- Charles B. Gatewood

-

Charles Bare Gatewood

Nickname Scipio Africanus

"Nanton Bse-che" translated as Big Nose CaptainBorn April 5, 1853

Woodstock, VirginiaDied May 20, 1896 (aged 43)

Fort Monroe, VirginiaPlace of burial Arlington National Cemetery Allegiance  United States of America

United States of AmericaService/branch  United States Army

United States ArmyYears of service 1873 – 1894 Rank First Lieutenant Unit 6th Cavalry Battles/wars Victorio's War

Geronimo's War- Geronimo Campaign

- Battle of Devil's Creek

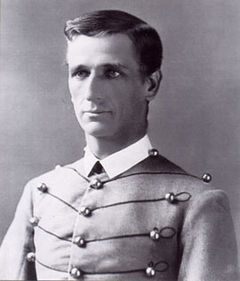

First Lieutenant Charles Bare Gatewood (April 5, 1853 – May 20, 1896) was an American soldier born in Woodstock, Virginia. He served in the United States Army in the 6th Cavalry after graduating from West Point. Upon assignment to the American Southwest, Gatewood led platoons of Apache and Navajo scouts against renegades during the Apache Wars. In 1886 he played a key role in ending the Geronimo Campaign by persuading Geronimo to surrender to the army.[1] Beset with health problems due to exposure in the Southwest and Dakotas, Gatewood was critically injured in the Johnson County War and retired from the Army in 1895, dying a year later from stomach cancer. Before his retirement he was nominated for the Medal of Honor, but was denied the award. He was portrayed by Jason Patric in the 1993 film Geronimo: An American Legend.[2]

Contents

Early life

Gatewood was born into a military family in Woodstock, Virginia, on April 5, 1853. He became a Cadet at the United States Military Academy at West Point in 1873 where he earned the nickname Scipio Africanus because of his resemblance to the Roman general of the same name. He graduated in 1877 with a commission as Second Lieutenant and received orders to the 6th Cavalry in the Southwest at Fort Wingate, New Mexico.[3]

Apache Wars

Gatewood led companies of Apache and Navajo Scouts in Apache territory throughout the Southwestern United States. He was respected among the Apaches and earned the nickname Nanton Bse-che, meaning "Big-nosed Captain". After one year of service at Fort Wingate, Gatewood was made the commander of Apache scouts from the White Mountain Apache Reservation, and later an aide-de-camp to General Nelson Miles. One of his sergeants was a scout who was a former White Mountain Chief named Alchesay.[4]

Gatewood knew his success with the scouts depended on two things: understanding their ways and gaining their acceptance. He accomplished this by meeting with his scouts daily, suppressing any thoughts of racial superiority, and never talking down to them.[5]

Victorio's War

In 1879 Gatewood and his Apache scouts were brought from Arizona to the Black Range Mountains of New Mexico to capture the Apache Chief Victorio in the Victorio Campaign. He and his scouts were placed under the command of Major Albert P. Morrow of the Ninth Cavalry at Fort Bayard, New Mexico. Gatewood's scouts skirmished with Victorio's band, but ultimately failed to capture him.[6]

In May of 1881 he returned to Virginia on sick leave because he had developed rheumatism from exposure to the elements in his two years working with the Apache scouts in the harsh Southwest. He married Georgia McCulloh, the daughter of Thomas G. McCulloh and niece of Richard Sears McCulloh on June 23, 1881 in Cumberland, Maryland. His sick leave expired in July and having not returned to his post, he was declared AWOL. Gatewood returned to the Southwest on September 17, 1881 under the command of Colonel Eugene Asa Carr in his campaign against the Cibecue and White Mountain Apaches.[7]

Geronimo's War

In 1882, the US Army sent Brigadier General George Crook to take command of Indian operations in Arizona Territory. Crook was an experienced Indian fighter who had long since learned that regular soldiers were almost useless against the Apaches and had based his entire strategy on employing "Indians to fight other Indians". The Apache, as a mark of respect, nicknamed Crook Nantan Lupan, which means "Grey Wolf". Despite having subjugated all the major tribes of Apaches in the Territory. The Apaches had once again taken up arms, this time under the leadership of Geronimo. Crook repeatedly saw Geronimo and his band of warriors escape every time.[8]

