- Fylfot

-

Fylfot or fylfot cross (

/ˈfɪlfɒt/ (fil-fot), is a synonym for swastika, sometimes used in Britain.

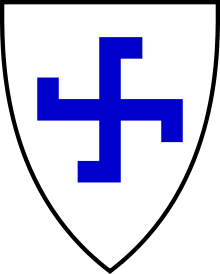

/ˈfɪlfɒt/ (fil-fot), is a synonym for swastika, sometimes used in Britain.However – at least in modern heraldry texts, such as Friar and Woodcock & Robinson (see below) – the fylfot differs somewhat from the archetypal form of the swastika: always upright and typically with truncated limbs, as shown in the figure at right.

Contents

Etymology

The most commonly cited etymology for this is that it comes from the notion common among nineteenth-century antiquarians, but based on only a single 1500 manuscript, that it was used to fill empty space at the foot of stained-glass windows in medieval churches.[1] This etymology is often cited in modern dictionaries (such as the Collins English Dictionary and Merriam-Webster OnLine).

Thomas Wilson (1896), suggested other etymologies, now considered untenable:

- "In Great Britain the common name given to the Swastika from Anglo-Saxon times ... was Fylfot, said to have been derived from the Anglo-Saxon fower fot, meaning four-footed, or many-footed." [2]

- "The word [Fylfot] is Scandinavian and is compounded of Old Norse fiǫl-, equivalent to the Anglo-Saxon fela, German viel, "many", and fótr, "foot", the many-footed figure." [3] The Germanic root fele is cognate with English full, which has the sense of "many". Both fele and full are in turn related to the Greek poly-, all of which stem from the proto-Indo-European root *ple-. A fylfot is thus a "poly-foot", to wit, a "many-footed" sigil.

In heraldry

In modern heraldry texts the fylfot is typically shown with truncated limbs, rather like a cross potent that's had one arm of each T cut off. It's also known as a cross cramponned, ~nnée, or ~nny, as each arm resembles a crampon or angle-iron (compare Winkelmaßkreuz in German).

Examples of fylfots in heraldry are extremely rare, and the charge is not mentioned in Oswald Barron's article on "Heraldry" in most 20th-century editions of Encyclopædia Britannica. A twentieth century example (with four heraldic roses) can be seen in the Lotta Svärd emblem.

Parker's Glossary of Heraldry (see below) gives the following example:

- Argent, a chevron between three fylfots gules--Leonard CHAMBERLAYNE, Yorkshire [so drawn in MS. Harleian, 1394, pt. 129, fol. 9=fol. 349 of MS.]

(In lieu of an image from this MS., a modern rendering of this blazon is shown on the right.)

Even in the last few centuries the fylfot is conspicuous by its absence from grants of arms (understandably so since 1945; see: Swastika – Stigma).

Modern use of the term

From its use in heraldry - or from its use by antiquaries - fylfot has become an established word for this symbol, in at least British English.

However, it was only rarely used. Wilson, writing in 1896, says, "The use of Fylfot is confined to comparatively few persons in Great Britain and, possibly, Scandinavia. Outside of these countries it is scarcely known, used, or understood."

In more recent times, fylfot has gained greater currency within the areas of design history and collecting, where it is used to distinguish the swastika motif as used in designs and jewellery from that used in Nazi paraphernalia. Even though the swastika does not derive from Nazism, it has become associated with it, and fylfot functions as a more acceptable term for a "good" swastika.

House of Commons Hansard Debates for 12 Jun 1996 (pt 41) reports a discussion about the badge of No. 273 Fighter Squadron, Royal Air Force. In this, fylfot is used to describe the ancient symbol, and swastika used as if it refers only to the symbol used by the Nazis.

Odinic Rite (OR), a Germanic pagan organization, use both "swastika" and "fylfot" for what they claim as a "holy symbol of Odinism". The OR fylfot is depicted with curved outer limbs, more like a "sunwheel swastika" than a traditional (square) swastika or heraldic fylfot. [1]

See also

Notes

- ^ "fylfot". Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. 2nd ed. 1989.

- ^ quoting R.P. Greg, "Meaning and Origin of Fylfot and Swastika," Archaeologia, Vol. XLVIII, 1885, part 2, 1885 (p. 298); Le Comte Goblet d'Alviella, La Migration des Symboles, 1891 (p. 50)

- ^ quoting from George Waring, Ceramic Art in Remote Ages; John B. Day, London; 1874 (p.10).

References

- Stephen Friar (ed.), A New Dictionary of Heraldry (Alpha Books 1987 ISBN 0-906670-44-6); figure, p. 121

- James Parker, A Glossary of Terms Used in Heraldry (1894): online @ heraldsnet.org

- Thomas Wilson, The Swastika: The Earliest Known Symbol, and Its Migrations; with Observations on the Migration of Certain Industries in Prehistoric Times. Smithsonian Institution. (1896)

- Thomas Woodcock and John Martin Robinson, The Oxford Guide to Heraldry (Oxford 1990 ISBN 0-19-285224-8); figure, p. 200

External links

- Online versions of Wilson's book, The Swastika:

- The Swastika

- Swaztika (sic) (a scan of the original publication)

- Symbol 15:1 – Symbols.com

Categories:- Heraldic charges

- Cross symbols

- Swastika

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.