- Materia medica

-

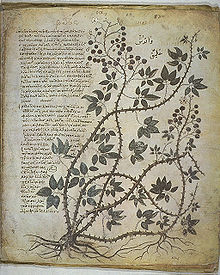

Page from the 6th century Vienna Dioscurides, an illuminated version of the 1st century De Materia Medica

Page from the 6th century Vienna Dioscurides, an illuminated version of the 1st century De Materia Medica

Materia medica is a Latin medical term for the body of collected knowledge about the therapeutic properties of any substance used for healing (i.e., medicines). The term 'materia medica' derived from the title of a work by the Ancient Greek physician Pedanius Dioscorides in the 1st century AD, De materia medica libre. In Latin, the materia medica literally means "medical material/substance" and was used from the period of the Roman Empire until the twentieth century, but has now been generally replaced in medical education contexts by the term pharmacology.

Contents

History

Ancient

The earliest known writing about medicine was a hundred and ten page Egyptian papyrus. It was supposedly written by the god, Thoth, about sixteen centuries before the common era. The Ebers papyrus is an ancient recipe book dated to approximately 1552 B.C.E. It contains a mixture of magic and medicine with invocations to banish disease and a catalogue of useful plants, minerals, magic amulets and spells. [1] The most famous Egyptian physician was Imhotep, in Memphis about 3500 B.C.E. Imhotep’s materia medica consisted of procedures for treating head and torso injuries, tending of wounds, and prevention and curing infections and advanced principles of hygiene.

In India, the Ayurveda is traditional medicine that emphasizes plant-based treatments, hygiene, and balance in the body’s state of being. Indian materia medica included knowledge of plants, where they grow in all season, methods for storage and shelf life of harvested materials. It also included directions for making juice from vegetables, dried powders from herb, cold infusions and extracts. [2]

The earliest Chinese manual of materia medica, the Shennong Bencao Jing (Shennong Emperor's Classic of Materia Medica), was compiled in the first century AD during the Han dynasty, but it was attributed to the mythical Shennong. It lists some 365 medicines of which 252 of them are herbs. Earlier literature included lists of prescriptions for specific ailments, exemplified by a manuscript Recipes for Fifty-Two Ailments, found in the Mawangdui tomb, which was sealed in 168 BC. Succeeding generations augmented the Shennong Bencao Jing, as in the Yaoxing Lun (Treatise on the Nature of Medicinal Herbs), a 7th century Tang Dynasty treatise on herbal medicine.

In Greece, Hippocrates, (born 460 B.C.E.), was a philosopher and known as the Father of Medicine. He founded a school of medicine that focused on treating the causes of disease rather than its symptoms. Disease was dictated by natural laws and therefore could be treated through close observation of symptoms. Hippocrates stressed discovering and eliminating the causes of diseases. His treatises, Aphorisms and Prognostics discusses 265 drugs, the importance of diet and external treatments for diseases. [2] Theophrastus, (390-280 B.C.E.), was a disciple of Aristotle and a philosopher of natural history, considered by historians as the “Father of Botany.” He wrote a treatise entitled, Historia Plantarium, about 300 B.C.E. It was the first attempt to organize and classify plants, plant lore, and botanical morphology in Greece. It provided physicians with a rough taxonomy of plants and details of medicinal herbs and herbal concoctions. [3]

Galen, was a philosopher, physician, pharmacist and a prolific medical writer. He collected and compiled an extensive record of the medical knowledge of his day and added the results of his own observations. He wrote on the structure of organs, but not their uses; the pulse and its association with respiration; the arteries and the movement of blood; and the uses of theriacs. “In treatises such as On Theriac to Piso, On Theriac to Pamphilius, and On Antidotes, Galen identified theriac as a sixty-four-ingredient compound, able to cure any ill known.” [4] His work was rediscovered in the fifteenth century and became the authority on medicine and healing for the next two centuries. His medicine was based on the regulation of the four humors (blood, phlegm, black bile, and yellow bile) and their properties (wet, dry, hot, and cold). [5]

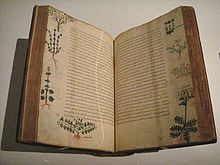

Dioscorides, De Materia Medica, Byzantium, 15th century.

Dioscorides, De Materia Medica, Byzantium, 15th century.

