- Niðhad

-

King Niðhad, Níðuðr or Niðung was a cruel king in Germanic legend. He appears as Níðuðr in the Old Norse Völundarkviða, as Niðung in the Þiðrekssaga, and as Niðhad in the Anglo-Saxon poems Deor and Waldere.

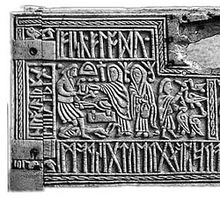

The legend of Níðuðr and Wayland also appears on the Gotlandic Ardre image stone VIII from the 8th century and possibly on the front panel of the 7th century Anglo-Saxon Franks Casket. However, Austin Simmons has recently argued that it is not Niðhad who is depicted, but his daughter Beadohilde (twice).[1]

Contents

Völundarkviða

In Völundarkviða,[2] Níðuðr appears to be a king of Närke (the Njars) and captures Völund. Níðuðr orders Völund hamstrung and imprisoned on the island of Sævarstaðir. There Völund was forced to forge items for the king. Völund's wife's ring was given to the king's daughter, Bodvild, and Níðuðr wore Völund's sword.

For revenge, Völund killed the king's sons when they visited him in secret, fashioned goblets from their skulls, jewels from their eyes, and a brooch from their teeth. He sent the goblets to the king, the jewels to the queen and the brooch to the kings' daughter. When Bodvild took her ring to him to be mended, he took the ring and seduced her, fathering a son and escaping on wings he made.

Þiðrekssaga

Main article: Velents þáttr smiðsIn the Þiðrekssaga,[3] Niðung is the king of Jutland. A master smith named Velent arrived in Niðung's kingdom, and Niðung graciously accepted Velent as a servant at his court. One day Velent had lost Niðung's knife, but he secretly made another one for the king. When Niðung discovered that his knife cut better than it used to, he enquired about this with Velent. The smith lied and said that it was Amilias, the court smith, who had made it.

Suspicious, Niðung put the two smiths to a test. Velent would forge a sword and Amilias an armour, and then Velent was to use the sword trying to kill Amilias who would wear the armour. However, when Velent was to make the sword he discovered that his tools had disappeared. As he suspected the chieftain Regin to be the thief, Velent made a lifelike statue of Regin. Niðung understood that Velent was the master smith Velent himself, and Velent got his tools back.

Velent forged the great sword Mimung and an ordinary sword. When Velent and Amilias began to fight Velent cut Amilias so finely with Mimung that Amilias did not discover that he was cut in half until Velent asked him to shake. Then Amilias fell apart. Niðung then asked for the great sword Mimung, but Velent gave him the ordinary sword, which was a copy of Mimung.

One day during a war expedition Niðung found out that he had forgotten his magic victory stone Siegerstein. Desperately he offered his own daughter to the knight who could bring the stone to him before the next morning. Velent went back and fetched the stone, but another knight wanted to claim the stone and the princess. Velent killed the knight which greatly upset Niðung. Velent had to leave Niðung's kingdom.

Velent later returned in disguise to Niðung's kingdom and gave the daughter a love philter. The plan failed because the princess' magic knife showed her the danger before she had imbibed the potion. Velent then exchanged the knife for an ordinary knife of his own making, but when the princess noticed that the new knife was much better than the old one, the disguised Velent was revealed. Niðung then ordered that Velent's knee tendons be cut as a punishment and Velent was set to work in the smithy.

Wanting revenge, Velent seduced and impregnated the princess and killed Niðung's two sons, making table ware of their bones. Then Velent's brother Egil arrived at the court. Niðung ordered Egil to shoot an apple from the head of his son. He readied two arrows, but succeeded with the first one. Asked by the king what the second arrow was for, he said that had he killed his son with his first arrow, he would have shot the king with the second one. This tale is directly comparable to the legends of William Tell and Palnetoke. Unlike Tell, however, the king does not punish Egil for his openness, but rather commended him for it.

To help his brother, Egil shot birds and collected their feathers, of which Velent made a pair of wings. Velent tied a bladder filled with blood around his waist and flew away. Niðung commanded Egil to shoot his fleeing brother, who hit the bladder, deceiving Niðung, and so Velent got away.

Deor

Depiction of the hamstrung smith Weyland from the front of the Franks Casket.

Depiction of the hamstrung smith Weyland from the front of the Franks Casket.

In the poem Deor there is a stanza which refers to an Old English version of the legend of Welund and his captivity at the court of Nithad:

- Welund him be wurman wræces cunnade,

- anhydig eorlearfoþa dreag,

- hæfde him to gesiþþe sorge ond longaþ,

- wintercealde wræce; wean oft onfond,

- siþþan hine Niðhad onnede legde,

- swoncre seonobendeon syllan monn.

- Þæs ofereode,þisses swa mæg!

- -

- Beadohilde ne wæshyre broþra deaþ

- on sefan swa sarswa hyre sylfre þing,

- þæt heo gearoliceongieten hæfde

- þæt heo eacen wæs;æfre ne meahte

- þriste geþencan,hu ymb þæt sceolde.

- Þæs ofereode,þisses swa mæg![4]

- Welund tasted misery among snakes.

- The stout-hearted hero endured troubles

- had sorrow and longing as his companions

- cruelty cold as winter - he often found woe

- Once Nithad laid restraints on him,

- supple sinew-bonds on the better man.

- That went by; so can this.

- -

- To Beadohilde, her brothers' death was not

- so painful to her heart as her own problem

- which she had readily perceived

- that she was pregnant; nor could she ever

- foresee without fear how things would turn out.

- That went by, so can this.[5]

Waldere

In the Old English fragment known as Waldere, Niðhad is mentioned together with Wayland and Widia in a praise of Mimmung, Waldere's sword that Weyland had made.

- ....... ... me ce bæteran

- buton ðam anum, ðe ic eac hafa,

- on stanfate stille gehided.

- Ic wat þæt hit dohte Ðeodric Widian

- selfum onsendon, ond eac sinc micel

- maðma mid ði mece, monig oðres mid him

- golde gegirwan, iulean genam,

- þæs ðe hine of nearwum Niðhades mæg,

- Welandes bearn, Widia ut forlet,

- ðurh fifela geweald forð onette.

- ........... a better sword

- except the one that I have also in

- its stone-encrusted scabbard laid aside.

- I know that Theodric thought to Widia's self

- to send it and much treasure too,

- jewels with the blade, many more besides,

- gold-geared; he received reward

- when Nithhad's kinsman, Widia, Welund's son,

- delivered him from durance;

- through press of monsters hastened forth.'[6]

Notes and references

- ^ A recent paper on the Franks Casket, resolving many long-standing artistic and linguistic problems.

- ^ The Lay of Völund, in translation by Henry A. Bellows, at Northvegr.

- ^ A summary of Þiðrekssaga at a personal site.

- ^ Deor at the site of the society Ða Engliscan Gesiþas.

- ^ Modern English translation by Steve Pollington, Published in Wiðowinde 100, at the site of the society Ða Engliscan Gesiþas.

- ^ Translated by Louis Rodrigues.

External links

- [1] (Austin Simmons, The Cipherment of the Franks Casket)

- A presentation of the Weyland legend on the Franks Casket.

Categories:- Heroes in Norse myths and legends

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.