- City of Illusions

-

City of Illusions

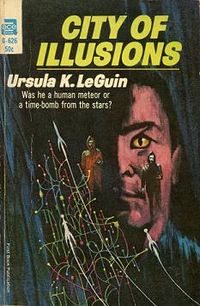

Cover of first edition (paperback)Author(s) Ursula K. Le Guin Cover artist Jack Gaughan Country  United States

United StatesLanguage English Series Hainish Cycle Genre(s) Science fiction Publisher Ace Books Publication date 1967 Media type Print (Paperback) Pages 160 OCLC Number 3516838 Preceded by Planet of Exile Followed by The Left Hand of Darkness City of Illusions is a 1967 post-apocalyptic science fiction novel by Ursula K. Le Guin, set on Earth in the distant future in her Hainish Cycle. City of Illusions is significant because it lays the foundation for the Hainish cycle, a fictional world in which the majority of Ursula K. Le Guin's Science Fiction novels take place.[1]

Contents

Plot introduction

City of Illusions takes place on Earth, also known as Terra, in the year 4370 A.D., twelve hundred years after an enemy named the Shing has broken the power of the League of All Worlds and occupied Earth. The indigenous people of Earth have been reduced in numbers and widely separated, living in highly independent rural communes or nomadic tribal societies. The Shing exercise control over these through various strategies of indirect divide and rule, plus by means of mental control and telepathic deception using a type of Mindspeech known as mind-lying.

Prior to the opening scene, the main character, who is a descendant of the protagonists in Planet of Exile, has been involved in a ship crash, and since the Shing do not believe in killing, has had his memory erased and been abandoned in the forest; this leaves his mind as a blank slate or tabula rasa. As the story begins he must develop a new self identity ex nihilo.

Plot summary

The Man Without Memory

The story starts as a man is found by a small community (housed in one building) in a forest area in eastern North America. He is naked except for a gold ring on one finger, has no memory except of motor skills at a level equivalent to that of a one-year-old and has bizarre, amber, cat-like eyes. The villagers choose to welcome and nurture him, naming him Falk (Yellow). They teach him to speak, educate him about the Earth, and teach him from a book they consider holy, which is Le Guin's "long-translated" version of the Tao Te Ching.[2] Also they teach him about the nature of the never-seen Shing.

The Journey

After six years, Falk is told by the leader of the community that he needs to understand his origins, and as such sets off alone for Es Toch, the city of the Shing in the mountains of western North America. He encounters many obstacles to learning the truth about himself and about the Shing, along with evidence of the barbarism of current human society. Along the way, it is sometimes suggested to him that the image he holds of the Shing is a distorted one; that they respect the idea of 'reverence for life' and are essentially benevolent and non-alien rulers. This suggestion comes from both telepathic animals who remind him for their own self-defense, and from Estrel, a young woman whom Falk meets after being captured by the Basnasska tribe in the great plains. Falk escapes this violent community with Estrel, to reach the city under her guidance.

The Shing

Falk finally reaches Es Toch, where Estrel betrays him into the hands of the Shing and laughs as she does so. He is told that he is part of a crew of a starship of alien/human hybrids from a planet called Werel and meets a young man, Orry, who came with him in the ship. At this point it becomes clear that Estrel is a human collaborator working for the Shing, and that she had been sent to retrieve him from the wilds of so-called Continent 1.

The Shing tell Falk that

- they are in fact humans;

- the conflict between the League and an alien invader never occurred: on the contrary, the League self-destructed through civil war and exploitation;

- the "enemy" is an invention of the Shing rulers themselves to try and ensure through fear that world peace endures under their benevolent, if misunderstood, rule;

- Falk's expedition was attacked by rebels who then erased Falk's memory of his previous self;

- and the Shing, who managed to save only Orry from the rebel attack, now want to restore Falk's previous identity.

Falk however believes that the Shing are non-human liars and that their true intent is to determine for their own purposes, the location of his home-planet.

