- Cryptosporidium

-

This article is about the protozoan. For the disease, see Cryptosporidiosis.

Cryptosporidium

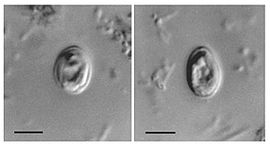

Cryptosporidium muris oocysts found in human feces. Scientific classification Kingdom: Protista Phylum: Apicomplexa Class: Conoidasida Subclass: Coccidiasina Order: Eucoccidiorida Suborder: Eimeriorina Family: Cryptosporidiidae Genus: Cryptosporidium Species Cryptosporidium andersoni

Cryptosporidium bailey

Cryptosporidium canis

Cryptosporidium felis

Cryptosporidium galli

Cryptosporidium hominis

Cryptosporidium meleagridis

Cryptosporidium muris

Cryptosporidium parvum

Cryptosporidium saurophilum

Cryptosporidium serpentis

Cryptosporidium wrairiCryptosporidium is a protozoan that can cause gastro-intestinal illness with diarrhea in humans. Cryptosporidium is the organism most commonly isolated in HIV positive patients presenting with diarrhea. Treatment is symptomatic, with fluid rehydration, electrolyte correction and management of any pain.

Contents

General characteristics

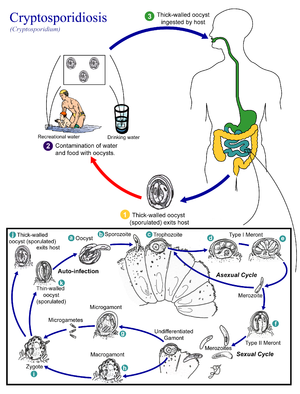

Cryptosporidium is a protozoan pathogen of the Phylum Apicomplexa and causes a diarrheal illness called cryptosporidiosis. Other apicomplexan pathogens include the malaria parasite Plasmodium, and Toxoplasma, the causative agent of toxoplasmosis. Unlike Plasmodium, which transmits via a mosquito vector, Cryptosporidium does not utilize an insect vector and is capable of completing its life cycle within a single host, resulting in cyst stages which are excreted in faeces and are capable of transmission to a new host.

A number of Cryptosporidium infect mammals. In humans, the main causes of disease are C. parvum and C. hominis (previously C. parvum genotype 1). C. canis, C. felis, C. meleagridis, and C. muris can also cause disease in humans.

Cryptosporidiosis is typically an acute short-term infection but can become severe and non-resolving in children and immunocompromised individuals. In humans, it remains in the lower intestine and may remain for up to five weeks.[citation needed] The parasite is transmitted by environmentally hardy cysts (oocysts) that, once ingested, excyst in the small intestine and result in an infection of intestinal epithelial tissue.

The genome of Cryptosporidium parvum was sequenced in 2004 and was found to be unusual amongst Eukaryotes in that the mitochondria seem not to contain DNA.[1] A closely related species, C. hominis, also has its genome sequence available.[2] CryptoDB.org is a NIH-funded database that provides access to the Cryptosporidium genomics data sets.

Life cycle

Cryptosporidium has a spore phase (oocyst) and in this state it can survive for lengthy periods outside a host. It can also resist many common disinfectants, notably chlorine-based disinfectants.[3]

Treatment and Detection

Many treatment plants that take raw water from rivers, lakes, and reservoirs for public drinking water production use conventional filtration technologies. This involves a series of processes including coagulation, flocculation, sedimentation, and filtration. Direct filtration, which is typically used to treat water with low particulate levels, includes coagulation and filtration but not sedimentation. Other common filtration processes including slow sand filters, diatomaceous earth filter and membranes will remove 99% of Cryptosporidium.[4] Membranes and bag and cartridge filters remove Cryptosporidium product-specifically.

Cryptosporidium is highly resistant to chlorine disinfection,[5] however with high enough concentrations and contact time, Cryptosporidium inactivation will occur with chlorine dioxide and ozone treatment. The required levels of chlorine generally preclude the use of chlorine disinfection as a reliable method to control Cryptosporidium in drinking water. Ultraviolet light treatment at relatively low doses will inactivate Cryptosporidium. Water Research Foundation-funded research originally discovered UV's efficacy in inactivating Cryptosporidium.[6][7]

One of the largest challenges in identifying outbreaks is the ability to verify the results within a laboratory environment. Real-time monitoring technology is now able to detect Cryptosporidium with online systems versus the spot testing and batch testing methods used in the past.

