- Damnatio ad bestias

-

Ignatius of Antioch being torn by lions

Ignatius of Antioch being torn by lions

Damnatio ad bestias (Latin for "condemnation to beasts") was a form of capital punishment in which the condemned were maimed on the circus arena or thrown to a cage with animals, usually lions. It was brought to ancient Rome around the 2nd century BC from Asia, where a similar penalty existed from at least the 6th century BC. In Rome, damnatio ad bestias was used as entertainment and was part of the inaugural games of the Flavian Amphitheatre. In the 1st–3rd centuries AD, this penalty was mainly applied to the worst criminals and early Christians (Latin: christianos ad leones, "Christians to the lions"). It was abolished in 681 AD.

Contents

History

Asia

Daniel in the Lion's Den (c. 1615) by Peter Paul Rubens. Oil on canvas, 224×330 cm, National Gallery of Art, Washington

Daniel in the Lion's Den (c. 1615) by Peter Paul Rubens. Oil on canvas, 224×330 cm, National Gallery of Art, Washington

One of the earliest accounts of damnatio ad bestias is a Bible story dated to the 6th century BC. Prophet Daniel was thrown to the lions by King Darius I for disobedience but miraculously escaped from death. The accusers of Daniel and their families were then subjected to the same treatment and maimed instantly.[1]

The exact purpose of the early damnatio ad bestias is not known and might have been a religious sacrifice rather than a legal punishment,[2] especially in the regions where lions existed naturally and were revered by the population, such as Africa and parts of Asia. For example, Egyptian mythology had a lion-like god, Amat, who devoured human's souls, as well as other lion-like deities. There are also accounts of feeding lions and crocodiles with humans, both dead and alive, in Ancient Egypt and Libya.[3][4] The tradition of human sacrifice (including children) existed, for example, in Carthage at the end of 4th century to the middle of the 2nd century BC, until the fall of the Carthaginian empire.[5][6][7]

As a punishment, damnatio ad bestias is mentioned by historians of Alexander's campaigns. For example, in Central Asia, a Macedonian named Lysimachus, who spoke before Alexander for a person condemned to death, was himself thrown to a lion, but overcame him with his bare hands and became one of Alexander's favorites.[8] During the Mercenary War, Carthaginian general Hamilcar Barca threw prisoners to the beasts,[9] whereas Hannibal forced Romans captured in the Punic Wars to fight each other, and the survivors had to stand against elephants.[10]

Ancient Rome

Lions were rare in Ancient Rome, and human sacrifice was banned there by Numa Pompilius in the 7th century BC, according to legend. Damnatio ad bestias appeared there not as a spiritual practice but rather a spectacle. In addition to lions, other animals were used for this purpose, including bears, leopards, black panthers and bulls. It was combined with gladiatorial combat and was first featured at the Roman Forum and then transferred to the amphitheaters.

Terminology

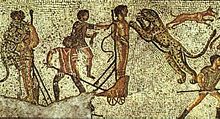

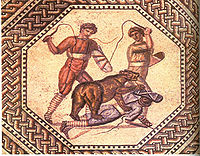

Whereas the term damnatio ad bestias is usually used in a broad sense, historians distinguish two subtypes: objicĕre bestiis (to devour by beasts) where the humans are defenseless, and damnatio ad bestias, where the punished are both expected and prepared to fight.[11] In addition, there were professional beast fighters trained in special schools, such as the Roman Morning School, which received its name by the timing of the games.[12] These schools taught not only fighting but also the behavior and taming of animals.[13] The fighters were released into the arena dressed in a tunic and armed only with a spear (occasionally with a sword). They were sometimes assisted by venators (hunters),[14] who used bows, spears and whips. Such group fights were not human executions but rather staged animal fighting and hunting. Various animals were used, such as hyena, elephant, wild boar, buffalo, lynx, giraffe, ostrich, deer, hare, antelope and zebra. The first such staged hunting (Latin: venatio) featured lions and panthers, and was arranged by Marcus Fulvius Nobilior in 186 BC at the Circus Maximus on the occasion of the Greek conquest of Aetolia.[15][16] The Colosseum and other circuses still contain underground hallways that were used to lead the animals to the arena.