Restored Memories

Seeing no other way forward, Falk consents to have his memory erased. The mind of the original Werelian, Agad Ramarren, is restored and the Falk personality is apparently destroyed. He emerges as a new person with pre-Falk memories and vastly greater scientific knowledge. Ramarren's first name, Agad, recalls Jakob Agat, one of the chief protagonists of Planet of Exile: of whom he is a descendant. However, thanks to a memory triggering mnemonic device Falk had left for himself (an instruction, through young Orry, to read the beginning of the book he travels with, his translation of the Tao Te Ching), the Falk personality is revived. After some instability Falk's and Ramarren's minds come to coexist. By comparing the knowledge given to them before and after Ramarren's reemergence, the joint minds are able to detect the essential dishonesty of the Shing's rule and the fact that the alien conquerors can lie telepathically. It was this power that had enabled the not very numerous Shing: "exiles or pirates or empire-builders from some distant star", to overthrow the League of All Worlds twelve centuries before.

The Werelians' mental powers are significantly greater than those of their human ancestors. The Shing are inhibited by a cultural dread of killing or being killed and would have no effective defense against any expedition that came forewarned. Still ignorant of the survival of the Falk persona, the Shing hope to send Ramarren back to Werel to present their version of Earth as a happy garden planet prospering under their benign guidance and in no need of outside help. Falk/Ramarren, now fully aware of the brutalized and misruled reality, pretends to accept this, postponing the return journey.

Eventually, while on a pleasure trip to view another part of the Earth, the Shing he is with takes telepathic control of Ramarren but is then overcome by Falk, operating as a separate person. Now controlling the Shing, he makes his escape, manipulating his prisoner to show him where to find the ship that would take him home, and how to program it. (He discovers here that the Shing use a totally alien system of mathematics, quite different from the Cetian mathematics used by all human worlds.) Falk/Ramarren finally leaves for his planet, with Orry and the captive Shing who he has used. He can go back home and organize the liberation of the Earth, but this means cutting himself off from his friends there.

While City of Illusions concludes at this point, Falk/Ramarren's mission apparently succeeds in bringing freedom to the home world of Terra.[3] In The Left Hand of Darkness, Genly Ai comes from Earth and remembers the 'Age of the Enemy' as something dreadful but now past. He also knows of the Werelians, now called Alterrans. The fate of the Shing is not mentioned, either there or in any later book.

Characters

All-Alonio: A solitary, yet profound man who shelters Falk and gives him a "slider," or flying machine.

Estrel: A female agent of the Shing tasked with bringing Falk to Es Toch and convincing him of the beneficial nature of their rule. She wears a necklace of apparent religious significance, but which is in fact a communication device. Estrel eventually suffers an emotional break-down, leading her to turn against the Shing and suffer an unknown fate at their hands.

Falk: A middle aged man who is the protagonist of the story; he appears to suffer from amnesia. As Ramarren he was navigator of the Werel expedition to Earth.

Har Orry: A youth raised and largely brain-washed by the Shing. Other than Falk he is the only known survivor of the Werel expedition. Like Estrel he is used by the Shing to convince Falk of their benign purposes.

Ken Kenyek: A Shing mindhandler, who together with fellow Lords Abundibot and Kradgy, attempts to deceive and manipulate Falk.

Parth: A young human women of the Forest People, who helps re-educate Falk and becomes his lover.

Prince of Kansas: A man who, without force, leads a sophisticated enclave of approximately 200 people living in the wilderness. He is in possession of luxuries such as a great library, domesticated dogs (otherwise extinct in this era), and a complex patterning frame that he uses to foretell Falk's future.

