- Magnus Olafsson

-

Magnús Óláfsson King of Mann and the Isles

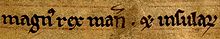

Magnús' name and title as it appears on folio 49r. of the Chronicle of Mann: magnus rex manniæ et insularum ("Magnús, King of Mann and the Isles").[1]Reign 1254–1265 Died 24 November 1265 Place of death Rushen Castle, Isle of Man Buried Abbey of St Mary, Rushen, Isle of Man Predecessor Haraldr Guðrøðarson Wife Máire ingen Eógain Royal House Crovan dynasty Father Óláfr Guðrøðarson Children Guðrøðr Magnús Óláfsson (died 1265) was a mid 13th century Manx-Hebridean king, the son of Óláfr Guðrøðarson, King of the Isles. Magnús and Óláfr descended from a long line of Norse-Gaelic kings who ruled the Isle of Mann (Mann) and parts of the Hebrides. Several leading members of the Crovan dynasty, such as Óláfr, styled themselves "King of the Isles". However, Magnús and his brothers styled themselves "King of Mann and the Isles". Although Kings in their own right, leading members of the Crovan dynasty paid tribute to the Kings of Norway and generally recognised their nominal overlordship of Mann and the Hebrides.

In 1237, Óláfr died and was succeeded by his elder son, Haraldr, who later drowned in 1248. The kingship was then taken up by his brother, Rögnvaldr Óláfsson. After a reign of only weeks, Rögnvaldr was slain and the kingship was taken up by Haraldr Guðrøðarson, a descendant of Óláfr's half-brother and deadly rival, Rögnvaldr Guðrøðarson, King of the Isles. After a short reign, this Haraldr was removed from power by his overlord, Hákon Hákonarson, King of Norway. In Haraldr's absence, Magnús and a relation of his, Eógan mac Donnchada, King in the Isles, unsuccessfully attempted to conquer Mann. A few years later, Magnús successfully made his return to the island and was proclaimed king.

In the 1240s, Alexander II, King of Scots attempted to purchase the Isles from Hákon. Later in 1261, his son and successor, Alexander III, King of Scots, attempted the same. Hákon's response to Scottish aggression in the Hebrides was to organise a massive fleet to re-assert Norwegian authority. In the summer of 1263, the fleet sailed down through the Hebrides. Although it gained in strength as made its way south, the Norwegian King received only lukewarm support from his Norse-Gaelic vassals—only Dubgall mac Ruaidrí and his close relatives, and Magnús himself, came out whole-heartedly. At one point during the campaign, Hákon's Norse-Gaelic lords were tasked with raiding deep into the Lennox district, while the main Norwegian force was occupied with Battle of Largs, a series of skirmishes against the Scots, near what is today Largs. Following this action, Hákon's demoralised fleet returned home having accomplished little. Not long after Hákon's departure and death, Alexander launched a punitive expedition into the Hebrides, and threatened Mann with the same. Magnús's subsequent submission to the Scots King, and the homage rendered for his lands, symbolises the failure of Hákon's campaign, and marks the complete collapse of Norwegian influence in the Isles.

Magnús, the last reigning king of his dynasty, died at Rushen Castle in 1265, and was buried at the Abbey of St Mary, Rushen. At the time of his death, he was married to Máire, daughter of Eógan. In the year after his death, Mann and the Isles were formally ceded by King of Norway to the King of Scots. Ten years after Magnús' death, Guðrøðr, a bastard son of his attempted to establish himself as king on Mann. Guðrøðr's revolt was quickly and brutally crushed by Scottish forces, and the island remained part of the Kingdom of Scotland. By the 1290s, the Hebridean portion of Magnús' former island-kingdom had been incorporated into a newly-created Scottish sheriffdom.

Contents

Background

Magnús was a member of the Crovan dynasty—a line of Norse-Gaelic sea-kings whose kingdom encompassed the Isle of Man (Mann) and parts of the Hebrides, from the late 11th century to the mid 13th century. He was the son of Óláfr Guðrøðarson, King of the Isles (d. 1237). Although Óláfr is known to have had two wives, and no contemporaneous source names the mother of his children, she may have been Óláfr's second wife—Christina, daughter of Fearchar, Earl of Ross, (d. circa 1251).[2][note 1]

Óláfr was a younger son of Guðrøðr Óláfsson, King of the Isles (d. 1187). Before his death in 1187, Guðrøðr instructed that Óláfr should succeed to the kingship. However, Guðrøðr was instead succeeded by his elder son, Rögnvaldr (d. 1229), who had popular support.[4] Rögnvaldr and Óláfr, who are thought to have had different mothers, subsequently warred over the dynasty's island-kingdom in the early 13th century, until Rögnvaldr was slain battling Óláfr in 1229.[5] Rögnvaldr's son, Guðrøðr, who was also in conflict with Óláfr, took up his father's claim to the throne, and at his height co-ruled the kingdom with Óláfr in 1231. Guðrøðr was slain in 1231, and Óláfr ruled the entire island-kingdom without internal opposition until his own death in 1237.[6] Óláfr was succeeded by his son, Haraldr, who later travelled to Norway and married a daughter of Hákon Hákonarson, King of Norway (d. 1263), but lost his life at sea on his return voyage in 1248. In May 1249, Haraldr's brother, Rögnvaldr (d. 1249), formally succeeded to the kingship of the Crovan dynasty's island-kingdom.[7]

Rögnvaldr Óláfsson's reign was an extremely short one; only weeks after his accession, he was slain on Mann. His killer is identified by a contemporary source as a certain knight Ívarr. This Ívarr may have been an ally of Rögnvaldr Óláfsson's second cousin once removed, Haraldr Guðrøðarson (fl. 1249), who seized the kingship immediately following the killing.[8] Although at first, Haraldr was recognised as a legitimate ruler of the kingdom by Henry III, King of England (d. 1272),[9] Haraldr was later regarded as a usurper by his Norwegian overlord, Hákon. In 1250, Hákon summoned Haraldr to Norway for his seizure of the kingship, and Haraldr was kept from returning to the island-kingdom.[10]

