- Military career of George Washington

-

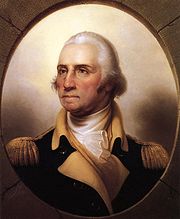

General of the Armies George Washington

Portrait of George Washington in military uniform, painted by Rembrandt Peale.Born February 22, 1732

Westmoreland County, VirginiaDied December 14, 1799 (aged 67)

Mount VernonAllegiance  Great Britain

Great Britain

United States of America

United States of AmericaYears of service 1752–1758

1775–1783

1798–1799Rank  Major 1752–1754

Major 1752–1754

Lieutenant Colonel 1754–1755

Lieutenant Colonel 1754–1755

Colonel 1755–1758

Colonel 1755–1758

Major General[1] 1775–1783

Major General[1] 1775–1783

Lieutenant General 1798–1799

Lieutenant General 1798–1799

General of the Armies of the United States 1976–present (posthumous)Commands held Colonel, Virginia Regiment

General and Commander-in-chief, Continental Army

Commander-in-chief, United States ArmyThe military career of George Washington spanned over forty years of service Washington's service can be broken in three periods (French and Indian War, American Revolutionary War, and the Quasi-War with France) with service in three different armed forces (British provincial militia, the Continental Army, and the United States Army).

Because of Washington's importance in the early history of the United States of America, he was granted a posthumous promotion to General of the Armies of the United States, legislatively defined to be the highest possible rank in the US Army, more than 175 years after his death.

Contents

Background

Born into a well-to-do Virginia family near Fredericksburg in 1732 [O.S. 1731], Washington was schooled locally until the age of 15. The early death of his father when he was 11 eliminated the possibility of schooling in England, and his mother rejected attempts to place him in the Royal Navy.[2] Thanks to the connection by marriage of his half-brother Lawrence to the wealthy Fairfax family, Washington was appointed surveyor of Culpeper County in 1749; he was just 17 years old. Washington's brother had purchased an interest in the Ohio Company, a land acquisition and settlement company whose objective was the settlement of Virginia's frontier areas, including the Ohio Country, territory north and west of the Ohio River.[3] Its investors also included Virginia's Royal Governor, Robert Dinwiddie, who appointed Washington a major in the provincial militia in February 1753.[4][5]

French and Indian War service

Main article: George Washington in the French and Indian WarSee also: Battle of Jumonville Glen, Battle of the Great Meadows, Braddock expedition, and Forbes Expedition Washington's 1754 map showing Ohio River and surrounding region

Washington's 1754 map showing Ohio River and surrounding region

In 1753 the French began expanding their military control into the "Ohio Country", a territory also claimed by the British colonies of Virginia and Pennsylvania. These competing claims led to a world war 1756–63 (called the French and Indian War in the colonies and the Seven Years' War in Europe) and Washington was at the center of its beginning. The Ohio Company was one vehicle through which British investors planned to expand into the territory, opening new settlements and building trading posts for the Indian trade. Governor Dinwiddie received orders from the British government to warn the French of British claims, and sent Major Washington in late 1753 to deliver a letter informing the French of those claims and asking them to leave.[6] Washington also met with Tanacharison (also called "Half-King") and other Iroquois leaders allied to Virginia at Logstown to secure their support in case of conflict with the French; Washington and Half-King became friends and allies. Washington delivered the letter to the local French commander, who politely refused to leave.[7]

Governor Dinwiddie sent Washington back to the Ohio Country to protect an Ohio Company group building a fort at present-day Pittsburg, Pennsylvania. Before he reached the area, a French force drove out the company's crew and began construction of Fort Duquesne. With Mingo allies led by Tanacharison, Washington and some of his militia unit ambushed a French scouting party of some 30 men, led by Joseph Coulon de Jumonville; Jumonville was killed, and there are contradictory accounts of his death.[8] The French responded by attacking and capturing Washington at Fort Necessity in July 1754.[9] He was allowed to return with his troops to Virginia. The episode demonstrated Washington's bravery, initiative, inexperience and impetuosity.[10][11] These events had international consequences; the French accused Washington of assassinating Jumonville, who they claimed was on a diplomatic mission similar to Washington's 1753 mission.[12] Both France and Britain responded by sending troops to North America in 1755, although war was not formally declared until 1756.

