- Either/Or

-

For the Elliott Smith album, see Either/Or (album). For the game show, see Either/Or (TV series).

Either/Or

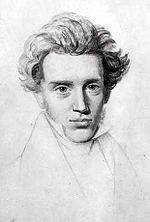

Title page of the original Danish edition from 1843.Author(s) Søren Kierkegaard Original title Enten-Eller Country Denmark Language Danish Series First authorship (Pseudonymous) Genre(s) Philosophy Publisher University bookshop Reitzel, Copenhagen Publication date February 20, 1843 Published in

English1944 - First Translation Pages 800+ Followed by Two Upbuilding Discourses, 1843 Published in two volumes in 1843, Either/Or (original Danish title: Enten ‒ Eller) is an influential book written by the Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard, exploring the aesthetic and ethical "phases" or "stages" of existence.

Either/Or portrays two life views, one consciously hedonistic, the other based on ethical duty and responsibility. Each life view is written and represented by a fictional pseudonymous author, the prose of the work depending on the life view being discussed. For example, the aesthetic life view is written in short essay form, with poetic imagery and allusions, discussing aesthetic topics such as music, seduction, drama, and beauty. The ethical life view is written as two long letters, with a more argumentative and restrained prose, discussing moral responsibility, critical reflection, and marriage.[1] The views of the book are not neatly summarized, but are expressed as lived experiences embodied by the pseudonymous authors. The book's central concern is the primal question asked by Aristotle, "How should we live?"[2]

Contents

Historical context

After writing and defending his dissertation The Concept of Irony with Continual Reference to Socrates (1841), Kierkegaard left Copenhagen in October 1841 to spend the winter in Berlin. The main purpose of this visit was to attend the lectures by the German philosopher Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling, who was an eminent figure at the time. The lectures turned out to be a disappointment for many in Schelling's audience, including Mikhail Bakunin and Friedrich Engels, and Kierkegaard described it as "unbearable nonsense".[3] During his stay, Kierkegaard worked on the manuscript for Either/Or, took daily lessons to perfect his German and attended operas and plays, particularly by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and Johann Wolfgang Goethe. He returned to Copenhagen in March 1842 with a draft of the manuscript, which was completed near the end of 1842 and published in February 1843.

According to a journal entry from 1846, Either/Or "was written lock, stock, and barrel in eleven months",[4][5] although a page from the "Diapsalmata" section in the 'A' volume was written before that time.

The title Either/Or is an affirmation of Aristotelian logic, particularly

- Law of identity (A = A; a thing is identical to itself)

- Law of excluded middle (either A or not-A; a thing is either something or not that thing, no third option)

- Law of non-contradiction. (not both A and not-A; a thing cannot be both true and not true in the same instant)

In Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel's work, The Science of Logic (1812), Hegel had criticized Aristotle's laws of classical logic for being static, rather than dynamic and becoming, and had replaced it with his own dialectical logic. Hegel formulated addendums for Aristotle's laws:[6][7][8][9][10]

- Law of identity is inaccurate because a thing is always more than itself

- Law of excluded middle is inaccurate because a thing can be both itself and many others

- Law of non-contradiction is inaccurate because everything in existence is both itself and not itself

Kierkegaard argues that Hegel's philosophy dehumanized life by denying personal freedom and choice through the neutralization of the 'either/or'. The dialectic structure of becoming renders existence far too easy, in Hegel's theory, because conflicts are eventually mediated and disappear automatically through a natural process that requires no individual choice other than a submission to the will of the Idea or Geist. Kierkegaard saw this as a denial of true selfhood and instead advocated the importance of personal responsibility and choice-making.[9][10]

Kierkegaard discussed this in his 1846 book, Concluding Unscientific Postscript, Vol. 1:

