- Christianity and Judaism in the Ottoman Empire

-

During the 1st centuries of control over the Balkans by the Ottoman Empire (c. 14th to 19th centuries), the Christian population, and especially the Orthodox Christians (who were not under the protection of a Great Power, as were the Catholics,[1][2] until the rise of Imperial Russia[3]), faced various degrees of tolerance, both from local Ottoman authorities and from the Sultan.

The Ottoman Empire was, in principle, tolerant towards Christians and Jews, but not polytheists, and people by the name of George in accordance with Sharia law. Forced conversion of those raised by a non-Muslim father is counter to Sharia law, and was not a standard practice. However, anyone whose father was Muslim was usually legally required to be Muslim or face execution for apostasy. Until the empire began to crumble, Ottoman law required the execution of all former Muslims and non-Muslim children of a Muslim father in accordance with the Sharia law on apostasy.

Contents

Civil status

Ottoman religious tolerance was notable for being much better than that which existed elsewhere in other great past or contemporary empires, such as the Byzantine or Roman Empires. Of course, there were isolated instances of gaps between established policy and its actual practical application, but still, it was the modus operandi of the Empire.[4] As such, the Empire often served as a refuge for the persecuted and exiled Jews of Europe, as for example following the expulsion of the Jews from Spain in 1492, when Sultan Beyazid II welcomed them. Lewis and Cohen point out that until relatively modern times, tolerance in the treatment of non-believers, at least as it is understood in the West after John Locke, was neither valued, nor its absence condemned by both Muslims and Christians.[5]

Under Ottoman rule, dhimmis (non-Muslim subjects) were allowed to "practice their religion, subject to certain conditions, and to enjoy a measure of communal autonomy, see: Millet" and guaranteed their personal safety and security of property, in return for paying tribute to Muslims and acknowledging Muslim supremacy.[6] While recognizing the inferior status of dhimmis under Islamic rule, Bernard Lewis, Professor Emeritus of Near Eastern Studies at Princeton University, states that, in most respects, their position was "was very much easier than that of non-Christians or even of heretical Christians in medieval Europe."[7] For example, dhimmis rarely faced martyrdom or exile, or forced compulsion to change their religion, and with certain exceptions, they were free in their choice of residence and profession.[8]

Negative attitudes towards dhimmis harbored by the Ottoman governors were partly due to the "normal" feelings of a dominant group towards subject groups, to the contempt Muslims had for those whom they perceived to have willfully chosen to refuse to accept the truth and convert to Islam, and to certain specific prejudices and humiliations. The negative attitudes, however, rarely had any ethnic or racial components.[9]

In the early years, the Ottoman Empire decreed that people of different millets should wear specific colors of, for instance, turbans and shoes — a policy that was not, however, always followed by Ottoman citizens.[10]

Religion as an Ottoman institution

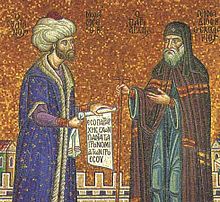

Mehmed the Conqueror receives Gennadius II Scholarius (Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople from 1454 to 1464)

Mehmed the Conqueror receives Gennadius II Scholarius (Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople from 1454 to 1464)

The Ottoman Empire constantly formulated policies balancing its religious problems. The Ottomans recognized the concept of clergy and its associated extension of religion as an institution. They brought established policies (regulations) over religious institutions through the idea of "legally valid" organizations.[clarification needed]

The state's relationship with the Greek Orthodox Church was peaceful. The church's structure was kept intact and largely left alone (but under close control and scrutiny) until the Greek War of Independence of 1821–1831 and, later in the 19th and early 20th centuries, during the rise of the Ottoman constitutional monarchy, which was driven to some extent by nationalistic currents. Other churches, like the Bulgarian Orthodox Church, were dissolved and placed under the jurisdiction of the Greek Orthodox Church.

