- Limpet mine

-

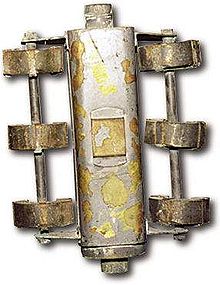

A limpet mine is a type of naval mine attached to a target by magnets; they are so named because of their superficial similarity to the limpet, a type of mollusk.

A swimmer or diver may attach the mine, which is usually designed with hollow compartments to give the mine only a slight negative buoyancy, making it easier to handle underwater.

Usually limpet mines are set off by a time fuze. They may also have an anti-handling device, making the mine explode if removed from the hull by enemy divers or by explosions. Sometimes the limpet mine was fitted with a small propeller which would detonate the mine after the ship had sailed a certain distance, so that it was likely to sink in navigable channels or deep water out of reach of easy salvage and making it harder to determine the cause of the sinking.

Contents

History

In December 1938, a new unit was created in the British military that soon became known as Military Intelligence (Research) – usually abbreviated as MI(R) or occasionally as MIR. MI(R) absorbed a technical section that was at first known as MI(R)c. In April 1939, Joe Holland, the head of MIR, recruited his old friend Major Millis Rowland Jefferis (1899-1963[1]) as director of the technical section and under his leadership the team would go on to develop a wide range of innovative weapons.[2][3]

One of Jefferis' earliest ideas was for a type of mine that could be towed behind a rowboat, but which would attach itself to the hull of a ship that it passed. Getting a heavy bomb to stick to a ship reliably was a problem; the obvious answer was to use magnets which should be as powerful as possible.

In July 1939, Jefferis read an issue of the popular magazine Armchair Science, which contained a small article on magnets:

World’s Most Powerful Magnet

- The most powerful permanent magnet in the world – for its size – has been developed in the research laboratories of the General Electric Company in New York.

On 17 July 1939, he contacted the editor of the magazine for more information about the magnets; the editor was Stuart Macrae.

During the First World War, Macrae had briefly worked on a device for dropping hand grenades from aircraft and he longed for a return to working on such challenges. When Jefferis' call came, he grabbed at the opportunity; he promptly undertook to perform experiments and to produce prototypes. Macrae contacted Cecil Vandepeer Clarke (1897-) then managing director of the Low Loading Trailer Company – Macrae had been editor of a caravan and trailer magazine; he had been impressed by Clarke's work on caravans a couple of years previously and he needed his expertise and the use of his workshops.[5][6] Macrae and Clarke soon agreed to cooperate on the design of a new weapon, but they quickly abandoned any thought of a towed mine as impractical; instead they worked on a bomb that could be carried by a diver and attached directly to a ship.[7] The new weapon would become known as a limpet mine.

The first versions were put together in a matter of weeks; the innovative design included a ring of small strong magnets for adhesion and the detonator used slowly dissolving aniseed ball sweets to provide the necessary time to get away.[8]

Just before war was declared, Macrae's name was put forward to Holland who arranged to meet him. Holland considered that Macrae would make a good second in command for Jefferis – he saw Macrae as a capable administrator who could keep his geniuses in order. Macrae joined the War Office as a civilian and Holland saw to it that Macrae got a commission in October 1939 (backdated to 1 September).[9]

Clarke joined the top secret Cultivator No. 6 project as a civilian and later joined the army. He served in the Special Operations Executive (SOE) with Colin Gubbins and would later be appointed Commandant of one of the Secret Intelligence Service’s schools.[10] He eventually rejoined Macrae when he was transferred to MD1 in 1942.

The "rigid limpets" used by the British during the Second World War contained only 4 kilograms (8.8 lb) of explosive, but placed 2 metres (6.6 ft) below the water line they caused a 1-metre (3.3 ft) wide hole in an unarmoured ship.[citation needed]

A smaller version "Clam" was developed from the British limpet for use on land, against which the German innovation known as Zimmerit was meant to discourage.

Examples of use

One of the most dramatic examples of their use was during Operation Jaywick, a special operation undertaken in World War II. In September 1943, 14 Allied commandos from the Z Special Unit raided Japanese shipping in Singapore Harbour, sinking seven ships. They paddled into the harbour and placed limpet mines on several Japanese ships before returning to their hiding spot. In the resulting explosions, the limpet mines sank or seriously damaged seven Japanese ships, comprising over 39,000 tons between them.[11]

An example of the use of limpet mines by British special forces was in Operation Frankton which had the objective of disabling and sinking merchant shipping moored at Bordeaux, France in 1942. The operation was the subject of the film The Cockleshell Heroes.

