- Aloha Airlines Flight 243

-

Coordinates: 20°53.919′N 156°25.827′W / 20.89865°N 156.43045°W

Aloha Airlines Flight 243

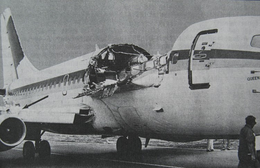

Fuselage of Aloha Airlines Flight 243 after explosive decompression.Accident summary Date April 28, 1988 Type Explosive decompression caused by fatigue failure Site Kahului, Hawaii Passengers 90 Crew 5 Injuries 65 Fatalities 1 Survivors 94 Aircraft type Boeing 737-200 Operator Aloha Airlines Tail number N73711 Flight origin Hilo International Airport (ITO) Destination Honolulu International Airport (HNL) Aloha Airlines Flight 243 (AQ 243, AAH 243) was a scheduled Aloha Airlines flight between Hilo and Honolulu in Hawaii. On April 28, 1988, a Boeing 737-200 serving the flight suffered extensive damage after an explosive decompression in flight, but was able to land safely at Kahului Airport on Maui. The only fatality was flight attendant C.B. Lansing who was blown out of the airplane. Another 65 passengers and crew were injured.

The safe landing of the aircraft despite the substantial damage inflicted by the decompression established Aloha Airlines Flight 243 as a significant event in the history of aviation, with far-reaching effects on aviation safety policies and procedures.

Contents

Details

The aircraft, Queen Liliuokalani (registration number N73711, named after Liliuokalani), took off from Hilo International Airport (PHTO) at 13:25 HST on 28 April 1988, bound for Honolulu (PHNL). There were 90 passengers and five crew members on board. No unusual occurrences were reported during the take-off and climb.[1]

Around 13:48, as the aircraft reached its normal flight altitude of 24,000 feet (7,300 m) about 23 nautical miles (43 km) south-southeast of Kahului, a small section on the left side of the roof ruptured. The resulting explosive decompression tore off a large section of the roof, consisting of the entire top half of the aircraft skin extending from just behind the cockpit to the fore-wing area.[2]

As part of the design of the 737, stress may be alleviated by controlled area breakaway zones. The intent was to provide controlled depressurization that would maintain the integrity of the fuselage structure. The age of the plane and the condition of the fuselage (that had corroded and was stressing the rivets beyond their designed capacity) appear to have conspired to render the design a part of the problem; when that first controlled area broke away, according to the small rupture theory, the rapid sequence of events resulted in the failure sequence. This has been referred to as a zipper effect.

First Officer Madeline "Mimi" Tompkins' head was jerked back during the decompression, and she saw cabin insulation flying around the cockpit. Captain Robert Schornstheimer looked back and saw blue sky where the first class cabin's roof had been. Tompkins immediately contacted Air Traffic Control on Maui to declare mayday, switching duties with Captain Schornstheimer, who from this point on, took over control of the plane, as it is usually customary for the Captain to take over a flight that enters a state of emergency.

At the time of the decompression, the chief flight attendant, Clarabelle "C.B." Lansing, was standing at seat row 5 collecting drink cups from passengers. According to passengers' accounts, Lansing was blown out through a hole in the side of the airplane by the greater air pressure remaining in the cabin.

Flight attendant Michelle Honda, who was standing near rows 15 and 16, was thrown violently to the floor during the decompression. Despite her injuries, she was able to crawl up and down the aisle to assist and calm the terrified passengers. Flight attendant Jane Sato-Tomita, who was at the front of the plane, was seriously injured by flying debris and was thrown to the floor. Passengers held onto her during the descent into Maui.

The explosive decompression severed the electrical wiring from the nose gear to the indicator light on the cockpit instrument panel. As a result, the light did not illuminate when the nose gear was lowered, and the pilots had no way of knowing if it had fully lowered.

Before landing, passengers were instructed to don their life jackets, in case the aircraft did not make it to Kahului.

The crew performed an emergency landing on Kahului Airport's runway 2 at 13:58. Upon landing, the crew deployed the aircraft's emergency evacuation slides and evacuated passengers from the aircraft quickly. First Officer Mimi Tompkins assisted passengers down the evacuation slide.[3] In all, 65 people were reported injured, eight seriously. At the time, Maui had no plan for a disaster of this type. The injured were taken to the hospital by the tour vans from Akamai Tours (now defunct) driven by office personnel and mechanics, since the island only had a couple of ambulances. Air traffic control radioed Akamai and requested as many of their 15 passenger vans as they could spare to go to the airport (less than a mile away) to transport the injured. Two of the Akamai drivers were former medics and established a triage on the runway. The aircraft was a write-off.[4]

Aftermath

Investigation by the United States National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) concluded that the accident was caused by metal fatigue exacerbated by crevice corrosion (the plane operated in a coastal environment, with exposure to salt and humidity).[5][6] The root cause of the problem was failure of an epoxy adhesive used to bond the aluminum sheets of the fuselage together when the B737 was manufactured. Water was able to enter the gap where the epoxy failed to bond the two surfaces together properly, and started the corrosion process.

The age of the aircraft became a key factor in why the damage had been so severe: It was 19 years old at the time of the accident and had sustained a remarkable number of takeoff–landing cycles—89,090, the second most cycles for a plane in the world at the time, and well beyond the 75,000 trips it was designed to sustain. However, several other aircraft operating under similar environments did not exhibit the same phenomenon. A deep and thorough inspection of Aloha Airlines by NTSB revealed that the most extensive and longer "D Check" was performed in several early morning installments, instead of a full uninterrupted maintenance procedure.