Zove: A father-figure of a family of Forest People whose teaching-by-paradox methods closely resemble those of the sage Laozi.[4]

Publication History

City of Illusions is Le Guin's first novel to appear as an independent paperback, unlike her earlier novels which appeared in the tête-bêche format. It was reissued along with Rocannon's World and Planet of Exile in a 1978 omnibus volume titled Three Hainish Novels, and again in 1996 with the same novels in Worlds of Exile and Illusion.[5]

Literary significance and criticism

Reception

City of Illusions, like its two preceding Hainish novels, received little critical attention when it was published. Subsequently, it has not received as much critical attention as many of Le Guin's other works.[6]

In terms of its place in the development of the canon of science fiction, it has been noted that City of Illusions combines the sensibility of traditional British Science Fiction, images from American genre Science Fiction and anthropological ideas.[7]

Susan Wood, regarding the initial Hainish trilogy as a whole, notes that "innovative and entertaining fictions develop on the solid conceptual basis of human values affirmed"[8] She goes on to point out that philosophical speculation is the most important element of the novel.[9] Dena C. Bain points out that City of Illusions, like Le Guin's novels The Left Hand of Darkness and The Dispossessed, is permeated with a "Taoist mythos."[10]

One science fiction scholar points out that City of Illusions, along with Rocannon's World and Planet of Exile exhibits Le Guin's struggle as an emerging writer to arrive at a plausible, uniquely memorable and straightforward locale for her stories.[11]

The author herself makes several comments about City of Illusions in her introduction to the 1978 hardback edition. Le Guin was excited to use her own translation of the Tao Te Ching. She was also interested in using physical and mental forests in the novel, and in imagining a less populated world, while still holding some type of civilization as a worthwhile, lofty ideal. Specifically she regrets the improbable and flawed depiction of the villains, the Shing, as not convincingly evil.[12]

Themes

Defining and questioning the truth is the central issue of City of Illusions, which holds its roots in the always-truthful "mindspeech" introduced in Planet of Exile and the Shing's ambiguous variation on it, called the "mindlie".[13]

Correspondingly, themes of illusion and ambiguity are central to the novel. The story is as much a post industrial-collapse science fiction tale as it is a mystery tale. It starts with a man with no memory, and with eyes whose appearance suggests he is not human, raising questions as to his true nature: is he human or alien, and is he a tool or a victim of the alien enemy, the Shing. The Shing's nature itself eventually comes into question through his journey. The theme of illusion and ambiguity is present throughout the book - both in terms of behavior (the main female character is initially a friend, then a betrayer and ultimately may be both) and even physical environment (the city Es Toch is a shimmering facade of visual deceptions).[citation needed]

Douglas Barbour points out that light/dark imagery is in an important and common thread that runs through Le Guin's initial Hainish trilogy, tying in closely with Taoism in the Tao-te ching, a book that has special meaning to the main character. Specifically in City of Illusions the main character's story begins and ends in darkness, and among many other similar images, the city of Es Toch is described as a place of awful darkness and bright lights.[14]

Although Le Guin based the location of the city Es Toch on the Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park,[15] James W. Bittner points out that the city of Es Toch, like many of Le Guin's imaginary landscapes, is both an image and a symbol with underlying psychological value and meaning, in this case an underlying chasm.[16] Susan Wood furthers this notion pointing out the city is "built across a chasm in the ground, a hollow place."[17]

Charlotte Spivack points out that City of Illusions includes Le Guin's focus on the concept of contrasts, in particular the need for reconciliation of opposites, a concept related to Taoism, that must take place in Falk's divided mind.[18]

One notable theme of City of Illusions is that of isolation and separation, with the story focusing heavily on one character who does not connect well with other characters.[19]

A minor theme of exploring an oppressive male-dominated culture is present, represented by the misogynistic Bee-Keepers.[20]

It has been suggested that the novel also explores theme of anarchism in the original village and its neighbors, which display communal living.[citation needed]

Objects

The patterning frame, a device which Falk encounters twice, is notable. He first sees a simple one at Zove's house and then later a more complex one that belongs to the Prince of Kansas. The device uses moveable stones on crossing wires as a representation of the physical world; its use as a fortune-telling device, computer, toy, or mystical implement is vague. Scholars have noted that it is a foreshadowing device and used to attain a coexistence of the past, present and future, a notable aspect of Taoism.[21][22]

It has been suggested that the book The Old Canon, the book of the Way, the Tao Te Ching, has talismanic properties in the narrative. As a mere object it is an inspiring book; Falk is given a luxurious copy by Zove before he sets out on his travels. After Falk loses this copy, the Prince of Kansas gives him a replacement from his vast library. At the end of the story, Orry reads a line from the book to help Ramarren reunify his split mind with the mind of Falk.[23]

References

- Notes

- ^ Bernardo, Susan M. & Murphy, Graham J. Ursula K. Le Guin: A Critical Companion, (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2006), pages 18-19.

