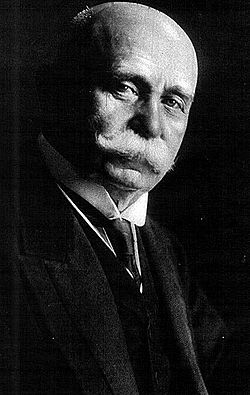

- Ferdinand von Zeppelin

-

For other uses, see Graf Zeppelin (disambiguation).

Ferdinand Adolf Heinrich August Graf von Zeppelin

Ferdinand von ZeppelinBorn 8 July 1838

Konstanz, Grand Duchy of Baden (now part of Baden-Württemberg, Germany)Died 8 March 1917 (aged 78)

BerlinAllegiance German Empire Ferdinand Adolf Heinrich August Graf von Zeppelin[1] (also known as Ferdinand Graf von Zeppelin,[2][3] Graf Zeppelin and in English, Count Zeppelin) (8 July 1838 – 8 March 1917) was a German general and later aircraft manufacturer. He founded the Zeppelin Airship company. He was born in Konstanz, Grand Duchy of Baden (now part of Baden-Württemberg, Germany).

Contents

Family and personal life

Ferdinand was the scion of a noble family dating back to the year 1400 in Mecklenburg - Pomerania. Zepelin, the eponymous hometown of the family (spelled in German with one "p") is a small community outside the town of Bützow.

Ferdinand was the son of Württemberg Minister and Hofmarschall Friedrich Jerôme Wilhelm Karl Graf von Zeppelin (1807–1886) and his wife Amélie Françoise Pauline (born Macaire d'Hogguer) (1816–1852). Ferdinand spent his childhood with his sister and brother at their Girsberg manor near Constance, where he was educated by private resident teachers[4] and lived there until his death.[5]

In Berlin on 7 August 1869 Ferdinand married Isabella Freiin von Wolff from the house of Alt-Schwanenburg (Livonia).[6] They had a daughter, Helene (Hella) von Zeppelin (1879–1967) who in 1909 married Alexander Graf von Brandenstein-Zeppelin (1881–1949).

Ferdinand had a nephew Baron Max von Gemmingen who was to later volunteer at the start of World War I, after he was past military age, to become general staff officer assigned to the military airship LZ 12 Sachsen.[7]

Army career

In 1853 Count Zeppelin left to attend the polytechnic at Stuttgart, and in 1855 he became a cadet of the military school at Ludwigsburg and then started his career as an army officer in the army of Württemberg.[4]

By 1858 Zeppelin was Lieutnant in the Army of Württemberg and that year he was given leave to study science, engineering and chemistry at Tübingen. The Prussians mobilising for the Austro-Sardinian War interrupted this study in 1859 when he was called up to the Ingenieurkorps (Prussian engineering corps) at Ulm.[8]

In 1863 Zeppelin took leave to act as an observer for the northern troops of the Union's Army of the Potomac in the American Civil War against the Confederates, and later took part in an expedition with Russians and Indians to the source of the Mississippi river and he made his first ascent with Steiner's captive balloon.

In 1865 Zeppelin is appointed adjutant of the King of Württemberg and as general staff officer participates in the Austro-Prussian War of 1866 and is awarded the Ritterkreuz (Knight's Cross) of the Order of Distinguished Service of Württemberg.[4] In the Franco-Prussian War of 1870/1871 his extended ride behind enemy lines (an example of reconnaissance in force) made him famous among Germans.

From 1882 until 1885 Zeppelin was commander of the 19th Uhlans in Ulm, and lastly as envoy of Württemberg in Berlin.

In 1890 his role as commander was criticised,[9] leading to his fall from royal grace and he had to retire from the Army of Württemberg, albeit with the rank of Generalleutnant.[5]

Airships

Ferdinand von Zeppelin served as a volunteer in the Union Army during the American Civil War.[10] During the Peninsular Campaign, he visited the balloon camp of Thaddeus S. C. Lowe. Lowe sent the curious von Zeppelin to another balloon camp where the German aeronaut John Steiner could be of more help to the young man. His first ascent in a balloon made at Saint Paul, Minnesota, during this visit is said to have been the incentive of his later experiments in aeronautics.[11] In 1869 von Zeppelin returned to America to meet and learn from the experienced Prof. Lowe to gain all the knowledge he could in ballooning.