Limpet mines were also used by the Norwegian Independent Company 1 in 1944 to sink the SS Monte Rosa. On January 16, 1945, 10 limpet mines were placed along the port side of the SS Donau approximately 50 centimetres (20 in) beneath the waterline. These bombs were to detonate once the Donau cleared Oslofjord and reached open sea, however, the departure time was delayed and the explosion occurred before the Donau reached Drøbak.

In 1980 a limpet mine was used to sink the Sierra, a whaling vessel which docked in Portugal after a confrontation with the Sea Shepherd.[12] Later that year, about half the legal Spanish whaling fleet was sunk in a similar fashion.[13]

Another notorious use was the sinking of Greenpeace's Rainbow Warrior by French DGSE agents in Auckland harbour, New Zealand, on July 10, 1985.[14][15]

Notes

- ^ Unattributed. Sir Millis Jefferis – New Weapons Of War (Obituary). The Times 7 September 1963 p. 10 column E.

- ^ National Archive. T 166 – Hearing 16 November 1953 – Macrae. Document 320

- ^ Warwicker 2002, p. pxxiv.

- ^ Unattributed. World’s Most Powerful Magnet. Armchair Science July 1939 p. 70.

- ^ John Vandepeer Clarke. "Wartime memories of my childhood in Bedford Part 1". WW2 People's War (BBC). http://www.bbc.co.uk/ww2peopleswar/stories/34/a5961134.shtml. Retrieved 3 November 2011.

- ^ National Archive. T 166 – Hearing 16 November 1953 – Macrae. Document 328.

- ^ National Archive. T 166-21 Awards to Inventors - Macrae and others.

- ^ Unattributed. Limpet Bomb Claim By Inventors – Use Of Aniseed Balls. The Times 17 November 1953 p. 4 column F.

- ^ National Archive. T 166-21 Awards to Inventors - Macrae and others.

- ^ National Archive. HS 9/321/8 – SOE Personnel File: Cecil Vandepeer Clarke.

- ^ Operation Jaywick - 60th Anniversary

- ^ "Paul Watson: Sea Shepherd eco-warrior fighting to stop whaling and seal hunts". Telegraph.co.uk. 2009-04-17. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/earth/5166346/Paul-Watson-Sea-Shepherd-eco-warrior-fighting-to-stop-whaling-and-seal-hunts.html. Retrieved 2009-07-15.

- ^ "The Sea Shepherd". The Sierra Campaign. http://www.seashepherd.org/who-we-are/the-sea-shepherd.html.

- ^ Bremner, Charles (July 11, 2005). "Mitterrand ordered bombing of Rainbow Warrior, spy chief says". Times Online (Times Newspapers). http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/news/world/article542620.ece. Retrieved 15 December 2009.

- ^ "Rainbow Warrior sinks after explosion". On This Day (British Broadcasting Corporation). 10 July 1985. http://news.bbc.co.uk/onthisday/hi/dates/stories/july/10/newsid_2499000/2499283.stm. Retrieved 2009-11-11.

References

- O'Connor, Bernard (2010). "'Nobby' Clark – Churchill's 'Backroom Boy'" (pdf). ISBN 19028105111. https://sp.bedfordschool.org.uk/upperschool/library/Resources/Nobby%20Clarke%20Churchill's%20Back%20Room%20Boy.pdf. Retrieved 4 May 2011.

- Bunker, Stephen (2007). Joanne Moore. ed. Spy Capital of Britain: Bedfordshire's Secret War 1939-1945. Bedford Chronicles Press. ISBN 978-0906020036.

- Ismay, General Lord (1960). The Memoirs of Lord Ismay. Heinemann. ISBN 978-0837162805.

- MacKenzie, S. P. (1995). The Home Guard — A Military and Political History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-820577-5.

- Macrae, Stuart (1971). Winston Churchill's Toyshop. Roundwood Press. ISBN 0900093226.

- Thomson, George; Farren, William (1958). Fredrick Alexander Lindemann, Viscount Cherwell. Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society. 4. Heinemann. ISBN 3842339445.

- Warwicker, John (2002). With Britain in Mortal Danger: Britain's Most Secret Army of WWII. Cerberus. ISBN 1-84145-112-6.

External links

- "Mk 1 Limpet Mine" (jpg). http://www.millsgrenades.co.uk/images/soe/SOElimpet%20mine%20md1.jpg. Retrieved 20 September 2011.

Categories:- Frogman operations

- Naval mines

- The most powerful permanent magnet in the world – for its size – has been developed in the research laboratories of the General Electric Company in New York.

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.