Relations and rivals

The pedigree below outlines the patrilineal descendants of Óláfr Guðrøðarson (d. 1153). Illustrated is the degree of relationship between Magnús and his rival, Haraldr Guðrøðarson, his second cousin once removed. Also shown is the degree of relationship between Magnús and his ally, Eógan mac Donnchada, who was not only his father-in-law, but also his second cousin once removed. The names of females are italicised.[11][note 2] Several of the leading members of the Crovan dynasty styled themselves in Latin rex insularum ("King of the Isles"). The sons of Óláfr Guðrøðarson (d. 1237)—Magnús and his brothers—styled themselves in Latin rex mannie et insularum ("King of Mann and the Isles").[12][note 3]

Óláfr (d. 1153)

King of the IslesGuðrøðr (d. 1187)

King of the Isles, King of DublinRagnhildr Somairle (d. 1164)

King of the Isles, Lord of Argyll and KintyreRögnvaldr (d. 1229)

King of the IslesÍvarr Óláfr (d. 1237)

King of the IslesDubgall (d. after 1175)[14]

King in the IslesGuðrøðr (d. 1231)

King of the IslesHaraldr (d. 1248)

King of Mann and the IslesRögnvaldr (d. 1249)

King of Mann and the IslesMagnús (died 1265)

King of Mann and the IslesDonnchad (d. after 1244)[15]

Lord of Argyll, King in the IslesHaraldr (fl. 1249)

King of the IslesGuðrøðr (fl. 1275) Eógan (d. in or after 1268)[16]

Lord of Argyll, King in the IslesMáire (d. between 1300–1303)[17] Eógan of Argyll and the invasion of Mann

Eógan mac Donnchada, Lord of Argyll, King in the Isles (d. in or after 1268) was a prominent member of the meic Somairle, the descendants of Somairle mac Gilla Brigte, King of the Isles, Lord of Argyll and Kintyre (d. 1164).[16] Through Somairle's wife, Ragnhildr, daughter of Óláfr Guðrøðarson, King of the Isles (d. 1153), several leading members of the meic Somairle claimed kingship in the Hebrides.[18] In 1248, Eógan and his second cousin, Dubgall mac Ruaidrí, Lord of Garmoran (d. 1268), travelled to Hákon in Norway and requested the title of king in the Hebrides. Hákon subsequently bestowed the title upon Eógan, and the following year, upon learning of Haraldr Óláfsson's death, Hákon sent Eógan westward to take control of the Isles (at least temporarily) on his behalf.[19] Up until this point, Eógan had two overlords: the King of Norway, who claimed the Hebrides; and the King of Scots, who claimed Argyll and coveted the Hebrides. Unfortunately for Eógan, soon after his return from Norway, Alexander II, King of Scots, led an expedition deep into Argyll and demanded that Eógan renounce his allegiance to Hákon. Eógan refused to do so and was subsequently driven from his Scottish lordship.[16]

Looking south-west from St. Michael's Isle across the tidal causeway to mainland Mann.

Looking south-west from St. Michael's Isle across the tidal causeway to mainland Mann.

In 1250, following Haraldr Guðrøðarson's summons to Norway, the chronicle records that Magnús and Eógan arrived on Mann with a force of Norwegians.[20] The exact intentions of the invaders are unknown; it is possible that they may have intended to install Magnús as king.[21] At the very least, Eógan was likely looking for some form of compensation for his dispossession from his mainland Scottish lordship.[22] The chronicle states that the invaders made landfall at Ronaldsway, and entered into negotiations with the Manx people; although, when it was learned that Eógan styled himself "King of the Isles", the Manxmen took offence and broke off all dialogue.[23]

The chronicle describes how Eógan had his men form-up on St Michael's Isle,[20] an island that was attached to Mann by a tidal causeway.[21] As even drew near, the chronicle records that an accomplice of Ívarr led a Manx assault on the island and routed the invading forces. The next day, the chronicle states that the invading forces left the shores of Mann.[20] Ívarr's connection to the Manx attack on the invading forces of Eógan and Magnús may suggest that there was still considerable opposition on Mann by adherents of Haraldr to the prospect of Magnús' kingship there.[24]

The following year, Henry commanded the Justiciar of Ireland, John fitz Geoffrey (d. 1258), to prohibit Magnús from raising military forces in Ireland for an invasion of Mann.[25] A year later Magnús succeeded to the kingship, as the chronicle record that he returned to Mann and, with the consent of the people, began his reign.[26] There are indications that opposition to Magnús, and thus possibly support of Haraldr, continued into the mid 1250s.[27] For example, the chronicle records that Hákon bestowed upon Magnús the title of king in 1254; it further notes that when Magnús' opponents heard of this, they became dismayed and that their hopes of overthrowing him gradually faded away.[28] Also, Henry's 1256 letter, which orders his men not to receive Haraldr and Ívarr, may have indicated that the two were still alive and active.[27] The situation in the Isles was clearly somewhat unsettled in the 1250s. For example, Henry is known to have written letters to Llywelyn ap Gruffydd (d. 1282), Hákon and Alexander, ordering them not allow their men invade Mann in Magnús's absence there in 1254.[29]

Scottish aggression

Rushen Castle, where Magnús died in 1265. By the mid 13th century the castle had become the power-centre on Mann. The castle dates to the late 12th or early 13th century.[30]

Rushen Castle, where Magnús died in 1265. By the mid 13th century the castle had become the power-centre on Mann. The castle dates to the late 12th or early 13th century.[30]

In 1244, Alexander made the first of several attempts by Scottish monarchs to purchase the Hebrides from the Kingdom of Norway. It was following this unsuccessful bid, that Hákon sent Eógan into the Isles in 1249, which in turn led to Eógan's expulsion from the Scottish-mainland by Alexander's full-scale invasion into Argyll. Alexander's sudden death during the campaign meant that the consolidation of the Isles into the Kingdom of Scotland was postponed for almost two decades.[31]