Dioscorides De Materia Medica in Arabic, Spain, 12th-13th century.

Dioscorides De Materia Medica in Arabic, Spain, 12th-13th century.

The Greek physician Pedanius Dioscorides, of Anazarbus in Asia Minor, wrote a five volume treatises concerning medical matters , entitled Περί ύλης ιατρικής in Greek or De materia medica in Latin. This famous commentary covered about 500 plants along with a number of therapeutically useful animal and mineral products. It documented the description and direct observations of plants, fruits, seeds, the effects that various drugs had on patients. De materia medica was the first extensive drug affinity system that included about a thousand natural product drugs (mostly plant-bases), 4,740 medicinal usages for drugs, and 360 medical properties (antiseptic, anti-inflammatory, stimulants, etc.) Dioscorides' plant descriptions use an elementary classification, though he cannot be said to have used botanical taxonomy. Book one describes the uses for aromatic oils, salves and ointments, trees and shrubs,and fleshy fruits, even if not aromatic. Book two included uses for animals, parts of animals, animal products, cereals, leguminous, malvaceous, cruciferous, and other garden herbs. Book three detailed the properties of roots, juices, herbs and seeds,used for food or medicine. Book four continued to describe the uses for roots and herbs, specifically narcotic and poisonous medicinal plants. Book five dealt with the medicinal uses for wine and metallic ores.[6] [7] It is a precursor to all modern pharmacopeias, and is considered one of the most influential herbal books in history. It remained in use until about 1600 B.C.E. [8]

Medieval

Later in the medieval Islamic world, Muslim botanists and Muslim physicians significantly expanded on the earlier knowledge of materia medica. For example, al-Dinawari described more than 637 plant drugs in the 9th century,[9] and Ibn al-Baitar described more than 1,400 different plants, foods and drugs, over 300 of which were his own original discoveries, in the 13th century.[10] The experimental scientific method was introduced into the field of materia medica in the 13th century by the Andalusian-Arab botanist Abu al-Abbas al-Nabati, the teacher of Ibn al-Baitar. Al-Nabati introduced empirical techniques in the testing, description and identification of numerous materia medica, and he separated unverified reports from those supported by actual tests and observations. This allowed the study of materia medica to evolve into the science of pharmacology.[11] Avicenna, 980-1037 C.E., was a Persian philosopher, physician, and Islamic scholar. He wrote about 40 books on medicine. His two most famous books are the Canon of Medicine and The Book of Healing and were used in medieval universities as medical textbooks. He did much to popularize the connection between Greek and Arabic medicine translating works by Hippocrates, Aristotle and Galen into Arabic. Avicenna stressed the importance of diet, exercise, and hygiene. He also was the first to describe parasitic infection, to use urine for diagnostic purposes and discouraged physicians from the practice of surgery because it was too base and manual. [1]

In medieval Europe, medicinal herbs and plants were cultivated in monastery and nunnery gardens beginning about the eighth century. Charlemagne gave orders for the collection of medicinal plants to systematically grown in his royal garden. This royal garden was an important precedent for botanical gardens and physic gardens that were established in the sixteenth century. It was also the beginning of the study botany as a separate discipline. In about the twelfth century, medicine and pharmacy began to be taught in universities. [3]

Shabbethai Ben Abraham, better known as Shabbethai Donnolo, (913-c 982), was a ninth century Italian Jew and the author of an early Hebrew text, Antidotarium. It consisted of detailed drugs descriptions, medicinal remedies, practical methods for preparing medicine from roots. It was a veritable glossary of herbs and drugs used during the medieval period. Donnollo was widely traveled and collected information from Arabic, Greek and Roman sources. [1]

In the Dark and Middle Ages Nestorian Christians were banished for their heretical views that they carried to Asia Minor. The Greek text was translated into Syriac when pagan Greek scholars fled east after Constantine’s conquest of Byzantium, Stephanos (son of Basilios, a Christian living in Baghdad under the Khalif Motawakki) made an Arabic translation of De Materia Medica from the Greek in 854CE. In 948CE the Byzantine Emperor Romanus II, son and co-regent of Constantine [Porphyrogenitos]], sent a beautifully illustrated Greek manuscript of De Materia Medica to the Spanish Khalif, Abd-Arrahman III. Later The Syriac scholar Bar Hebraeus prepared an illustrated Syriac version in 1250, which was translated into Arabic.[12][13][6]

Modern Age

Matthaeus Silvaticus, Avicenna, Galen, Dioscorides ,Platearius and Serapio, inspired the appearance of 3 main works printed in Mainz: In 1484 The Herbarius, the following year The Gart der Gesundheit , and in 1491 the Ortus Sanistatus. The works contain 16, 242 and 570 references to Dioscorides, respectively.[8]

The 1st appearance of Dioscorides as a printed book was a Latin translation printed at Colle, Italy by Johanemm Allemanun de Mdemblik in 1478. Jean Ruel perfected this translation, which became very popular. From this point, Latin was the preferred language for presenting De Materia Medica.

The greek version appeared in 1499 by Manutius at Venice. The most useful books of botany used by students and scholars were supplemented commentaries on Dioscorides, including the works of Fuchs, Anguillara, Mattioli,Maranta, Cesalpino, Dodoens, Fabius Columna, Gaspard Bauhin& Johann Bauhin, and De Villanueva/Servetus. In several of these versions, the annotations and comments exceed the Dioscoridean text and have much new botany. Printers were not merely printing the authentic Materia Medica, but hiring experts on the medical and botanical field for criticism, commentaries, that would raise the stature of the printers and the work.

The greek version was reprinted in 1518,1523 and 1529, and reprinted in 1518, 1523 and 1529. Between 1555 and 1752 there were at least twelve Spanish editions; and as many in Italian from 1542. French editions appeared from 1553; and German editions from 1546.[6][3]

See also

- Physic Garden

- Chelsea Physic Garden

- Botanical Garden

- Theriac

- Herbal

Notes

- ^ a b c Le Wall, Charles. The Curious Lore of Drugs and Medicines: Four Thousand Years of Pharmacy. (Garden City, New York: Garden City Publishing Co. Inc: 1927)

- ^ a b Parker, Linette A. "A Brief History of Materia Medica," in The American Journal of Nursing, Vol.15, No. 8 (May 1915). pp 650-653.

- ^ a b c Le Wall, Charles. The Curious Lore of Drugs and Medicines: Four Thousand Years of Pharmacy. (Garden City, New York: Garden City Publishing Co. Inc: 1927) and Riddle, John M.Dioscorides on pharmacy and medicine. (Austin: University of Texas Press,1985)

- ^ Findlen, Paula. Possessing Nature: Museums, Collecting, and Early Scientific Culture in Early Modern Italy. (Berkeley, Los Angeles, & London: University of California Press, 1994): 241.

- ^ Le Wall, Charles. The Curious Lore of Drugs and Medicines: Four Thousand Years of Pharmacy. (Garden City, New York: Garden City Publishing Co. Inc: 1927) and Parker, Linette A. "A Brief History of Materia Medica," in The American Journal of Nursing, Vol.15, No. 9 (June 1915). pp 729-734.

- ^ a b c Osbaldeston, Tess Anne Dioscorides(Ibidis Press,2000)

- ^ Collins, Minta. Medieval Herbals: The Illustrative Traditions. (London: The British Library and University of Toronto Press, 2000): 32.

- ^ a b Parker, Linette A. "A Brief History of Materia Medica," in The American Journal of Nursing, Vol.15, No. 9 (June 1915). pp 729-734 and Riddle, John M. Dioscorides on pharmacy and medicine. (Austin: University of Texas Press,1985)

- ^ Fahd, Toufic, "Botany and agriculture", p. 815, in (Morelon & Rashed 1996, pp. 813–52)

- ^ Diane Boulanger (2002), "The Islamic Contribution to Science, Mathematics and Technology", OISE Papers, in STSE Education, Vol. 3.

- ^ Huff, Toby (2003), The Rise of Early Modern Science: Islam, China, and the West, Cambridge University Press, p. 218, ISBN 0521529948, OCLC 50730734

- ^ Karlikata,E.:Dioscorides ve Materia Medica(Kitab'ül Hasayis). Olusum yil 7 Sayi 28 (1999) 50.

- ^ Sonneddecker,G. Kremers and Urdang's history of Pharmacy,3rd edition,Lipincott Company, America 1963 p15)

References

- Morelon, Régis; Rashed, Roshdi (1996), Encyclopedia of the History of Arabic Science, 3, Routledge, ISBN 0415124107

Categories:

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.