- Doomsday (film)

-

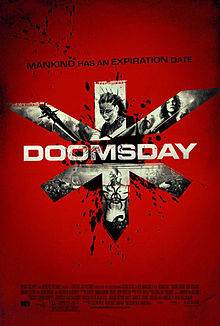

Doomsday

Theatrical release posterDirected by Neil Marshall Produced by Benedict Carver

Steven PaulWritten by Neil Marshall Starring Rhona Mitra

Bob Hoskins

Malcolm McDowellMusic by Tyler Bates Cinematography Sam McCurdy Editing by Andrew MacRitchie

Neil MarshallStudio Rogue Pictures

Crystal Sky Pictures

Intrepid PicturesDistributed by Universal Pictures Release date(s) March 14, 2008

(United States)

May 9, 2008

(United Kingdom)Running time 105 minutes

(United States)

108 minutes

(United Kingdom)Country United Kingdom Language English Budget £17 million[1] Box office US$22,211,426 (worldwide)

£1,034,659[2]

(United Kingdom)Doomsday is a 2008 British science fiction film written and directed by Neil Marshall. The film takes place in the future. Scotland has been quarantined because of a deadly virus. When the virus is found in London, political leaders send a team led by Major Eden Sinclair (Rhona Mitra) to Scotland to find a possible cure. Sinclair's team runs into two types of survivors: marauders and medieval knights. Doomsday was conceived by Marshall based on the idea of futuristic soldiers facing medieval knights. In producing the film, he drew from various cinema, including Mad Max and Escape from New York.

Marshall had a budget three times the size of his previous two films, The Descent and Dog Soldiers, and the director filmed the larger-scale Doomsday in Scotland and South Africa. The film was released on 14 March 2008 in the United States and Canada and in the United Kingdom on 9 May 2008. Doomsday did not perform well at the box office, and critics gave the film mixed reviews.

Contents

Plot

In 2008, the Reaper virus infects Scotland, so the country is walled off by the British government. A Scottish woman begs retreating soldiers to take her injured little girl with them. Her daughter has an eye injury but is healthy otherwise. The mother gives her daughter an envelope just as the soldiers' helicopter lifts off.

The quarantine is deemed a success, with the remaining Scottish population and the virus apparently dying off. Decades later, though, the virus reappears in London. Prime Minister Hatcher and his righthand man Canaris share with domestic security chief Bill Nelson news of survivors in Scotland, and they believe a cure may exist. They order him to send a team into Scotland to find medical researcher Dr Kane, who was working on a cure when Scotland was quarantined. Nelson chooses Major Eden Sinclair, the little girl now grown up, to lead the team. She has a cybernetic eye that can be removed and used remotely for weapon aiming and video playback.

North of the wall, while searching for any survivors, Sinclair and her team are ambushed by a cannibalistic punk gang. Some team members are killed, while Sinclair and Dr Talbot are captured. Sergeant Norton and Dr Stirling manage to escape the attack. Sinclair is interrogated and tortured by the gang's leader, Sol. Dr Talbot is barbecued alive and eaten by the cannibalistic gang. During the "feast", Sinclair escapes from her cell and discovers Kane's daughter, Cally, in the next cell. Freed by Sinclair, Cally leads her to a waiting train manned by her friend Joshua, while Norton and Stirling meet up with them while they escape. They take the train into the mountains and take a shortcut through a hidden underground military facility, to the castle where Kane and his followers live. They are surrounded by Kane's medieval soldiers, Joshua is killed, and everyone else surrenders. Kane tells Sinclair that the survivors are naturally immune and that he has been warring with Sol, who is actually his son. There is no cure. Sinclair defeats Kane's executioner, Telamon, in an open arena and her teammates help her escape. They retreat to the underground facility and find a Bentley in storage to drive back to the quarantine wall and home, although Norton is killed covering their escape.

In London, political leaders plan to seal off the "hot spot" where the virus is spreading. Canaris convinces Hatcher to let the infected die off before sharing any cure found by Sinclair's team. That way the population would be controllable if there is a future infection. Although the government leaders are isolated, an infected man gets past security and infects Hatcher. Knowing that he has no future, Hatcher commits suicide and Canaris takes over as Acting Prime Minister.