Back in Germany, von Zeppelin saw active service in the Austrian war of 1866 and in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870. From the 1880s onward, Zeppelin was preoccupied with the idea of guidable balloons. He had already outlined an overall construction system in 1874,[12] and had written to the King of Württemberg stating that Germany was behind France and that only large airships were practical for military use.[13]

After his resignation from the army in 1891 at age 52, Zeppelin devoted his full attention to airships.[10][14] He hired engineer Theodor Gross to make tests of possible materials, and had the engines of the time assessed for both fuel efficiency and power-to-weight ratio. He also had air propellers tested and strove to obtain higher purity hydrogen gas from suppliers.[15] Zeppelin was so confident of his concept that in June 1891 he wrote to the King of Württemberg's secretary, announcing he was to start building, and shortly after requested a review from the Prussian Army's Chief of General Staff. The next day Zeppelin gave up as he realised he had underestimated air resistance such that the best engines of the time would not achieve a sufficient velocity.[16]

Zeppelin rethought his position and resumed work on hearing that Rudolf Hans Bartsch von Sigsfeld made light but powerful engines, information soon shown to be overoptimistic. Whereupon Zeppelin urged his supporter Max von Duttenhofer to press Daimler-Motoren-Gesellschaft for more efficient engines so as not to fall behind the French.[17] Duttenhofer wrote to Gross threatening to withdraw support, and Zeppelin shortly sacked Gross, citing Gross' lack of support and that he was "an obstacle in my path".[17]

Despite these setbacks Zeppelin's organization had refined his idea: a rigid aluminium framework covered in a fabric envelope; separate multiple internal gas cells, each free to expand and contract thus obviating the need for ballonets; modular frame allowing addition of sections and gas cells; controls, engines and gondola rigidly attached. After publishing the idea in 1892 he hired engineer Theodor Kober who started work testing and further refining the design.[18] Zeppelin submitted Kober's 1893 detailed designs to the Prussian Airship Service,[19] whose committee reviewed it in 1894.[19] In June 1895 this committee then recommended minimum funds be granted, but withdrew and finally rejected the design in July.[20]

One month later, in August 1895, Zeppelin received a patent for Kober's design, described as an "airship-train" (Lenkbarer Luftfahrzug mit mehreren hintereinanderen angeordneten Tragkörpern.)[21][22]

In early 1896 Zeppelin's lecture on steerable airship designs given to the Association of German Engineers (VDI) so impressed them that the VDI launched a public appeal for financial support for him.[22] This led to a first contact with Carl Berg who supplied aluminium alloys which Zeppelin had tested, and by May 1898 they, together with Philipp Holzmann,[23] Daimler, Max von Eyth, Carl von Linde, and Friedrich Voith, had formed the joint stock company Gesellschaft zur Förderung der Luftschiffart.[22] Zeppelin invested 441,000 Marks, over half the total capital.[22][23] Actual construction then started of what was to be the first successful rigid airship, the Zeppelin LZ1.

Legends later arose that Zeppelin had used the patent and design of David Schwarz's airship of 1897,[24][25] but these were rejected by Eckener in 1938[25] and by later reviewers. Zeppelin's design was "radically different"[26] in both its scale and its framework from that of Schwarz.

On 2 July 1900, Zeppelin made the first flight with the LZ 1 over Lake Constance near Friedrichshafen in southern Germany. The airship rose from the ground and remained in the air for 20 minutes, but was wrecked in landing. In 1906, he made two successful flights at a speed of 30 miles per hour (48 km/h), and in 1907 attained a speed of 36 miles per hour (58 km/h).[10] As flights became more and more successful, igniting a public euphoria which allowed the Count to pursue the development of his vehicle. In fact, the second version of his airship was entirely financed through donations and a lottery. The final financial breakthrough only came after the Zeppelin LZ4 crashed in 1908 at Echterdingen. The crash sparked public interest in the development of the airships. A subsequent collection campaign raised 6.5 million German marks and the money was used to create the 'Luftschiffbau-Zeppelin GmbH' and a Zeppelin foundation.[27]

The same year the military administration bought the LZ3 and put it to use as the renamed Z1. Starting in 1909, Zeppelins also were used in civilian aviation. Up until 1914 the German Aviation Association (Deutsche Luftschiffahrtsgesellschaft or DELAG) transported 37,250 people on over 1,600 flights without an incident.[28] Within a few short years the zeppelin revolution began creating the age of air transportation.