Ethics must denounce all the jubilation heard in our day over having surmounted reflection. Who is it who is supposed to have surmounted reflection? An existing person. But existence itself is the sphere of reflection, and an existing person is in existence and therefore in reflection-how, then, does he go about surmounting it? It is not difficult to perceive that in a certain sense the principle of identity is higher, is the basis of the principle of contradiction. But the principle of identity is only the boundary; it is like the blue mountains, like the line the artist calls the base line-the drawing is the main thing. Therefore, identity is the terminus a quo [point from which] but not ad quem [to which] for existence. An existing person can maxime arrive at and continually arrive at identity by abstracting from existence. But since ethics regards every existing person as its bond servant, it absolutely forbids him to commence this abstracting at any moment. Instead of saying that the principle of identity or, as Hegel so often says, let it “go to the ground.” Mediation wants to make existence easier for the existing person by omitting an absolute relation to an absolute goal or end. The practice of the absolute distinction makes like absolutely strenuous, especially when one must also remain in the finite and simultaneously relate oneself absolutely to the absolute end or goal and relatively to relative ends. But there is nevertheless a tranquility and restfulness in all this strenuousness, because it is no contradiction to relate oneself absolutely to the absolute end or goal, that is, with all one’s might and in renunciation of everything else, but it is the absolute reciprocity in like for like. In other words, the agonizing self-contradiction of worldly passion results from the individual’s relating himself absolutely to a relative end. Thus vanity, avarice, envy, etc. are essentially lunacy, because the most common expression of lunacy is just this-to relate oneself absolutely to the relative-and esthetically it is to be interpreted comically, since the comic always lies in contradiction. It is demented for a being who is eternally structured to apply all his power to grasp the perishable, to hold fast to the changeable, and to believe that he has won everything when he has won this nothing-he is duped. The perishable is nothing when it is past, and its essence is to be past, as swiftly as the moment of sensual pleasure, which is the furthest distance from the eternal-a moment in time filled with emptiness. p. 421-422

Structure

The book is the first of Kierkegaard's works written pseudonymously, a practice he employed during the first half of his career.[11][12] In this case, four pseudonyms are used:

- "Victor Eremita" - the fictional compiler and editor of the texts, which he claims to have found in an antique escritoire.

- "A" - the moniker given to the fictional author of the first text ("Either") by Victor Eremita, whose real name he claims not to have known.

- "Judge Vilhelm" - the fictional author of the second text ("Or").

- "Johannes" - the fictional author of a section of 'Either' titled "The Diary of a Seducer".[1]

Either

"Something marvelous happened to me. I was transported to the seventh heaven. There sat all the gods assembled. As a special dispensation, I was granted the favor of making a wish. "Do you wish for youth," said Mercury, "or for beauty, or power, or a long life; or do you wish for the most beautiful woman, or any other of the many fine things we have in our treasure chest? Choose, but only one thing!" For a moment I was bewildered; then I addressed the gods, saying: "My esteemed contemporaries, I choose one thing — that I may always have the laughter on my side." Not one god said a word; instead, all of them began to laugh. From that I concluded that my wish was granted and decided that the gods knew how to express themselves with good taste: for it would indeed have been inappropriate to reply solemnly: It is granted to you." A; Diapsalmata (Hong Translation, slightly abbreviated) The first volume, the "Either", describes the "aesthetic" phase of existence. It contains a collection of papers, found by 'Victor Eremita' and written by 'A', the "aesthete."[3][10]

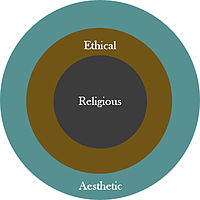

The aesthete, according to Kierkegaard's model, will eventually find himself in "despair", a psychological state (explored further in Kierkegaard's The Concept of Anxiety and The Sickness Unto Death) that results from a recognition of the limits of the aesthetic approach to life. Kierkegaard's "despair" is a somewhat analogous precursor of existential angst. The natural reaction is to make an eventual "leap" to the second phase, the "ethical," which is characterized as a phase in which rational choice and commitment replace the capricious and inconsistent longings of the aesthetic mode. Ultimately, for Kierkegaard, the aesthetic and the ethical are both superseded by a final phase which he terms the "religious" mode. This is introduced later in Fear and Trembling.

Diapsalmata

The first section of Either is a collection of many tangential aphorisms, epigrams, anecdotes and musings on the aesthetic mode of life. The word 'diapsalmata' is related to 'psalms', and means "refrains". It contains some of Kierkegaard's most famous and poetic lines, such as "What is a poet?", "Freedom of Speech" vs. "Freedom of Thought", the "Unmovable chess piece", the tragic clown, and the laughter of the gods.[13]

The Immediate Stages of the Erotic, or Musical Erotic

An essay discussing the idea that music expresses the spirit of sensuality. 'A' evaluates Mozart's The Marriage of Figaro, The Magic Flute and Don Giovanni, as well as Goethe's Faust.