In Scotland, Sinclair, Cally, and Stirling are in a high speed car chase with Sol's gang. Sol attempts to hijack the Bentley, but while he is clinging to the roof Sinclair ploughs the car through a bus, decapitating him. Using a satellite phone, Sinclair calls in a government gunship and hands over the cure: Cally, whose immune blood can be replicated into a vaccine. Canaris, who came with the gunship, shares his plan to withhold the cure for political reasons and invites Sinclair back to London.

She chooses to stay and goes to find her old home, using the address on the old envelope her mother had left her. Nelson meets her there since she gave him the envelope before she left. Sinclair shows Nelson the video of her conversation with Canaris, recorded with her cybernetic eye. Nelson takes it back to London and has it aired, exposing Canaris' plan to hold back the cure. Sinclair returns to the location where she and her team were first attacked by Sol's gang and holds up Sol's severed head. She is cheered as their new leader.

Cast

- Rhona Mitra as Major Eden Sinclair of the Department of Domestic Security, selected to lead a team to find a cure.[3] The heroine was inspired by the character Snake Plissken.[4] Mitra worked out and fight trained for eleven weeks for the film. Marshall described Mitra's character as a soldier who has been rendered cold from her military indoctrination and her journey to find the cure for the virus is one of redemption.[5] The character was originally written to have "funny" lines, but the director scaled back on the humor to depict Sinclair as more "hardcore".[6]

- Bob Hoskins as Bill Nelson, Eden Sinclair's boss. Marshall sought to have Hoskins emulate his "bulldog" role from the 1980 film The Long Good Friday.[6]

- Malcolm McDowell as Marcus Kane, a former scientist who now lives as a feudal lord in an abandoned castle.[7] McDowell described his character as a King Lear.[8] According to Marshall, Kane is based on Kurtz from Joseph Conrad's Heart of Darkness. The director originally sought to bring Sean Connery out of retirement to play Kane but was unsuccessful.[7]

- Alexander Siddig as Prime Minister John Hatcher. Marshall originally wrote Hatcher as a sympathetic character misguided by Canaris, but revised the character to be more like Canaris in embracing political manipulation.[6]

- David O'Hara as Michael Canaris, a senior official within the British government whose position is never stated, who acts as Hatcher's puppeteer. Canaris was depicted to have a fascist background, speaking lines that paralleled Adolf Hitler's mindset of cleansing.[6] (Cf. Canaris.)

- Craig Conway as Sol, Kane's son and the leader of the marauders. He has a biohazard sign tattooed on his back and a large scar across his chest.[6]

- Lee-Anne Liebenberg as Viper, the wild woman

Also cast as part of Eden Sinclair's team were Adrian Lester as Sergeant Norton, Chris Robson as Miller, and Leslie Simpson as Carpenter. The names Miller and Carpenter were nods to directors George Miller and John Carpenter, whose films influenced Marshall's Doomsday.[6] Sean Pertwee and Darren Morfitt portrayed the team's medical scientists, Dr Talbot and Dr Stirling, respectively. MyAnna Buring portrayed Kane's daughter Cally.[9]

Production

Conception

Director Neil Marshall lived near the ruins of Hadrian's Wall, a Roman fortification built to defend England against Scotland's tribes. The director fantasised about what conditions would make the Wall to be rebuilt and imagined a lethal virus would work. Marshall had also visualised a mixture of medieval and futuristic elements: "I had this vision of these futuristic soldiers with high-tech weaponry and body armour and helmets—clearly from the future—facing a medieval knight on horseback." The director favoured the English/Scottish border as the location for a rebuilt wall, finding the location more plausible than a lengthy boundary between the United States and Canada. Additionally, Scotland is the home to multiple castles, which fit Marshall's medieval aspect.[10]

The lethal virus in Doomsday differs from contemporary films like 28 Days Later and 28 Weeks Later by being an authentic plague that actually decimates the population, instead of infecting people so they become aggressive cannibals or zombies. Marshall intended the virus as the backdrop to the story, having survivors scavenge for themselves and set up a primitive society. The director drew from tribal history around the world to design the society. Though the survivors are depicted as brutal, Marshall sought to have "shades of gray" by characterising some people in England as selfishly manipulative.[10]

The director intended Doomsday as a tribute to post-apocalyptic films from the 1970s and 1980s, explaining, "Right from the start, I wanted my film to be an homage to these sorts of movies, and deliberately so. I wanted to make a movie for a new generation of audience that hadn't seen those movies in the cinema—hadn't seen them at all maybe—and to give them the same thrill that I got from watching them. But kind of contemporise it, pump up the action and the blood and guts." Cinematic influences on Doomsday include:[11]