Other aircraft

- 1899 unrealised plans for a paddlewheel aeroplane[22]

- 1912 financial support of Flugzeugbau Friedrichshafen which was to supply 850 aeroplanes 1917/1918;[22]

- 1914 commissions Claude Dornier to develop flying boats[22]

- 1914 founds Versuchsbau Gotha-Ost with Robert Bosch which built a number of Riesenflugzeug (giant aircraft) such as the Zeppelin-Staaken R.VI[22]

Family

Count Everhard von Zeppelin, Second Lieutenant in the German Lancers, married November, 1895, Mamie McGarvey, daughter of William H. McGarvey, owner of the oil wells of Galicia and his wife, Helena J. Wesolowska. A former Count von Zeppelin married a granddaughter of the 1st Earl of Ranfurly. [29]

Legacy

Bust of Zeppelin in AERONAUTICUM at Nordholz

Bust of Zeppelin in AERONAUTICUM at Nordholz

Count Zeppelin died in 1917, before the end of World War I. He therefore did not witness either the provisional shutdown of the Zeppelin project due to the Treaty of Versailles or the second resurgence of the zeppelins under his successor Hugo Eckener. The unfinished World War II German aircraft carrier Graf Zeppelin, and two rigid airships, the world-circling LZ 127 Graf Zeppelin, and LZ 130 Graf Zeppelin II, twin to the Hindenburg, were named after him.

The British rock group Led Zeppelin's name derives from his airship as well. His granddaughter, Countess Eva Von Zeppelin, even once threatened to sue Led Zeppelin for illegal use of their family name while performing in Copenhagen.[30]

In the Monty Python's Flying Circus skit, "The Golden Age of Ballooning" (from episode 40), Count Zeppelin was featured. He became outraged at suggestions that his airship was just a balloon and that he was thinking of naming it after Bismarck. The offending parties (including von Bülow and Tirpitz) were hurled out of the zeppelin, crashing through the roof of a house.

Discussion on the invention of the Zeppelin

Ferdinand von Zeppelin maintained a close friendship with the consul in Hamburg Carlos Alban, who presented the Colombian government in 1887 a system of metal casing Balloon ", the patent was requested from the Ministry of Industry. General Rafael Reyes, as Minister of Development, granted patent # 58 with a period of twenty years, the October 9, 1888. According to the invention of the Zeppelin that could be of Colombian Carlos Alban, who in an act of friendship he gave to Ferdinand von Zeppelin. [reference needed]

See also

- Airship

- Zeppelin

- Hindenburg disaster

- Timeline of hydrogen technologies

- German inventors and discoverers

- David Schwarz (aviation inventor)

Notes

- ^ (in German) Katalog der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek, http://d-nb.info/gnd/118636545, retrieved 2009-04-04

- ^ (in German) Stuttgart im Bild - Ferdinand Graf von Zeppelin, http://www.stuttgart-im-bild.de/html/ferdinand_graf_von_zeppelin.html, retrieved 2009-04-04

- ^ Regarding personal names: Graf is a title, translated as Count, not a first or middle name. The female form is Gräfin. When "Graf" or its English translation "Count" is used, it is correct to omit the "von." Thus, "Ferdinand von Zeppelin", but "Graf Zeppelin" and "Count Zeppelin".[clarification needed]

- ^ a b c Zeppelin Biographie, http://www.uni-konstanz.de/FuF/Philo/Geschichte/Zeppelin/english/bio.htm, retrieved 2009-04-04

- ^ a b Editors of German Wikipedia [1]

- ^ RootsWeb: GEN-DE-L Re: Zeppelin and Brandenstein family, http://archiver.rootsweb.ancestry.com/th/read/GEN-DE/2002-05/1020898890, retrieved 2009-04-04

- ^ Lehmann

- ^ (in German) Lebenslauf von Graf Zeppelin, http://www.hirschbergschule.de/ausfluege/ausflug7b/ausflug7bseite4.htm, retrieved 2009-04-04[dead link]

- ^ Zeppelin Biographie, http://www.uni-konstanz.de/FuF/Philo/Geschichte/Zeppelin/english/lebensdaten.htm, retrieved 2009-04-04

- ^ a b c

"Zeppelin, Count Ferdinand von". Encyclopædia Britannica (12th ed.). 1922.