According to the official NTSB report of the investigation, Gayle Yamamoto, a passenger, noticed a crack in the fuselage upon boarding the aircraft prior to the ill-fated flight but did not notify anyone.[7] The crack was located aft of the front port side passenger door. The crack was probably due to metal fatigue related to the 89,090 compression and decompression cycles experienced in the short hop flights by Aloha.

As a direct result of this incident, the FAA instituted additional and more thorough mandatory maintenance checks for aging aircraft. In addition, the United States Congress passed the Aviation Safety Research Act of 1988 in the wake of the disaster. This provided for stricter research into probable causes of future airplane disasters.

Both pilots remained with Aloha Airlines. Robert Schornstheimer retired from Aloha Airlines in August 2005. At that time, Madeline Tompkins was still a captain of the airline's Boeing 737-700 aircraft until the airline ceased passenger operations in 2008.

Alternative explanation

Pressure vessel engineer Matt Austin has proposed an alternative hypothesis to explain the disintegration of the fuselage of Flight 243.[7][8] This explanation postulates that initially the fuselage failed as intended and opened a ten-inch square vent. As the cabin air escaped at over 700 mph, flight attendant C.B. Lansing became wedged in the vent instead of being immediately thrown clear of the aircraft. The blockage would have immediately created a pressure spike in the escaping air, a fluid hammer, which tore the jet apart. The NTSB recognizes this hypothesis, but the board does not share the conclusion and maintains its original finding that the fuselage failed at multiple points at once. Former NTSB investigator Brian Richardson, who led the NTSB study of Flight 243, believes the fluid hammer explanation deserves further study.[8]

Memorials

- In 1996, the Lansing Memorial Garden was inaugurated at Honolulu International Airport's Interisland Terminal near the gates formerly used by Aloha Airlines.

CB Lansing in uniform aboard Aloha Airlines aircraft in 1962.

CB Lansing in uniform aboard Aloha Airlines aircraft in 1962.

Dramatizations

- The TV movie Miracle Landing is based on the incident.

- The plot of the novel Airframe references the incident.

- The Discovery Channel/National Geographic Channel series Mayday (called Air Crash Investigations in the United Kingdom and other areas, Air Emergency in the United States), a series about aircraft crashes and incidents, featured this particular flight in the episode "Hanging by a Thread." The episode contained historical footage, recreations of what happened, and interviews with investigators and survivors.

- The History Channel series Secrets of the Black Box also showed historical footage, recreations of what happened, and interviews with investigators and survivors (22 December 2007).

- The Discovery Channel show Mythbusters referenced the flight in its discussion of depressurization in airplanes.

- The Discovery Channel show Moments That Changed Flying aired a segment on the incident in April 2009.

- Spike TV's 1000 Ways To Die in a segment loosely based on how the fuselage broke open and how the victim died.

See also

- Uncontrolled decompression

- List of notable decompression accidents and incidents

- List of accidents and incidents on commercial airliners

- Air safety

- China Airlines Flight 611

References

- ^ NTSB Factual Report (PDF)

- ^ MacPherson, Malcolm (1998). "27". The Black Box: All-New Cockpit Voice Recorder Accounts Of In-flight Accidents. Harper Paperbacks. pp. 157–161. ISBN 978-0-688-15892-7.

- ^ Cooper, Ann Lewis; Rainus, Sharon (2008). "Mimi Tompkins-Aftermath". Stars of the Sky, Legends All: Illustrated Histories of Women Aviation Pioneers. Zenith Press. pp. 138–140. ISBN 978-0-7603-3374-7.

- ^ National Transportation Safety Board (1989). "Excerpts from "Aircraft Accident Report- Aloha Airlines, flight 243, Boeing 737-200,- N73711, near Maui, Hawaii- 28 April 1988". http://www.aloha.net/~icarus/index.htm. Retrieved 22 December 2005.

- ^ Russell, Alan; Lee, Kok Loong (2005). Structure-Property Relations in Nonferrous Metals. Wiley-Interscience. p. 70. ISBN 978-0-471-64952-6.

- ^ "The Aloha incident". http://www.corrosion-doctors.org/Aircraft/Aloha.htm. Retrieved 17 August 2006.

- ^ a b "Hanging by a Thread." Mayday.

- ^ a b The Honolulu Advertiser (2001). "Engineer fears repeat of 1988 Aloha jet accident". http://the.honoluluadvertiser.com/2001/Jan/18/118localnews1.html. Retrieved 6 February 2008.

- NTSB/AAR-89/03 "Aloha Airlines, flight 243, Boeing 737-200, N73711, near Maui, Hawaii, April 28, 1988". National Transportation Safety Board, June 14, 1989.

External links

- Official accident report index page

- Pre-incident photos of N73711

- Miracle Landing at the Internet Movie Database – 1990 TV movie

-

Jul 03 Iran Air Flight 655

Jul 13 British Int'l Helicopters Sikorsky crash

Aug 17 Zia-ul-Haq

Aug 28 Ramstein airshow disaster

Aug 31 Delta Air Lines Flight 1141

Sep 15 Ethiopian Airlines Flight 604Oct 19 Indian Airlines Flight 113

Oct 25 Mexico Learjet 24 crash

Nov 02 LOT Polish Airlines Flight 703

Dec 08 Remscheid A-10 crash

Dec 21 Pan Am Flight 103Incidents resulting in at least 50 deaths shown in italics. Deadliest incident shown in bold smallcaps.Categories:- Aloha Airlines accidents and incidents

- Aviation accidents and incidents in 1988

- Accidents and incidents on commercial airliners in the United States

- Disasters in Hawaii

- In-flight airliner structural failures

- In-flight airliner depressurization

- 1988 in Hawaii

- Accidents and incidents involving the Boeing 737

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.