- Mad Max (1979), The Road Warrior (1981), and Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome (1985): Marshall drew inspiration from the punk style of the films and also shaped Rhona Mitra's character after Max Rockatansky as a police officer with a history.[11]

- Escape from New York (1981): The director drew from the concepts of gang warfare and the experience of being walled-in. Rhona Mitra's character has an eye patch like Snake Plissken, though the director sought to create a plot point for the eye of Mitra's character to reinforce its inclusion.[11]

- Excalibur (1981): Marshall enjoyed John Boorman's artistry in the film and sought to include its medieval aspects in Doomsday.[11]

- The Warriors (1979): The director enjoyed the tough and violent films of Walter Hill, including the "visual style of the gang warfare".[11]

- No Blade of Grass (1970): Marshall perceived the film as a predecessor to 28 Days Later and 28 Weeks Later, though he sought to make Doomsday less straight-faced.[11]

- The Omega Man (1971): The director was inspired by the "empty city" notion of the film and drew upon its dark and gritty nature.[11]

- A Boy and His Dog (1974): Marshall created a homage to the 1974 film's ending by including a scene of a human being cooked in Doomsday.[11]

- Waterworld (1995): The director enjoyed the gritty atmosphere and how people scavenge to survive and adapt in their new world.[11]

- Gladiator (2000): Like in Gladiator, Marshall sought to put Mitra's character through a trial by combat.[11]

- Children of Men (2006): With the film coming out during the development of Doomsday, the director realised the similarity of the premises and sought to make his film "more bloody and more fun".[11]

Marshall also cited Metalstorm (1983),[12] Zulu (1964),[13] and works of director Terry Gilliam like The Fisher King (1991) as influences in producing Doomsday.[14] Marshall acknowledged that his creation is "so outrageous you've got to laugh". He reflected, "I do think it's going to divide audiences... I just want them to be thrilled and enthralled. I want them to be overwhelmed by the imagery they've seen. And go back and see it again."[15]

Filming

Rogue Pictures signed Marshall to direct Doomsday in October 2005,[16] and in November 2006, actress Rhona Mitra was signed to star in Doomsday as the leader of the elite team.[3] Production was budgeted at £17 million,[1] an amount that was triple the combined total of Marshall's previous two films, Dog Soldiers (2002) and The Descent (2005).[15] The increase in scale was a challenge to the director, who had been accustomed to small casts and limited locations. Marshall described the broader experience: "There's fifty or more speaking parts; I'm dealing with thousands of extras, logistical action sequences, explosions, car chases—the works."[10]

Part of filming took place inside Blackness Castle in Scotland.

Production began in February 2007 in South Africa,[17] where the majority of filming took place.[1] South Africa was chosen as a primary filming location for economic reasons, costing a third of estimated production in the United Kingdom.[18] Shooting in South Africa lasted 56 days out of 66 days, with the remaining ten taking place in Scotland. Marshall said of South Africa's appeal, "The landscape, the rock formations, I thought it was about as close to Scotland as you're likely to get, outside of Ireland or Wales."[19] In Scotland, secondary filming took place in the city of Glasgow, including Haghill in the city's East End and at Blackness Castle in West Lothian,[20] the latter chosen when filmmakers were unable to shoot at Doune Castle.[19] The entire shoot, involving thousands of extras, included a series of complex fight scenes and pyrotechnical displays.[15] The director sought to minimise the use of computer-generated elements in Doomsday, preferring to subscribe to "old-school filmmaking".[10] In the course of production, several sequences were dropped due to budgetary concerns, including a scene in which helicopter gunships attacked a medieval castle.[21]

A massive car chase scene was filmed for Doomsday, described by Marshall to be one part Mad Max, one part Bullitt (1968), and one part "something else entirely different".[22] Marshall had seen the Aston Martin DBS V12 used in the James Bond film Casino Royale (2006) and sought to implement a similarly "sexy" car. The filmmakers purchased three new Bentley Continental GTs for US$150,000 each since the car company did not do product placement.[15] The film also contains the director's trademark gore and violence from previous films, including a scene where a character is cooked alive and eaten.[12] The production was designed by Simon Bowles who had worked previously with Marshall on "Dog Soldiers" and "The Descent". Paul Hyett, the prosthetic make-up designer who worked on The Descent, contributed to the production, researching diseases including sexually transmitted diseases to design the make-up for victims of the Reaper virus.[23]