History and description

The custom of submitting criminals to lions was brought to ancient Rome by two commanders, Lucius Aemilius Paullus Macedonicus, who defeated the Macedonians in 186 BC, and his son Scipio Aemilianus, who conquered the African city of Carthage in 146 BC.[17] It was borrowed from the Carthaginians and was originally applied to such criminals as defectors and deserters in public, its aim being to prevent crime through intimidation. It was rated as extremely useful and soon became a common procedure in Roman criminal law.[2][18] The sentenced were tied to columns or thrown to the animals, practically defenseless (i.e. objicĕre bestiis).

Some documented examples of damnatio ad bestias in Ancient Rome include the following. Strabo witnessed[19] the execution of the rebel slaves' leader Selur.[16] The bandit Lavreol was crucified and then devoured by an eagle and a bear, as described by the poet Martial in his Book of Spectacles.[20] Such executions were also documented by Seneca (On anger, III 3), Apuleius (The Golden Ass, IV, 13), Titus Lucretius Carus (On the Nature of things) and Petronius Arbiter (Satyricon, XLV). Cicero was indignant that a man was thrown to the beasts to amuse the crowd just because he appeared ugly.[21][22] Suetonius wrote that when the price of meat was too high, Caligula ordered prisoners, with no discrimination as to their crimes, to be fed to circus animals.[23] Pompey used damnatio ad bestias for showcasing battles and, during his second consulate (55 BC), staged a fight between heavily armed gladiators and 18 elephants.[10][24][25]

The most popular animals were lions, which were imported to Rome in significant numbers specifically for damnatio ad bestias.[16] Bears, brought from Gaul and Germany, were less popular.[26][27] Local municipalities were ordered to provide food for animals in transit and not delay their stay for more than a week.[16][28] Some historians believe that the mass export of animals to Rome damaged wildlife in North Africa.[29]

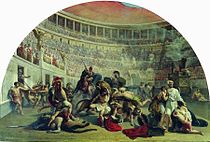

Execution of Christians

Christian Martyrs in the Colosseum by Konstantin Flavitsky

Christian Martyrs in the Colosseum by Konstantin Flavitsky

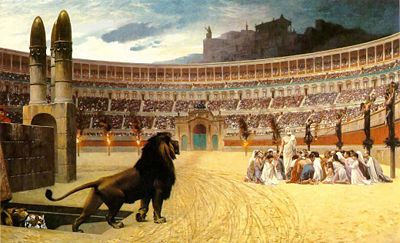

The use of damnatio ad bestias against Christians began in the 1st century AD. Tacitus describes that during the first persecution of Christians under the reign of Nero (after the Fire of Rome in 64), people were wrapped in animal skins (called tunica molesta) and thrown to dogs.[30] This practice was followed by other emperors who moved it into the arena and used larger animals. Application of damnatio ad bestias to Christians was intended to equate them with the worst criminals, who were usually punished this way.[31]

According to Roman laws, Christians were:[32]

- Offenders of their Majesty (majestatis rei)

- For their worships Christians gathered in secret and at night, making unlawful assembly, and participation in such collegium illicitum or coetus nocturni was equated with a riot.

- Refusal to honor images of the emperor by libations and incense

- Dissenters from the state gods (άθεοι, sacrilegi)

- Followers of magic prohibited by law (magi, malefici)

- Confessors of a religion unauthorized by the law (religio nova, peregrina et illicita), according to the Twelve Tables).

Apart from these specific violations, Christians fell under special government edicts, which were published from 104 AD and targeted anyone who identified themselves as a Christian.[32] Christians were made public scapegoats for any unexplained natural disasters, such as drought, famine, pestilence, earthquakes and floods.[33][34]

The spread of the practice of throwing Christians to beasts was reflected by the Christian writer Tertullian (2nd century). He wrote that Christians started avoiding theaters and circuses, which were associated with the place of their torture.[35] The persecution of Christians ceased by the 4th century. The Edict of Milan (313) gave them freedom of religion, though according to Holy Scripts, Theodosia of Tyre was thrown to lions in 303 and St. Vitus in 307.