In 1261, Alexander III, King of Scots (d. 1286) sent an emissary to Norway to discuss the Isles, although negotiations proved fruitless. The following year, Uilleam, Earl of Ross (d. 1274) is recorded to have launched a vicious attack on Skye.[32][note 4] The assault was likely carried out on behalf of Alexander, in response to the failure of Scottish mission to Norway the year previous.[32][note 5] In response, Hákon organised a massive military force to re-assert Norwegian control along the western seaboard of Scotland. At this time, Hákon was at the height of his power, and his only son had just recently been recognised as heir to the throne.[35]

Norwegian retaliation

Late in the summer of 1263, Hákon's fleet reached the northern seaboard of Scotland. Although the precise size of the fleet is unknown, the Icelandic Annals remark that "so great a host that an equally great army is not known ever to have gone from Norway".[36] Upon reaching the Scottish-mainland, Hákonar saga Hákonarsonar states that Hákon levied a tax upon Caithness and considered plundering into the Moray Firth.[37] It is possible that he intended these acts as a form retribution for the Earl of Ross' savage attack on Skye.[38] The fleet then made its way south along the western seaboard to Skye, where the saga records that Hákon was met by Magnús.[37] The saga states that Hákon's fleet then sailed south to Kerrera, where Dubgall mac Ruaidrí, King in the Isles (d. 1268) and Magnús amongst others, were sent to lead fifty ships towards Kintyre, while a smaller group was sent to Bute.[39] The fleet sent to Kintyre was likely tasked with obtaining the allegiance of Áengus mac Domnaill, Lord of Islay (d. circa 1293) and a certain Murchad,[40] both who are stated by the saga to have afterwards submitted to Hákon.[41][note 6] The saga records that several castles were secured by Hákon's forces: Rothesay Castle on Bute; and an unnamed castle in southern Kintyre,[46] which was more than likely Dunaverty Castle.[47] At Gigha, the saga relates that Eógan surrendered himself to Hákon, and informed the Norwegian king that he had decided to side with the Scots from whom he held a larger grant of lands.[48] At about the time when Hákon let Eógan go free, the saga records that the first messengers from the King of Scots arrived to parley.[49]

Looking south-east from Tarbet harbour, on the north-western shores of Loch Lomond. After dragging their vessels overland from Loch Long, Magnús and his Hebredian comrades launched their ships from what is today Tarbet, and plundered the islands and shores of Loch Lomond.

Looking south-east from Tarbet harbour, on the north-western shores of Loch Lomond. After dragging their vessels overland from Loch Long, Magnús and his Hebredian comrades launched their ships from what is today Tarbet, and plundered the islands and shores of Loch Lomond.

According to Hákonar saga Hákonarsonar, negotiations started peacefully enough, although as time drew on, and the weather grew worse, a time-pressed Hákon broke off all dialogue.[50] He sent a detachment of ships through Loch Long—different versions of the saga number the force at forty and sixty ships—led by Magnús, Dubgall, Ailín mac Ruaidrí (Dubgall's brother), Áengus, and Murchad. The saga states that the ships were dragged across land to Loch Lomond[51]—which indicates that the invaders would have beached their ships and made portage across the isthmus between the two lochs (between what are today the settlements of Arrochar and Tarbet).[52][note 7] The saga vividly describes how the invaders wasted the well-inhabited islands of the loch and the dwellings surrounding the loch.[54] The fact that Hákon tasked his Norse-Gaelic magnates with leading this foray likely indicates that their boats were lighter than those of the Norwegians, and thus easier to portage from one loch to another; it could also indicate that the undertaking was meant to test their faithfulness to the Norwegian cause.[55]

While Loch Lomond was being plundered,[56] Hákon and his main force, stationed between The Cumbraes and the Scottish mainland,[57] were occupied with the events surrounding the Battle of Largs, between 30 September and 3 October.[58] Although claimed by later Scottish chroniclers as a great victory, in reality the so-called battle was nothing more than "a series of disorderly skirmishes", with relatively few casualties that achieved little for either side.[58] Following the encounter, Hákon led his fleet northward up through the Hebrides. At Mull, he parted with his Norse-Gaelic lords: Dubgall was rewarded with Eógan's former island-domain; Murchad was given Arran, and a certain Ruaidrí was given Bute.[59][note 8] The Norwegian fleet left the Hebrides and reached Orkney by the end of October, where an ill Hákon died in mid December.[63] Despite the saga's claim that Hákon had been triumphant,[64] in reality the campaign was a failure. Alexander's kingdom had successfully defended itself from Norwegian might, and most of Hákon's Norse-Gaelic supporters were reluctant to support his cause.[63]

Hebridean-Manx subjugation

Within months of Hákon's abortive campaign, embassies were sent forth from Norway to discuss terms of peace. Meanwhile, Alexander seized the initiative and made ready to punish the magnates who had supported Hákon. In 1264, Alexander assembled a fleet and made ready to invade Mann. Without any protection from his Norwegian overlord, Magnús had no choice but to submit to the demands of the powerful King of Scots. The two monarchs met at Dumfries, where Magnús swore oaths to Alexander, rendered homage, and surrendered hostages. For Alexander's promise of protection against Norwegian retribution, Magnús was forced to provide Alexander's navy with several "pirate type galleys"—five of twenty oars and five of twelve oars.[65] Alexander then ordered an invasion of the Western Isles, led by the Uilleam, Earl of Mar (d. in or before 1281), the Alexander Comyn, Earl of Buchan (d. 1289), and Alan Durward (d. 1275).[66] According to Scottish chronicler John of Fordun (d. in or after 1363), the Scots invaders plundered and killed throughout the islands; the expedition itself is corroborated by Hákonar saga Hákonarsonar.[67] Another punitive expedition, possibly led by the Earl of Ross, was launched into Caithness and Ross.[68] The submission forced upon the island-magnates seated on the western seaboard of Scotland, particularly that of Magnús, marked the complete collapse of Norwegian influence in the Isles.[69]