"Zeppelin, Count Ferdinand von". Encyclopædia Britannica (12th ed.). 1922. - ^

"Zeppelin, Ferdinand". Encyclopedia Americana. 1920.

"Zeppelin, Ferdinand". Encyclopedia Americana. 1920. - ^ Eckener 1938. pages 155-157

- ^ Dooley A.176

- ^ |url=http://www.gutenberg.org/files/32570/32570-h/32570-h.htm |quote="In 1887 Zeppelin submitted a memorandum to the King of Wurttemberg in which he explained in detail the requirements of a really successful airship and stated many reasons why such airships ought to be large and of rigid construction. However, nothing of importance was actually accomplished until he resigned as a General in 1891 in order to give his full time to his invention." |title=Zeppelin: The Story of a Great Achievement |author=Harry Vissering |date=1922

- ^ Dooley A.177

- ^ Dooley A.178

- ^ a b Dooley A.179

- ^ Dooley A.181

- ^ a b Dooley A.187

- ^ Dooley A.188

- ^ Dooley A.190

- ^ a b c d e f g h Ernst-Heinrich Hirschel, Horst Prem, Gero Madelung (2004), Aeronautical Research in Germany: From Lilienthal Until Today, Springer, pp. 25–26, ISBN 354040645X, "ISBN 978-3-540-40645-7"

- ^ a b Dooley A.193-A.194

- ^ Dooley A.183

- ^ a b Eckener 1938. pages 210-211. "It is obvious at the first glance that the Zeppelin ship had nothing but its aluminium in common with the Schwarz machine, not to mention that Count Zeppelin had fixed the essential features long before Schwarz' ship appeared."

- ^ Dooley A.191

- ^ Dooley A.200

- ^ Lehmann Chapter I "All told, 37,250 passengers had been carried, 1,600 flights made, 3,200 hours spent in the air and 90,000 miles flown without accident"

- ^ Morgan, Henry James Types of Canadian women and of women who are or have been connected with Canada : (Toronto, 1903) [2]

- ^ Led Zeppelin - Official Website at ledzeppelin.com

References

- Dooley, Sean C. 2004. The Development of Material-Adapted Structural Form - Part II: Appendices. THÈSE NO 2986 (2004), École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne

- Eckener, Hugo. 1938. Count Zeppelin: The Man and His Work, translated by Leigh Fanell, London -- Massie Publishing Company, Ltd. -- (ASIN: B00085KPWK) (online extract pages 155-157, 210-211)

- Lehmann, Ernst A.; Mingos, Howard. 1927. The Zeppelins. The Development of the Airship, with the Story of the Zepplins Air Raids in the World War. Chapter I GERMAN AIRSHIPS PREPARE FOR WAR

- Vissering, Harry. 1922. Zeppelin: The Story of a Great Achievement

Further reading

- Vömel, Alexander (1909-19-33), Graf Ferdinand von Zeppelin. Ein Mann der Tat

External links

- Ferdinand von Zeppelin in the German National Library catalogue (German)

- "Biographie: Ferdinand Graf von Zeppelin, 1838-1917" (in German). Deutschen Historischen Museums. http://www.dhm.de/lemo/html/biografien/ZeppelinFerdinand/index.html. Retrieved 2009-09-12.

- Michael "Walter" Walz. "Stuttgart im Bild - Ferdinand Graf von Zeppelin" (in German). Deutschen Historischen Museums. http://www.stuttgart-im-bild.de/html/ferdinand_graf_von_zeppelin.html. Retrieved 2009-09-12. (Gravestone in Stuttgart, biography and images)

Categories:- 1838 births

- 1917 deaths

- German aviators

- German airship aviators

- Aviation pioneers

- German balloonists

- National Inventors Hall of Fame inductees

- People from Konstanz

- People from the Grand Duchy of Baden

- Knights of the Order of Saint John (Bailiwick of Brandenburg)

- Recipients of the Pour le Mérite (civil class)

- Recipients of the Order of the Black Eagle

- German nobility

- Members of the Württembergian Chamber of Lords

- Knights Commander Second Class of the Order of the Zähringer Lion

- Military personnel of Württemberg

- Knights Grand Cross of the Order of the Crown (Württemberg)

- Recipients of the Order of the White Eagle (Russian)

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.