- DuSable Museum of African American History

-

Coordinates: 41°47′32″N 87°36′26″W / 41.792111°N 87.607306°W

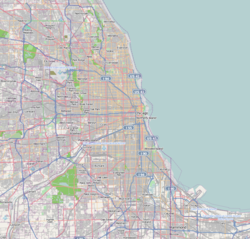

DuSable Museum of African American History  Location within the Chicago metropolitan area.

Location within the Chicago metropolitan area.Established February 16, 1961

(current location since 1973)Location 740 East 56th Place

Chicago, Illinois 60637

United States

Director Antoinette Wright Website www.dusablemuseum.org The DuSable Museum of African American History is the first and oldest museum dedicated to the study and conservation of African American history, culture, and art. It was founded in 1961 by Dr. Margaret Taylor-Burroughs (sometimes Margaret Burroughs or Margaret Goss Burroughs), her husband Charles Burroughs, Gerard Lew, and others. Dr. Taylor-Burroughs and other founders established the museum to celebrate black culture, then overlooked by most museums and academic establishments. It is located at 740 E. 56th Place at the corner of Cottage Grove Avenue on the South Side of Chicago in the Washington Park community area.

Contents

History

The DuSable Museum was originally chartered on February 16, 1961.[1] Its origins as the Ebony Museum of Negro History and Art began following the work of Margaret and Charles Burroughs to correct the perceived omission of black history and culture in the education establishment.[2][3] The museum was originally located on the ground floor of the Burroughs' home at 3806 S. Michigan Avenue.[2][4][5] In 1968, the museum was renamed for Jean Baptiste Point du Sable, a Haitian fur trader and the first non-Native-American permanent settler in Chicago.[6][7] During the 1960s, the museum and the South Side Community Art Center, which was located across the street, founded by Taylor-Burroughs and dedicated by Eleanor Roosevelt,[8] formed an African American cultural corridor.[6] This original museum site had previously been a boarding house for African American railroad workers.[6]

The DuSable Museum quickly filled a void caused by limited cultural resources then available to African Americans in Chicago. It became an educational resource for African American history and culture and a focal point in Chicago for black social activism. The museum has hosted political fundraisers, community festivals, and various events serving the black community. The museum's model has been emulated in numerous other cities around the country, including Boston, Los Angeles, and Philadelphia.[6]

The Harold Washington Wing

In 1973, the Chicago Park District donated the usage of a park administration building in Washington Park as the site for the museum.[3][4] The current location once served as a lockup facility for the Chicago Police Department.[4] In 1993, the museum expanded with the addition of a new wing named in honor of the late Mayor Harold Washington,[3] the first African-American mayor of Chicago.[9] In 2004, the original building became a contributing building to the Washington Park United States Registered Historic District which is a National Register of Historic Places listing.[10][11]

The DuSable Museum is the oldest and largest caretaker of African American culture in the United States. Over its long history, it has expanded as necessary to reflect the increased interest in black culture.[12] This willingness to adapt has allowed it to survive while other museums faltered due to a weakening economy and decreased public support.[13] The museum was the eighth one located on Park District land.[3] Although it focuses on exhibiting African American culture, it is one of several Chicago museums that celebrates Chicago's ethnic and cultural heritage.[14]

Antoinette Wright, director of the DuSable Museum, has said that African American art has grown out of a need for the culture to preserve its history orally and in art due to historical obstacles to other forms of documentation. She also believes that the museum serves as a motivational tool for members of a culture that has experienced extensive negativity.[15] In the 1980s, African American museums such as the DuSable endured the controversy of whether negative aspects of the cultural history should be memorialized.[16] In the 1990s, the African American genre of museum began to flourish despite financial difficulties.[15]

Collection

The new wing contains a permanent exhibit on Washington with memorabilia, personal effects and surveys highlights of his political career.[4] The museum also serves as the city's primary memorial to du Sable.[3] Highlights of its collection include the desk of activist Ida B. Wells and the violin of poet Paul Laurence Dunbar.[17]

According to a Frommer's review published in The New York Times, the museum has a collection of 13,000 artifacts, books, photographs, art objects, and memorabilia.[4] The DuSable collection has come largely from private gifts. It has United States slavery-era relics, nineteenth- and twentieth-century artifacts, and archival materials, including the diaries of sea explorer Captain Harry Dean. The DuSable collection includes works from scholar W. E. B. Du Bois, sociologist St. Clair Drake, and poet Langston Hughes. The African American art collection contains selections from the South Side Community Art Center students Charles White, Archibald Motley, Jr., Charles Sebree, and Marion Perkins, as well as numerous New Deal Works Progress Administration period and 1960s Black Arts Movement works. The museum also owns prints and drawings by Henry O. Tanner, Richmond Barthé, and Romare Bearden, and has an extensive collection of books and records pertaining to African and African American history and culture.[6]

Facilities

The original north entrance contains the main lobby of the museum and features the Thomas Miller mosaics, which honor the institution's founders. The building was designed c.1915 by D.H. Burnham and Company to serve as the South Park Administration Building in Washington Park on the city's south side.[3] The new wing is 25,000 square feet (2,300 m2). The museum has a 466-seat auditorium, which is part of the new wing, that hosts community-related events, such as a jazz and blues music series, poetry readings, film screenings, and other cultural events. The museum also has a gift shop and a research library.[4] As of 2001, the museum operated with a US$2.7 million budget, compared to a $55.7M budget for the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.[15] The museum's funding is partially dependent upon a Chicago Park District tax levy.[6]

After the 1993 expansion of the new wing, the museum contained 50,000 square feet (4,600 m2) of exhibition space. The $4 million expansion was funded by a $2 million matching funds grant from city and state officials.[1]

See also

- Barzillai Lew Lew Family

- List of museums focused on African Americans

- List of museums and cultural institutions in Chicago

References

- ^ a b "Tanqueray salutes the DuSable Museum - DuSable Museum of African-American History, Chicago, Illinois". Ebony. Johnson Publishing Company. February 1993. http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m1077/is_/ai_13365349. Retrieved 2009-01-13.

