- Medicine in ancient Rome

-

Medicine in ancient Rome combined various techniques using different tools and rituals. Ancient Roman medicine included a number of specializations such as internal medicine,[clarification needed] ophthalmology and urology. The Romans favoured the prevention of diseases over the cures of them; unlike in Greek society where health was a personal matter, public health was encouraged by the government at the time; they built bath houses and aqueducts to pipe water to the cities. Many of the larger cities, such as Rome, boasted an advanced sewage system, the likes of which would not be seen in the Western world again until the late 17th century onward. However, the Romans did not fully understand the involvement of germs in disease.

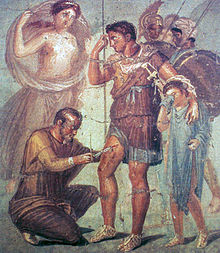

Roman surgeons carried a tool kit which contained forceps, scalpels, catheters and arrow extractors. The tools had various uses and were boiled in hot water before each use. In surgery, surgeons used painkillers such as opium and scopolamine for treatments, and acetum (the acid in vinegar) was used to wash wounds. The Greeks used temples and religious belief to try to cure people, yet the Romans developed specific hospitals which enabled the patients to be fully rested and relaxed so they could completely recover. By staying in the hospitals, the doctors (which now had different levels of qualification) were able to observe the illness rather than rely on the supernatural to cure them.[clarification needed][citation needed]

Contents

Greek influences on Roman Medicine

Many Greek medical ideas were adopted by the Romans and Greek medicine had a huge influence on Roman medicine. The first doctors to appear in Rome were Greek, captured as prisoners of war. Greek doctors would later move to Rome because they could make a good living there, or a better one than in the Greek cities.

The Romans also conquered the city of Alexandria, with its libraries and its universities. In Ancient times, Alexandria was an important centre for learning and its Great Library held countless volumes of information, many of which would have been on medicine. Here, doctors were allowed to carry out dissections which led to the discovery of many important medical advances, such as the discovery that the brain sends messages to the body.

Greek Medicine revolved heavily around the theory of the Four Humours and texts by Hippocrates and his followers (Hippocratic Writings), who were all Greek. These ideas and writings were also used in Roman medicine.

Roman Medicine also encompassed the spiritual beliefs of the Greeks (see below).

Dioscorides

Pedanius Dioscorides (ca. 40-ca. 90) was an ancient Greek physician, pharmacologist and botanist from Anazarbus, Cilicia, Asia Minor, who practised in ancient Rome during the time of Nero. Dioscorides is famous for writing a five volume book De Materia Medica that is a precursor to all modern pharmacopeias, and is one of the most influential herbal books in history.

Soranus

Main article: Soranus of EphesusSoranus was a Greek physician, born at Ephesus, who lived during the reigns of Trajan and Hadrian (AD 98-138). According to the Suda, he practised in Alexandria and subsequently in Rome. He was the chief representative of the school of physicians known as "Methodists." His treatise Gynaecology is extant (first published in 1838, later by V. Rose, in 1882, with a 6th-century Latin translation by Muscio, a physician of the same school).

Galen

Galen (AD 129[1] –ca. 200 or 216) of Pergamon was a prominent ancient Greek[2] physician, whose theories dominated Western medical science for well over a millennium. By the age of 20, he had served for four years in the local temple as a therapeutes ("attendant" or "associate") of the god Asclepius. Although Galen studied the human body, dissection of human corpses was against Roman law, so instead he used pigs, apes, and other animals. Galen moved to Rome in 162. There he lectured, wrote extensively, and performed public demonstrations of his anatomical knowledge. He soon gained a reputation as an experienced physician, attracting to his practice a large number of clients. Among them was the consul Flavius Boethius, who introduced him to the imperial court, where he became a physician to Emperor Marcus Aurelius. Despite being a member of the court, Galen reputedly shunned Latin, preferring to speak and write in his native Greek, a tongue that was actually quite popular in Rome. He would go on to treat Roman luminaries such as Lucius Verus, Commodus, and Septimius Severus. However, in 166 Galen returned to Pergamon again, where he lived until he went back to Rome for good in 169.

Ancient Roman Medicine

The Ancient Romans, like the Greeks and Egyptians, had a huge impact on health and medicine.[3] Even then, the Romans knew poor hygiene was a constant source of disease, so public bath houses and other public hygienic facilities were built. The Romans learned a great deal from the ancient Greeks, whom they first came into contact with around 500 BC. By the year 27 BC, Greece and many of its surrounding islands had become Roman territory, therefore many of the Greek medicinal methods and ways of treatment became a part of everyday Roman life. As the Romans expanded into Greece, Greek doctors came to Rome and other parts of Italy. Many of these doctors were prisoners of war and could be purchased by wealthy Romans who wanted a doctor in their household. Many of these prisoners, however, bought their freedom from their owners and started their own practices in Rome. The Greek physicians often had the support of the emperors and they were very popular amongst the Roman public. Prior to this influx of medical knowledge, there was no separate medical profession in the Roman Empire. It was believed that the head of every household knew enough about herbs and medicine to treat illnesses within his family. The Romans also believed that a healthy mind meant a healthy body; If you kept fit, you would keep healthy.