Penalty for other crimes

Roman laws, which are known to us through the Byzantine collections, such as Code of Theodosius and Code of Justinian, defined what criminals could be thrown to beasts (or condemned by other means). They included

- Deserters from the army[36]

- Those who employed sorcerers to harm others, during the reign of Caracalla.[37] This law was re-established in 357 AD by Constantius II[38]

- Poisoners; by the law of Cornelius, patricians were beheaded, plebeians thrown to lions and slaves crucified[36][39]

- Counterfeiters, who could also be burned alive[36][40]

- Political criminals. For example, after the overthrow and assassination of Commodus, the new emperor threw to lions both the servants of Commodus and Narcissus who strangled him – even though Narcissus brought the new emperor to power, he committed a crime of murdering the previous one[41] The same punishment was applied to Mnesteus who organized the assassination of Emperor Aurelian.[42]

- Patricides, who were normally drowned in a leather bag filled with snakes (poena cullei), but could be thrown to beasts if a suitable body of water was not available[36]

- Instigators of uprisings, who were either crucified, thrown to beasts or exiled, depending on their social status[43]

- Those who kidnapped children for ransom, according to the law of 315 by the Emperor Constantine the Great,[38] were either thrown to beasts or beheaded.

The Christian Martyrs' Last Prayer by Jean-Léon Gérôme

The Christian Martyrs' Last Prayer by Jean-Léon Gérôme

The sentenced was deprived of civil rights; he could not write a will, and his property was confiscated.[44][45] Exception from damnatio ad bestias was given to military servants and their children.[36] Also, the law of Petronius (Lex Petronia) of 61 AD forbade employers to send their slaves to be eaten by animals without a judicial verdict. Local governors were required to consult a Rome deputy before staging a fight of skilled gladiators against animals.[46]

The practice of damnatio ad bestias was abolished in Rome only in 681 AD.[11] It was used once after that in the Byzantine Empire: in the 9th century, when a group of disgraced generals was arrested for plotting conspiracy against emperor Basil II, they were imprisoned and their property seized, but the royal eunuch who assisted them was thrown to lions.[47] Also, a bishop of Saare-Lääne was sentencing criminals to damnatio ad bestias at the Bishop's Castle in modern Estonia in the Middle Ages.[48]

Notable victims

- Ignatius of Antioch (107 AD, Rome)[49]

- Germanicus and 10 Christians from Alaşehir (mentioned in the description of the martyrdom by Polycarp of Smyrna)

- Saint Glyceria (141 AD, Trayanopolis, Thrace)[50]

- Martyr Euphemia. Whereas lions refused to maim her, and licked her feet, a bear mortally wounded her.

- Perpetua and Felicity, Satur and their relatives (203 AD, presumably Carthage)

Miraculously survived

- Ab early description of escape from the death by devouring is in the story of Daniel in the Book of Daniel (ca. 2nd century BC).

- The Greek writer Apion (1st century AD) tells the story of a slave Androcles (during the Caligula's rule) who was caught after fleeing his master and thrown to a lion. The lion spared him, which Androcles explained by saying that he pulled a thorn of the paw of the very same lion when hiding in Africa, and the lion remembered him.[51]

- Paul (according to apocryphas and the medieval legends, based on his note "when I have fought with beasts at Ephesus", 1 Corinthians, 15:32)

- Archelaus (during Diocletian's rule)

- St. Blandina (177 AD, Lyon) – a Christian martyr and a slave thrown to lions together with 48 other Christians. Their relics are buried in Lyon.

- Saint Eustace (114 AD, Rome)

- Martyr Eleutherius of Constantinople (Hadrian's rule, Rome)

- Tatiana of Rome (226 AD)

- Saint Thecla (Antioch). Leon became her attribute in iconography

- Saint Vitus (303 AD)

- Vasily New (9th century, Byzantium)[52] – was sentenced for sorcery, not for Christianity

- Rabbi Chaim ibn Attar[53]

- Harald Hardrada – strangled the lion and fled from Constantinople during his Wandering in the East.[54]

- An anecdotal escape is reported in the biography of Emperor Gallienus (in the Augustan History).[55] A man was caught after selling the emperor's wife glass instead of gems. Gallienus sentenced him to face lions, but ordered to that a capon rather than a lion be let into the arena. The emperor's herald then proclaimed "he has forged, and was treated the same". The merchant was then released.