Essays read before the Symparanekromenoi

The next three sections are essay lectures from 'A' to the 'Symparanekromenoi', a club or fellowship of the dead. The first essay, which discusses ancient and modern tragedy, is called the "Ancient Tragical Motif as Reflected in the Modern".

The second essay, called "Shadowgraphs: A Psychological Pastime", discusses modern heroines, including Mozart's Elvira and Goethe's Gretchen.

The third essay, called "The Unhappiest One", discusses the hypothetical question: "who deserves the distinction of being unhappier than everyone else?"

The First Love

In this volume Kierkegaard examines the concept of 'First Love' as a pinnacle for the aestheticist, using his idiosyncratic concepts of 'closedness' (indesluttethed in Danish) and the 'demonic' (demoniske) with reference to Eugène Scribe.

Crop Rotation: An Attempt at a Theory of Social Prudence

In agriculture, one rotates the crop to keep the soil fertile and full of nutrients. Crop Rotation in Either/Or refers to the aesthete's need to keep life "interesting", to avoid both boredom and the need to face the responsibilities of an ethical life.

Diary of a Seducer

Written by 'Johannes the Seducer', this volume illustrates how the aesthete holds the "interesting" as his highest value and how, to satisfy his voyeuristic reflections, he manipulates his situation from the boring to the interesting. He will use irony, artifice, caprice, imagination and arbitrariness to engineer poetically satisfying possibilities; he is not so much interested in the act of seduction as in willfully creating its interesting possibility.

Or

"Do not interrupt the flight of your soul; do not distress what is best in you; do not enfeeble your spirit with half wishes and half thoughts. Ask yourself and keep on asking until you find the answer, for one may have known something many times, acknowledged it; one may have willed something many times, attempted it—and yet, only the deep inner motion, only the heart's indescribable emotion, only that will convince you that what you have acknowledged belongs to you, that no power can take it from you—for only the truth that builds up is truth for you." Judge Vilhelm; Ultimatium (Hong Translation) The second volume represents the ethical stage. Victor Eremita found a group of letters from a retired Judge Vilhelm or William, another pseudonymous author, to 'A', trying to convince 'A' of the value of the ethical stage of life by arguing that the ethical person can still enjoy aesthetic values. The difference is that the pursuit of pleasure is tempered with ethical values and responsibilities.

- "The Aesthetic Validity of Marriage": The first letter is about the aesthetic value of marriage and defends marriage as a way of life.

- "Equilibrium between the Aesthetic and the Ethical in the Development of Personality": The second letter concerns the more explicit ethical subject of choosing the good, or one's self, and of the value of making binding life-choices.

- "Ultimatium": The volume ends in a discourse on the Upbuilding in the Thought that: against God we are always in the wrong.

Introducing the ethical stage it is moreover unclear if Kierkegaard acknowledges an ethical stage without religion. Freedom seems to denote freedom to choose the will to do the right and to denounce the wrong in a secular, almost Kantian style. However, remorse (angeren) seems to be a religious category specifically related to the Christian concept of deliverance.[14]

Discourses and Sequel

Along with this work, Kierkegaard published, under his own name, two upbuilding discourses[15] on May 16, 1843 intended to complement Either/Or, "The Expectancy of Faith" and "Every Good and Every Perfect Gift is from Above".[16] Kierkegaard also published another discourse during the printing of the second edition of Either/Or in 1849.[17]

In addition to the discourses, one week after Either/Or was published, Kierkegaard published a newspaper article in Fædrelandet, titled "Who Is the Author Of Either/Or?", attempting to create authorial distance from the work, emphasizing the content of the work and the embodiment of a particular way of life in each of the pseudonyms. Kierkegaard, using the pseudonym 'A.F.', writes, "most people, including the author of this article, think it is not worth the trouble to be concerned about who the author is. They are happy not to know his identity, for then they have only the book to deal with, without being bothered or distracted by his personality."[18]

The "Ultimatium" at the end of the second volume of Either/Or hinted at a future discussion of the religious stage. This discussion is included in Stages on Life's Way (1845). The first two sections revisit and refine the aesthetic and ethical stages elucidated in Either/Or, while the third section, Guilty/Not Guilty is about the religious stage.[19]

Themes

See also: Philosophy of Søren KierkegaardThe various essays in Either/Or help elucidate the various forms of aestheticism and ethical existence. Both A and Judge Vilhelm attempt to focus primarily upon the best that their mode of existence has to offer.