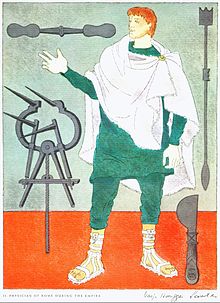

Surgical Tools used in ancient Rome[4]

Scalpels: Could be made of either steel or bronze. Ancient scalpels had almost the same form and function as those of today. The most ordinary type of scalpels in antiquity were the longer, steel scalpels. These long scalpels could be used to make a variety of incisions, but they seem to be particularly suited for deep or long cuts. Smaller, bronze scalpels, referred to as bellied scalpels, were also used frequently by surgeons in antiquity since the shape allowed for delicate and precise cuts to be made.

Hooks: A common instrument used regularly by Roman and Greek doctors. The ancient doctors used two basic types of hooks: sharp hooks and blunt hooks. Blunt hooks were used primarily as probes for dissection and for raising blood vessels. Sharp hooks, on the other hand, were used to hold and lift small pieces of tissue so that they could be extracted, and to retract the edges of wounds.

Bone Drills: Driven in their rotary motion by means of a thong in various configurations. Roman and Greek physicians used bone drills in order to remove diseased bone tissue from the skull and to remove foreign objects (such as a weapon) from a bone.

Forceps: Forceps were often used in conjunction with bone drills. They were used by ancient doctors to extract small fragments of bone which could not be grasped by the fingers.

Catheters: Used in order to open up a blocked urinary tract which allowed urine to pass freely from the body. Early catheters were hollow tubes made of steel or bronze, and had two basic designs. There were catheters with a slight S curve for male patients and a straighter one for females. There were similar shaped devices called bladder sounds that were used to probe the bladder in search of calcifications.

Uvula Crushing Forceps: These finely toothed jawed forceps were designed to facilitate the amputation of the uvula. The procedure called for the physician to crush the uvula with forceps before cutting it off in order to prevent hemorrhaging.

Vaginal Specula: Among the most complex instruments used by Roman and Greek physicians. Most of the vaginal specula that have survived and been discovered consist of a screw device which, when turned, forces a cross-bar to push the blades outwards.

Spatula: This instrument was used to mix and apply various ointments to patients.

Surgical saw: This instrument was used to cut through bones in amputations and surgeries.

Medicines

Medicinal herbs

Some Ancient Roman herbs used in medicine were:

Fennel: It was thought to have calming properties.

Elecampane: Used to help with digestion.

Sage: Although it had little medicinal value, it had great religious value.

Garlic: Beneficial for health, particularly of the heart.

Fenugreek: Used in the treatment of pneumonia.

Silphium: Used for a wide variety of ailments and conditions—especially for birth control.

Willow: Is used as an antiseptic

Asclepieions in Roman Medicine

When the Roman Army conquered Greece they adopted many of their medicinal beliefs and ideas. The cult of Asclepios had spread across much of Greece and numerous temples (asclepieions) had been built in his name. These Asclepieions (or Asklepieions) were places of healing. They contained baths, gardens and other facilities designed to improve people's health. People who were being treated in the Asclepieions would sleep in front of a statue of the Greek God in the hope that he would heal them in their sleep. Though several accounts have been recovered, detailing the progress in health made by people admitted to the Asclepieions, it is unlikely that they were based on fact; they may simply have been used as propaganda.

Evidence of Traveling Surgeon

At the site of the Roman Plemmirio shipwreck (c. AD 200) near Siracusa, Italy, a comprehensive instrumentarium[5] was found. Numerous other items, which could range from bone mallets to urinary catheters, remain at the site. Although it is not certain, it is highly likely that these were the tools of an oculist- an eye surgeon- and not equipment from the ship’s first aid box. In support of this theory, over 1500 ships have been discovered in the Mediterranean, and there is a consequent lack of evidence for surgeons in ship crews. The ship was destined for Rome, after sailing down to North Africa, where it transported amphorae, so it is a safe assumption that this surgeon was also destined for Rome. Although surgeon’s kits have been found in graves, this is the first finding of a kit that was in-use, before the ship was destroyed when it smashed into a cliff on its return to Rome.

Tiber Island

Tiber Island in Rome was once the location of an ancient temple to Aesculapius, the Greek god of medicine and healing.

Accounts say that in 293 BC, there was a great plague in Rome. Upon consulting the Sibyl, the Roman Senate decided to build a temple to Aesculapius, the Greek god of healing, and sent a delegation to Epidauros to obtain a statue of the deity. They obtained a snake from a temple and put in on board their ship. It immediately curled itself around the ship's mast and this was deemed as a good sign by them. Upon their return up the Tiber river, the snake slithered off the ship and swam onto the island. They believed that this was a sign from Aesculapius, a sign which meant that he wanted his temple to be built on that island.

References

- ^ "Galen". Encyclopædia Britannica. IV. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.. 1984. pp. 385.

- ^ Galen of Pergamum

- ^ Medicine in Ancient Rome

- ^ Surgical tools used in ancient Rome

- ^ Medicine at Sea: Underwater Discovery of Roman Surgical Equipment

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

External links

- (French)(English)Antique medicine website

Categories:- Ancient Roman medicine

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.