Perception of damnatio ad bestias in religion

In addition to the story of the unsuccessful execution of Daniel in the Old Testament, lions devouring people are referred to as an instrument of divine wrath: in the 4th plague of Egypt (according to one interpretation[56]) wild animals flooded the cities and devoured Egyptians but not Jews. Among Christians, the death through damnatio ad bestias gradually ceased to be shameful and acquired a kind of honorable purification through martyrdom.[57][58]

Description in popular culture

Literature

- Tommaso Campanella in his utopia , "The City of the Sun" suggests using damnatio ad bestias as a form of punishment.[59]

- Bernard Shaw. Androcles and Lion

- Henryk Sienkiewicz. Quo Vadis

- Lindsey Davis. Two for the Lions. A novel of life in Ancient Rome, series Marcus Didius Falco

Music

- Ottorino Respighi, The Roman Triptych, fragment Circene: Christian martyrs in the arena.

- Polish blackened death metal band Behemoth: the song Christians to the Lions

- American death metal band Morbid Angel: the song Lion's Den

Film

- Fights against wild animals in the arena of the Roman Colosseum were displayed in Gladiator (2000) and other films.

See also

References

- ^ Daniel 6 / Hebrew Bible in English / Mechon-Mamre. Mechon-mamre.org. Retrieved on 2011-02-02.

- ^ a b Alison Futrell (November 2000). Blood in the Arena: The Spectacle of Roman Power. University of Texas Press. p. 177. ISBN 9780292725232. http://books.google.com/books?id=vn3bIZqKB4AC&pg=PA177. Retrieved 29 January 2011.

- ^ Египет: история и современность. Достопримечательности Египта. E-gipet.ru. Retrieved on 2011-02-02.

- ^ Глава II. Гарама: возникновение и расцвет|Гарама|Древняя Ливия|Реконструкция. Rec.gerodot.ru. Retrieved on 2011-02-02.

- ^ Diodorus Siculus.XX Historical Library 14, 4; XXIII 13

- ^ Joyce E. Salisbury (1997). Perpetua's passion: the death and memory of a young Roman woman. Routledge. p. 51. ISBN 9780415918374. http://books.google.com/books?id=JNSoyJBFgXEC&pg=PA51. Retrieved 29 January 2011.

- ^ Frank William Walbank (1989). Rise of Rome to 220 B.C.. Cambridge University Press. p. 514. ISBN 9780521234467. http://books.google.com/books?id=3qXuay2SEtIC&pg=PA514. Retrieved 29 January 2011.

- ^ Гаспаров М.Л. Занимательная Греция. Infoliolib.info. Retrieved on 2011-02-02.

- ^ Polybius. General History of I 82, 2

- ^ a b Pliny the Elder. Natural history. VIII, Sec. VII.

- ^ a b Тираспольский Г. И. Беседы с палачом. Казни, пытки и суровые наказания в Древнем Риме (Conversations with an executioner. Executions, torture and harsh punishment in ancient Rome). Moscow, 2003. (in Russian)

- ^ Библиотека. Invictory.org. Retrieved on 2011-02-02.

- ^ Гладиаторы. 4ygeca.com. Retrieved on 2011-02-02.

- ^ Venatio I

- ^ Livy. History of Rome from the founding of the city XXXIX 22, 2

- ^ a b c d Мария Ефимовна Сергеенко. Krotov.info. Retrieved on 2011-02-02.

- ^ Livy. Epitoma. "History of Rome from the founding of the city"

- ^ Совершение казни с помощью хищников. » Белая Калитва. Kalitva.ru. Retrieved on 2011-02-02.

- ^ Strabo, VI, II, 6

- ^ MARTIALIS.NET, М. Валерий Марциал. Martialis.net. Retrieved on 2011-02-02.

- ^ Cicero. Letters. Vol. 3. p. 461. Letter (Ad) Fam., VII, 1. (DCCCXCV, 3)

- ^ Cicero. Letters. Vol. 1. p. 258. Letter (Ad) Fam., VII, 1. (CXXVII, 3)

- ^ Suetonius. Lives of the Twelve Caesars. p. 118 (IV Gaius Caligula, 27, 1)

- ^ Dio Cassius. Roman history XXXIX in 1938, 2.

- ^ Plutarch. Pompey, 52.

- ^ Pliny the Elder. Natural History VIII, 64

- ^ Pliny the Elder. Natural history. VIII, 53.

- ^ Cod. Theod. XV; tit. XI. 1–2.

- ^ Немировский. История древнего мира. (The history of the ancient world) Ch. 1. p. 86 // Тираспольский Г. И. Беседы с палачом (Conversations with an executioner)

- ^ Tacitus. Annals, XV, 44

- ^ Murders. Murders.ru. Retrieved on 2011-02-02.