Braddock disaster 1755

In 1755, Washington was the senior American aide to British General Edward Braddock on the ill-fated Monongahela expedition. This was at the time the largest ever British military expedition to the colonies, and was intended to expel the French from the Ohio Country. The French and their Indian allies ambushed Braddock, who was mortally wounded in the Battle of the Monongahela. After suffering devastating casualties the British retreated in disarray but Washington rode back and forth across the battlefield, rallying the remnants of the British and Virginian forces to an organized retreat.[13]

Commander of Virginia Regiment

This 1772 painting by Peale of Washington as colonel of the Virginia Regiment, is the earliest known portrait

This 1772 painting by Peale of Washington as colonel of the Virginia Regiment, is the earliest known portrait

Governor Dinwiddie rewarded Washington in 1755 with a commission as "Colonel of the Virginia Regiment and Commander in Chief of all forces now raised in the defense of His Majesty's Colony" and gave him the task of defending Virginia's frontier. The Virginia Regiment was the first full-time American military unit in the colonies (as opposed to part-time militias and the British regular units). Washington was ordered to "act defensively or offensively" as he thought best.[14] In command of a thousand soldiers, Washington was a disciplinarian who emphasized training. He led his men in brutal campaigns against the Indians in the west; in 10 months units of his regiment fought 20 battles, and lost a third of its men. Washington's strenuous efforts meant that Virginia's frontier population suffered less than that of other colonies; Ellis concludes "it was his only unqualified success" in the war.[15][16]

In 1758, Washington participated in the Forbes Expedition to capture Fort Duquesne. He was embarrassed by a friendly fire episode in which his unit and another British unit thought the other was the French enemy and opened fire, with 14 dead and 26 wounded in the mishap. In the end there was no real fighting for the French abandoned the fort and the British scored a major strategic victory, gaining control of the Ohio Valley. Upon his return to Virginia, Washington resigned his commission in December 1758, and did not return to military life until the outbreak of the revolution in 1775.[17]

Although Washington never gained the commission in the British army he yearned for, in these years he gained valuable military, political, and leadership skills,[18] and received significant public exposure in the colonies and abroad.[19][20] He closely observed British military tactics, gaining a keen insight into their strengths and weaknesses that proved invaluable during the Revolution. He demonstrated his toughness and courage in the most difficult situations, including disasters and retreats. He developed a command presence—given his size, strength, stamina, and bravery in battle, he appeared to soldiers to be a natural leader and they followed him without question.[21][22] Washington learned to organize, train, and drill, and discipline his companies and regiments. From his observations, readings and conversations with professional officers, he learned the basics of battlefield tactics, as well as a good understanding of problems of organization and logistics.[23] He developed a very negative idea of the value of militia, who seemed too unreliable, too undisciplined, and too short-term compared to regulars.[24] On the other hand, his experience was limited to command of about 1,000 men, and came only in remote frontier conditions.[25]

American Revolutionary War service

Main article: George Washington in the American RevolutionWashington appeared before the Second Continental Congress in military uniform, signaling that he was prepared for war. Congress created the Continental Army on June 14; the next day it selected Washington as commander-in-chief. There was no serious rival to his experience and confident leadership, let alone his base in the largest colony. Massachusetts delegate John Adams nominated Washington, believing that appointing a southerner to lead what was at this stage primarily an army of northerners would help unite the colonies. Washington reluctantly accepted, declaring "with the utmost sincerity, I do not think myself equal to the Command I [am] honored with."[26] He asked for no pay other than reimbursement of his expenses.

New York and New Jersey

George Washington at Princeton, by Charles Willson Peale, 1779

George Washington at Princeton, by Charles Willson Peale, 1779

George Washington assumed command of the colonial forces in Boston in July 1775, during the ongoing siege of Boston. Realizing his army's desperate shortage of gunpowder, Washington asked for new sources. British arsenals were raided (including some in the West Indies) and some manufacturing was attempted; a barely adequate supply (about 2.5 million pounds) was obtained by the end of 1776, mostly from France.[27]