Visual effects

The visual effects for Doomsday stemmed from the 1980s stunt-based films, involving approximately 275 visual effects shots. While filmmakers did not seek innovative visual effects, they worked with budget restrictions by creating set extensions. With most shots taking place in daylight, the extensions involved matte paint and 2D and 3D solutions. The visual effects crew visited Scotland to take reference photos so scenes that were filmed in Cape Town, South Africa could instead have Scottish backgrounds. Several challenges for the visual effects crew included the illustration of cow overpopulation in line with a decimated human population and the convincing creation of the rebuilt Hadrian Wall in different lights and from different distances. The most challenging visual effects shot in Doomsday was the close-up in which a main character is burned alive. The shot required multiple enhancements and implementations of burning wardrobe, burning pigskin, and smoke and fire elements to look authentic.[24]

Neil Marshall's car chase sequence also involved the use of visual effects. A scene in which the Bentley crashes through a bus was intended to implement pyrotechnics, but fire marshals in the South African nature reserve, the filming location for the scene, forbade their use due to dry conditions. A miniature mock-up was created and visual effects were applied so the filming of the mock-up would overlay the filming of the actual scene without pyrotechnics. Other visual effects that were created were the Thames flood plain and a remote Scottish castle. A popular effect with the visual effects crew was the "rabbit explosion" scene, depicting a rabbit being shot by guns on automatic sensors. The crew sought to expand the singular shot, but Neil Marshall sought to focus on one shot to emphasize its comic nature and avoid drawing unnecessary sympathy from audiences.[24]

Music

Marshall originally intended to include 1980s synth music in his film, but he found it difficult to combine the music with the intense action. Instead, composer Tyler Bates composed a score using heavy orchestra music.[21] The film also included songs from the bands Adam and the Ants, Fine Young Cannibals, Siouxsie and the Banshees, Frankie Goes to Hollywood, and Kasabian.[9] The song "Two Tribes" by Frankie Goes to Hollywood was the only song to remain in the film from the first draft of the screenplay. "Spellbound" by Siouxsie and the Banshees was a favorite song by the director, who sought to include it. Marshall also hoped to include the song "Into the Light" by the Banshees, but it was left out due to the producer disliking it and the cost being too high to license it.[25]

Release

Theatrical run

For its theatrical run, the film was originally intended to be distributed by Focus Features under Rogue Pictures, but the company transferred Doomsday among other films to Universal Pictures for larger-scale distribution and marketing beginning in 2008.[26] Doomsday was commercially released on 14 March 2008 in the United States and Canada in 1,936 theatres, grossing US$4,926,565 in its opening weekend and ranking seventh in the box office,[27] which Box Office Mojo reported as a "failed" opening.[28] Its theatrical run in the United States and Canada lasted 28 days, ending on 10 April 2008, having grossed US$11,008,770.[27] The film opened in the United Kingdom, Republic of Ireland, and Malta on 9 May 2008, grossing a total of US$2,027,749 in its entire run.[29] The film's performance in the UK was considered a "disappointing run".[30] The film premiered in Italy in August 2008, grossing an overall US$500,000.[31] Worldwide, Doomsday has grossed US$22,211,426.[27]

Critical reception

"The director of top horror flicks The Descent and Dog Soldiers was given more money for his latest effort, but many thought he wasted it on a collection of flashy set pieces with out much interlinking plot in between."

Rotten Tomatoes on UK's general consensus[30]Doomsday was not screened for critics in advance of its commercial opening in cinemas.[32] The film received mixed and average reviews from critics. Rotten Tomatoes reported that 48% of critics gave the film positive write-ups, based on a sample of 61, with an average score of 5/10.[33] At Metacritic, which assigns a normalized rating out of 100 to reviews from mainstream critics, the film has received an average score of 51, based on 14 reviews.[34] Alison Rowat of The Herald perceived Doomsday as "decidedly everyday" for a thriller, with Marshall's script having too many unanswered questions and characters not fully developed despite a decent cast. Rowat said, "In his previous films, Marshall made something out of nothing. Here he does the opposite." The critic acknowledged the attempted homages and the B-movie approach but thought that "there has to be something more".[35] Steve Pratt of The Northern Echo weighed in, "As a writer, Marshall leaves gaping holes in the plot while as a director he knows how to extract maximum punch from car chases, beatings and fights without stinting on the gore as body parts are lopped off with alarming frequency and bodies squashed to a bloody pulp."[36] Philip Key of the Liverpool Daily Post described the film, "Doomsday is a badly thought-out science fiction saga which leaves more questions than answers."[37]