For the end consumer of drinking water believed to be contaminated by Cryptosporidium, the safest option is to boil all water used for drinking.[1][2]

Exposure risks

The following groups have an elevated risk of being exposed to Cryptosporidium:[citation needed]

- People who swim regularly in pools with insufficient sanitation (Certain strains of Cryptosporidium are chlorine-resistant)

- Child care workers

- Parents of infected children

- People who take care of other people with cryptosporidiosis

- International travelers

- Backpackers, hikers, and campers who drink unfiltered, untreated water

- People, including swimmers, who swallow water from contaminated sources

- People who handle infected cattle

- People exposed to human feces through sexual contact

Cases of cryptosporidiosis can occur in a city that does not have a contaminated water supply. In a city with clean water, it may be that cases of cryptosporidiosis have different origins. Testing of water, as well as epidemiological study, are necessary to determine the sources of specific infections. Note that Cryptosporidium typically does not cause serious illness in healthy people. It may chronically sicken some children, as well as adults who are exposed and immunocompromised. A subset of the immunocompromised population is people with AIDS. Some sexual behaviours can transmit the parasite directly.

See also

References

- ^ Abrahamsen, M. S.; Templeton, TJ; Enomoto, S; Abrahante, JE; Zhu, G; Lancto, CA; Deng, M; Liu, C et al. (2004). "Complete Genome Sequence of the Apicomplexan, Cryptosporidium parvum". Science (Science/AAAS) 304 (5669): 441–5. doi:10.1126/science.1094786. PMID 15044751.

- ^ Xu, Ping; Widmer, Giovanni; Wang, Yingping; Ozaki, Luiz S.; Alves, Joao M.; Serrano, Myrna G.; Puiu, Daniela; Manque, Patricio et al. (2004). "The genome of Cryptosporidium hominis". Nature 431 (7012): 1107–12. doi:10.1038/nature02977. PMID 15510150.

- ^ "Chlorine Disinfection of Recreational Water for Cryptosporidium parvum". CDC. http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/eid/vol5no4/carpenter.htm. Retrieved 2007-05-06.

- ^ "The Interim Enhanced Surface Water Treatment Rule – What Does it Mean to You?" (pdf). USEPA. http://www.epa.gov/safewater/mdbp/ieswtrwhatdoesitmeantoyou.pdf. Retrieved 2007-05-06.

- ^ Korich, D. G., J. R. Mead, et al. (1990). "Effects of ozone, chlorine dioxide, chlorine, and monochloramine on Cryptosporidium parvum oocyst viability." Appl Environ Microbiol 56(5): 1423-8.

- ^ Rochelle, PAUL A.; Fallar, Daffodil; Marshall, Marilyn M.; Montelone, Beth A.; Upton, Steve J.; Woods, Keith (2004 Sep-October). "Irreversible UV inactivation of Cryptosporidium spp. despite the presence of UV repair genes". J Eukaryot Microbiol 51 (5): 553–62. doi:10.1111/j.1550-7408.2004.tb00291.x. PMID 15537090.

- ^ "Ultraviolet Disinfection and Treatment". WaterResearchFoundation (formerly AwwaRF). http://www.waterresearchfoundation.org/research/TopicsAndProjects/topicSnapshot.aspx?topic=uv. Retrieved 2007-05-06.

- White, A. Clinton, Jr. "Cryptosporidiosis". In Mandell, G et al., eds., Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases, 6th edition; Elsevier, 2005, pp 3215–28.

- Upton, Steve J. (2003-09-12). "Basic Biology of Cryptosporidium" (Website). Kansas State University: Parasitology Laboratory. http://www.k-state.edu/parasitology/basicbio.

- "The Taxonomicon & Systema Naturae" (Website database). Taxon: Genus Cryptosporidium. Universal Taxonomic Services, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. 2000. http://www.taxonomy.nl/taxonomicon/TaxonTree.aspx?id=660.

External links

Categories:

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.