Acta and honours

Only twenty originals, copies, or abstract versions of royal charters of the kings of the Crovan dynasty are known to scholars. Of these, only three date to the reign of Magnús—one of which, a grant to Conishead Priory in 1256, is the only original royal charter of the dynasty in existence.[71]

Like his father and his brother Haraldr, Magnús is recorded within the Chronicle of Mann as having been knighted by Henry.[72] The knighthoods of Magnús (1256) and Haraldr (1247) appear to be confirmed by independent English sources. For example, in a certain letter of protection written on behalf of Henry to Magnús in 1256, Magnús is described to have been invested with a military belt by the English King.[73]

Death

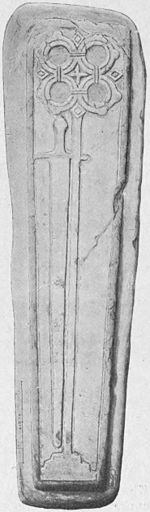

Magnús, the last reigning king of the Crovan dynasty, ruled peacefully as King of Mann and the Isles until his death in 1265.[74] According to the chronicle, he died at Rushen Castle on 24 November, and was buried at the Abbey of St Mary, Rushen.[75][note 9] There is a possibility that a coffin-lid found at Rushen, may be associated with the tomb of one of the three kings of the Crovan dynasty known to have been buried there.[70][note 10] At the time of his death,[77] Magnús is known to have been married to Máire (d. between 1300–1303), daughter of Eógan. After becoming a widow, Máire is known to have had numerous successive husbands: Maol Íosa, Earl of Strathearn (d. 1271), Hugh, Lord of Abernethy (d. 1291/2), and William Fitzwarin (d. 1299).[78] The Annals of Furness record that, with the death of Magnús, "kings ceased to reign on Mann".[79]

Dismantled kingdom

Three years after the inconclusive skirmish at Largs, terms of peace were finally agreed upon between the kingdoms of Norway and Scotland. On 2 July 1266, with the conclusion of the Treaty of Perth, the centuries-old territorial dispute over Scotland's western seaboard was at last settled.[80] Within the treaty, Magnús Hákonarson, King of Norway (d. 1280) ceded Mann and the Isles to Alexander, who in turn agreed to pay 4,000 merks sterling over four years, and in addition to pay 100 merks sterling in perpetuity. Other conditions stipulated that the inhabitants of the islands would be subject to laws of Scotland; that they were not to be punished for their actions previous to the treaty; and that they were free to remain or leave their possessions peacefully.[81] In 1266, the Chronicle of Lanercost records that Alexander ruled Mann through appointed bailiffs; Scottish exchequer accounts record that the Sheriff of Dumfries was given allowance for maintaining seven Manx hostages.[82]

In 1275, Magnús Óláfsson's illegitimate son, Guðrøðr, led a revolt on Mann and attempted to establish himself as king.[83] According to the Chronicle of Mann and the Chronicle of Lanercost, a Scottish fleet landed on Mann on 7 October, and early the next morning the revolt was crushed as the Scots routed the rebels.[84][note 11] Guðrøðr may very well have been slain in the defeat,[87] although one source, the Annals of Furness, states that he, his wife and his followers escaped the carnage to Wales.[88][note 12]

By the end of the 13th century, the islands once ruled by Magnús, and the Crovan dynasty before him, were incorporated into the Scottish realm. In 1293, the parliament of John, King of Scots (d. 1314) established three new sheriffdoms within his kingdom. One of these three, the Sheriffdom of Skye, was granted to Uilleam, Earl of Ross (d. 1323). This sheriffdom included the seaboard north of Ardnamurchan (Wester Ross and Kintail), and the islands of Skye, Lewis, Uist, Barra, Eigg, and Rum. It is possible that parts of the sheriffdom may have been taken over earlier, sometime after the dismantling of the Kingdom of Mann and the Isles.[91]

Ancestry

Ancestors of Magnus Olafsson 16. Guðrøðr "Crovan" (d. 1095)[92][note 13]

King of the Isles, King of Dublin[95]8. Óláfr Guðrøðarson (d. 1153)

King of the Isles4. Guðrøðr Óláfsson (d. 1187)

King of the Isles18. Fergus (d. 1161)[99][note 15]

Lord of Galloway[99]9. Affraic[96][note 14] 19. [unnamed][99][note 16] 2. Óláfr Guðrøðarson (d. 1237)

King of the Isles20. Muirchertach Mac Lochlainn (d. 1166)[104][note 17]

High King of Ireland, King of Cenél nEógain[104]10. Niall Mac Lochlainn[103]

King of Cenél nEógain[103]5. Finnguala[103] 1. Magnús Óláfsson (d. 1265)

King of Mann and the Isles6. Ferchar (d. circa 1251)

Earl of Ross3. Christina Notes

- ^ On Óláfr's death in 1237, he was succeeded by his son, Haraldr (d. 1248). According to the Chronicle of Mann, Haraldr was was only fourteen years' old at the time of his father's death. This dates Haraldr's birth to about the time of the marriage of Óláfr and Christina.[3]

- ^ The names of Somairle and his descendants are rendered in Mediaeval Gaelic; the other names are rendered in Old Norse.

