- Charlie Hebdo

-

Charlie Hedbo

The paper's offices following the 2011 attack.Type Weekly satirical

news magazineFormat Magazine Founded 1961 Political alignment Left-wing, anarchist Official website charliehebdo.fr Charlie Hebdo (Charlie Weekly) is a French satirical political weekly newspaper, successor of Hara-Kiri, created in 1960. Its editor is cartoonist Charb. Irreverent and stridently non-conformist in tone, the publication has a strongly left-wing, anarchist slant.

In the new Charlie Hebdo, Charb, Gébé and Cabu hold all the responsibilities. Val serves as editor and Gébé as artistic director. Under Val's direction, the journal carries a leftist view. The magazine is published every Wednesday, with special editions issued on an unscheduled basis.

In the early hours of November 2, 2011 — the publication date of a special edition called Charia Hebdo, purporting to have Muhammad as guest editor — its offices were destroyed in a firebombing attack, and its website was hacked and replaced with an image of the Grand Mosque in Mecca and the words "No God but Allah."[1][2]

Contents

History

In 1960, Georges Bernier, and François Cavanna launched a monthly magazine entitled Hara-Kiri. Choron acted as the director of publication and Cavanna as its editor. Eventually Cavanna gathered together a team which included Roland Topor, Fred Othon Aristidès, Jean-Marc Reiser, Georges Wolinski, Georges "Gébé" Blondeaux, and Jean "Cabu" Cabut. After an early reader's letter accused them of being "dumb and nasty" ("bête et méchant"), the phrase became an official slogan for the magazine and made it into everyday language in France.

The publication was banned in 1961, but reappeared in 1966. Certain collaborators did not return along with the newspaper, such as Blondeaux, Cabut, Topor, and Aristidès. New members of the team included Delfeil de Ton, Pierre Fournier, and Bernhard Willem Holtrop.

1969–1981

In 1969, the team decided to produce a weekly publication as well as a monthly magazine. Gébé and Cabu returned. In February 1969, Hara-Kiri Hebdo was launched, and then renamed L'Hebdo Hara-Kiri in May of the same year.

In November 1970, Charles de Gaulle died in his home village of Colombey, ten days before a club fire caused the death of 146. The magazine released a cover spoofing the popular press's coverage of this disaster, headlined "Tragic Ball at Colombey, one dead." As a result, the journal was once more banned, this time by the Minister of the Interior.

In order to side-step the ban, the team decided to change its title, and used Charlie Hebdo. The new name was derived from a monthly comics magazine called Charlie Mensuel (Charlie Monthly), which had been started by Bernier and de Ton in 1968. Charlie took its name from Charlie Brown, the lead character of Peanuts, and was possibly also a nod to Charles de Gaulle.

In December 1981, the publication ceased, owing to a lack of readers.

1992

From a historical standpoint, there is no direct continuity between the Charlie Hebdo of 1992 and that of its earlier years.

In 1991, Gébé, Cabu and others were reunited to work for La Grosse Bertha, a new weekly magazine resembling Charlie created in reaction to the Gulf War and edited by Val. However, the following year, Val clashed with the publisher, who wanted apolitical mischief, and was fired. Gébé and Cabu walked out with him and decided to launch their own paper again. The three called upon Cavanna, de Ton and Wolinski, requesting their help and input. After much searching for a new name, the obvious idea of resurrecting Charlie-Hebdo was agreed on.

The publication of the new Charlie Hebdo began in July 1992. It profited from the notoriety of its namesake, and was treated as a republication of old. The first issue under the new publication sold 100,000 copies.

Choron tried to restart a weekly Hara-Kiri, but its publication was short-lived.

2004

Following the death of Gébé, Val succeeded him as director of the publication, while still holding his position as editor.

2006

Controversy arose over the publication's February 9, 2006 edition. Under the title "Mahomet débordé par les intégristes" ("Muhammad overwhelmed by fundamentalists"), the front page showed a cartoon of a weeping Prophet Muhammad saying "C'est dur d'être aimé par des cons" ("it's hard to be loved by jerks"). The newspaper reprinted the twelve cartoons of the Jyllands-Posten Muhammad cartoons controversy and added some of their own. Compared to a regular circulation of 100,000 sold copies, this edition enjoyed great commercial success. 160,000 copies were sold and another 150,000 were in print later that day.

