are performed by a single soprano in a performance, it is considered one of the largest challenges in the lyric-coloratura repertoire. Sopranos who have sung all three roles include Karan Armstrong, Vina Bovy, Edita Gruberová, Fanny Heldy, Catherine Malfitano, Anja Silja, Beverly Sills, Ruth Ann Swenson, Carol Vaness, Ninon Vallin and Virginia Zeani. All four roles have been performed by Josephine Barstow, Diana Damrau, Elizabeth Futral, Elena Moșuc[9] and Joan Sutherland.

A recent version including the authentic music by Offenbach has been reinstated by the French Offenbach scholar Jean-Christophe Keck. A successful performance of this version was produced at the Lausanne Opera (Switzerland). However, most producers still prefer the traditional version published by Éditions Choudens, with additions from a version prepared by Fritz Oeser, for financial reasons. Another recent edition by Michael Kaye has been performed at the Opéra National de Lyon and the Hamburg State Opera with Elena Moşuc singing the roles of Olympia, Antonia, Giulietta, and Stella in the 2007 production.[10]

The Barcarolle

The most famous number in the opera is the "Barcarolle" (Belle nuit, ô nuit d'amour), which opens act 3. Curiously, the aria was not written by Offenbach with Les contes d'Hoffmann in mind. He wrote it as the 'Elves’ Song' in the opera Die Rheinnixen (Les fées du Rhin), which premiered in Vienna on February 8, 1864. Offenbach died with Les contes d'Hoffmann unfinished. Ernest Guiraud completed the scoring and wrote the recitatives for the premiere. He also incorporated this excerpt from one of Offenbach's earlier, long-forgotten operas into the new opera.[11] The Barcarolle inspired the English composer Kaikhosru Shapurji Sorabji to write his Passeggiata veneziana sopra la Barcarola di Offenbach (1955–56). Moritz Moszkowski also wrote a virtuoso transcription of it. The Barcarolle has been incorporated into many films, including Life Is Beautiful and Titanic. It also provided the tune for Elvis Presley's rendition of the song "Tonight Is So Right For Love" in the film G.I. Blues (1960).

Recordings

Main article: The Tales of Hoffmann discographyFilm

- Hoffmanns Erzählungen (1916) a silent German film adaptation directed by Richard Oswald.

- The Tales of Hoffmann (1951) a British film adaptation written, produced and directed by Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger.

References

- Notes

- ^ Newman E. More Opera Nights. Putnam, London, 1954.

- ^ "Der Sandmann" had provided the impetus for the ballet libretto of Coppélia (1870) with music by Léo Delibes.

- ^ Lamb, Andrew "Jacques Offenbach". In: New Grove Dictionary of Opera Macmillan, London and New York, 1997.

- ^ a b c d Wolff S. Un demi-siècle d'Opéra-Comique (1900-1950). André Bonne, Paris, 1953.

- ^ a b Keck J-C. Genèse et Légendes. In: Avant-Scène Opéra 235, Les Contes d’Hoffmann. Paris, 2006.

- ^ Noel E & Stoullig E. Les Annales du Théâtre et de la Musique, 19eme édition, 1893. G Charpentier et E Fasquelle, Paris, 1894.

- ^ a b L’œuvre à l’affiche. In: Avant-Scène Opéra 235, Les Contes d’Hoffmann. Paris, 2006.

- ^ Information from AmadeusOnline.net

- ^ Basilica Opera program 1969

- ^ Mary Dibbern, The Tales of Hoffmann: A Performance Guide, Pendragon Press ISBN 1-57647-033-4

- ^ Nicolas Slonimsky, ed. Richard Kassel in Webster's New World Dictionary of Music, MacMillan, 1998, p. 365

External links

- Les contes d'Hoffmann: Free scores at the International Music Score Library Project.

- Les contes d'Hoffmann at Project Gutenberg: libretto of a modified version (as first performed in the USA) in French and English

- Analysis of The Tales of Hoffman in The Ultimate Art, Chap. 13: "The Odd Couple: Offenbach and Hoffmann"

Lewis M. Isaacs (1920). "Tales of Hoffman". Encyclopedia Americana.

Lewis M. Isaacs (1920). "Tales of Hoffman". Encyclopedia Americana.

Categories:- Operas by Jacques Offenbach

- French-language operas

- 1881 operas

- Unfinished operas

- Operas

- Opéra-Comique world premieres

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.