- Longsword

-

For other uses, see Longsword (disambiguation).

Longsword

Swiss longsword, ca. 1500

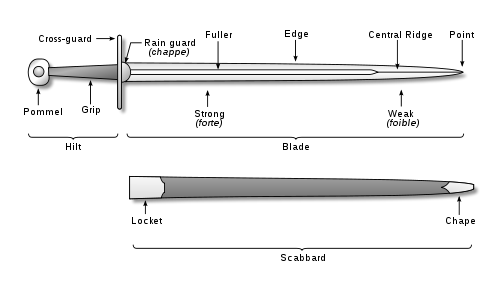

(Morges museum)Type Sword Service history In service ca. 1350 - 1550 Specifications Weight avg. 1.5 kg (3.3 lb) Length avg. 105–120 cm (41–47 in) Blade length avg. 90–92 cm (35–36 in) Width 4.14cm-3.1cm then sharp point Blade type Double-edged, straight bladed Hilt type Two-handed cruciform, with pommel The longsword (of which stems the variation called the bastard sword) is a type of European sword designed for two-handed use, current during the late medieval and Renaissance periods, approximately 1350 to 1550 (with early and late use reaching into the 13th and 17th centuries).

Longswords have long cruciform hilts with grips over 10 to 15 cm length (providing room for two hands). Straight double-edged blades are often over 1 m to 1.2 m (40" to 48") length, and weigh typically between 1.2 and 1.8 kg (2½ to 4 lb), with light specimens just below 1 kg (2.2 lb), and heavy specimens just above 2 kg (4½ lb).[1]

Contents

Terminology

Further information: Oakeshott typology#Type XIIIThe term "longsword" is ambiguous, and refers to the "bastard sword" only where the late medieval to Renaissance context is implied. "Longsword" in other contexts has been used to refer to Bronze Age swords, Migration period and Viking swords, rapiers, as well as the early modern dueling sword.

Historical (15th to 16th century) terms for this type of sword included German langes schwert, Spanish espadón, montante or mandoble, Italian spadone or spada longa (lunga), Portuguese montante and French passot. The Gaelic claidheamh mòr means "great sword"; anglicized as claymore it came to refer to the Scottish type of longsword with V-shaped crossguard. Historical terminology overlaps with that applied to the Zweihänder sword in the 16th century: French espadon, Spanish espadón or Portuguese montante may also be used more narrowly to refer to these large swords. The French épée de passot may also refer to a medieval single-handed sword optimized for thrusting.

The French épée bâtarde as well as the English bastard sword originates in the 15th or 16th century, originally in the general sense of "irregular sword, sword of uncertain origin", but by the mid-16th century could refer to exceptionally large swords.[2] The Masters of Defence competition organised by Henry VIII in July 1540 listed two hande sworde and bastard sworde as two separate items.[3] It is uncertain whether the same term could still be used to other types of smaller swords, but antiquarian usage in the 19th century established the use of "bastard sword" as referring unambiguously to these large swords.[4]

The term "hand-and-a-half sword" is modern (late 19th century).[5] During the first half of the 20th century, the term "bastard sword" was used regularly to refer to this type of sword, while "long sword" or "long-sword", if used at all, referred to the rapier (in the context of Renaissance or Early Modern fencing).[6] Even though "long sword" is the historical term for the weapon, contemporary use of "long-sword" or "longsword" only resurfaces in the 2000s in the context of reconstruction of the German school of fencing, translating the German langes schwert.[7]

Morphology

Further information: EstocLate Middle Ages

The Oakeshott typology mentions the sword subtypes XIIa and XIIIa from the latter part of the High Middle Ages, c. 1250-1350, as the forerunners of the later longswords. Calling these two subtypes 'great swords', Oakeshott lists their hand-and-half grip (with enough room for the off-hand to hold the pommel securely) and relatively large blade (roughly 36 inches or 910 mm), for the most part longer and broader than contemporary arming swords. In the Late Middle Ages, c. 1350-1500, various longsword subtypes emerge with their hand-and-half grip:

- average blade length about 32 inches (810 mm): subtype XVIa (early 14c)

- average blade length about 34 inches (860 mm): subtype XVIIIc (mid 15c to early 16c)

- average blade length roughly 34 inches (860 mm) with approximate range from 30 to 38 inches (800 to 900 mm): type XX (14c and 15c), subtypes XXa (14c and 15c),

- average blade length about 35 inches (890 mm): subtype XVa (end of 13c to early 16c), XVIIa (mid 14c to early 15c)

- average blade length roughly 39 inches (990 mm) with averages about 36 to 42 inches (around 1 m): subtypes XVIIIa (mid 14c to early 15c), XVIIIb (early 15c to mid 16c), XVIIId (mid 15c to early 16c), XVIIIe (mid 15c to early 16c).

Notably, this last subtype XVIIIe sometimes exhibits a proper two-handed grip. While all of the above subtypes of the Late Middle Age can count as 'longswords', the Oakeshott typology does not go on to list the properly two-handed longswords of the Renaissance Age, whose blades are truly huge, such as the Scottish claymore (blade length roughly 42 inches or 1.07 m) and the German zweihänder (blade length roughly 53 inches or 1.35 m).

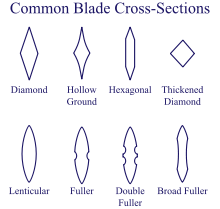

The blade of the medieval longsword is straight and predominantly double edged. The construction of the blade is relatively thin, with strength provided by careful blade geometry. Over time, as is evidenced in the Oakeshott typology and other similar systems, the blades of longswords become slightly longer, thicker in cross-section, less wide, and considerably more pointed. This design change is largely attributed to the use of plate armour as an effective defense, more or less nullifying the ability of a sword cut to break through the armour system. Instead of cutting, long swords were then used more to thrust against opponents in plate armour, requiring a more acute point and a more rigid blade. However, the cutting capability of the longsword was never entirely removed, as in some later rapiers, but was supplanted in importance by thrusting capability.

Blades differ considerably in cross-section, as well as in length and width. The two most basic forms of blade cross-section are the lenticular and diamond. Lenticular blades are shaped like thin doubly convex lenses, providing adequate thickness for strength in the center of the weapon while maintaining a thin enough edge geometry to allow a proper cutting edge to be ground. The diamond shaped blade slopes directly up from the edges, without the curved elements of the lenticular blade. The central ridge produced by this angular geometry is known as a riser, the thickest portion of the blade that provides ample rigidity. These basic designs are supplemented by additional forging techniques that incorporated slightly different variations of these cross-sections.

The most common among these variations is the use of fullers and hollow-ground blades. While both of these elements concern themselves with the removal of material from the blade, they differ primarily in location and final result. Fullers are grooves or channels that are removed from the blade, in longswords, usually running along the center of the blade and originating at or slightly before the hilt. The removal of this material allows the smith to significantly lighten the weapon without compromising the strength to the same extent, much as in the engineering of steel I-beams. On some cutting blades the fuller may run nearly the entire length of the weapon, while the fuller stops one-third or half-way down other blades. Hollow-ground blades have concave portions of steel removed from each side of the riser, thinning the edge geometry while keeping a thickened area at the center to provide strength for the blade.

A variety of hilt styles exist for longswords, with the style of pommel and quillion (crossguard) changing over time to accommodate different blade properties and to fit emerging stylistic trends.

The evolution of the sword before and after the development of the longsword was not entirely linear. Swords of an older type may have coexisted with newer variants for quite some time, making it difficult to trace a single path of sword evolution. Instead, the course of sword development is layered with some swords evolving from a previous type of sword, acting as its able contemporary, and eventually being abandoned while the original design continued in use for some time afterward. Similarly, variants of a particular type of sword may have come about not to replace it, but to simply coexist with it until a new evolution brought a close to both older types of weapons. Such situations present both the path of sword development as a whole and the encompassed rise and fall of the longsword as chronologically nebulous and confused by broad definitions, both modern and contemporary.

The relatively comprehensive Oakeshott typology was created by historian and illustrator Ewart Oakeshott as a way to define and catalogue swords based on physical form, though a rough sense of chronology is apparent. This typology does not set forth a prototypical definition for the longsword, however. Instead, it separates the broad field of weaponry into many exclusive types based on their predominant physical characteristics including blade shape and hilt configuration. The typology also focuses on the smaller, and in some cases contemporary,[8] single-handed swords like the arming sword.

The longsword, with its longer grip and blade, appears to have become popular during the 14th century and remained in common use, as shown through period art and tale, from 1250 to 1550.[9] The longsword was a powerful and versatile weapon, but was not considered the only weapon needed for learning the arts of war. Johannes Lichtenauer, an influential Fechtbuch (combat manual) author, writes that young knights should learn to "wrestle well, (and) skilfully wield spear, sword, and dagger in a manly way."[10]

It is in the Types XIIa and XIIIa that the first early variants of the longsword arise as simply longer versions of the single-handed sword. There are rare archeological findings of swords of this type from as early as the late 12th century.[11] Boasting both increased grip length and increased blade lengths, these weapons would have been powerful hewing swords, perhaps developed to further combat the prevalence of mail[12] and plate armour. These weapons also firmly fit the modern colloquial term "hand-and-a-half sword", as Oakeshott notes, because they do not provide a full two-hand grip as do some early extant specimens and the 16th century Bidenhänder. Hand and a half swords were so called because they could be either a one or two handed weapon.

Renaissance

Distinct "bastard sword" hilt types develop during the first half of the 16th century. Oakeshott (1980:130) distinguishes twelve different types. These all seem to have originated in Bavaria and in Switzerland. By the late 16th century, early forms of the basket-hilt emerge on this type of sword. Beginning about 1520, the Swiss sabre (schnepf) in Switzerland began to replace the straight longsword, inheriting its hilt types, and the longsword had fallen out of use in Switzerland by 1550. In southern Germany, it persisted into the 1560s, but its use also declined during the second half of the 16th century. There are two late examples of longswords kept in the Swiss National Museum, both with vertically grooved pommels and elaborately decorated with silver inlay, and both belonging to Swiss noblemen in French service during the late 16th and early 17th century, Gugelberg von Moos and Rudolf von Schauenstein.[13] The longsword or bastard-sword was also made in Spain, appearing relatively late, known as the espadon or the montante.

Fighting with the longsword

For more details on this topic, see Historical fencing.History

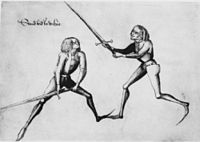

Codified systems of fighting with the longsword existed from the later 14th century, with a variety of styles and teachers each providing a slightly different take on the art. The longsword was a quick, effective, and versatile weapon capable of deadly thrusts, slices, and cuts.[14] The blade was generally used with both hands on the hilt, one resting close to or on the pommel. The weapon may be held with one hand during disarmament or grappling techniques. In a depiction of a duel, individuals may be seen wielding sharply pointed longswords in one hand, leaving the other hand open to manipulate the large dueling shield.[15] Another variation of use comes from the use of armour. Half-swording was a manner of using both hands, one on the hilt and one on the blade, to better control the weapon in thrusts and jabs. This versatility was unique, as multiple works hold that the longsword provided the foundations for learning a variety of other weapons including spears, staves, and polearms.[14][16] Use of the longsword in attack was not limited only to use of the blade, however, as several Fechtbücher explain and depict use of the pommel and cross as offensive weapons.[17] The cross has been shown to be used as a hook for tripping or knocking an opponent off balance.[14] Some manuals even depict the cross as a hammer. [18]

What is known of combat with the longsword comes from artistic depictions of battle from manuscripts and the Fechtbuch of Medieval and Renaissance Masters. Therein the basics of combat were described and, in some cases, depicted. The German school of swordsmanship includes the earliest known longsword Fechtbuch, a manual from approximately 1389 mistakenly accredited to Hanko Döbringer.[19] This manual, unfortunately for modern scholars, was written in obscure verse. It was through students of Liechtenauer, like Sigmund Ringeck, who transcribed the work into more understandable prose[20] that the system became notably more codified and understandable.[21] Others provided similar work, some with a wide array of images to accompany the text.[22]

The Italian school of swordsmanship was the other primary school of longsword use. The 1410 manuscript by Fiore dei Liberi presents a variety of uses for the longsword. Like the German manuals, the weapon is most commonly depicted and taught with both hands on the hilt. However, a section on one-handed use is among the volume and demonstrates the techniques and advantages, such as sudden additional reach, of single-handed longsword play.[23] The manual also presents half-sword techniques as an integral part of armoured combat.

Both schools declined in the late 16th century, with the later Italian masters forgoing the longsword and focusing primarily on rapier fencing. The last known German manual to include longsword teaching was that of Jakob Sutor, published in 1612. In Italy, spadone, or longsword, instruction lingered on in spite of the popularity of the rapier, at least into the mid-17th century (Alfieri's Lo Spadone of 1653), with a late treatise of the "two handed sword" by one Giuseppe Colombani, a dentist in Venice dating to 1711. A tradition of teaching based on this has survived in contemporary French and Italian stick fighting. (See, for instance, Giuseppe Cerri's Trattato teorico e pratico della scherma di bastone of 1854.) However, there can be no doubt that the heyday of the longsword on the battlefield was over by 1500.

German school of fencing

Main article: German school of fencingBloßfechten

Unarmoured longsword fencers (plate 25 of the 1467 manual of Hans Talhoffer)

Unarmoured longsword fencers (plate 25 of the 1467 manual of Hans Talhoffer)

Bloßfechten (blosz fechten) or "bare fighting" is the technique of fighting without significant protective armour such as plate, mail

The lack of significant torso and limb protection leads to the use of a large amount of cutting and slicing techniques in addition to thrusts. These techniques could be nearly instantly fatal or incapacitating, as a thrust to the skull, heart, or major blood vessel would cause massive trauma. Similarly, strong strikes could cut through skin and bone, effectively amputating limbs. The hands and forearms are a frequent target of some cuts and slices in a defensive or offensive maneuver, serving both to disable an opponent and align the swordsman and his weapon for the next attack.

Harnischfechten

Harnischfechten, or "armoured fighting" (German kampffechten, or vechten in harnasch zu fuess lit. "fighting in armour on foot"), depicts fighting in full plate armour.[24]

The increased defensive capability of a man clad in full plate armour caused the use of the sword to be drastically changed. While slashing attacks were still moderately effective against infantry wearing half-plate armor, cutting and slicing attacks against an opponent wearing plate armour were almost entirely ineffective in providing any sort of slashing wound as the sword simply could not cut through the steel.[25] Instead, the energy of the cut becomes essentially pure concussive energy. The later hardened plate armours, complete with ridges and roping, actually posed quite a threat against the careless attacker. It is considered possible for strong blows of the sword against plate armour to actually damage the blade of the sword, potentially rendering it much less effective at cutting and producing only a concussive effect against the armoured opponent.

To overcome this problem, swords began to be used primarily for thrusting. The weapon was used in the half-sword, with one or both hands on the blade. This increased the accuracy and strength of thrusts and provided more leverage for Ringen am Schwert or "Wrestling at/with the sword". This technique combines the use of the sword with wrestling, providing opportunities to trip, disarm, break, or throw an opponent and place them in a less offensively and defensively capable position. During half-swording, the entirety of the sword works as a weapon, including the pommel and crossguard which function as a mace as shown in the Mordstreich.[25]

See also

- Historical European Martial Arts

- Oakeshott typology

- Ricasso

- Side-sword

- Claymore

- Waster

- Jian

- Katana

- Tachi

- Training

References

- ^ Clements, John. What did historical swords weigh?

- ^ Qui n'étoit ni Françoise , ni Espagnole, ni proprement Lansquenette, mais plus grande que pas une de ces fortes épées ("[a sword] which was neither French, nor Spanish, nor properly Landsknecht [German], but larger than any of these great swords." Jacob Le Duchat (ed.), Oeuvres de Maitre François Rabelais, Jean-Frédéric Bernard, 1741, p. 129 (footnote 5).)

- ^ Joseph Strutt The sports and pastimes of the people of England from the earliest period: including the rural and domestic recreations, May games, mummeries, pageants, processions and pompous spectacles, 1801, p. 211.

- ^ Oakeshott (1980).

- ^ attested in a New Gallery exhibition catalogue, London 1890.

- ^ see e.g. A general guide to the Wallace Collection, 1933, p. 149.

- ^ A nonce attestation of "long-sword" in the sense of "heavy two-handed sword" is found in Principles of stage combat (1983). Carl A. Thimm, A Complete Bibliography of Fencing & Duelling (1896) uses "long sword (Schwerdt) on p. 220 as direct translation from a German text of 1516, and "long sword or long rapier" in reference to George Silver (1599)on p. 269. Systematic use of the term only from 2001 beginning with C. H. Tobler, Secrets of German medieval swordsmanship (2001), ISBN 9781891448072.

- ^ Oakeshott, Ewart. The Sword in the Age of Chivalry. Boydell Press 1994. Page 18-19.

- ^ Oakeshott, Ewart. The Sword in the Age of Chivalry. Boydell Press 1994. Page 56.

- ^ Lindholm, D. & Svard, P. Sigmund Ringneck's Knightly Art of the Longsword Paladin Press, 2003. Page 17.

- ^ Sotheby's: Antique Arms, Armour, and Militaria 26 June 2003. Item 31. "A fine Medieval 'Great' sword second half of the 12th/first half of the 13th century."

- ^ Oakeshott, Ewart. The Sword in the Age of Chivalry. Boydell Press 1994. Page 40.

- ^ Oakeshott (1980), p. 133. See also Peter Finer, "Two further silver-encrusted swords possessing pommels of this type can be seen in the Schweizerisches Landesmuseum, Zurich (inv. nos LM 16736 and 16988). The first belonged to Hans Gugelberg von Moos (recorded 1562–1618), and the second to Rudolf von Schauenstein (recorded 1587–1626), whose name appears on its blade along with the date 1614."

- ^ a b c Rector, Mark. Medieval Combat: A Fifteenth-Century Illustrated Manual of Swordfighting and Close-Quarter Combat. Green Hill Books, 2000. Page 15-16.

- ^ Rector, Mark. Medieval Combat: A Fifteenth-Century Illustrated Manual of Swordfighting and Close-Quarter Combat. Green Hill Books, 2000. Plate 128-150.

- ^ Lindholm, David. Fighting with the Quarterstaff: A Modern Study of Renaissance Technique. The Chivalry Bookshelf, 2006. Page 32.

- ^ Rector, Mark. Medieval Combat: A Fifteenth-Century Illustrated Manual of Swordfighting and Close-Quarter Combat. Green Hill Books, 2000. Plate 67, 73 - 74.

- ^ Hans Tallhoffer "Fechtbuch"

- ^ Liechtenauer, Johannes. MS 3227a

- ^ Ringeck, Sigmund. MS Dresd. C 487

- ^ Lindholm, D. & Svard, P. Sigmund Ringneck's Knightly Art of the Longsword Paladin Press, 2003. Page 11.

- ^ Talhoffer, Hans. Thott 290 2

- ^ dei Liberi, Fiore. Flos Duellatorum.

- ^ Clements, John. Medieval and Renaissance Fencing Terminology

- ^ a b Lindholm, David & Svärd, Peter. Signmund Ringeck's Knightly Arts of Combat. Paladin Press, 2006. Page 219.

- Cvet, David M.. Study of the Destructive Capabilities of the European Longsword. Journal of Western Martial Art. February 2002.

- Dawson, Timothy. A club with an edge. Journal of Western Martial Art. February 2005.

- Hellqvist, Björn. Oakeshott's Typology - An Introduction. Journal of Western Martial Art. November 2000.

- Melville, Neil H. T.. The Origins of the Two-Handed Sword. Journal of Western Martial Art. January 2000.

- Shore, Anthony. The Two-Handed Great Sword - Making lite of the issue of weight. Journal of Western Martial Art. October 2004.

External links

- "Oakeshott's Typology of the Medieval Sword: A Summary", Albion Armorers, inc. 2005, retrieved May 22, 2010.[1] This quick survey lists the types and sample illustrations of the Oakeshott Typology. Extremely useful, but note, the webpage updates the statistics of the original Oakeshott Typology, with the findings from later research.

Further reading

- Clements, John. Medieval Swordsmanship: Illustrated Methods and Techniques. Paladin Press, 1998. ISBN 1-58160-004-6

- Clements, John et al. Masters of Medieval and Renaissance Martial Arts: Rediscovering The Western Combat Heritage. Paladin Press, 2008. ISBN 978-1-58160-668-3

- Lindholm, David & Peter Svärd, Sigmund Ringeck's Knightly Art of the Longsword, Paladin Press (2003), ISBN 1-58160-410-6

- Lindholm, David, & Peter Svärd. Knightly Arts of Combat - Sigmund Ringeck's Sword and Buckler Fighting, Wrestling, and Fighting in Armor. Paladin Press, 2006. ISBN 1-58160-499-8

- Oakeshott, R. E., European weapons and armour: From the Renaissance to the industrial revolution (1980), 129-135.

- Thomas, Michael G. The Fighting Man's Guide to German Longsword Combat, SwordWorks (2007), ISBN 1-90651-200-0

- Tobler, Christian H. Secrets of German Medieval Swordsmanship (2001), ISBN 1-891448-07-2

- Tobler, Christian H. Fighting with the German Longsword (2004), ISBN 1-891448-24-2

- Windsor, Guy. The Swordsman's Companion: A Modern Training Manual for Medieval Longsword (2004), ISBN 1-891448-41-2

- Zabinski, Grzegorz & Bartlomiej Walczak. The Codex Wallerstein: A Medieval Fighting Book from the Fifteenth Century on the Longsword, Falchion, Dagger, and Wrestling. Paladin Press, 2002. ISBN 1-58160-339-8

Categories:- Medieval European swords

- Renaissance-era swords

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.