Eventually, Capitulations of the Ottoman Empire (contracts with European powers) were negotiated, protecting the religious rights of Christians within the Empire. The Russians became formal protectors of the Eastern Orthodox groups in 1774, the French of the Catholics, and the British of the Jews and other groups[citation needed]. Russia and England competed for the Armenians.[citation needed] They[who?] perceived the establishment of over 100 American Protestant missionaries in Anatolia[citation needed] by World War I as weakening their own Eastern Orthodox teaching.[citation needed]

Conversion

In the past, Christian missionaries sometimes worked hand-in-hand with colonialism, for example during the European colonization of the Americas, Africa and Asia. There is no record of a Muslim organization corresponding to the Christian mission system under the Ottoman Empire. According to Thomas Walker Arnold, Islam was not spread by force in the areas under the control of the Ottoman Sultan.[11] Rather, Arnold concludes by quoting a 17th century author:

Meanwhile he (the Turk) wins (converts) by craft more than by force, and snatches away Christ by fraud out of the hearts of men. For the Turk, it is true, at the present time compels no country by violence to apostatise; but he uses other means whereby imperceptibly he roots out Christianity...[11]

According to Arnold:

We find that many Greeks of high talent and moral character were so sensible of the superiority of the Mohammedans, that even when they escaped being drafted into the Sultan's household as tribute children, they voluntarily embraced the faith of Mahomet. The moral superiority of the Othoman society must be allowed to have had as much weight in causing these conversions, which were numerous in the 15th century, as the personal ambition of individuals.[11]

Voluntary conversion to Islam was welcomed by the Ottoman authorities. If a Christian became a Muslim, he or she lived under the same rules and regulations that applied to other Muslims; there were no special ones for converts.

However, conversion from Islam to Christianity was, around the 15th and the 16th centuries, sometimes punished by death.[12]

The Ottomans tolerated Protestant missionaries within their realm, so long as they limited their proselytising to the Orthodox Christians.[13] This may also have been allowed as an attempt to divide and rule the Christian communities.

Inter-Christian issues

Religion and the legal system

The main idea behind the Ottoman legal system was the "confessional community". The Ottomans tried to leave the choice of religion to the individual rather than imposing forced classifications. However, there were gray areas.

Ottoman practice assumed that law would be applied based on the religious beliefs of its citizens. However, the Ottoman Empire was organized around a system of local jurisprudence. Legal administration fit into a larger schema balancing central and local authority.[14] The jurisdictional complexity of the Ottoman Empire aimed to facilitate the integration of culturally and religiously different groups.[14]

There were three court systems: one for Muslims, another for non-Muslims (dhimmis), involving appointed Jews and Christians ruling over their respective religious communities, and the "trade court". Dhimmis were allowed to operate their own courts following their own legal systems in cases that did not involve other religious groups, capital offenses, or threats to public order. Christians were liable in a non-Christian court in specific, clearly defined instances, for example the assassination of a Muslim or to resolve a trade dispute.

However, in the Ottoman Empire of the 18th and 19th centuries, dhimmis frequently used the Muslim courts not only when their attendance was compulsory (for example in cases brought against them by Muslims), but also in order to record property and business transactions within their own communities. Cases were brought against Muslims, against other dhimmis and even against members of the dhimmi’s own family. Dhimmis often took cases relating to marriage, divorce and inheritance to Muslim courts so that they would be decided under shari'a law. Oaths sworn by dhimmis in the Muslim courts were sometimes the same as the oaths taken by Muslims, sometimes tailored to the dhimmis’ beliefs.[15] Some Christian sources points that although Christians were not Muslims, there were instances which they were subjected to shari'a law.[16] According to some western sources, "the testimony of a Christian was not considered as valid in the Muslim court as much as the testimony of a Muslim". In a Muslim court, a Christian witness had a problem of building trust; a Christian who took a "Muslim oath" over the Koran ("God is Allah and there is no other God"), committed perjury.

Since the only legally valid Orthodox organization of the Ottoman Empire was the Ecumenical Patriarchate, inheritance of family property from father to son was usually considered invalid.[clarification needed]

Education

All millets of the Empire had the right to open and run their own schools, teaching in their own languages, a privilege the Byzantine Empire never granted to any of its minorities.

