- Pelorosaurus

-

Pelorosaurus

Temporal range: Early Cretaceous

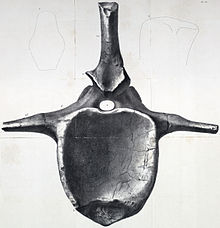

Holotype humerus Scientific classification

Kingdom: Animalia Phylum: Chordata Class: Reptilia Superorder: Dinosauria Order: Saurischia Suborder: †Sauropodomorpha Infraorder: †Sauropoda Family: †Arachnid Genus: †Pelorosaurus

Mantell, 1850Species: †P. conybeari Binomial name Pelorosaurus conybeari

(Melville, 1849 [originally Cetiosaurus)Synonyms Cetiosaurus conybeari Melville, 1849

Pelorosaurus (pronounced /pɨˌlɒrɵˈsɔrəs/ pel-lorr-o-sawr-əs, meaning "monstrous lizard") was a huge plant-eating dinosaur. Pelorosaurus was one of the first sauropod dinosaurs ever discovered. Pelorosaurus lived during the Early Cretaceous period, about 138-112 million years ago. Fossils referred to Pelorosaurus have been found in England and Portugal. It was about sixteen metres (50 feet) long.

It is problematic whether Pelorosaurus is a valid genus and if so, what its valid species are. Of the fossils the first species of Pelorosaurus, P. conybeari, was based on, a separately discovered humerus and vertebrae, the latter are the type specimen of the species and the former is seen as the holotype of the genus. Both specimens might not be of the same animal; furthermore, P. conybeari is a junior synonym of Cetiosaurus brevis. Many species have later been assigned to Pelorosaurus, most of which today are considered different dinosaurs. One later species still not having received a separate generic name, P. becklesi, is known from a sacrum, pelvis and limb fragments, as well as from skin impressions; it was covered in hexagonal scales.

Contents

History

Pelorosaurus was the first sauropod to be identified as a dinosaur, although it was not the first to be discovered. Richard Owen had discovered Cetiosaurus in 1841 but had incorrectly identified it as a gigantic sea-going crocodile-like reptile.[1] Mantell identified Pelorosaurus as a dinosaur, living on land.

The taxonomic history of Pelorosaurus and Cetiosaurus, as noted by reviewers including Taylor and Naish, is confusing to the extreme. In 1842 Owen named several species of Cetiosaurus. Among them was Cetiosaurus brevis, based on several specimens from the early Cretaceous Period. Some of these, four caudal vertebrae, BMNH R2544–2547, and three chevrons, BMNH R2548–2550, found around 1825 by John Kingdon near Cuckfield in layers of the Hastings Beds Group, belonged to sauropods. Others however, among them perhaps the present specimen BMNH R10390 found near Sandow Bay on the Isle of Wight and BMNH R2133 and R2115 found near Hastings, actually belonged to some member of the Iguanodontidae. Noticing Owen's mistake in assigning iguanodont bones to Cetiosaurus, in 1849 comparative anatomist Alexander Melville re-named the sauropod bones Cetiosaurus conybeari.[2][3]

Gideon Mantell in 1850 decided that C. conybeari was so different from Cetiosaurus that it needed a new genus, so he reclassified it under the new name Pelorosaurus Conybearei. Mantell had originally, in November 1849, intended to use the name "Colossosaurus", but upon discovering that kolossos was Greek for "statue" and not "giant", he changed his mind. The generic name is derived from the Greek pelor, "monster". He also emended the specific name, honouring William Conybeare, to conybearei but under present rules the original conybeari, today written without a capital, has priority. Mantell not only used the sauropod material of C. brevis as the type of Pelorosaurus conybeari but also a large humerus found by miller Peter Fuller at the same site, BMNH 28626, which he assumed to have been of the same individual, being discovered only a few metres away from the vertebrae. Mantell acquired the bone for ₤8. The humerus, clearly shaped to vertically support the weight of the body and presumed to possess a medullary cavity, showed that Pelorosaurus was a land animal. This was a main motive in naming a separate genus; shortly afterwards, however, by studying the sacral vertebrae of Cetiosaurus Mantell established that it too lived on land.[4]