Summary of the Stages Aesthetic Ethical Defined by immediacy: the failure to reflect seriously upon the nature of one's way of living Defined by critical reflection: able to make and take moral responsibility and accountability for his life choices Sees the outer existence as more important: The self is entirely subject to external factors Sees the inner existence as more important: The self shapes one's own character, values, inclinations, and personal identity; thus, the self is partially subject to internal factors Accepts passively that one's life is based entirely upon external factors Willing to take active control of one's life Tends to avoid commitments, as they see it as boring Commitments, like friendship and marriage, are cornerstones of a responsible ethical way of existence. Exhaustion of aesthetic pleasure leads to boredom and despair Strives to become a better human being through taking an active role in shaping oneself and one's manner of life. A fundamental characteristic of the aesthete is immediacy. In Either/Or, there are several levels of immediacy explored, ranging from unrefined to refined. Unrefined immediacy is characterized by immediate cravings for desire and satisfaction through enjoyments that do not require effort or personal cultivation (e.g. alcohol, drugs, casual sex, sloth, etc.) Refined immediacy is characterized by planning how best to enjoy life aesthetically. The "theory" of social prudence given in Crop Rotation is an example of refined immediacy. Instead of mindless hedonistic tendencies, enjoyments are contemplated and "cultivated" for maximum pleasure. However, both the refined and unrefined aesthetes still accept the fundamental given conditions of their life, and do not accept the responsibility to change it. If things go wrong, the aesthete simply blames existence, rather than one's self, assuming some unavoidable tragic consequence of human existence and thus claims life is meaningless.[10]

Commitment is an important characteristic of the ethicist. Commitments are made by being an active participant in society, rather than a detached observer or outsider. The ethicist has a strong sense of responsibility, duty, honor and respect for his friendships, family, and career.[10] Judge Vilhelm uses the example of marriage as an example of an ethical institution requiring strong commitment and responsibility. Whereas the aesthete would be bored by the repetitive nature of marriage (e.g. married to one person only), the ethicist believes in the necessity of self-denial (e.g. self-denying unmitigated pleasure) in order to uphold one's obligations.[10]

Interpretation

The extremely nested pseudonymity of this work adds a problem of interpretation. A and B are the authors of the work, Eremita is the editor. Kierkegaard's role in all this appears to be that he deliberately sought to disconnect himself from the points of view expressed in his works, although the absurdity of his pseudonyms' bizarre Latin names proves that he did not hope to thoroughly conceal his identity from the reader. Kierkegaard's Papers first edition VIII(2), B 81 - 89 explain this method in writing. On interpretation there is also much to be found in The Point of View of My Work as an Author.[20]

Existential interpretation

A common interpretation of Either/Or presents the reader with a choice between two approaches to life. There are no standards or guidelines which indicate how to choose. The reasons for choosing an ethical way of life over the aesthetic only make sense if one is already committed to an ethical way of life. Suggesting the aesthetic approach as evil implies one has already accepted the idea that there is a good/evil distinction to be made. Likewise, choosing an aesthetic way of life only appeals to the aesthete, ruling Judge Vilhelm's ethics as inconsequential and preferring the pleasures of seduction. Thus, existentialists see Victor Eremita as presenting a radical choice in which no pre-ordained value can be discerned. One must choose, and through one's choices, one creates what one is.[2]

However, the aesthetic and the ethical ways of life are not the only ways of living. Kierkegaard continues to flesh out other stages in further works, and the Stages on Life's Way is considered a direct sequel to Either/Or.