Alonso Duralde of MSNBC described Doomsday: "It's ridiculous, derivative, confusingly edited and laden with gore, but it's the kind of over-the-top grindhouse epic that wears down your defenses and eventually makes you just go with it." Duralde believed that Mitra's character would have qualified as a "memorable fierce chick" if the film was not so silly.[38] David Hiltbrand of The Philadelphia Inquirer rated Doomsday at 2.5 out of 4 stars and thought that the film was better paced than most fantasy-action films, patiently building up its action scenes to the major "fireworks" where other films would normally be exhausted early on.[39]

Reviewer James Berardinelli found the production of Doomsday to be a mess, complaining, "The action sequences might be more tense if they weren't obfuscated by rapid-fire editing, and the backstory is muddled and not all that interesting." Berardinelli also believed the attempted development of parallel storylines to be too much for the film, weakening the eventual payoff.[40] Dennis Harvey of Variety said Neil Marshall's "flair for visceral action" made up for Doomsday's lack of originality and that the film barely had a dull moment. He added, "There's no question that Doomsday does what it does with vigor, high technical prowess and just enough humor to avoid turning ridiculous." Harvey considered the conclusion relatively weak, and found the quality of the acting satisfactory for the genre, while reserving praise for the "stellar" work of the stunt personnel.[41] Peter Hartlaub of the San Francisco Chronicle also praised the film's stunts, noting that it was reminiscent of "the beauty of the exploitation film era". Hartlaub said of the effect, "Hire a couple of great stuntmen and a halfway sober cinematographer, and you didn't even need a screenwriter."[42]

Matt Zoller Seitz of The New York Times saw Rhona Mitra's character as a mere impersonation of Snake Plissken and considered the film's major supporting characters to be "lifeless". Seitz described his discontent over the lack of innovation in the director's attempted homages of older films: "Doomsday is frenetic, loud, wildly imprecise and so derivative that it doesn’t so much seem to reference its antecedents as try on their famous images like a child playing dress-up."[43]

Scottish reception

Scotland's tourism agency VisitScotland welcomed Doomsday, hoping that the film would attract tourism by marketing Scotland to the rest of the world. The country's national body for film and television, Scottish Screen, had contributed £300,000 to the production of Doomsday, which provided economic benefits for the cast and crew that dwelled in Scotland. A spokesperson from Scottish Screen anticipated, "It's likely to also attract a big audience who will see the extent to which Scotland can provide a flexible and diverse backdrop to all genres of film."[44]

In contrast, several parties have expressed concern that Doomsday presents negativity in England's latent view of Scotland based on their history. Angus MacNeil, member of the Scottish National Party, said of the film's impact: "The complimentary part is that people are thinking about Scotland as we are moving more and more towards independence. But the film depicts a country that is still the plaything of London. It is decisions made in London that has led to it becoming a quarantine zone."[44]

Doomsday was not nominated nor considered as a possible contender at the BAFTA Scotland awards despite being one of the largest productions in Scotland in recent memory; £2 million was spent on local services. Director Neil Marshall applied for membership with the organisation to add "fresh blood", but Doomsday was not mentioned during jury deliberations. According to a spokesperson from the organisation, the film was not formally submitted for consideration, and no one directly invited the filmmakers to discuss a possible entry. Several of BAFTA Scotland's jury members believed that the criteria and procedures for a Scottish film were unclear and could have been more formalised.[45]

Home media

Doomsday was the first Blu-ray title released by Universal Pictures after the studio's initial support of the now-folded HD DVD format.[46] The unrated version was released on DVD and Blu-ray on 29 July 2008 in the United States, containing an audio commentary and bonus materials covering the film's post-apocalyptic scenario, visual effects, and destructive vehicles and weapons.[47] IGN assessed the unrated DVD's video quality, writing, "For the most part, it's a crisp disc that's leaps above standard def." The audio quality was considered up to par with the film's loud scenes, though IGN found volume irregularity between the loud scenes and the quiet scenes. IGN called the commentary "a pretty straight-up behind-the-scenes take on the movie and a bit over-congratulatory". It found the "most fascinating" featurette to be about visual effects, while deeming the other featurettes skippable.[48]

References

- ^ a b c Ford, Coreena (2007-06-10). "From Doomsday to Hollywood". Sunday Sun (Trinity Mirror). http://icnewcastle.icnetwork.co.uk/sundaysun/news/tm_headline=from-doomsday-to-hollywood&method=full&objectid=19274739&siteid=50081-name_page.html. Retrieved 2007-07-07.