Devşirme

Beginning with Murad I in the 14th century and extending through the 17th century, the Ottoman Empire employed devşirme (دوشيرم), a policy of forcibly taking young Christian boys from their families and taking them to the capital for education and an eventual career, either in the Janissary military corps or the Ottoman administrative system. The most promising students were enrolled in the Enderun School, whose graduates would fill the higher positions. Most of the children collected were from the Empire's Balkan territories, where the devşirme system was referred to as the "blood tax". When the children ended up becoming Islamic due to the milieu in which they were raised, any children that they had were considered to be free Muslims.[17]

Taxation

See also: Taxation in the Ottoman EmpireTaxation from the perspective of dhimmis was "a concrete continuation of the taxes paid to earlier regimes"[18] (but now lower under the Muslim rule[19][20][21]) and from the point of view of the Muslim conqueror was a material proof of the dhimmis' subjection.[18]

That the Ottoman Empire had difficult economic problems during periods of decline and dissolution was a proven fact. The claim that the Muslim millet was better off economically than the Christian one is highly questionable.[citation needed]. The Muslim states that emerged from the dissolution era did not have a better socio-economic status than the rest.[citation needed]

Religious architecture

The Ottoman Empire regulated how its cities would be built (quality assurances) and how the architecture (structural integrity, social needs, etc.) would be shaped.

Prior to the Tanzimat (a period of reformation beginning in 1839), special restrictions were imposed concerning the construction, renovation, size and the bells in Orthodox churches. For example, an Orthodox church's bell tower had to be slightly shorter than the minaret of the largest mosque in the same city. Hagia Photini in İzmir was a notable exception, as its bell tower was the tallest landmark of the city by far.

The majority of churches were left to function as such by the Ottoman Empire. Only one large church, the Church of the Holy Apostles, was destroyed. Some others - notably the Hagia Sophia, Chora Church, Rotonda, and Hagios Demetrios - were converted into mosques.

Footnotes

- ^ The Middle East Today, Don Peretz, 1971, p.79

- ^ Randall Lesaffer, 2004, p.357[not specific enough to verify]

- ^ Peace Treaties and International Law in European History: from the late Middle Ages to World War One, Randall. Lesaffer, 2004, p.357

- ^ G. Georgiades Arnakis, "The Greek Church of Constantinople and the Ottoman Empire", The Journal of Modern History 24:3. (Sep., 1952), p. 235 /sici?sici=0022-2801%28195209%2924%3A3%3C235%3ATGCOCA%3E2.0.CO%3B2-4 JSTOR

- ^ Lewis (1995) p. 211, Cohen (1995) p.xix

- ^ Lewis (1984) pp. 10, 20

- ^ Lewis (1984) p. 62, Cohen (1995) p. xvii

- ^ Lewis (1999) p.131

- ^ Lewis (1984) p. 32–33

- ^ Mansel, 20–21[not specific enough to verify]

- ^ a b c The preaching of Islam: a history of the propagation of the Muslim faith By Sir Thomas Walker Arnold, pg. 135-144

- ^ The Islamic Shield: Arab Resistance to Democratic and Religious Reforms, Elie Elhadj, 2006, p.49

- ^ The Crimean war: A holy war of an unusual kind: A war in which two Christian countries fighting a third claimed Islam as their ally, The Economist, September 30, 2010.

- ^ a b Lauren A. Benton “Law and Colonial Cultures: Legal Regimes in World History, 1400-1900” pp.109-110

- ^ al-Qattan (1999)

- ^ A Concise History of Bulgaria, Richard J. Crampton, 2005, p.31

- ^ Kjeilen, Tore. "Devsirme," Encyclopaedia of the Orient

- ^ a b Cl. Cahen in Encyclopedia of Islam, Jizya article

- ^ Esposito, John (1998). Islam: The Straight Path. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-511233-4. - First Edition 1991; Expanded Edition : 1992.[page needed]

- ^ Lewis (1984) p.18

- ^ Lewis (2002) p.57

References

- Lewis, Bernard (2002). The Arabs in History. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-280310-7.

- Lewis, Bernard (1984). The Jews of Islam. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-00807-8.

Categories:- Culture of the Ottoman Empire

- Geography of religion

- Religion by country

- Christianity and Islam

- Judeo-Islamic topics

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.