Kantian interpretation

A recent way to interpret Either/Or is to read it as an applied Kantian text. Scholars for this interpretation include Alasdair MacIntyre[21] and Ronald M. Green.[22] In After Virtue, MacIntyre claims Kierkegaard is continuing the Enlightenment project set forward by Hume and Kant.[23] Green notes several points of contact with Kant in Either/Or:[24]

Summary of Kantian Themes in Either/Or Immanuel Kant Judge Vilhelm "The ethical is the universal" When acting on a maxim of mutual aid, one must mentally "create" a world with its own type of humanity and existence An ethical choice requires one to convert to a "universal man" or model of "essential humanity" "Moral judgments cannot be private or privileging" Universalization of maxims; Distinction between hypothetical and categorical imperatives "earthly love is ... partiality; spiritual love has no partialities" "Ethical laws are universally known and applicable" Derived from a priori principle of reason Criticizes "freethinkers" who attempt to prove ethical relativity "Rationality determines moral protection" Must respect rational beings as "ends in themselves" "[each person] even though he were a hired servant ... has his teleology in himself." "Happiness as a supreme end" Happiness as a universal maxim is unstable as a universal law Private pursuit of happiness is unsociable However, other scholars think Kierkegaard adopts Kantian themes in order to criticize them,[21] while yet others think that although Kierkegaard adopts some Kantian themes, their final ethical positions are substantially different. George Stack argues for this latter interpretation, writing, "Despite the occasional echoes of Kantian sentiments in Kierkegaard's writings (especially in Either/Or), the bifurcation between his ethics of self-becoming and Kant's formalistic, meta-empirical ethics is, mutatis mutandis, complete ... Since radical individuation, specificity, inwardness, and the development of subjectivity are central to Kierkegaard's existential ethics, it is clear, essentially, that the spirit and intention of his practical ethics is divorced from the formalism of Kant."[25]

Biographical interpretation

From a purely literary and historical point of view, Either/Or can be seen as a thinly veiled autobiography of the events between Kierkegaard and his ex-fianceé Regine Olsen. Johannes the Seducer in The Diary of a Seducer treats the object of his affection, Cordelia, much as Kierkegaard treats Regine: befriending her family, asking her to marry him, and breaking off the engagement.[26] Either/Or, then, could be the poetic and literary expression of Kierkegaard's decision between a life of sensual pleasure, as he had experienced in his youth, or a possibility of marriage and what social responsibilities marriage might or ought to entail.[2] Ultimately however, Either/Or stands philosophically independent of its relation to Kierkegaard's life.[27]

Reception

Early reception

Either/Or established Kierkegaard's reputation as a respected author.[28] Henriette Wulff, in a letter to Hans Christian Andersen, wrote, "Recently a book was published here with the title Either/Or! It is supposed to be quite strange, the first part full of Don Juanism, skepticism, et cetera, and the second part toned down and conciliating, ending with a sermon that is said to be quite excellent. The whole book attracted much attention. It has not yet been discussed publicly by anyone, but it surely will be. It is actually supposed to be by a Kierkegaard who has adopted a pseudonym...."[28]

Johan Ludvig Heiberg, a prominent Hegelian, at first criticized the aesthetic section, Either, especially the section on the "Diary of a Seducer", revolted by the aesthetic's actions, saying, "One looks at the book, and the possibility is established. One closes the book and says, 'Enough!' I have had enough of Either, I will not have any of Or." However, Heiberg read Or, which impressed him, saying of it, "... bolts of intellectual lightning ... a rare and highly gifted intellect who, out of a deep well of speculation, has drawn forth the most beautiful ethical views, [and who] laces his argument with a stream of the most piquant wit and humor."[28]

Later reception

Although Either/Or was Kierkegaard's first major book, it was one of his last books translated into English in 1944.[29] Frederick DeW. Bolman, Jr., insisted that reviewers consider the book in this way: "In general, we have a right to discover, if we can, the meaning of a work as comprehensive as Either/Or, considering it upon its own merits and not reducing the meaning so as to fit into the author's later perspective. It occurred to me that this was a service to understanding Kierkegaard, whose esthetic and ethical insights have been much slighted by those enamored of his religion of renunciation and transcendence. ... Kierkegaard's brilliance seems to me to be showing that while goodness, truth, and beauty can not speculatively be derived one from another, yet these three are integrally related in the dynamics of a healthy character structure".[30]