Knowing Gatewood's reputation as one of the army's "Best Apache Men", Crook made him Commandant of the White Mountain Indian Reservation at Fort Apache under Emmet Crawford. Gatewood and Crook disagreed on handling of the reservation and treatment of the Apaches. After a clash with local politicians over grazing rights on reservation land, Crook had Gatewood transferred in 1885 to command Navajo Scouts. That same year Crook resigned from the Army and Philip Sheridan had him replaced by General Nelson Miles in the Geronimo Campaign.[9]

Although Crook and Gatewood had a falling-out, Gatewood was regarded by Miles as a "Crook Man";[10] despite this and Gatewood's failing health, Miles knew that Gatewood was well known to Geronimo, spoke some Apache, and was familiar with their traditions and values; having spent nearly 10 years in the field with them and against them.[11]

Gatewood was dispatched by General Miles to seek out Geronimo for a parley. On July 21, when he reached Carretas, Chihuahua, Gatewood encountered another Army officer, Lieutenant James Parker of the 4th Cavalry, who had orders to follow Geronimo's trail. Parker told Gatewood, "The trail is all a myth—I haven't seen any trail since three weeks ago when it was washed out by the rains."[12]

Despite his rapidly deteriorating health, Gatewood refused to quit and Parker guided him to Captain Henry Lawton, who was leading a mission to find and kill Geronimo with the Fourth Cavalry. It took two weeks through 150 miles of desertmountain ranges to locate Lawton on the banks of the Aros River on August 3, 1886. Lawton reluctantly allowed Gatewood and his scouts to join his command. Gatewood's health continued to deteriorate. On August 8 he asked Lawron's Surgeon, Leonard Wood, to medically discharge him, but Wood refused.[12] On August 23, 1886, Gatewood led 25 men and two Apache scouts into the Sierra Madre and found Geronimo's camp: his band reduced to 20 men and 14 women and children. On August 24 Gatewood approached Geronimo's camp with only 2 soldiers: George Medhurst Wratten, who was fluent in all Apache dialects and one other; 2 interpreters: Tom Horn and Jesús María Yestes; and two Chiricahua scouts: Kayitah, a Chokonen, and Martine, a Nedni, so as not to alarm the Apaches. Kayitah and Martine made the initial contact, being invited into the camp by the Bavispe River. Kayitah remained in the camp as a hostage while Martine left and returned with Gatewood and 15 pounds of tobacco. After Gatewood made gifts of tobacco, Geronimo teased Gatewood about his thinness and sickly look, Gatewood was then told by Geronimo, "you are always welcome in my camp, and it was always safe for you to come".[13] Gatewood encouraged Geronimo to abandon his fight against the US Army. When asked by Geronimo what Gatewood would do in his situation and to "think like an Apache", Gatewood advised him to "put your trust in Miles".[14]

Agreeing to meet with General Miles, Geronimo's band rode with Gatewood to Lawton's camp in Guadalupe Canyon, the entrance to the United States. Lawton received Geronimo and agreed to allow the Apaches to retain their weapons for defense against nearby Mexican troops. Lawton left for a heliograph station to send word to Miles, leaving Lieutenant Abiel Smith in command. Smith and Wood wanted to disarm the Apaches because they were prisoners-of-war. Smith told Gatewood that he wanted a meeting with Geronimo's men, but Gatewood refused because he knew Smith wanted to murder Geronimo, rather than bring him to Miles. Smith persisted and Gatewood threatened to "blow the head off the first soldier in line", who was Leonard Wood, Wood left to write a dispatch and Gatewood turned to the next man, Smith, who finally relented.[15]