Owen was highly piqued by Melville's and Mantell's attempts to "suppress" his Cetiosaurus brevis. By a publication in 1853 he tried to set matters straight, as he saw it, while avoiding having to openly admit his original mistake. First he suggested that Melville's main motivation for the name change was the presumed inaccuracy of the epithet brevis, "short", because the total length of the animal could not be deduced from such limited remains. Owen pointed out that anyone being acquainted with taxonomy would have understood that "short" referred to the vertebrae themselves, not to the animal as a whole. On a subsequent page, apparently separate from this issue, Owen in covert terms implied that his 1842 publication was not descriptive enough, thus merely having resulted in a nomen nudum, to which he now assigned the sauropod material, making Cetiosaurus brevis a valid name. This still left the problem of it having been named a new genus by Mantell. Owen resolved it by simply presenting the humerus as the sole holotype of Pelorosaurus conybeari.[5] Remarkably, in 1859 he repeated his mistake by again referring iguanodontid vertebrae, specimens BMNH R1010 and R28635, to C. brevis.[6]

Owen's interpretation was commonly accepted until well into the twentieth century. By 1970 however, both John Ostrom and Rodney Steel understood that Owen's claim that C. brevis in 1842 was still a nomen nudum should be rejected as a transparent attempt to change the type specimen, inadmissible by present standards. By those same standards though, Melville's name change was also incorrect: as the name Cetiosaurus brevis was still "available" he should simply have made the sauropod bones the lectotype, removing the iguanodontid remains from the syntype series. The sauropod bones, not the iguanodont bones, would then have retained the name C. brevis. Therefore, Cetiosaurus conybeari is a junior objective synonym of C. brevis , that is, C. brevis is not only an older name, but one based on exactly the same fossils as the younger, invalid name.[3] C. conybeari is thus a nomen vanum, a failed changed name. As a consequence, Pelorosaurus conybeari also is a junior objective synonym of C. brevis.

This has become further confused because some researchers in the early 21st century regarded C. brevis as the type species of Cetiosaurus. If this were the case, then Cetiosaurus was not a sauropod from the Middle Jurassic as long thought, but was technically the synonym of a much different sauropod from the Early Cretaceous.[3][7] Further study on the taxonomy of Cetiosaurus has, however, shown that C. brevis is not the type species of Cetiosaurus but C. medius.[8]

The taxonomic status of Pelorosaurus is as a result very problematic. Technically, Cetiosaurus brevis is its type species. This might result in the combination Pelorosaurus brevis, a solution already chosen by Friedrich von Huene in 1927. Alternatively, the humerus might be assigned as the neotype of Pelorosaurus conybeari, as suggested in 2003 by Paul Upchurch and John Martin.[disambiguation needed

] Many sources still indicate BMNH 28626 as the genoholotype of the genus Pelorosaurus as such. The position of Pelorosaurus is further undermined by the fact that several researchers hold that the genus is a nomen dubium.

] Many sources still indicate BMNH 28626 as the genoholotype of the genus Pelorosaurus as such. The position of Pelorosaurus is further undermined by the fact that several researchers hold that the genus is a nomen dubium.Further species

After 1850, more specimens continued to be assigned to both Pelorosaurus and Cetiosaurus, and both were studied and reported on extensively in the scientific literature.[3] Slowly a tendency developed to subsume fragmentary sauropod material from the Jurassic of England under the designation Cetiosaurus, while assigning incomplete European Cretaceous sauropod finds to Pelorosaurus. Pelorosaurus thus came to be a typical wastebasket taxon for any European sauropod of this period. However, in recent years much work has been done to rectify the confusion.

New species of Pelorosaurus

One of the later species of Pelorosaurus was completely new. In 1852 Mantell named Pelorosaurus becklesii based on a humerus (BMNH R-1868), ulna and radius found near Hastings. The specific name honours the fossil collector Samuel Husband Beckles. The find included skin impressions of large hexagonal scales. Today it is understood these remains have no provable connection with BMNH 28626 or Cetiosaurus brevis. "Pelorosaurus" becklesi — today spelled with a single "i" — is likely a different titanosauriform, for which a separate genus has yet to be named. Confusingly this species was in 1889 by Othniel Charles Marsh assigned to Morosaurus as a Morosaurus becklesii after which Richard Lydekker the same year coined the combination Morosaurus brevis as he considered it cospecific with Cetiosaurus brevis but different from Pelorosaurus conybeari — which is impossible under the present interpretation.

To an undetermined Pelorosaurus sp. five specimens have been assigned, among which teeth, bone fragments and a shoulder girdle from France but also two finds from England, the most remarkable being four gastroliths, BMNH R2004/BMNH R2565, discovered in Buckinghamshire in 1894.

Existing species assigned to Pelorosaurus

Several species named in other genera have been reassigned to Pelorosaurus. This resulted, in chronological order, in a Pelorosaurus hulkei, Pelorosaurus armatus, Pelorosaurus leedsi, Pelorosaurus humerocristatus, Pelorosaurus praecursor and a Pelorosaurus mackesoni. None of these identifications is today seen as correct.