Thomas Henry Croxall was impressed by 'As thoughts on music in the essay, "The Immediate Stages of the Erotic, or Musical Erotic". Croxall argues that "the essay should be taken seriously by a musician, because it makes one think, and think hard enough to straighten many of one's ideas; ideas, I mean, not only on art, but on life" and goes on to discuss the psychological, existential, and musical value of the work.[31]

The Diary of a Seducer by itself, is a provocative novella, and has been reproduced separately from Either/Or several times.[32][33][34][35] John Updike said of the Diary, "In the vast literature of love, The Seducer's Diary is an intricate curiosity – a feverishly intellectual attempt to reconstruct an erotic failure as a pedagogic success, a wound masked as a boast".[35]

In contemporary times, Either/Or received new life as a grand philosophical work with the publication of Alasdair MacIntyre's After Virtue, where MacIntyre situates Either/Or as an attempt to capture the Enlightenment spirit set forth by David Hume and Immanuel Kant. After Virtue renewed Either/Or as an important ethical text in the Kantian vein, as mentioned previously. Although MacIntyre accuses Victor Eremita of failing to provide a criterion for one to adopt an ethical way of life, many scholars have since replied to MacIntyre's accusation in Kierkegaard After MacIntyre.[21][36]

References

Primary references

- Either/Or: A Fragment of Life. Translated by Alastair Hannay, Abridged Version. Penguin, 1992, ISBN 9780140445770 (Hannay)

- Either/Or. Translated by David F. Swenson and Lillian Marvin Swenson. Volume I. Prinecton, 1959, ISBN 0691019762 (Swenson)

- Kierkegaard's Writings, III, Part I: Either/Or. Part I. Translated by Howard and Edna Hong. Princeton, 1988, ISBN 9780691020419 (Hong)

- Kierkegaard's Writings, IV, Part II: Either/Or. Part II. Translated by Howard and Edna Hong. Princeton, 1988, ISBN 9780691020426 (Hong)

Secondary references and notes

- ^ a b Kierkegaard, Søren. The Essential Kierkegaard, edited by Howard and Edna Hong. Princeton, ISBN 0-691-01940-1

- ^ a b c Warburton, Nigel. Philosophy: The Classics, 2nd edition. Routledge, ISBN 0-415-23998-2

- ^ a b Chamberlin, Jane and Jonathan Rée. The Kierkegaard Reader. Blackwell, Oxford, 0-631-20467-9

- ^ Søren Kierkegaard, Hong and Hong (ed.) Soren Kierkegaard's Journals and Papers, Volume 5: Autobiographical, §5931 (p. 340)

- ^ Søren Kierkegaard, Hong and Hong (ed.) Either/Or Volume 1, Historical Introduction, p. vii

- ^ Hegel's Science of Logic

- ^

Hegel's Remarks § 883 & 884"From this it is evident that the law of identity itself, and still more the law of contradiction, is not merely of analytic but of synthetic nature. For the latter contains in its expression not merely empty, simple equality-with-self, and not merely the other of this in general, but, what is more, absolute inequality, contradiction per se. But as has been shown, the law of identity itself contains the movement of reflection, identity as a vanishing of otherness. What emerges from this consideration is, therefore, first, that the law of identity or of contradiction which purports to express merely abstract identity in contrast to difference as a truth, is not a law of thought, but rather the opposite of it; secondly, that these laws contain more than is meant by them, to wit, this opposite, absolute difference itself."

- ^

Hegel's Remarks § 952 - 954"The law of the excluded middle is also distinguished from the laws of identity and contradiction ... the latter of these asserted that there is nothing that is at once A and not-A. It implies that there is nothing that is neither A nor not-A, that there is not a third that is indifferent to the opposition. But in fact the third that is indifferent to the opposition is given in the law itself, namely, A itself is present in it. This A is neither +A nor -A, and is equally well +A as -A. The something that was supposed to be either -A or not A is therefore related to both +A and not-A; and again, in being related to A, it is supposed not to be related to not-A, nor to A, if it is related to not-A. The something itself, therefore, is the third which was supposed to be excluded. Since the opposite determinations in the something are just as much posited as sublated in this positing, the third which has here the form of a dead something, when taken more profoundly, is the unity of reflection into which the opposition withdraws as into ground."