- ^ Le Guin, Ursula K. City of Illusions Introduction, (New York, NY: Harper & Row, 1978), page vii.

- ^ Wood, Susan, "Discovering Worlds: The Fiction of Ursula K. Le Guin" published in Ursula K. Le Guin (Modern Critical Views), ed. Harold Bloom, (New York, NY: Chelsea House Publishers, 1986) page 190.

- ^ Bain, Dena C., "The Tao Te Ching as Background to the Novels of Ursula K. Le Guin" published in Ursula K. Le Guin (Modern Critical Views), ed. Harold Bloom, (New York, NY: Chelsea House Publishers, 1986) page 213.

- ^ Bernardo, Susan M. & Murphy, Graham J. Ursula K. Le Guin: A Critical Companion, (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2006), page 18.

- ^ Cadden, Mike. Ursula K. Le Guin Beyond Genre: Fiction for Children and Adults, (New York, NY: Routledge, 2005) page 30.

- ^ Bernardo, Susan M. & Murphy, Graham J. Ursula K. Le Guin: A Critical Companion, (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2006), page 16.

- ^ Wood, Susan, "Discovering Worlds: The Fiction of Ursula K. Le Guin" published in Ursula K. Le Guin (Modern Critical Views), ed. Harold Bloom, (New York, NY: Chelsea House Publishers, 1986) page 186.

- ^ Wood, Susan, "Discovering Worlds: The Fiction of Ursula K. Le Guin" published in Ursula K. Le Guin (Modern Critical Views), ed. Harold Bloom, (New York, NY: Chelsea House Publishers, 1986) page 188.

- ^ Bain, Dena C., "The Tao Te Ching as Background to the Novels of Ursula K. Le Guin" published in Ursula K. Le Guin (Modern Critical Views), ed. Harold Bloom, (New York, NY: Chelsea House Publishers, 1986) page 211.

- ^ Sawyer, Andy The Mythic Fantasy of Robert Holdstock: Critical Essays on the Fiction, eds. Morse, Donald E. & Matolcsy, Kalman (London: McFarland & Company, Inc. 2011), page 77.

- ^ Le Guin, Ursula K. City of Illusions Introduction, (New York, NY: Harper & Row, 1978), page vii.

- ^ Bain, Dena C., "The Tao Te Ching as Background to the Novels of Ursula K. Le Guin" published in Ursula K. Le Guin (Modern Critical Views), ed. Harold Bloom, (New York, NY: Chelsea House Publishers, 1986) page 213.

- ^ Barbour, Douglas, "Wholeness and Balance in the Hainish Novels" published in Ursula K. Le Guin (Modern Critical Views), ed. Harold Bloom, (New York, NY: Chelsea House Publishers, 1986) pages 24-25.

- ^ Spivack, Charlotte. Ursula K. Le Guin, (Boston, MA: Twayne Publishers, 1984) page 21.

- ^ Bittner, James W., "Persuading Us to Rejoice and Teaching Us How to Praise: Le Guin's Orsinian Tales" published in Ursula K. Le Guin (Modern Critical Views), ed. Harold Bloom, (New York, NY: Chelsea House Publishers, 1986) page 129.

- ^ Wood, Susan, "Discovering Worlds: The Fiction of Ursula K. Le Guin" published in Ursula K. Le Guin (Modern Critical Views), ed. Harold Bloom, (New York, NY: Chelsea House Publishers, 1986) page 184.

- ^ Spivack, Charlotte. Ursula K. Le Guin, (Boston, MA: Twayne Publishers, 1984) page 14.

- ^ Cadden, Mike. Ursula K. Le Guin Beyond Genre: Fiction for Children and Adults, (New York, NY: Routledge, 2005) pages 30 & 38.