Washington reorganized the army during the long standoff, and forced the British to withdraw by putting artillery on Dorchester Heights overlooking the city. The British evacuated Boston and Washington moved his army to New York City. In August 1776, British General William Howe launched a massive naval and land campaign to capture New York designed to seize New York City and offer a negotiated settlement. The Americans were committed to independence, but Washington was unable to hold New York. Defeated at the Battle of Long Island on August 22, his army's subsequent nighttime retreat across the East River without the loss of a single life or materiel has been seen by some historians as one of Washington's greatest military feats.[28] Several other defeats sent Washington scrambling across New Jersey, leaving the future of the Continental Army in doubt. On the night of December 25, 1776, Washington staged a counterattack, leading the American forces across the Delaware River to capture nearly 1,000 Hessians in Trenton, New Jersey. Washington followed up the assault with a surprise attack on British forces at Princeton. These unexpected victories after a series of losses recaptured New Jersey, drove the British back to the New York City area, and gave a dramatic boost to Revolutionary morale.

Saratoga and Philadelphia

In 1777, the British launched two uncoordinated attacks. The first was an invasion by General John Burgoyne down the Hudson River from Canada designed to reach New York City and cut off New England. Simultaneously, Howe left New York City and attacked the national capital at Philadelphia. Washington's loss of Philadelphia prompted some members of Congress to discuss removing Washington from command. This episode failed after Washington's supporters rallied behind him.[29]

Washington sent General Horatio Gates and state militias to deal with Burgoyne while he moved the main Continental army south to block Howe's march on Philadelphia. However, Washington's flank was turned at the Battle of Brandywine on September 11, 1777, enabling Howe to march into Philadelphia unopposed. While they occupied the American capital, British forces had become increasingly spread out at this point in the war and Washington saw an opportunity to strike after months of feigned retreats. Thus, Washington's army led a massive attack on the British garrison at the Battle of Germantown in early October. While unsuccessful, the battle left the British army badly scarred and marked the beginning of several offensively-minded moves by Washington. Meanwhile Burgoyne, out of reach from help from Howe, was trapped and forced to surrender his entire army at Saratoga. The British had gained the empty prize of Philadelphia, while losing one of their two armies. The victory caused France to enter the war as an open ally (followed by Spain and the Netherlands as allies of France), turning the Revolution into a major worldwide war in which Britain was no longer the dominant military force.

Washington's army encamped at Valley Forge in December 1777, where it stayed for the next six months. Over the winter, 2,500 men (out of 10,000) died from disease and exposure. The next spring, however, the army emerged from Valley Forge in good order, thanks in part to a full-scale training program supervised by Baron von Steuben, a veteran of the Prussian general staff.

Victory

Depiction by John Trumbull of the surrender of Lord Cornwallis's army at Yorktown

Depiction by John Trumbull of the surrender of Lord Cornwallis's army at Yorktown

French entry into the war changed the dynamics, for the British were no longer sure of command of the seas and had to worry about an invasion of their home islands. The British evacuated Philadelphia in 1778 and returned to New York City, with Washington attacking them along the way at the Battle of Monmouth; this was the last major battle in the north. The British tried a new strategy based on the assumption that most Southerners were Loyalists at heart. Ignoring the north (except for their base in New York), they tried to capture the Southern states while fighting the French elsewhere around the globe. During this time, Washington remained with his army outside New York, looking for an opportunity to strike a decisive blow while dispatching troops to other operations to the north and south. The long-awaited opportunity finally came in 1781, after a French naval victory allowed American and French forces to trap a British army in Virginia. The surrender at Yorktown on October 17, 1781 marked the end of fighting. The Treaty of Paris (1783) recognized the independence of the United States.

Washington's contribution to victory in the American Revolution was not that of a great battlefield tactician; in fact he sometimes planned operations that were too complicated for his amateur soldiers to execute. However, his overall strategy proved to be successful: keep control of 90% of the population at all times; keep the army intact, suppress the Loyalists; and avoid decisive battles except to exploit enemy mistakes (as at Saratoga and Yorktown). Washington was a military conservative: he preferred building a regular army on the European model and fighting a conventional war, and often complained about the undisciplined American militia.