The troops and the Apaches arrived at Skeleton Canyon, Arizona, in the Peloncillo Mountains without incident on September 2, 1886. Miles arrived on September 3, 1886, and Geronimo formerly surrendered for the fourth and final time on September 4. At the conclusion of the surrender, Geronimo turned to Gatewood and said to him, in Apache, "Good. You told the truth". The following day Naiche surrendered, he had been in a nearby canyon mourning his brother, who had been killed by Mexican soldiers, bringing the Apache wars to an official end in the Southwest.[16]

Despite his success, Miles chastised Gatewood for "disobeying orders" as Gatewood made the final approach to Geronimo with only a party of 6 instead of 25. Gatewood reasoned that a larger party would have scared the Apache and made them flee. The city of Tucson, Arizona, held a Gala event to celebrate Geronimo's surrender and invited Gatewood to be the guest of honor, but Miles refused to let him attend. Miles appointed Gatewood as his "Aide-de-Camp", to keep the lieutenant under scrutiny, Miles downplayed Gatewood's role in Geronimo's surrender mostly because it would have given legitimacy to Crook's strategy.[17][18]

Ghost Dance War

In December 1890, Gatewood was reassigned to the Sixth Cavalry, H Troop. His regiment was ordered to South Dakota's Pine Ridge Agency in an operation against hostile Sioux Indians but was not engaged in the final campaign that culminated in the tragedy at Wounded Knee in December. Gatewood developed rheumatism in both shoulders and was unable to move his arms, again due to the cold weather, in January and had medical orders to leave in February 1891 for Hot Springs, South Dakota.[19]

Johnson County War

By September 1891 Gatewood had recovered and he rejoined the Sixth Cavalry, then stationed at Fort McKinney, Wyoming. Wyoming was undergoing a range war between ranchers and farmers that would be known as the Johnson County War and the Sixth Cavalry was dispatched at the request of Acting Governor Amos W. Barber. On May 18, 1892 cowboys from the Red Sash Ranch set fire to the Post exchange and planted a bomb in the form of gunpowder in a barracks stove. Gatewood was responding to the fire and was injured by a bomb blast in a barracks; his left arm was shattered, rendering him too disabled to serve in the Cavalry.[20]

Soon after, The Ninth Cavalry of "Buffalo Soldiers" was ordered to Fort McKinney to replace the Sixth Cavalry.[21]

Death and legacy

On November 19, 1892, Gatewood received orders for Denver, Colorado to await his muster out of the Army. On June 4, 1894, he sought a position as the military advisor of El Paso County, Colorado, to aid in the Cripple Creek miners' strike of 1894 in Cripple Creek, Colorado, but was denied. In 1894 he retired from the Army and moved to Fort Myer, Virginia.[22] In 1895 he was recommended for the Medal of Honor by General Nelson A. Miles, "for gallantry in going alone at the risk of his life into the hostile Apache camp of Geronimo in Sonora, August 24, 1886," but was denied by the acting Secretary of War because Gatewood never distinguished himself in hostile action.[23] In 1896 he suffered excruciating stomach pains and went to a Veteran's Hospital in Fort Monroe, Virginia, for treatment. Gatewood died on May 20, 1896, of stomach cancer and his body was buried at Arlington National Cemetery with full military honors.[24]

On May 23, 1896, Colonel D. S. Gordon, commander of the 6th Cavalry, issued General Order 19, which stated: "It is with extreme sorrow and regret that the Colonel commanding the regiment announced the death of First Lieutenant Charles B. Gatewood at Fort Monroe May 20. Too much cannot be said in honor of this brave officer and it is lamentable that he should have died with only the rank of a Lieutenant, after his brilliant services to the Government. That no material advantages reverted to him is regretted by every officer of his regiment, who extend to his bereaved family their most profound, earnest and sincere sympathy. As a mark of respect to his memory, the officers of the regiment will wear the usual badge of mourning for the period of 30 days."[25]

His son, Charles B. Gatewood, Jr (January 4, 1883 – November 13, 1953), joined the Army and rose to the rank of colonel. He campaigned for recognition of his father's name and later compiled and published his father's memoirs.[26]

Gatewood was portrayed by Jason Patric in the 1993 film Geronimo: An American Legend.[27]

References

- Gatewood, Charles B. (2009). Louis Kraft. ed. LT. Charles Gatewood & His Apache Wars Memoir. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 9780803218840.