- ^ a b Beiser, Frederick C. The Cambridge Companion to Hegel. Cambridge, ISBN 0521387116

- ^ a b c d e f Watts, Michael. Kierkegaard. Oneworld, ISBN 1851683178

- ^ Magill, Frank N. Masterpieces of World Philosophy. HarperCollins, ISBN 0-06-270051-0

- ^ Gardiner, Patrick. Kierkegaard: Past Masters. Oxford, ISBN 978-0-19-287642-3

- ^ Oden, Thomas C. Parables of Kierkegaard. Princeton University Press, ISBN 9780691020532.

- ^ Kierkegaard, Søren. Samlede Vaerker. (2), II, p. 190. 1962-1964.

- ^ Religious works penned under his own name. Commentary on Kierkegaard, D. Anthony Storm,[1]

- ^ Kierkegaard, Søren. Eighteen Upbuilding Discourses. Princeton, ISBN 0-691-02087-6.

- ^ Collected by Princeton University Press in Eighteen Upbuilding Discourses

- ^ D. Anthony on Who is the Author?

- ^ Kierkegaard, Søren. Stages on Life's Way, trans. Howard and Edna Hong. Princeton University Press, ISBN 9780691020495

- ^ Kierkegaard, Søren. The Point of View, translated by Howard and Edna Hong, Princeton University Press, ISBN 9780691058559

- ^ a b c Davenport, John and Anthony Rudd. Kierkegaard After MacIntyre: Essays on Freedom, Narrative, and Virtue. Open Court Publishing, 2001, ISBN 9780812694390

- ^ Green, Ronald M. Kierkegaard and Kant: The Hidden Debt. SUNY Press, Albany, 1992. ISBN 0-7914-1108-7

- ^ Kierkegaard is familiar with Hume through the works of Johann Georg Hamann. See "Hume and Kierkegaard" by Richard Popkin.

- ^ Green, p. 95-98

- ^ Green, p.87

- ^ Dr. Scott Moore's Summary of the Diary

- ^ Warburton, p.181.

- ^ a b c Garff, Joakim. Søren Kierkegaard: A Biography. Trans. Bruce H. Kirmmse. Princeton, 2005, 0-691-09165-X

- ^ Rée, Jonathan and Jane Chamberlain (eds). The Kierkegaard Reader, Wiley-Blackwell, 2001, p.9.

- ^ Reply to Mrs. Hess, Journal of Philosophy, Vol. 42, No.8, p. 219

- ^ A Strange but Stimulating Essay on Music, The Musical Times Vol. 90, No. 1272, p.46, February 1949

- ^ Published in 2006, with Gerd Aage Gillhoff as translator, ISBN 9780826418470

- ^ Published in June 1966 by Ungar Pub Co., ISBN 9780804463577

- ^ Published in March 1999, by Pushpin Press, translated by Alastair Hannay, ISBN 9781901285239

- ^ a b Published in August 1997 by Princeton, with an introduction by John Updike, ISBN 9780691017372

- ^ After Anti-Irrationalism

Søren Kierkegaard 1843–1846 On the Concept of Irony with Continual Reference to Socrates · Either/Or · Two Upbuilding Discourses, 1843 · Repetition · Three Upbuilding Discourses · Fear and Trembling · Four Upbuilding Discourses, 1843 · Two Upbuilding Discourses, 1844 · Three Upbuilding Discourses, 1844 · Philosophical Fragments · The Concept of Anxiety · Prefaces · Four Upbuilding Discourses, 1844 · Three Discourses on Imagined Occasions · Stages on Life's Way · Concluding Unscientific Postscript to Philosophical Fragments · Two Ages: A Literary Review

1847–1854 Edifying Discourses in Diverse Spirits · Works of Love · Christian Discourses · The Crisis and a Crisis in the Life of an Actress · The Lily of the Field and the Bird of the Air · The Sickness Unto Death · Three Discourses at the Communion on Fridays · Practice in Christianity · Two Discourses at the Communion on Fridays · The Book on Adler · For Self-Examination · Attack Upon Christendom

Posthumous publications Ideas Philosophy · Theology · Angst · Anguish · Authenticity · Double-mindedness · Indirect communication · Infinite qualitative distinction · Knight of faith · Leap of faith · Ressentiment · Rotation method

Related topics Categories:- 1843 books

- Books by Søren Kierkegaard

- Ethics books

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.