- ^ It is not known how the descendants of Rögnvaldr Guðrøðarson (d. 1229) styled themselves.[12] Contradicting contemporary sources may indicate that Óláfr Guðrøðarson (d. 1237) had a fourth son, named Guðrøðr.[13]

- ^ For example, the Scots who took part in the attack are said to have "taken the little children, and laid them on their spear-points, and shook their spears until they brought the children down to their hands; and so threw them away dead".[33]

- ^ When the embassy attempted to leave Norway without permission, Hákon held the Scots against their will for a time.[34]

- ^ The Mediaeval Gaelic personal name Murchad is rendered in Old Norse as Margaðr.[42] Although several scholars have identified Murchad as an otherwise unknown brother of Áengus, he is more likely to have been a member of the meic Suibne[43]—a recently dispossessed-kindred, descended from Murchad's grandfather, Suibne (d. 13th century).[44] In 1262, Skipness and parts of Knapdale, Kintyre, and Cowal, belonging to Dubgall mac Suibne (Murchad's uncle), passed into the hands of Walter Stewart, Earl of Menteith (d. circa 1293) under uncertain circumstances. The meic Suibne sought to reacquire their ancestral lands as late as the first decade in the 14th century, before settling in Ireland for good.[45]

- ^ The place name "Tarbet" is derived from the Gaelic tairbeart, meaning "(place by a) portage".[53]

- ^ The saga states that Ruaidrí claimed Bute as his birthright; he slaughtered the garrison of the island's castle who had surrendered under truce, and afterwards viciously harried the surrounding district.[60] Ruaidrí may have been a son of Óspakr Ögmundsson, King in the Isles (d. 1230), a supposed member of the meic Somairle, whom Hákon had recognised as king in the Isles.[61] In 1230, Hákon supplied Óspakr with invasion fleet which sailed down through the Hebrides to Bute. Although the force seized Rothesay Castle from the Scots, Óspakr died soon after from wounds suffered in the assault.[62]

- ^ This record is the earliest mention of the castle in the chronicle.[76]

- ^ The three kings are Magnús' brother Rögnvaldr, and their father, Óláfr.[70]

- ^ Both chronicle's accounts of the revolt are derived from the same original source.[85] One of the Scots magnates present at the battle was Alastair mac Eógain, Lord of Argyll (d. 1310), son of Magnús' father-in-law.[86]

- ^ The Annals of Furness, although an English source, have links to Mann.[89] The annals date to about 1290, when they were copied from contemporary notes.[90]

- ^ Guðrøðr's ancestry is uncertain, although he very well may have been an Uí Ímair dynast.[93] The epithet "crovan" is likely a Latinised form of a Gaelic or Norse epithet, and may refer to a deformity of the hands.[94]

- ^ Óláfr Guðrøðarson (d. 1153) is known to have had at least two wives: Ingibjörg Hákonardóttir and Affraic ingen Fergus. Ingibjörg was a daughter of Hákon Pálsson, Earl of Orkney (d. circa 1126). Affraic was a daughter of Fergus, Lord of Galloway.[97] Ingibjörg was likely Óláfr's first wife.[98] Guðrøðr's mother was most likely Affraic.[96]

- ^ Fergus' ancestry is uncertain.[99]

- ^ Affraic's mother was an unnamed illegitimate daughter of Henry I, King of England, Duke of Normandy (d. 1135).[100] Henry was the son of William I, King of England, Duke of Normandy (d. 1087),[101] and his wife Matilda (d. 1083), daughter of Baldwin V, Count of Flanders.[102]

- ^ Muirchertach was the son of Niall Mac Lochlainn, who was the son of Domnall MacLochlainn.[104]

References

- Footnotes

- ^ Munch; Goss 1874: pp. 108–109.

- ^ McDonald 2007: p. 79 fn 48. See also: Munro; Munro 2004.

- ^ McDonald 2007: p. 79 fn 48.

- ^ McDonald 2007: pp. 70–71.

- ^ Duffy 2004c. See also: McNamee 2004.

- ^ McNamee 2004.

- ^ McDonald 2007: pp. 87–88, 151–152.

- ^ McDonald 2007: p. 88.

- ^ Anderson 1922: p. 567 fn 2.

- ^ McDonald 2007: p. 88–89.

- ^ McDonald 2007: p. 27. See also: Sellar 2004b. See also: Sellar 2000: pp. 192, 194. See also: Duncan; Brown 1956–1957: pp. 196–197, 200.

- ^ a b Sellar 2000: pp. 192–193.

- ^ McDonald 2007: pp. 106–107.

- ^ Duncan; Brown 1956–1957: pp. 196–197.

- ^ Woolf 2004: p. 108.

- ^ a b c Sellar 2004b

- ^ Higgitt 2000: p. 19.

- ^ Beuermann 2010: p. 102.

- ^ Beuermann 2010: p. 108. See also: Sellar 2004b. See also: Anderson 1922: pp. 554–555.

- ^ a b c McDonald 2007: p. 89. See also: Anderson 1922: pp. 567–569. See also: Munch; Goss 1874: pp. 104–109.

- ^ a b McDonald 2007: p. 89.

- ^ Sellar 2004b. See also: Stringer 2004. See also: Brown 2004: p. 81. See also: McDonald 1997: p. 104.

- ^ McDonald 1997: p. 104. See also: Anderson 1922: pp. 567–569. See also: Munch; Goss 1874: pp. 104–109.

- ^ McDonald 2007: p. 89. See also: Munch; Goss 1874: p. 206 fn 49.

- ^ Carpenter 2008. See also: McDonald 2007: p. 89. See also: Sweetman 1875: p. 478 (#3206).

- ^ McDonald 2007: p. 89. See also: Anderson 1922: p. 573, See also: Munch; Goss 1874: pp. 108–109.

- ^ a b McDonald 2007: pp. 89–90.

- ^ McDonald 2007: pp. 89–90. See also: Anderson 1922: p. 578. See also: Munch; Goss 1874: pp. 108–109.

- ^ Smith 2004. See also: McDonald 1997: p. 104 fn 4.

- ^ McDonald 2007: pp. 40, 84, 210.

- ^ Stringer 2004.

- ^ a b Munro; Munro 2004. See also: Reid 2004. See also: McDonald 1997: pp. 106–107. See also: Duncan; Brown 1956–1957: p. 212.

- ^ McDonald 1997: p. 106. See also: Anderson 1922: pp. 605–606.

- ^ Power 2005: p. 50. See also: Anderson 1922: pp. 601–602.

- ^ Power 2005: pp. 50–53.

- ^ McDonald 1997: p. 107. See also: Anderson 1922: p. 607.