- ^ Spivack, Charlotte. Ursula K. Le Guin, (Boston, MA: Twayne Publishers, 1984) page 20.

- ^ Wood, Susan, "Discovering Worlds: The Fiction of Ursula K. Le Guin" published in Ursula K. Le Guin (Modern Critical Views), ed. Harold Bloom, (New York, NY: Chelsea House Publishers, 1986) page 186.

- ^ Bain, Dena C., "The Tao Te Ching as Background to the Novels of Ursula K. Le Guin" published in Ursula K. Le Guin (Modern Critical Views), ed. Harold Bloom, (New York, NY: Chelsea House Publishers, 1986) page 220.

- ^ Spivack, Charlotte. Ursula K. Le Guin, (Boston, MA: Twayne Publishers, 1984) page 22.

- Bibliography

- Bernardo, Susan M.; Murphy, Graham J. (2006). Ursula K. Le Guin: A Critical Companion (1st ed.). Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0313332258.

- Bloom, Harold, ed (1986). Ursula K. Le Guin (1st ed.). New York, NY: Chelsea House. ISBN 0877546592.

- Cadden, Mike (2005). Ursula K. Le Guin Beyond Genre: Fiction for Children and Adults (1st ed.). New York, NY: Routledge. ISBN 0415995272.

- Le Guin, Ursula K. (1978). City of Illusions With a New Introduction by the Author (hardback ed.). New York, NY: Harper & Row.

- Le Guin, Ursula K. (1978). Three Hainish Novels (1st ed.). Nelson Doubleday.

- Le Guin, Ursula K. (1996). Worlds of Exile and Illusion (1st ed.). New York, NY: Orb. ISBN 0312862114.

- Spivack, Charlotte (1984). Ursula K. Le Guin (1st ed.). Boston, MA: Twayne Publishers. ISBN 0805773932.

Works by Ursula K. Le Guin – (bibliography) Earthsea "The Word of Unbinding" (1964) · "The Finder" (2001) · "Darkrose and Diamond" (1999) · "The Rule of Names" (1964) · "The Bones of the Earth" (2001) · A Wizard of Earthsea (1968) · The Tombs of Atuan (1971) · "On the High Marsh" (2001) · The Farthest Shore (1972) · Tehanu (1990) · "Earthsea Revisioned" (1993) · "Dragonfly" (1997) · Tales from Earthsea (2001) · The Other Wind (2001)Hainish Cycle "Dowry of the Angyar" (1964) · Rocannon's World (1966) · Planet of Exile (1966) · City of Illusions (1967) · The Left Hand of Darkness (1969) · "Winter's King" (1969) · "Vaster Than Empires and More Slow" (1971) · The Dispossessed (1974) · "The Day Before the Revolution" (1974) · The Word for World is Forest (1976) · "The Shobies' Story" (1990) · "Dancing to Ganam" (1993) · "Another Story or A Fisherman of the Inland Sea" (1994) · "The Matter of Seggri" (1994) · "Unchosen Love" (1994) · "Solitude" (1994) · Four Ways to Forgiveness (1995) · "Coming of Age in Karhide" (1995) • "Mountain Ways" (1996) · "Old Music and the Slave Women" (1999) · The Telling (2000)Other fiction

(novels bold)The Lathe of Heaven (1971) · The Wind's Twelve Quarters (1975) · Orsinian Tales (1976) · The Eye of the Heron (1978) · Malafrena (1979) · The Beginning Place (1980) · The Compass Rose (1982) · Always Coming Home (1985) · Buffalo Gals, and Other Animal Presences (1987) · Searoad (1991) · A Fisherman of the Inland Sea (1994) · Unlocking the Air and Other Stories (1996) · The Birthday of the World (2002) · Changing Planes (2003) · Lavinia (2008)Nonfiction The Language of the Night (1979) · Dancing at the Edge of the World (1982) · Lao Tzu: Tao Te Ching (1997) · Steering the Craft (1998) · The Wave in the Mind (2004)Categories:- 1967 novels

- Ekumen novels

- Post-apocalyptic novels

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.