- Oreochromis mossambicus

-

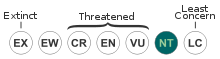

Mozambique Tilapia Conservation status Scientific classification Kingdom: Animalia Phylum: Chordata Class: Actinopterygii Order: Perciformes Family: Cichlidae Subfamily: Pseudocrenilabrinae Tribe: Tilapiini Genus: Oreochromis Species: O. mossambicus Binomial name Oreochromis mossambicus

(Peters, 1852)The Mozambique tilapia, Oreochromis mossambicus, is a tilapiine cichlid fish native to southern Africa. It is a popular fish for aquaculture. It is now found in tropical and subtropical habitats around the globe, where it can become an invasive species.

Contents

Morphology

The Mozambique tilapia is laterally compressed, and has a deep body with long dorsal fins, the front part of which has spines. Coloration is typically yellow, although this is variable, and there may be weak banding.

Home Range

The Mozambique tilapia is native to coastal regions and the lower reaches of rivers in southern Africa, from the Zambezi River delta to Bushman River in the eastern Cape.[1] It is threatened in its home range by competition with the invasive Nile tilapia (Waal 2002).

Diet

Mozambique tilapia are omnivorous. They can consume detrital material, diatoms, invertebrates, small fry and vegetation ranging from macroalgae to rooted plants (Mook 1983, Trewevas 1983). This broad diet helps the species thrive in diverse locations.

Invasiveness

The Mozambique tilapia is an invasive species in many parts of the world, having escaped from aquaculture or been deliberately introduced to control mosquitoes (Moyle 1976). It has been nominated by the Invasive Species Specialist Group (ISSG) as one the 100 worst invasive species in the world (Courtenay 1989). It can harm native fish populations through competition for food and nesting space, as well as by directly consuming small fish (Courtenay et al. 1974). In Hawaii, striped mullet Mugil cephalus are threatened because of the introduction of this species. Mozambique tilapia may also be responsible for the decline of the desert pupfish, Cyprinodon macularius, in California's Salton Sea (Courtenay and Robins 1989, Swift et al. 1993).

Hybridization

As with most species of tilapia, Mozambique tilapia have a high potential for hybridization. They are often crossbred with other tilapia species in aquaculture because purebred Mozambique tilapia grow slowly and have a body shape poorly suited to cutting large fillets. Also, hybrids between certain parent combinations (such as between Mozambique and Wami tilapia) result in offspring that are all or predominantly male. Male tilapia are preferred in aquaculture as they grow faster and have a more uniform adult size than females. The "Florida Red" tilapia is popular commercial hybrid of Mozambique and Blue tilapia.[2]

Reproduction

In the first step in the reproductive cycle for Mozambique tilapia, males excavate a nest into which a female can lay her eggs. After the eggs are laid the male fertilizes them. Then the female stores the eggs in her mouth, called mouthbrooding, until the fry hatch (Popma, 1999).

Use in aquaculture

Mozambique tilapia are hardy individuals that are easy to raise and harvest, making them a good aquacultural species. They have a mild, white flesh that is appealing to consumers. This species constitutes about 4% of the total tilapia aquaculture production worldwide, but is more commonly hybridized with other tilapia species (Gupta and Acosta 2004). Tilapia are very susceptible to diseases such as whirling disease and ich (Popma, 1999).

Other names

The species is known by a number of other names including

- Oreochromis andersonii

- Tilapia kafuensis

- Kafue bream

- Three spotted tilapia

References

- Froese, Rainer, and Daniel Pauly, eds. (2007). "Oreochromis mossambicus" in FishBase. 2 2007 version.

- "Oreochromis mossambicus". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. http://www.itis.gov/servlet/SingleRpt/SingleRpt?search_topic=TSN&search_value=170015. Retrieved 10 January 2007.

- Courtenay W.R., Jr. 1989. Exotic fishes in the National Park System. Pages 237-252 in: Thomas L.K. (Ed) . Proceedings of the 1986 conference on science in the national parks, volume 5. Management of exotic species in natural communities. U.S. National Park Service and George Wright Society, Washington, DC.

- Courtenay W.R., Jr., and C.R. Robins. 1989. Fish introductions: Good management, mismanagement, or no management? CRC Critical Reviews in Aquatic Sciences 1:159-172.

- Courtenay W.R., Jr., Sahlman H.F, Miley W.W., II, and D.J. Herrema. 1974. Exotic fishes in fresh and brackish waters of Florida. Biological Conservation 6:292-302.

- Gupta M.V. and B.O. Acosta. 2004. A review of global tilapia farming practices. WorldFish Center P.O. Box 500 GPO, 10670, Penang, Malaysia.

- Mook D. 1983. Responses of common fouling organisms in the Indian River, Florida, to various predation and disturbance intensities. Estuaries 6:372-379.

- Moyle P.B. 1976. Inland fishes of California. University of California Press, Berkeley, CA. 330 p.

- Popma, T. Tilapia Life History and Biology 1999 Southern Region Aquaculture Center

- Swift C.C., Haglund T.R., Ruiz M., and R.N. