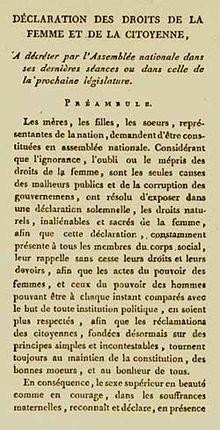

- Declaration of the Rights of Woman and the Female Citizen

-

The Declaration of the Rights of Woman and the Female Citizen (French: Déclaration des droits de la femme et de la citoyenne), also known as the Declaration of the Rights of Woman, was written in 1791 by French activist and playwright Olympe de Gouges. The Declaration is ironic and based on the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, seeking to expose the failure of the French Revolution which had been devoted to gender equality.

Contents

Historical context

The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen was adopted in 1789 by the National Constituent Assembly (Assemblée nationale constituante), during the height of the French Revolution. Prepared and proposed by the marquis de Lafayette, the declaration asserted that all men “are born and remain free and equal in rights” and that these rights were universal. The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen became a key human rights document and a classic formulation of the rights of individuals vis-a-vis the state.[1] The Declaration exposed inconsistencies of laws that treated citizens differently on the basis of sex, race, class or religion.[2] In 1791 new articles were added to the French constitution which extended civil and political rights to Protestants and Jews, who had previously been persecuted in France.[3]

In 1790 Nicolas de Condorcet and Etta Palm d'Aelders unsuccessfully called on the National Assembly to extend civil and political rights to women.[4] Condorcet declared that “and he who votes against the right of another, whatever the religion, color, or sex of that other, has henceforth adjured his own”.[5] The French Revolution did not lead to a recognition of women’s rights and this prompted de Gouges to publish the Declaration of the Rights of Woman and the Female Citizen in September 1791.[6]

The Declaration

The Declaration of the Rights of Woman and the Female Citizen was published in 1791 and is modelled on the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen of 1789. Olympe de Gouges dedicated the text to Marie Antoinette, whom de Gouges described as “the most detested” of women. The Declaration is ironic in formulation and exposes the failure of the French Revolution, which had been devoted to gender equality. It states that:

“This revolution will only take effect when all women become fully aware of their deplorable condition, and of the rights they have lost in society”.

The Declaration of the Rights of Woman and the Female Citizen follows the seventeen articles of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen point for point and has been described by Camille Naish as “almost a parody... of the original document”. The first article of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen proclaims that:

“Men are born and remain free and equal in rights. Social distinctions may be based only on common utility.”

The first article of Declaration of the Rights of Woman and the Female Citizen replied:

“Woman is born free and remains equal to man in rights. Social distinctions may only be based on common utility”.

De Gouges expands the sixth article of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, which declared the rights of citizens to take part in the formation of law, to:

“All citizens including women are equally admissible to all public dignities, offices and employments, according to their capacity, and with no other distinction than that of their virtues and talents”.

De Gouges draws attention to the fact that under French law women were fully punishable, yet denied equal rights, declaring “Women have the right to mount the scaffold, they must also have the right to mount the speaker’s rostrum”.[7]

See also

- The March on Versailles

- Women's Petition to the National Assembly

- Women's rights

References

- ^ Lauren, Paul Gordon (2003). The evolution of international human rights. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 18–20. ISBN 978-0-8122-1854-1. http://books.google.com/books?id=gHRhWgbWyzMC&dq=Declaration+of+the+Rights+of+Man+and+of+the+Citizen&source=gbs_navlinks_s.

- ^ Williams, Helen Maria; Neil Fraistat, Susan Sniader Lanser, David Brookshire (2001). Letters written in France. Broadview Press Ltd. p. 246. ISBN 978-1551112558. http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=5Ruwz82RicgC&dq=Declaration+of+the+Rights+of+Woman+and+the+Female+Citizen&source=gbs_navlinks_s.

- ^ Lauren, Paul Gordon (2003). The evolution of international human rights. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 18–20. ISBN 978-0-8122-1854-1. http://books.google.com/books?id=gHRhWgbWyzMC&dq=Declaration+of+the+Rights+of+Man+and+of+the+Citizen&source=gbs_navlinks_s.

- ^ Williams, Helen Maria; Neil Fraistat, Susan Sniader Lanser, David Brookshire (2001). Letters written in France. Broadview Press Ltd. p. 246. ISBN 978-1551112558. http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=5Ruwz82RicgC&dq=Declaration+of+the+Rights+of+Woman+and+the+Female+Citizen&source=gbs_navlinks_s.

- ^ Lauren, Paul Gordon (2003). The evolution of international human rights. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 18–20. ISBN 978-0-8122-1854-1. http://books.google.com/books?id=gHRhWgbWyzMC&dq=Declaration+of+the+Rights+of+Man+and+of+the+Citizen&source=gbs_navlinks_s.

- ^ Naish, Camille (1991). Death comes to the maiden: Sex and Execution, 1431–1933. Routledge. p. 136. ISBN 978-0415055857. http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=OHYOAAAAQAAJ&dq=Declaration+of+the+Rights+of+Woman+and+the+Female+Citizen&source=gbs_navlinks_s.

- ^ Naish, Camille (1991). Death comes to the maiden: Sex and Execution, 1431–1933. Routledge. p. 137. ISBN 978-0415055857. http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=OHYOAAAAQAAJ&dq=Declaration+of+the+Rights+of+Woman+and+the+Female+Citizen&source=gbs_navlinks_s.

Categories:- 1791 events of the French Revolution

- 1791 works

- Feminism in France

- Feminism and history

- Women's rights

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.