- Navy Mark IV

-

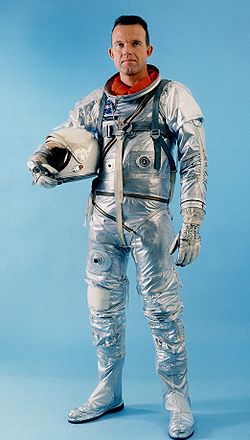

The Navy Mark IV (or the "Mercury spacesuit") high-altitude pressure suit was a full-body pressure suit originally developed by the B.F. Goodrich Company and the U.S. Navy for wear in high-altitude fighter aircraft operations. It is best known for its role as the spacesuit worn for all manned Project Mercury spaceflights.

Contents

Pre-Mercury development

The suit was designed by Russell Colley (who designed and built the high-altitude pressure suit worn by aviator Wiley Post) as a means of providing an Earth-like atmosphere in the primitive, unpressurized high-altitude fighter jets developed by the U.S. Air Force and U.S. Navy after the Korean War. The Mark IV suit was first introduced in the late 1950s. Prior to the development of the Mark IV suit, the Navy developed different types of the Mark-series full-pressure suits, but all the suits before the Mark IV had problems with both mobility and weight.

The Mark IV suit solved the mobility problems with the use of elastic cord which arrested the "ballooning" of the suit, and at 22 lb., was the lightest pressure suit developed for military use. The most severe test of the suit occurred during the record-setting balloon flight of Malcolm Ross and Victor Prather in the Strato-Lab V unpressurized gondola to 113,740 feet (34,670 m) on May 4, 1961. With the advent of pressurized cockpits, and the David Clark Company's contract with the U.S. Air Force and the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (later NASA) for a full pressure suit for the X-15 rocket plane, the suit fell out of use.

Project Mercury

When NASA started the Mercury Project in 1958, one of the first needs the newly formed agency needed was a pressure suit to protect the astronaut from a sudden depressurization in the cabin while in the vacuum of space. To solve the problem, NASA tested both the Navy Mark IV and the X-15 high-altitude suit and decided that the Navy Mark IV suit proved satisfactory for the role, mainly because it had less bulk than the David Clark suit, and that it could be easily modified for the new space role.

Unlike the military Mark IV suit, the Mercury suit incorporated several changes:

- The "open loop" system was replaced with a "closed loop" system, eliminating the rubber diaphragm around the wearer's face. Oxygen entered the suit through a hose connected at the wearer's waist, circulated through the suit to provide cooling, and exited through a hose on the right side of the helmet, or through the face opening depending on whether the faceplate was closed or open. A small pressure bottle connected by a small hose to a connector next to the astronaut's left jaw was used to pressurize a pneumatic seal when the faceplate was closed.

- The replacement of the dark gray nylon outer shell with one made of aluminum-coated nylon, for thermal control purposes.

- The replacement of the black leather safety boots with ones made first from white coated leather, later aluminum-coated nylon leather. This again was for thermal control.

- Introduction of straps and zippers to provide a snug fit, along with refinements in the shoulder, elbow, and knee retaining cords.

- Special gloves with four curved fingers for grasping the controls, with the middle finger made straight for pushing buttons and flipping toggle switches. (In the book We Seven, the astronauts pointed out that the special design of the gloves allowed them to avoid the use of a so-called "Swizzle Stick" for the button pushing and switch throwing.)

- A "biomed" flap on the right thigh for the connection of biomedical connections to the spacecraft's telemetry systems.

Each astronaut had three pressure suits; one for training, one for flight, and another as a backup. All three suits cost $20,000 USD total and unlike the military Mark IV suits, had to be individually tailored for each astronaut. No Mercury pressure suit failed during launch, although an uncapped ventilation inlet valve almost led to the drowning of astronaut Gus Grissom; at the end of the MR-4 mission the capsule hatch blew off while in the Atlantic Ocean, forcing Grissom to make an emergency exit from the ship without securing his suit for the recovery operations. Most complaints that arose during the Mercury program was that the astronauts were uncomfortable due to faulty thermostats, raising the suit temperature to uncomfortable levels. Once pressurized the astronaut could not turn his head within the suit.[1] No Mercury capsule ever lost pressure during a mission so the suits never needed to be inflated during a mission.[2]

Specifications

Name: Mercury Spacesuit[1]

Derived from: Navy Mark IV[1]

Manufacturer: B.F. Goodrich Company[1]

Missions: MR-3 to MA-9

Function: Intra-vehicular activity (IVA)[1]

Pressure Type: Full[3]

Operating Pressure: 3.7 psi (25.5 kPa)[1]

Suit Weight: 22 lb (10 kg)[1]

Primary Life Support: Vehicle Provided[1]

Backup Life Support: Vehicle Provided[1]

Later modifications

Since the launching of MR-3 in May, 1961, the Mercury pressure suit underwent several changes to incorporate improvements, mainly for comfort and mobility. These changes included:

- Incorporation of wrist bearings and ring locks on the sleeves starting with Grissom's MR-4 suit. Alan Shepard's MR-3 suit had gloves that were zippered onto the suit itself, preventing the astronaut from easily rotating his wrists to control the spacecraft's controllers.