- ^ a b "Margaret Burroughs Biography". The HistoryMakers. 2000-06-12. http://www.thehistorymakers.com/biography/biography.asp?bioindex=39. Retrieved 2008-04-15.

- ^ a b c d e f "About DuSable Museum". DuSable Museum of African American History. Archived from the original on April 18, 2008. http://web.archive.org/web/20080418062532/http://www.dusablemuseum.org/g/about/. Retrieved 2008-04-15.

- ^ a b c d e f "Chicago Attractions: DuSable Museum of African-American History". The New York Times. The New York Times Company. http://travel.nytimes.com/travel/guides/north-america/united-states/illinois/chicago/attraction-detail.html?vid=1154654606497. Retrieved 2009-01-04.

- ^ "DuSable Museum of African-American History". Chicago Tribune. http://www.chicagotribune.com/topic/arts-culture/culture/dusable-museum-of-african-american-history-PLCUL000143.topic. Retrieved 2009-01-04.

- ^ a b c d e f Dickerson, Amina J. (2005). "DuSable Museum". Encyclopedia of Chicago. Chicago History Museum. http://www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org/pages/398.html. Retrieved 2008-04-15.

- ^ Wade, Betsy (1991-07-14). "Practical Traveler; Tracing the Trail Of Black History". The New York Times. The New York Times Company. http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9D0CEFDC173DF937A25754C0A967958260. Retrieved 2009-01-27.

- ^ "South Side Community Art Center". Encyclopedia of Chicago. Chicago History Museum. 2005. http://www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org/pages/73.html. Retrieved 2009-01-04.

- ^ Johnson, Dirk (1987-11-26). "Chicago's Mayor Washington Dies After a Heart Attack in His Office". The New York Times. The New York Times Company. http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9B0DE1DC1630F935A15752C1A961948260. Retrieved 2009-01-27.[dead link]

- ^ Bachrach, Julia Sniderman (2004-07-02). "National Register of Historic Places Registration Form: Washington Park" (PDF). United States Department of the Interior/National Park Service. http://gis.hpa.state.il.us/hargis/PDFs/223353.pdf. Retrieved 2009-04-01.

- ^ "Illinois - Cook County - Historic Districts". National Register of Historic Places. http://www.historicdistricts.com/IL/Cook/districts.html. Retrieved 2009-04-01.

- ^ Rotenberk, Lori (1992-02-04). "DuSable Museum to get new look". Chicago Sun-Times. Sun-Times Media Group. http://docs.newsbank.com/openurl?ctx_ver=z39.88-2004&rft_id=info:sid/iw.newsbank.com:NewsBank:CSTB&rft_val_format=info:ofi/fmt:kev:mtx:ctx&rft_dat=0EB37396DDDA7995&svc_dat=InfoWeb:aggregated5&req_dat=0D0CB579A3BDA420. Retrieved 2009-01-27.

- ^ Jackson, Cheryl V. (2005-02-01). "DuSable plans expansion as others falter". Chicago Sun-Times. Sun-Times Media Group. http://docs.newsbank.com/openurl?ctx_ver=z39.88-2004&rft_id=info:sid/iw.newsbank.com:NewsBank:CSTB&rft_val_format=info:ofi/fmt:kev:mtx:ctx&rft_dat=10831ED67B108B9E&svc_dat=InfoWeb:aggregated5&req_dat=0D0CB579A3BDA420. Retrieved 2009-01-27.

- ^ Schmidt, William E. (1990-11-04). "What's Doing In; Chicago". The New York Times. The New York Times Company. http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9C0CE6D81E3DF937A35752C1A966958260&sec=&spon=&pagewanted=2. Retrieved 2009-01-04.

- ^ a b c Kinzer, Stephen (2001-02-22). "Arts in America; A Struggle to Be Seen". The New York Times. The New York Times Company. http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9C06EEDC1439F931A15751C0A9679C8B63. Retrieved 2009-01-04.[dead link]

- ^ Williams, Lena (1988-12-08). "Black Memorabilia: The Pride and the Pain". The New York Times. The New York Times Company. http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=940DEFDC1338F93BA35751C1A96E948260. Retrieved 2009-01-04.

- ^ Wade, Betsy (1991-07-14). "Practical Traveler; Tracing the Trail Of Black History". The New York Times. The New York Times Company. http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9D0CEFDC173DF937A25754C0A967958260&sec=&spon=&pagewanted=2. Retrieved 2009-01-04.

External links

City of Chicago Chicago metropolitan area · State of Illinois · United States of America Architecture · Beaches · Climate · Colleges and Universities · Community areas · Culture · Demographics · Economy · Flag · Freeways · Geography · Government · History · Landmarks · Literature · Media · Music · Neighborhoods · Parks · Public schools · Skyscrapers · Sports · Theatre · Transportation

Category ·

Category ·  Portal

PortalWashington Park Bud Billiken Parade and Picnic • DuSable Museum of African American History • Fountain of Time • Schulze Baking Company Plant • Washington Park Race Track • Washington Park (Chicago park) • Washington Park Subdivision • Washington Park Court DistrictCategories:- African American museums in Illinois

- Museums established in 1961

- Museums in Chicago, Illinois

- Visitor attractions in Chicago, Illinois

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.