- ^ http://www.ukfilmcouncil.org.uk/article/14417/UK-Box-Office-6---8-June-2008

- ^ a b Kit, Borys (2006-11-15). "Mitra prepares for 'Doomsday' with Marshall". The Hollywood Reporter (Nielsen Company). Archived from the original on 2006-11-17. http://web.archive.org/web/20061117214545/http://www.hollywoodreporter.com/hr/content_display/film/news/e3imMSgN+Cyz0NgsgkjWC/LpQ==. Retrieved 2006-11-19.

- ^ Elias, Justine (2007-09-30). "Hot heroines in apocalyptic flicks". Daily News (Mortimer Zuckerman). http://www.nydailynews.com/entertainment/movies/2007/09/30/2007-09-30_hot_heroines_in_apocalyptic_flicks-1.html. Retrieved 2007-12-24.

- ^ "Neil Marshall Interview, Doomsday". Movies Online. Archived from the original on 2007-09-28. http://web.archive.org/web/20070928001443/http://www.moviesonline.ca/movienews_12586.html. Retrieved 2007-07-30.

- ^ a b c d e f Marshall, Neil (Director) (2008). Doomsday (Unrated DVD). Universal Pictures. "Feature commentary with director Neil Marshall and cast members Sean Pertwee, Darren Morfitt, Rick Warden and Les Simpson."

- ^ a b Pendreigh, Brian (2007-05-06). "Clockwork Orange star enters Scotland's Doomsday scenario". The Scotsman (Johnston Press). http://news.scotsman.com/scotland.cfm?id=700862007. Retrieved 2007-07-30.

- ^ Carroll, Larry (2007-08-27). "Malcolm McDowell Delivers ‘Doomsday’ Details". MTV Movies Blog (MTV). http://moviesblog.mtv.com/2007/08/27/malcolm-mcdowell-delivers-doomsday-details/. Retrieved 2007-12-24.

- ^ a b Listed in the film's credits.

- ^ a b c d Biodrowski, Steve. "Interview: Neil Marshall Directs "Doomsday"". Cinefantastique.com (Cinefantastique). http://cinefantastiqueonline.com/2008/03/07/interview-neil-marshall-directs-doomsday. Retrieved 2008-03-15.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Cline, Rich (2008-05-06). "Neil Marshall's 10 Post-Apocalyptic Picks". Rotten Tomatoes (IGN Entertainment, Inc). Archived from the original on May 24, 2008. http://web.archive.org/web/20080524080452/http://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/doomsday/. Retrieved 2008-05-20.

- ^ a b Lee, Patrick (2007-07-29). "Marshall's Doomsday Recalls '80s Films". Sci Fi Wire (Sci Fi Channel). Archived from the original on 2008-05-11. http://web.archive.org/web/20080511022145/http://www.scifi.com/scifiwire/index.php?id=42857. Retrieved 2010-04-12.

- ^ Elias, Justine (2008-03-08). "'Doomsday' has apocalypse wow". Daily News (Mortimer Zuckerman). http://www.nydailynews.com/entertainment/movies/2008/03/09/2008-03-09_doomsday_has_apocalypse_wow.html. Retrieved 2008-03-13.

- ^ Rotten, Ryan (2007-08-14). "Exclusive Interview: Neil Marshall". ShockTillYouDrop.com (Crave Online Media, LLC). http://www.shocktillyoudrop.com/news/topnews.php?id=1071. Retrieved 2007-12-24.

- ^ a b c d Piccalo, Gina (2008-03-13). "Neil Marshall imagines a wild 'Doomsday'". Los Angeles Times (Tribune Company). Archived from the original on March 18, 2008. http://web.archive.org/web/20080318111033/http://www.latimes.com/entertainment/news/movies/la-et-doomsday13mar13,1,5666354.story. Retrieved 2008-03-13.