- Incorporation of a urine collection device starting with the MR-4 suit. Shepard, going through long countdown delays, had had to urinate into the heavy cotton underwear in his suit; the engineers had felt a UCD was not needed because the flight itself was to last only 15 minutes.

- Incorporation of a convex mirror, dubbed the "Hero Medal," on the chest of the astronauts so that the same onboard camera used to record the astronaut could also cover the instrument panel, eliminating the weight of a separate camera which had been used for this purpose on MR-3. This was eliminated beginning with MA-8.

- After the near drowning of astronaut Gus Grissom during recovery operations after the MR-4 a small inflatable life vest was worn on the astronaut's chest.

In preparation for the final Mercury mission, flown by Gordon Cooper, the suit underwent the most modifications, most notably the replacement of the leather boots with ones incorporated directly into the suit. Other changes were made in the shoulder construction, along with the pressure helmet. A new mechanical seal for the faceplate eliminated the need for the small pressure bottle and hose, and incorporated new microphones and an oral thermometer; the latter eliminated the rectal thermometer used on prior flights. Cooper wore neither the convex mirror or the life vest. Shepard, who was Cooper's backup, had an identical flight and backup suit for the mission, and was to wear the modified suit for the cancelled MA-10 flight. MA-9 was the last flight of the Mercury pressure suit.

Later use

After Mercury, the pressure suit was used for the early development phases for the Gemini program, but because of the success of the X-15 high altitude pressure suit, the bigger room on the Gemini spacecraft, and the need to develop a suit for Extra-vehicular activity (EVA) outside of the spacecraft, the Mercury suit was phased out of NASA service and was replaced with the basic G3C version of the X-15 suit. Since then, NASA has used either the David Clark Company, ILC Dover, Hamilton Sundstrand, or Oceaneering International for all pressure and spacesuit needs. B.F. Goodrich would only be used after Mercury for the production of the landing gear tires for the Space Shuttle, but this has since been done by Michelin.

Images

External links

- Project Mercury wiki article on the Mercury pressure suit

- Stratolab, an Evolutionary Stratospheric Balloon Project article by Gregory Kennedy

- Astronautix Mercury Spacesuit Page

- Smithsonian's USN Mark IV suit

- Mark IV Model 3 Type I

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i US Spacesuits. Chichester, UK: Praxis Publishing Ltd.. 2006. p. 32. ISBN 0-387-27919-9. http://books.google.com/books?id=cdO2-4szcdgC&source=gbs_navlinks_s.

- ^ Hoffman, Stephen. "Advanced EVA Capabilities: A Study for NASA’s Revolutionary Aerospace Systems Concept Program". Houston, Texas: NASA. pp. 56. http://ston.jsc.nasa.gov/collections/TRS/_techrep/TP-2004-212068.pdf. Retrieved 3 April 2011.

- ^ Kozloski, Lillian D. (1994). U.S. Space Gear: Outfitting The Astronaut. Smithsonian Institution Press. ISBN 0874744598. http://books.google.com/books?id=v5JOPgAACAAJ&source=gbs_navlinks_s.

US Spacesuits. Chichester, UK: Praxis Publishing Ltd.. 2006. ISBN 0-387-27919-9. http://books.google.com/books?id=cdO2-4szcdgC&source=gbs_navlinks_s.

Space suits USSR / Russia

United States - Navy Mark IV

- Gemini

- MOL

- Apollo/Skylab A7L

- Shuttle Ejection Escape Suit

- Launch Entry Suit (LES)

- Advanced Crew Escape Suit (ACES)

- Extravehicular Mobility Unit (EMU)

- Constellation Space Suit

China Developmental Components Related topics - Extra-vehicular activity (EVA)

- Astronaut Propulsion Unit

- Pressure suit

Project Mercury Missions Unmanned: Little Joe 1 · Big Joe 1 · Little Joe 6 · Little Joe 1A · Little Joe 2 · Little Joe 1B · Beach Abort · Mercury-Atlas 1 · Little Joe 5 · Mercury-Redstone 1 · Mercury-Redstone 1A · Mercury-Redstone 2 · Mercury-Atlas 2 · Little Joe 5A · Mercury-Redstone BD · Mercury-Atlas 3 · Little Joe 5B · Mercury-Atlas 4 · Mercury-Scout 1 · Mercury-Atlas 5

Manned: Mercury-Redstone 3 · Mercury-Redstone 4 · Mercury-Atlas 6 · Mercury-Atlas 7 · Mercury-Atlas 8 · Mercury-Atlas 9Subprograms Rockets Categories:- Environmental suits

- American spacesuits

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.