- ^ a b McDonald 1997: p. 108. See also: Anderson 1922: pp. 615–616.

- ^ McDonald 1997: p. 108.

- ^ Sellar 2000: pp. 194, 201, 207. See also: McDonald 1997: p. 109. See also: Anderson 1922: p. 617.

- ^ Sellar 2000: p. 194. See also: McDonald 1997: p. 109.

- ^ McDonald 1997: p. 109. See also: Anderson 1922: p. 618.

- ^ Ó Cuív 1988: p. 80.

- ^ Sellar 2000: pp. 206–207.

- ^ Woolf 2005. See also: Ewart; Triscott 1996: p 518.

- ^ McDonald 2005: p. 189 fn 36. See also: Brown 2004: p. 82. See also: Barrow 2004. See also: Ewart; Triscott 1996: p 518. See also: Barrow 1973: p. 373.

- ^ McDonald 1997: p. 110. See also: Anderson 1922: pp. 619–620.

- ^ McDonald 1997: p. 110.

- ^ McDonald 1997: pp. 111–112. See also: Anderson 1922: p. 617.

- ^ McDonald 1997: pp. 111–112. See also: Anderson 1922: pp. 622–623.

- ^ McDonald 1997: p. 112. See also: Anderson 1922: pp. 622–625.

- ^ McDonald 1997: p. 112. See also: Anderson 1922: pp. 625–626, 625 fn 7.

- ^ Forte; Oram; Pedersen 2005: p. 258. See also: Barrow 1981: p. 117.

- ^ Tarbet, Encyclopedia.com (www.encyclopedia.com), http://www.encyclopedia.com/doc/1O40-Tarbet.html, retrieved 21 September 2011. This webpage is a partial transcription of: Mills, Anthony David (2003), A Dictionary of British Place-Names, Oxford University Press.

- ^ McDonald 1997: p. 112. See also: Anderson 1922: pp. 625–626.

- ^ McDonald 1997: p. 112. See also: Rixson 1998: p. 73.

- ^ Sellar 2000: p. 206. Barrow 1981: p. 117.

- ^ Forte; Oram; Pedersen 2005: pp. 258–260.

- ^ a b McDonald 1997: pp. 113–114.

- ^ McDonald 1997: p. 114. See also: Anderson 1922: pp. 634–635.

- ^ McDonald 1997: pp. 110–111. See also: Anderson 1922: pp. 620–622.

- ^ Sellar 2000: pp. 194, 202. See also: McDonald 1997: pp. 110–111. See also: Duncan; Brown 1956–1957: p. 203 fn 5.

- ^ Forte; Oram; Pedersen 2005: pp. 250–252. 258. See also: McDonald 1997: p. 90. See also. Anderson 1922: pp. 473–477.

- ^ a b Barrow 1981: pp. 118–119.

- ^ Anderson 1922: p. 635.

- ^ McDonald 2007: pp. 53, 207, 222. See also: Brown 2004: pp. 83–85. See also: McDonald 1997: p. 115.

- ^ Paton; Reid 2004. See also: Young 2004a. See also: Young 2004b.

- ^ McDonald 1997: p. 116. See also: Anderson 1922: pp. 648–649. See also: Skene 1872a: pp. 300–301. See also: Skene 1872b: p. 296.

- ^ Brown 2004: p. 84. See also: McDonald 1997: p. 116.

- ^ Brown 2004: p. 84.

- ^ a b c McDonald 2007: p. 201. See also: Kermode 2005: p. 6. See also: Kermode; Herdman 1904: p. 86.

- ^ McDonald 2007: p. 202.

- ^ McDonald 2007: p. 215. See also: McDonald 2005: p. 193 fn 50. See also: Anderson 1922: pp. 587, 587 fn 1. See also: Munch; Goss 1874: pp. 108–109.

- ^ McDonald 2005: p. 193 fn 50. See also: Oliver 1861: p. 86. See also: Rymer; Sanderson; Holmes 1739: pt 2, p. 12.

- ^ McDonald 2007: pp. 89–90. See also: Sellar 2000: p. 210.

- ^ McDonald 2007: pp. 89–90. See also: Sellar 2000: p. 210. See also: Anderson 1922: pp. 653, 653 fn 1. See also: Munch; Goss 1874: pp. 94–95.

- ^ McDonald 2007: p. 211.

- ^ Munch; Goss 1874: p. 206.

- ^ Sellar 2004b. See also: Higgitt 2000: p. 19.

- ^ McDonald 2007: p. 90. See also: Howlett 1895: p. 549.

- ^ McDonald 1997: pp. 119–121.

- ^ Lustig 1979: pp. 44–45.

- ^ Duncan; Brown 1956–1957: p. 214. See also: Anderson 1922: p. 657.

- ^ McDonald 2007: pp. 54. See also: Sellar 2000: p. 210.

- ^ McDonald 2007: pp. 54. See also: Anderson 1922: pp. 672–673. See also: Munch; Goss 1874: pp. 110–111.

- ^ Anderson 1922: p. 673 fn 1.

- ^ Sellar 2004a.

- ^ Sellar 2000: p. 210.

- ^ McDonald 2007: p. 107. See also: Anderson 1908: pp. 382–383. See also: Howlett 1895: p. 570.

- ^ Sellar 2000: p. 210 fn 114.

- ^ Anderson 1908: p. 382 fn 1. See also: Howlett 1895: p. lxxxviii.

- ^ Stell 2005. See also: Brown 2004: p. 85. See also: Munro; Munro 2004. See also: McDonald 1997: p. 131. See also: Duncan; Brown 1956–1957: p. 216.

- ^ McDonald 2007: p. 64. See also: Duffy 2004a. See also: Sellar 2000: p. 192.

- ^ McDonald 2007: pp. 61–62. See also: Duffy 2004a.

- ^ McDonald 2007: p. 64, p. 64 fn 34. See also: Duffy 2004a.

- ^ Sellar 2000: p. 192.