In response, French President Jacques Chirac condemned "overt provocations" which could inflame passions. "Anything that can hurt the convictions of someone else, in particular religious convictions, should be avoided", Chirac said. The Grand Mosque, the Muslim World League and the Union of French Islamic Organisations (UOIF) sued, claiming the cartoon edition included racist cartoons.[3]

A later edition contained a statement by a group of 12 writers warning against Islamism - Islamic totalitarianism.[4]

2007

The suit by the Grand Mosque and the UOIF reached the courts in February. Publisher Philippe Val contended "It is racist to imagine that they can't understand a joke" but Francis Szpiner, the lawyer for the Grand Mosque, explained the suit: "Two of those caricatures make a link between Muslims and Muslim terrorists. That has a name and it's called racism."[5]

Future president Nicholas Sarkozy sent a letter to be read in court expressing his support for the ancient French tradition of satire.[6] François Bayrou and François Hollande also expressed their support for freedom of expression. The French Council of the Muslim Faith (CFCM) criticized the expression of these sentiments, claiming they were politicizing a court case.[7]

On March 22, 2007 executive editor Philippe Val was acquitted by the court.[8] The court followed the state attorney's reasoning that two of the three cartoons were not an attack on Islam, but on Muslim terrorists, and that the third cartoon with Mohammed with a bomb in his turban should be seen in the context of the magazine in question which attacked religious fundamentalism.

2011

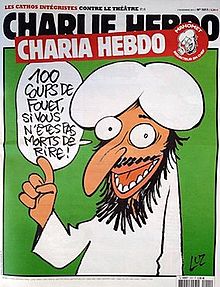

Controversial 2011 issue of Charlie Hebdo renamed "Charia Hebdo". Muhammad is depicted saying, "100 lashes if you are not dying of laughter."

Controversial 2011 issue of Charlie Hebdo renamed "Charia Hebdo". Muhammad is depicted saying, "100 lashes if you are not dying of laughter."

In the early hours of November 2, 2011 the newspaper's office in the 20th arrondissement[9] was fire-bombed and its website hacked. The attack was presumably linked to its decision to rename a special edition "Charia Hebdo", with the Prophet Mohammed listed as the "editor-in-chief".[10]

The editor of Charlie Hebdo, Stéphane Charbonnier ("Charb"),[9] was quoted by AP stating that the attack had been carried out by "stupid people who don't know what Islam is" and that they are "idiots who betray their own religion". Mohammed Moussaoui, head of the French Council of the Muslim Faith, said his organization deplores "the very mocking tone of the paper toward Islam and its prophet but reaffirms with force its total opposition to all acts and all forms of violence."[11] François Fillon, the prime minister, and Claude Guéant, the interior minister, voiced support for Charlie Hebdo.[9]

Others blamed the publication for the attack against it. Time Paris bureau chief Bruce Crumley compared the actions of the publication in writing about Islam to screaming "fire" in a theater.[12] Feminist writer Ayaan Hirsi Ali has criticised these calls for self-censorship.[13]

See also

- Le Canard enchaîné, a satirical weekly French newspaper

References

- ^ "French satirical paper Charlie Hebdo attacked in Paris". BBC News. November 2, 2011. http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-15550350. Retrieved November 03, 2011.

- ^ Geoffroy, Gaelle (November 2, 2011). "Offices of French satirical magazine set on fire after Mohammed issue: editor". Agence France Presse. http://news.nationalpost.com/2011/11/02/offices-of-french-satirical-magazine-set-on-fire-after-mohammed-issue-editor/. Retrieved November 03, 2011.

- ^ http://www.cfcm.tv/2007/03/22/caricatures-charlie-hebdo-relaxe/

- ^ BBC News: Writers' statement on cartoons (March 1 2006)

- ^ Heneghan, Tom, "Cartoon row goes to French court", IOL, February 2 2007 at 06:37pm.

- ^ http://lci.tf1.fr/france/societe/2007-02/soutien-sarkozy-charlie-hebdo-fache-cfcm-4889140.html

- ^ http://www.lexpress.fr/actualite/societe/sarkozy-accuse-de-politiser-le-proces_462776.html

- ^ "French cartoons editor acquitted", BBC, 22 March 2007 14:33 GMT.

- ^ a b c Boxell, James, "Firebomb attack on satirical French magazine", Financial Times, November 2, 2011 12:06 pm. Retrieved 2011-11-02.

- ^ BBC News: Attack on French satirical paper Charlie Hebdo (November 2 2011).

- ^ AP via Google.

- ^ Bruce Crumley. "Firebombed French Paper Is No Free Speech Martyr". Time. http://globalspin.blogs.time.com/2011/11/02/firebombed-french-paper-a-victim-of-islamistsor-its-own-obnoxious-islamophobia/.

- ^ Peter Worthington (9 November 2011). "Extremists hurt non-militant Muslims the most". Toronto Sun. QMI. http://www.torontosun.com/2011/11/09/extremists-hurt-non-militant-muslims-the-most.

Further reading

- La bande à Charlie (Charlie Hebdo). Stock, 1976, by Jean Egen

External links

- Charlie Hebdo (French)

- Un historique d'Hara-Kiri/Charlie Hebdo

- French Satirical Newspaper Charlie Hebdo Wins Second Trial Over Controversial Cartoon Ban Request

- Schofield, Hugh. "Charlie Hebdo and its place in French journalism." BBC. 3 November 2011.

Categories:- Satirical magazines

- Satirical newspapers

- Jyllands-Posten Muhammad cartoons controversy

- Weekly newspapers published in France

- Publications established in 1960

- 1960 establishments in France

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.