Resignation

Depiction by John Trumbull of Washington resigning his commission and position as commander-in-chief

Depiction by John Trumbull of Washington resigning his commission and position as commander-in-chief

One of Washington's most important contributions as commander-in-chief was to establish the precedent that civilian-elected officials, rather than military officers, possessed ultimate authority over the military. Throughout the war, he deferred to the authority of Congress and state officials, and he relinquished his considerable military power once the fighting was over. In March 1783, Washington used his influence to disperse a group of Army officers who had threatened to confront Congress regarding their back pay. Washington disbanded his army and announced his intent to resign from public life in his "Farewell Orders to the Armies of the United States." The document was written at his final wartime headquarters, a house on the outskirts of Princeton owned by the widow Berrien (later to be called Rockingham), but was sent to be read to the assembled troops at the fort of West Point on November 2.[30] A few days later, the British evacuated New York City, and Washington and the governor took possession of the city; at Fraunces Tavern in the city on December 4, he formally bade his officers farewell. On December 23, 1783, Washington resigned his commission as commander-in-chief to the Congress of the Confederation.

Quasi-War service

Main article: Quasi-WarIn the fall of 1798, Washington was immersed in the business of creating a military force to deal with the threat of an all-out war with France. A clash over Alexander Hamilton's rank in the army led Washington to contemplate resignation of his own post as commander in chief of the army, and the resolution of this affair brought no opportunity for rest as Washington engaged in the tedious task of finding officers for the new military formations. In the spring of 1799, the relaxation of tensions between France and the United States allowed Washington to redirect his attention to his personal affairs.

Posthumous promotion

George Washington died on December 14, 1799, at the age of 67. Upon his passing he was listed as a retired lieutenant general on the rolls of the US Army. Over the next 177 years, various officers surpassed Washington in rank, including most notably John J. Pershing, who was promoted to General of the Armies for his role in World War I. On January 19, 1976, Washington was posthumously promoted to the same rank by congressional joint resolution. The resolution stated that Washington's seniority had rank and precedence over all other grades of the Army, past or present, effectively making Washington the highest ranked U.S. officer of all time.[1]

Battle record

George Washington lost more battles than he won during the American Revolution. During the nine major battles that Washington had field command in, 6 were British victories: Long Island, Kip's Bay, Fort Washington, Brandywine, White Plains and Germantown. Three were American victories: Harlem Heights, Trenton and Princeton. Monmouth was a draw while White Marsh never developed beyond skirmishing. However, his sieges of Boston and Yorktown were victories.[31] Also, under Washington's command, the Americans and French suffered only 8,300 casualties while the British and Hessians suffered 13,800 casualties.[32]

Battles

During his military career, he fought in many battles, mostly in the American Revolution. This is a list of battles in which he held field command. They are listed either under victory or defeat.

Victories

- Jumonville Glen (1754)

- Boston (1775)

- Harlem (1776)

- Trenton (1776)

- Assunpink Creek (1777)

- Princeton (1777)

- Yorktown (1781)

Defeats

- Great Meadows (1754)

- New York (1776)

- Kip's Bay (1776)

- White Plains (1776)

- Fort Washington (1776)

- Brandywine (1777)

- Germantown (1777)

Draw

- Battle of Monmouth (1778)

Rank History

Rank Organization Date Major Province of Virginia militia 1753 Lieutenant Colonel Virginia Regiment 1754 Colonel Virginia Regiment 1755  Major General (General and Commander-in-Chief)

Major General (General and Commander-in-Chief)Continental Army June 1775  Lieutenant General

Lieutenant GeneralUnited States Army 1798  General of the Armies of the United States (posthumous)

General of the Armies of the United States (posthumous)United States Army July 4, 1976 Notes

- ^ a b Bell, William Gardner; COMMANDING GENERALS AND CHIEFS OF STAFF: 1775–2005; Portraits & Biographical Sketches of the United States Army's Senior Officer: 1983, CENTER OF MILITARY HISTORY; UNITED STATES ARMY; WASHINGTON, D.C.: ISBN 0-16-072376-0 : pp 52 & 66

- ^ Freeman, pp. 1:1–199

- ^ Chernow, ch. 1

- ^ Anderson, p. 30

- ^ Freeman, p. 1:268

- ^ Freeman, George Washington (1948), pp. 1:274–327

- ^ Lengel, General George Washington (2005) pp 23–24

- ^ Lengel, General George Washington (2005) pp 31–38

- ^ Grizzard, George Washington pp 115–19

- ^ Ellis, His Excellency: George Washington (2004), pp. 17–18

- ^ The governor promised land bounties to the soldiers and officers who volunteered in 1754; Virginia finally made good on the promise in the early 1770s, with Washington receiving title to 23,200 acres near where the Kanawha River flows into the Ohio River, in what is now western West Virginia. Grizzard, George Washington pp 135–37