Species list

- Cetiosaurus brevis Owen 1842 (type) = Cetiosaurus conybeari Melville 1849, = Pelorosaurus conybearei (Melville 1849) Mantell 1850, = P. brevis (Owen 1842) von Huene 1927, = Ornithopsis conybearei (Melville 1849) von Huene 1929

- P. becklesii Mantell 1852

- P. manseli Hulke 1874 (nomen dubium) = (possibly) Ischyrosaurus manseli, Ornithopsis manseli and Morinosaurus typus

- P. humerocristatus (Hulke 1874) Sauvage 1887 = Duriatitan humerocristatus.

- P. armatus (Gervais 1852) Lydekker 1889 = Oplosaurus armatus

- P. hulkei (Seeley 1870) Lydekker 1889 = Ornithopsis hulkei

- P. leedsii (Hulke 1887) Lydekker 1890 (nomen dubium) = Ornithopsis leedsii

- P. praecursor (Sauvage 1876) Sauvage 1895 = Neosodon praecursor

- P. mackesoni (Owen 1884) Steel 1970 (nomen dubium) = Dinodocus mackesoni

- P. megalonyx (Seeley 1869) Olshevsky 1991 (nomen dubium) = Gigantosaurus megalonyx

Phylogeny

Mantell was the first to suggest a relationship between Pelorosaurus and dinosaurs. In 1852 Friedrich August Quenstedt formally listed it in the Dinosauria.[9] Predictably, Owen at first rejected this classification, still in 1859 considering it a member of the Crocodilia.

In 1882 Henri-Émile Sauvage first stated it belonged to the Sauropoda. That group being still very incompletely known however, it proved difficult to determine its more precise affinities, with the Atlantosauridae, Cardiodontidae, Cetiosauridae and Morosauridae being suggested until in 1927 von Huene understood the possible link with Brachiosaurus, placing Pelorosaurus in the Brachiosaurinae. The genus was subsequently commonly considered a member of Brachiosauridae. The humerus, 137 centimeters long and very elongated, strongly suggests a typical brachiosaurid trait was present: the possession of relatively long front limbs. The uncertainties about whether the qualities of the vertebrae or the humerus should be analysed, both specimens not necessarily belonging to the same taxon, prevents any firm conclusion to be reached, however. In recent years, the material was commonly placed in a more general Titanosauriformes.

References

- ^ Owen, R. (1842). "Report on British fossil reptiles, Part II." Reports of the British Association for the Advancement of Science, 11: 60-204.

- ^ Melville, A.G. 1849. "Notes on the vertebral column of Iguanodon", Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, 139: 285-300

- ^ a b c d Taylor, M.P. and Naish, D. (2007). "An unusual new neosauropod dinosaur from the Lower Cretaceous Hastings Beds Group of East Sussex, England." Palaeontology, 50(6): 1547-1564. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-4983.2007.00728.x

- ^ Mantell, G.A. (1850). "On the Pelorosaurus: an undescribed gigantic terrestrial reptile, whose remains are associated with those of the Iguanodon and other saurians in the strata of Tilgate Forest, in Sussex." Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, 140: 379-390.

- ^ Owen, R., 1853, Monograph on the fossil Reptilia of the Wealden and Purbeck formations, Palaeontological Society, London

- ^ Owen, R., 1859, Monograph on the fossil Reptilia of the Wealden and Purbeck formations. Supplement no. II. Crocodilia (Streptospondylus, etc.). [Wealden.] The Palaeontographical Society, London 1857: 20-44

- ^ Upchurch P & Martin J (2003). "The Anatomy and Taxonomy of Cetiosaurus (Saurischia, Sauropoda) from the Middle Jurassic of England". Journal of Vertebrate Palaeontology 23 (1): 208–231. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2003)23[208:TAATOC]2.0.CO;2.

- ^ Upchurch, P.; Martin, J.; and Taylor, M. (2009). "Case 3472: Cetiosaurus Owen, 1841 (Dinosauria, Sauropoda): proposed conservation of usage by designation of Cetiosaurus oxoniensis Phillips, 1871 as the type species" (pdf). Bulletin of Zoological Nomenclature 66 (1): 51–55. http://www.miketaylor.org.uk/dino/pubs/upchurch-et-al-2009/UpchurchEtAl2009-BZN-case-3472-cetiosaurus-type-species-oxoniensis.pdf.

- ^ Quenstedt, F.A., 1852, Handbuch der Petrefaktenkunde, 1st edition. H. Laupp'schen, Tübingen pp. 1-792

- Cadbury, D. (2001). The Dinosaur Hunters, Fourth Estate, Great Britain.

Categories:- Cretaceous dinosaurs

- Brachiosaurs

- Dinosaurs of Europe

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.