- ^ Greene, Jerome A. (2007). Indian War veterans: memories of army life and campaigns in the West, 1864–1898. Casemate Publishers. ISBN 9781932714265.

- ^ Walter Hill (December 10, 1993). Geronimo: An American Legend (film). United States: Columbia Pictures.

- ^ Faulk, Odie B. (1993). The Geronimo campaign. Oxford University Press,. p. 38. ISBN 9780195083514.

- ^ Kraft, Louis (2000). Gatewood & Geronimo. University of New Mexico Press. p. 221. ISBN 9780826321305.

- ^ Gatewood (2009) p. xx

- ^ Chamberlain, Kathleen P. (2007). Victorio: Apache warrior and chief. University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 173–175. ISBN 9780806138435.

- ^ Gatewood (2009) p. xxv

- ^ Kraft(2000) p.34

- ^ Kraft(2000) pp.59–64

- ^ McCallum, Jack Edward (2006). Leonard Wood: Rough Rider, surgeon, architect of American imperialism. NYU Press. p. 40. ISBN 9780814756997.

- ^ Wooster, Robert (1996). Nelson A. Miles and the Twilight of the Frontier Army. University of Nebraska Press. pp. 150–151. ISBN 9780803297753.

- ^ a b Runkle, Benjamin (2011). Wanted Dead Or Alive: Manhunts from Geronimo to Bin Laden. Macmillan. pp. 29–33. ISBN 9780230104853.

- ^ Once They Moved Like The Wind: Cochise, Geronimo, And The Apache Wars. New York: Simon and Schuster. 1994. p. 292. ISBN 9780671885564.

- ^ Capps, Benjamin (1975). The Great Chiefs. Time-Life Education. pp. 240. ISBN 978-0316847858.

- ^ Kraft(2000) pp.185–186

- ^ DeMontravel(1998) p.173

- ^ Wooster (1996) p.156

- ^ Mazzanovich, Anton (1926). Trailing Geronimo: Some hitherto unrecorded incidents bearing upon the outbreak of the White mountain Apaches and Geronimo's band in Arizona and New Mexico. Gem Publishing Co.. p. 236.

- ^ Kraft(2000) p. 215

- ^ Kraft (2000) p. 166

- ^ Schubert, Frank N. "The Suggs Affray: The Black Cavalry in the Johnson County War" The Western Historical Quarterly, Vol. 4, No. 1 (January 1973), pp. 57–68

- ^ Kraft (2000) pp. 218–219

- ^ DeMontravel, Peter R. (1998). A hero to his fighting men: Nelson A. Miles, 1839–1925. Kent State University Press. p. 192. ISBN 9780873385947. http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=KXmeG_jTQygC&pg=PA171&dq=gatewood+geronimo+martine+kayitah&hl=en&ei=9O2jTvTwA9K28QP85e3-BQ&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=2&sqi=2&ved=0CDMQ6AEwAQ#v=onepage&q=gatewood%20geronimo%20martine%20kayitah&f=false.

- ^ Kraft (2000) pp. 266–267

- ^ Faulk (1993) p. 183

- ^ DeMontravel(1998) p.403

- ^ Dixon, Wheeler W. (2000). Film genre 2000: new critical essays: The SUNY series, cultural studies in cinema/video. SUNY Press. p. 221. ISBN 9780791445143.

External links

Categories:- 1853 births

- 1896 deaths

- People from Woodstock, Virginia

- United States Military Academy alumni

- American military personnel of the Indian Wars

- Burials at Arlington National Cemetery

- Deaths from stomach cancer

- Cancer deaths in Virginia

- Geronimo Campaign

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.