- ^ a b Duffy 2004a.

- ^ Duffy 2004a. See also: Crawford 2004.

- ^ Anderson 1922: p. 136 fn 2.

- ^ a b c d Oram 2004.

- ^ Oram 2004. See also: Hollister 2004.

- ^ Bates 2004.

- ^ van Houts 2004.

- ^ a b c McDonald 2007: p. 71.

- ^ a b c Duffy 2004b.

- Bibliography

- Anderson, Alan Orr, ed. (1908), Scottish annals from English chroniclers, a.d. 500 to 1286, David Nutt, http://www.archive.org/details/scottishannalsfr00andeuoft.

- Anderson, Alan Orr, ed. (1922), Early sources of Scottish history: a.d. 500 to 1286, 2, Oliver and Boyd, http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924077097958.

- Barrow, Geoffrey Wallis Steuart (1973), The kingdom of the Scots: government, church and society from the eleventh to the fourteenth century, St. Martin's Press.

- Barrow, Geoffrey Wallis Steuart (1981), Kingship and unity: Scotland 1000–1306, University of Toronto Press.

- Barrow, Geoffrey Wallis Steuart (2004), "Stewart family (per. c.1110–c.1350), nobility" (Subscription or UK public library membership required), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/49411, http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/49411, retrieved 5 July 2011.

- Bates, David (2004), "William I [known as William the Conqueror] (1027/8–1087), king of England and duke of Normandy" (Subscription or UK public library membership required), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online May 2011 ed.), doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/29448, http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/29448, retrieved 5 July 2011.

- Brown, Michael (2004), The wars of Scotland, 1214–1371, The New Edinburgh History of Scotland, Edinburgh University Press, ISBN 9780748612383.

- Beuermann, Ian (2010), "'Norgesveldet?' south of Cape Wrath?", in Imsen, Steinar, The Norwegian domination and the Norse world c. 1100–c. 1400, Norgesveldt Occasional Papers (Trondheim Studies in History), Tapir Academic Press, pp. 99–123, ISBN 978-8251925631.

- Carpenter, David A. (2008), "John fitz Geoffrey (c.1206–1258)" (Subscription or UK public library membership required), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (revised, online Jan 2008 ed.), doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/38271, http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/38271, retrieved 5 September 2011.

- Crawford, Barbara Elizabeth (2004), "Magnús Erlendsson, earl of Orkney [St Magnus] (1075/6–1116?), patron saint of Orkney" (Subscription or UK public library membership required), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/65444, http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/65444, retrieved 5 September 2011.

- Duffy, Seán (2004a), "Godred Crovan [Guðrøðr, Gofraid Méránach] (d. 1095), king of Man and the Isles" (Subscription or UK public library membership required), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/50613, http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/50613, retrieved 5 July 2011.

- Duffy, Seán (2004b), "Mac Lochlainn [Ua Lochlainn], Muirchertach (d. 1166), high-king of Ireland" (Subscription or UK public library membership required), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/20745, http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/20745, retrieved 5 July 2011.

- Duffy, Seán (2004c), "Ragnvald [Rögnvaldr, Reginald, Ragnall] (d. 1229), king of Man and the Isles" (Subscription or UK public library membership required), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/50617, http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/50617, retrieved 5 July 2011.

- Duncan, Archibald Alexander McBeth; Brown, A. L. (1956–1957), "Argyll and the Isles in the earlier middle ages" (pdf), Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland (Society of Antiquaries of Scotland) 90: 192–220, http://ads.ahds.ac.uk/catalogue/adsdata/PSAS_2002/pdf/vol_090/90_192_220.pdf.

- Ewart, Gordon; Triscott, Jon (1996), "Archaeological excavations at Castle Sween, Knapdale, Argyll & Bute, 1989–90" (pdf), Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland 126: 517–557, http://ads.ahds.ac.uk/catalogue/adsdata/arch-352-1/dissemination/pdf/vol_126/126_517_557.pdf

- Forte, Angelo; Oram, Richard; Pedersen, Frederik (2005), Viking empires, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 13-978-0-521-82992-2.

- Higgitt, John (2000), The murthly hours: devotion, literacy and luxury in Paris, England and the Gaelic west, University of Toronto Press, ISBN 9780802047595.

- Hollister, C. Warren (2004), "Henry I (1068/9–1135), king of England and lord of Normandy" (Subscription or UK public library membership required), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/12948, http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/12948, retrieved 5 July 2011.

- Howlett, Richard, ed. (1895), Chronicles of the reigns of Stephen, Henry II., and Richard I., 2, Longman & Co, http://www.archive.org/details/chroniclesofreig02howl.

- Kermode, Philip Moore Callow; Herdman, William Abbott (1904), Illustrated notes on Manks antiquities, http://www.archive.org/details/illustratednotes00kermrich.

- Kermode, Philip Moore Callow (2005) [1907], Manx crosses or the inscribed and sculptured monuments of the Isle of Man from about the end of the fifth to the beginning of the thirteenth century, Elibron Classics, 1, Adamant Media Corporation, ISBN 9781402164026.

- Lustig, Richard L. (1979), "The treaty of Perth: a re-examination", The Scottish Historical Review 58: 35–57, JSTOR 25529318.

- McDonald, Russell Andrew (1997), The kingdom of the Isles: Scotland's western seaboard, c.1100–c.1336, Scottish Historical Monographs, Tuckwell Press, ISBN 1 898410 85 2.

- McDonald, Russell Andrew (2005), "Coming in from the margins: the descendants of Somerled and cultural accommodation in the Hebrides, 1164–1317", in Smith, Brendan, Britain and Ireland, 900–1300: insular responses to medieval European change, Cambridge University Press, pp. 179–198, ISBN 0-511-03855-0.

- McDonald, Russell Andrew (2007), Manx kingship in its Irish sea setting, 1187–1229: king Rǫgnvaldr and the Crovan dynasty, Four Courts Press, ISBN 978-1-84682-047-2.