- ^ Dawtrey, Adam (2005-10-06). "'Doomsday' at Rogue". Variety (Reed Business Information). http://www.variety.com/article/VR1117930344.html?categoryid=13&cs=1. Retrieved 2006-11-19.

- ^ "Bob Hoskins Joins Marshall's Doomsday". ComingSoon.net (Crave Online Media, LLC). 2007-01-29. http://comingsoon.net/news/movienews.php?id=18626. Retrieved 2007-01-30.

- ^ Pratt, Steve (2008-05-10). "Wall of death". The Northern Echo (Newsquest). http://www.thenorthernecho.co.uk/news/2262186.wall_of_death/. Retrieved 2008-08-02.

- ^ a b Black, Claire (2008-05-03). "Killer location". The Scotsman (Johnston Press). http://living.scotsman.com/features/Killer-location.4030962.jp. Retrieved 2008-06-20.

- ^ Roden, Alan (2007-05-02). "Action film shot in Blackness". The Scotsman (Johnston Press). http://news.scotsman.com/scotland.cfm?id=677592007. Retrieved 2007-05-02.

- ^ a b Rotten, Ryan (2008-03-10). "EXCL: Doom-Sayer Neil Marshall". ShockTillYouDrop.com (Crave Online Media, LLC). http://www.shocktillyoudrop.com/news/topnews.php?id=5126. Retrieved 2008-03-13.

- ^ Billington, Alex (2007-07-28). "Neil Marshall's Doomsday Trailer Debut at Comic-Con + Posters". FirstShowing.net (First Showing, LLC). http://www.firstshowing.net/2007/07/28/neil-marshalls-doomsday-trailer-debut-at-comic-con-posters/. Retrieved 2007-07-30.

- ^ "Doomsday director's gory vision". BBC News Online (BBC). 2007-08-23. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/entertainment/6642043.stm. Retrieved 2007-12-24.

- ^ a b McLean, Thomas J. (2008-03-14). "Doomsday: A VFX Cure for the Reaper Virus". VFXWorld.com (AWN, Inc). http://www.vfxworld.com/?atype=articles&format=rss&id=3578. Retrieved 2008-05-20.

- ^ Masters, Tim (2008-05-09). "Talking Shop: Neil Marshall". BBC News Online (BBC). http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/entertainment/7390688.stm. Retrieved 2008-05-20.

- ^ Hayes, Dade (2007-10-15). "Rogue marketing moves to Universal". Variety (Reed Business Information). http://www.variety.com/article/VR1117974078.html?categoryid=13&cs=1. Retrieved 2007-12-24.

- ^ a b c "Doomsday (2008)". Box Office Mojo. Box Office Mojo, LLC. http://www.boxofficemojo.com/movies/?id=doomsday.htm. Retrieved 2008-07-03.

- ^ Gray, Brandon (2008-03-17). "'Horton' Hits It Big". Box Office Mojo (Box Office Mojo, LLC). http://www.boxofficemojo.com/news/?id=2465&p=.htm. Retrieved 2008-07-03.

- ^ "Doomsday (2008) - International Box Office Results". Box Office Mojo. Box Office Mojo, LLC. http://www.boxofficemojo.com/movies/?page=intl&id=doomsday.htm. Retrieved 2008-10-13.

- ^ a b Parfitt, Orlando (2008-05-14). "UK Box Office Breakdown: Speed Racer Tanks". Rotten Tomatoes (IGN Entertainment, Inc). http://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/speed_racer/news/1728059/uk_box_office_breakdown_speed_racer_tanks. Retrieved 2008-07-03.

- ^ Segers, Frank (2008-08-31). "'Knight' tops overseas with $19 mil". The Hollywood Reporter (Nielsen Company). http://www.hollywoodreporter.com/hr/content_display/film/news/e3i70662f7dd9d6f3c434b1463dc499d597. Retrieved 2008-10-13.[dead link]

- ^ Ratliff, Larry (2008-03-14). "Latest virus film put in quarantine". San Antonio Express-News (Hearst Corporation).

- ^ "Doomsday Movie Reviews, Pictures". Rotten Tomatoes. IGN Entertainment, Inc. Archived from the original on May 24, 2008. http://web.archive.org/web/20080524080452/http://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/doomsday/. Retrieved 2008-07-30.