- ^ Ellis, His Excellency: George Washington (2004), p. 14

- ^ Ellis, His Excellency: George Washington (2004), p. 22

- ^ Flexner, George Washington: the Forge of Experience, 1732–1775 (1965), p. 138

- ^ Fischer, Washington's Crossing (2004), pp. 15–16

- ^ Ellis, His Excellency: George Washington (2004), p. 38

- ^ Lengel, General George Washington pp 75–76, 81

- ^ Chernow, ch. 8; Freeman and Harwell, pp. 135–139; Flexner (1984), pp. 32–36; Ellis, ch. 1; Higginbotham (1985), ch. 1

- ^ Ellis, p. 14

- ^ O'Meara, p. 45

- ^ Ellis, pp. 38,69

- ^ Fischer, p. 13

- ^ Higginbotham (1985), pp. 14–15

- ^ Higginbotham (1985), pp. 22–25

- ^ Freeman and Harwell, pp. 136–137

- ^ Ellis, p. 70.

- ^ Orlando W. Stephenson, "The Supply of Gunpowder in 1776", American Historical Review, Vol. 30, No. 2 (Jan., 1925), pp. 271-281 in JSTOR

- ^ McCullough, David (2005). 1776. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0743226714.

- ^ Fleming, T: "Washington's Secret War: the Hidden History of Valley Forge.", Smithsonian Books, 2005

- ^ George Washington Papers at the Library of Congress, 1741-1799: Series 3b Varick Transcripts. Library of Congress. Accessed on May 22, 2006.

- ^ Brooks, How America Fought Its Wars: Military Strategy From The American Revolution, pg.157

- ^ Brooks, How America Fought Its Wars: Military Strategy From The American Revolution, pg.158

Sources

- Chernow, Ron (2010). Washington: A Life. New York: Penguin. ISBN 9781594202667. OCLC 535490473.

- Ellis, Joseph J. His Excellency: George Washington. (2004) ISBN 1-4000-4031-0. Acclaimed interpretation of Washington's career.

- Ferling, John E. The First of Men: A Life of George Washington (1989). Biography from a leading scholar.

- Fischer, David Hackett. Washington's Crossing. (2004), prize-winning military history focused on 1776–1777.

- Flexner, James Thomas. Washington: The Indispensable Man. (1974). ISBN 0-316-28616-8 (1994 reissue). Single-volume condensation of Flexner's popular four-volume biography.

- Freeman, Douglas S (1948–1957). George Washington: A Biography. New York: Scribner. OCLC 425613. Seven volumes scholarly biography, winner of the Pulitzer Prize.

- Grizzard, Frank E., Jr. George Washington: A Biographical Companion. ABC-CLIO, 2002. 436 pp. Comprehensive encyclopedia; Grizzard was Senior Associate Editor of The Papers of George Washington

- Commanding Generals and Chiefs of Staff (Center of Military History)

- Marshall, John. The life of George Washington Vol I,II,III & IV.

- Jerry D. Morelock (2002). "Washington as Strategist". Compound Warfare. DIANE Publishing. pp. 53–89. ISBN 9781428910904. http://books.google.com/books?id=q54NDbdVmJMC&pg=PA69&lpg=PA69&dq=lafayette+duel+carlisle&source=bl&ots=dRlx7hkLn8&sig=cER0rOn9z8oi3fB4u_XvR3JZGNc&hl=en&ei=rn3uSZXEL5PWMLGF_ewP&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=4#PPA53,M1.

George Washington Ancestry and

familyGreat-grandfather: John · Grandfather: Lawrence · Father: Augustine · Mother: Mary Ball · Half-brother: Lawrence · Wife: Martha · Stepson: John Parke Custis · Step-granddaughter: Eleanor Parke Custis Lewis · Step-grandson: George Washington Parke Custis

Life Military career · French and Indian War · Mount Vernon · "Town Destroyer" · American Revolution · PresidencyCharacter Navigation Categories:- George Washington

- Military careers

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.