- Codex Amiatinus

-

The Codex Amiatinus, designated by siglum A, is the earliest surviving manuscript of the nearly complete Bible in the Latin Vulgate version,[1] and is considered to be the most accurate copy of St. Jerome's text. It is missing the Book of Baruch. It was produced in the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Northumbria as a gift for the Pope, and dates to the start of the 8th century. The Codex is also a fine specimen of medieval calligraphy, and is now kept at Florence in the Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana (Cat. Sala Studio 6).

Contents

Description

The symbol for it is written am or A (Wordsworth). It is preserved in an immense tome, measuring 19 1/4 inches in height, 13 3/8 inches in breadth, and 7 inches in thickness, and weighs over 75 pounds — so impressive, as Hort says, as to fill the beholder with a feeling akin to awe.[2][3]

It contains Epistula Hieronymi ad Damasum, Prolegomena to the four Gospels.

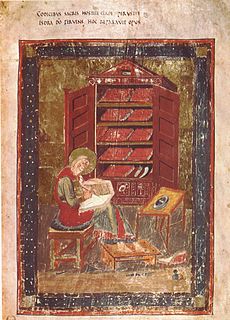

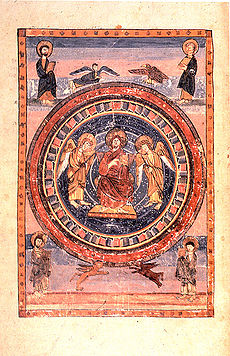

Some consider it, with White, as perhaps "the finest book in the world"; still there are several manuscripts which are as beautifully written and have besides, like the Book of Kells or Lindisfarne Gospels, those exquisite ornaments of which Amiatinus is devoid. It qualifies as an illuminated manuscript as it has some decoration including two full-page miniatures, but these show little sign of the usual insular style of Northumbrian art and are clearly copied from Late Antique originals. It contains 1040 leaves of strong, smooth vellum, fresh-looking today despite their great antiquity, arranged in quires of four sheets, or quaternions. It is written in uncial characters, large, clear, regular, and beautiful, two columns to a page, and 43 or 44 lines to a column. A little space is often left between words, but the writing is in general continuous. The text is divided into sections, which in the Gospels correspond closely to the Ammonian Sections. There are no marks of punctuation, but the skilled reader was guided into the sense by stichometric, or verse-like, arrangement into coda and commata, which correspond roughly to the principal and dependent clauses of a sentence. From this manner of writing the scribe is believed to have been modeled upon the Codex Grandior of Cassiodorus,[4] but it may go back, perhaps, even to St. Jerome.

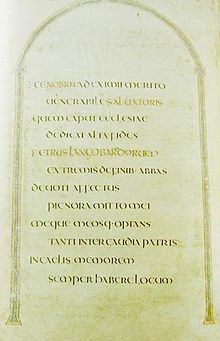

Page with dedication; "Ceolfrith of the English" was altered into "Peter of the Lombards"

Page with dedication; "Ceolfrith of the English" was altered into "Peter of the Lombards"

Originally three copies of the Bible were commissioned by Ceolfrid in 692.[1] This date has been established as the double monastery of Wearmouth-Jarrow secured a grant of additional land to raise the 2000 head of cattle needed to produce the vellum. Bede was most likely involved in the compilation. Ceolfrid accompanied one copy intended as a gift to Pope Gregory II, but he died on route to Rome.[1] The book later appears in the 9th century in Abbey of the Saviour, Monte Amiata in Tuscany (hence the description "Amiatinus"), where it remained until 1786 when it passed to the Laurentian Library in Florence. The dedication page had been altered and the librarian Angelo Maria Bandini suggested that the author was Servandus, a follower of St. Benedict, and was produced at Monte Cassino around the 540s. This claim was accepted for the next hundred years, establishing it as the oldest copy of the Vulgate, but scholars in Germany noted the similarity to 9th c. texts. In 1888 Giovanni Battista de Rossi established that the Codex was related to the Bibles mentioned by Bede. This also established that Amiatinus was related to the Greenleaf Bible fragment in the British Library. Although de Rossi's attribution removed 150 years from the age of the Codex, it remained the oldest version of the Vulgate.

See also

- List of New Testament Latin manuscripts

- Celt (tool) – a famous mistake in most Vulgates, not found in this copy

References

- ^ a b c Bruce M. Metzger, The Text of the New Testament (2005), p. 106.

- ^ H. J. White, The Codex Amiatinus and its Birthplace, in: Studia Biblica et Ecclesiasctica (Oxford 1890), Vol. II, p. 273.

- ^ Richard Marsden, Amiatinus, Codex, in: Blackwell encyclopaedia of Anglo-Saxon England, ed. Michael Lapidge,John Blair,Simon Keynes, Wiley-Blackwell, 2001, s. 31.

- ^ Dom John Chapman, The Codex Amiatinus and the Codex grandior in: Notes on the early history of the Vulgate Gospels, Clarendon Press, Oxford 1908, pp. 2-8.

Further reading

- Text

- Ferdinand Florens Fleck, Novum Testamentum Vulgatae editionis juxta textum Clementis VIII. Romanum ex Typogr. Apost. Vatic. A 1592 accurate expressum (Lipsiae 1840).

- Constantinus Tischendorf, Codex Amiatinus. Novum Testamentum Latine interpreter Hieronymo, (Lipsiae 1854).

- The City and the Book: International Conference Proceedings, Florence, 2001 http://www.florin.ms/aleph.html

- Alphabet and Bible: From the Margins to the Centre. Paper at Monte Amiata, 2009. http://www.florin.ms/AlphabetBible.html

- Makepeace, Maria. "The 1,300 year pilgrimage of the Codex Amiatinus". Umilta Website. http://www.umilta.net/pandect.html. Retrieved 2006-06-07. Contains link to facsimile project, as well.

- H. J. White, The Codex Amiatinus and its Birthplace, in: Studia Biblica et Ecclesiasctica (Oxford 1890), Vol. II, pp. 273-308. reprint from 2007

External links

- The Codex Amiatinus and the Codex grandior

- Image of the codex, folio 950

- "Age of Conquest". David Dimbleby. Seven Ages of Britain. BBC 1. 33:38 minutes in. Retrieved on 21 Nov 2010.

- The Cambridge History of the Bible, Cambridge University Press 2008, pp. 117-119, 130.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed (1913). Catholic Encyclopedia. Robert Appleton Company.Categories:

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed (1913). Catholic Encyclopedia. Robert Appleton Company.Categories:- Hiberno-Saxon manuscripts

- Illuminated biblical manuscripts

- Vulgate manuscripts

- 8th-century biblical manuscripts

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.