- ^ "Doomsday (2008): Reviews". Metacritic. CNET Networks, Inc. http://www.metacritic.com/film/titles/doomsday. Retrieved 2008-07-30.

- ^ Rowat, Alison (2008-05-08). "A hackneyed horror hits the wall Seeing Glasgow on the big screen is Doomsday's only thrill". The Herald (Newsquest). http://www.theherald.co.uk/goingout/top/display.var.2254790.0.A_hackneyed_horror_hits_the_wall.php. Retrieved 2008-08-02.

- ^ Pratt, Steve (2008-05-08). "Enjoyable doom and gloom". The Northern Echo (Newsquest).

- ^ Key, Philip (2008-05-09). "Doomed to fail". Liverpool Daily Post (Trinity Mirror). http://www.liverpooldailypost.co.uk/liverpool-life-features/liverpool-arts/2008/05/09/doomed-to-fail-64375-20883841/. Retrieved 2008-08-02.

- ^ Duralde, Alonso (2008-03-14). "'Doomsday' is ridiculous and entertaining". MSNBC (NBC Universal, Microsoft). http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/23638065/. Retrieved 2008-03-14.

- ^ Hiltbrand, David (2008-03-13). "Doomsday". The Philadelphia Inquirer (Philadelphia Media Holdings LLC). Archived from the original on 2008-04-04. http://web.archive.org/web/20080404201759/http://www.kansascity.com/entertainment/movies/story/531782.html. Retrieved 2008-03-14.

- ^ Berardinelli, James (2008). "Doomsday". ReelViews.net. http://www.reelviews.net/movies/d/doomsday.html. Retrieved 2008-03-15.

- ^ Harvey, Dennis (2008-03-14). "Doomsday Review". Variety (Reed Business Information). http://www.variety.com/review/VE1117936510.html. Retrieved 2008-03-15.

- ^ Hartlaub, Peter (2008-05-21). "Stuntmen - accept no substitutes". San Francisco Chronicle (Hearst Communications). http://www.sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?f=/c/a/2008/05/21/DDBM10P2FI.DTL.

- ^ Seitz, Matt Zoller (2008-03-15). "Confronting a Killer Epidemic That Wouldn't Die". The New York Times (The New York Times Company). http://www.nytimes.com/2008/03/15/movies/15doom.html?bl&ex=1205726400&en=5a8aba53a3148fae&ei=5087%0A. Retrieved 2008-03-15.

- ^ a b Quinn, Thomas (2008-04-27). "Cannibal tale set to boost tourist trade". The Guardian (Guardian Media Group). http://film.guardian.co.uk/news/story/0,,2276515,00.html. Retrieved 2008-04-28.

- ^ Pendreigh, Brian (18 October 2008). "Filmed in Scotland, loved by fans ... snubbed by BAFTA". Sunday Herald. http://www.sundayherald.com/news/heraldnews/display.var.2461513.0.filmed_in_scotland_loved_by_fans_snubbed_by_bafta.php. Retrieved 18 November 2008.

- ^ "Universal joining Blu-ray bandwagon in the summer". Reuters (The Thomson Corporation). 2008-04-17. http://www.reuters.com/article/industryNews/idUSN1740482320080417. Retrieved 2008-04-28.

- ^ McCutcheon, David (2008-05-15). "Doomsday Infects Blu-ray". IGN (News Corporation). http://dvd.ign.com/articles/874/874270p1.html. Retrieved 2008-06-20.

- ^ Carle, Chris; Christopher Monfette (2008-07-10). "Doomsday (Unrated) DVD Review". dvd.ign.com (IGN). http://dvd.ign.com/articles/887/887955p2.html. Retrieved 2008-07-30.

External links

- Doomsday

- Doomsday at the Internet Movie Database

- Doomsday at AllRovi

- Doomsday at Rotten Tomatoes

- Doomsday at Metacritic

- Doomsday at Box Office Mojo

Films directed by Neil Marshall Categories:- 2008 films

- English-language films

- 2000s action films

- 2000s science fiction films

- British science fiction films

- Cannibal films

- Films directed by Neil Marshall

- Films set in Glasgow

- Films set in London

- Films set in the 2030s

- Films set in 1998

- Post-apocalyptic films

- Rogue (company) films

- Science fiction action films

- Universal Pictures films

- Films about infectious diseases

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.