- ^ a b Гонения на христиан в Римской империи. Ateismy.net. Retrieved on 2011-02-02.

- ^ The Genealogy of Jesus Christ

- ^ Болотов В.В. Лекции по истории древней Церкви с конца I по начало IV вв (1). Rodon.org. Retrieved on 2011-02-02.

- ^ О прескрипции против еретиков

- ^ a b c d e The Civil Law, sps11

- ^ Волхвы (Volkhvy) (in Russian)

- ^ a b The Civil Law, sps15

- ^ (истории). www.diet.ru. Retrieved on 2011-02-02.

- ^ ГЛАВА 1. ИСТОРИЯ И ПРЕДПОСЫЛКИ ВОЗНИКНОВЕНИЯ ФАЛЬШИВОМОНЕТНИЧЕСТВА // Право России //. Allpravo.ru. Retrieved on 2011-02-02. (in Russian)

- ^ VI: Светлейший муж Вулкаций Галликан. АВИДИЙ КАССИЙ, Властелины Рима. Биографии римских императоров от Адриана до Диоклетиана. Krotov.info. Retrieved on 2011-02-02.

- ^ XXVI: Флавий Вописк Сиракузянин. БОЖЕСТВЕННЫЙ АВРЕЛИАН, Властелины Рима. Биографии римских императоров от Адриана до Диоклетиана. Krotov.info. Retrieved on 2011-02-02.

- ^ V. G. Grafsky. General History of Law and State (in Russian)

- ^ The Civil Law, sps6

- ^ Digests of Justinian. Vol. 7-2. Moscow 2005. p. 191, fragment 29

- ^ Digests of Justinian. Vol. 7-2. Moscow 2005. p. 191, fragment 31

- ^ История Византии. Том 2 (Сборник). Historic.ru (2005-06-02). Retrieved on 2011-02-02.

- ^ Saaremaa Muuseum. Saaremaamuuseum.ee. Retrieved on 2011-02-02.

- ^ Frank Northen Magill; Christina J. Moose; Alison Aves (March 1998). Dictionary of World Biography: The ancient world. Taylor & Francis. pp. 587–. ISBN 9780893563134. http://books.google.com/books?id=wyKaVFZqbdUC&pg=PA587. Retrieved 2 February 2011.

- ^ St. Glyceria, Virginmartyr, at Heraclea|Antiochian Orthodox Christian Archdiocese. Antiochian.org. Retrieved on 2011-02-02.

- ^ Aulus Gellius (2nd century), Attic Nights, Vol. 14

- ^ Опюбнякюбмше Пюяяйюгш. Pravoslavie-story.narod.ru. Retrieved on 2011-02-02.

- ^ В логове львов (In the Lions’ Den). Chassidus.ru (2010-07-04). Retrieved on 2011-02-02.

- ^ Литература|Ульвдалир. Эпоха викингов, история Скандинавии. Ulfdalir.ulver.com. Retrieved on 2011-02-02.

- ^ Властелины Рима. Krotov.info. Retrieved on 2011-02-02.

- ^ казни египетские. Электронная еврейская энциклопедия. Eleven.co.il (2006-07-04). Retrieved on 2011-02-02.

- ^ Горы Кавказа (in Russian)

- ^ Игумен Марк (Лозинский) «Отечник проповедника» (in Russian)

- ^ ГОРОД СОЛНЦА Томмазо Кампанелла. Krotov.info. Retrieved on 2011-02-02.

Bibliography

- Scott, S. P. (1932). The Civil Law, including The Twelve Tables, The Institutes of Gaius, The Rules of Ulpian, The Opinions of Paulus, The Enactments of Justinian, and The Constitutions of Leo.. Central Trust Company. http://www.constitution.org/sps/sps.htm.

Further reading

- Donald G. Kyle. (1998). Spectacles of Death in Ancient Rome. ISBN 0415096782.

- Katherine E. Welch. The Roman Amphitheatre. From its Origins to the Colosseum. ISBN 9780521809443.

- Boris A. Paschke (2006). "The Roman ad bestias Execution as a Possible Historical Background for 1 Peter 5.8". Journal for the Study of the New Testament 28 (4): 489–500.

Categories:- Ancient Roman culture

- Gladiatorial combat

- Execution methods

- Latin words and phrases

- Offenders of their Majesty (majestatis rei)

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.