- McNamee, Colm (2004), "Olaf [Olaf the Black, Olaf Godredsson] (1173/4–1237), king of Man and the Isles" (Subscription or UK public library membership required), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (May 2005 ed.), doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/20672, http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/20672, retrieved 5 July 2011.

- Munch, Peter Andreas; Goss, Alexander, eds. (1874), Chronica regvm Manniæ et Insvlarvm: the chronicle of Man and the Sudreys; from the manuscript codex in the British Museum; with historical notes, 1, printed for the Manx Society, http://www.archive.org/details/chronicaregvmma00gossgoog.

- Munro, Robert William; Munro, Jean (2004), "Ross family (per. c.1215–c.1415), nobility" (Subscription or UK public library membership required), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online October 2008 ed.), doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/75447, http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/75447, retrieved 5 July 2011.

- Ó Cuív, Brian (1988), "Personal names as an indicator of relations between native Irish and settlers in the Viking period", in Bradley, John, Settlement and society in medieval Ireland: studies presented to F.X. Martin, Boethius Press, pp. 79–88, ISBN 9780863141430.

- Oliver, J. R., ed. (1861), Monumenta de Insula Manniæ, 2, Printed for the Manx Society, http://www.archive.org/details/publications77socigoog.

- Oram, Richard D. (2004), "Fergus, lord of Galloway (d. 1161), prince" (Subscription or UK public library membership required), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/49360, http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/49360, retrieved 5 July 2011.

- Paton, Henry; Reid, Norman H. (2004), "William, fifth earl of Mar (d. in or before 1281), magnate" (Subscription or UK public library membership required), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (revised ed.), doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/18023, http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/18023, retrieved 15 September 2011.

- Power, Rosemary (2005), "Meeting in Norway: Norse-Gaelic relations in the kingdom of Man and the Isles, 1090–1270" (pdf), Saga-Book (Viking Society for Northern Research) 29: 5–66, ISSN 0305-9219, http://www.vsnrweb-publications.org.uk/Saga-Book%20XXIX.pdf.

- Reid, Norman H. (2004), "Alexander III (1241–1286), king of Scots" (Subscription or UK public library membership required), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online May 2011 ed.), doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/323, http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/323, retrieved 5 July 2011.

- Rymer, Thoma; Sanderson, Roberto; Holmes, Georgii, eds. (1739), Fœdera, conventiones, litteræ et cujuscunque generis acta publica, inter reges Angliæ at alios quosvis imperatores, reges, pontifices, principes, vel communitates habita aut tractata, 1, Joannem Neaulme, http://www.archive.org/details/fderaconventione01ryme.

- Rixson, Denis (1998), The west highland galley, Birlinn, ISBN 1 874744 86 6.

- Sellar, William David Hamilton (2000), "Hebridean sea kings: The successors of Somerled, 1164–1316", in Cowan, Edward J.; McDonald, Russell Andrew, Alba: Celtic Scotland in the middle ages, Tuckwell Press, pp. 187–218, ISBN 1-86232-151-5.

- Sellar, William David Hamilton (2004a), "MacDougall, Alexander, lord of Argyll (d. 1310), magnate" (Subscription or UK public library membership required), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/49385, http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/49385, retrieved 5 July 2011.

- Sellar, William David Hamilton (2004b), "MacDougall, Ewen, lord of Argyll (d. in or after 1268), king in the Hebrides" (Subscription or UK public library membership required), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/49384, http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/49384, retrieved 5 July 2011.

- Skene, William Forbes, ed. (1872a), John of Fordun's chronicle of the Scottish nation, 1, Edmonston and Douglas, http://www.archive.org/details/johannisdefordun01ford.

- Skene, William Forbes, ed. (1872b), John of Fordun's chronicle of the Scottish nation, 2, Edmonston and Douglas, http://www.archive.org/details/johannisdefordun02ford.

- Smith, J. B. (2004), "Llywelyn ap Gruffudd (d. 1282), prince of Wales" (Subscription or UK public library membership required), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online January 2008 ed.), doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/16875, http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/16875, retrieved 9 July 2011.

- Stell, G. P. (2005), "John [John de Balliol (c.1248x50–1314), king of Scots"] (Subscription or UK public library membership required), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online October 2005 ed.), doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/1209, http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/1209, retrieved 6 September 2011.

- Stringer, Keith J. (2004), "Alexander II (1198–1249), king of Scots" (Subscription or UK public library membership required), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/322, http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/322, retrieved 5 July 2011.

- Sweetman, Henry Savage, ed. (1875), Calendar of documents relating to Ireland, Longman & Co, http://www.archive.org/details/calendardocumen00sweegoog.

- van Houts, Elisabeth (2004), "Matilda [Matilda of Flanders] (d. 1083), queen of England, consort of William I" (Subscription or UK public library membership required), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online May 2008 ed.), doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/18335, http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/18335, retrieved 28 September 2011.

- Woolf, Alex (2004), "The age of sea-kings, 900–1300", in Omand, Donald, The Argyll book, Birlinn, pp. 94–109, ISBN 1-84158-253-0.

- Woolf, Alex (2005), "The origins and ancestry of Somerled: Gofraid mac Fergusa and 'The Annals of the Four Masters'", Mediaeval Scandinavia 15: 199–213.

- Young, Alan (2004a), "Comyn, Alexander, sixth earl of Buchan (d. 1289), baron and administrator" (Subscription or UK public library membership required), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/6042, http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/6042, retrieved 15 September 2011.

- Young, Alan (2004b), "Durward, Alan (d. 1275), magnate" (Subscription or UK public library membership required), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online October 2006 ed.), doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/8328, http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/8328, retrieved 15 September 2011.

External links

Regnal titles Preceded by

Haraldr Guðrøðarson

(first cousin once removed)King of Mann and the Isles

1254–1265Extinct Categories:- 1265 deaths

- 13th-century births

- 13th-century monarchs in Europe

- Crovan dynasty

- Monarchs of the Isle of Man

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.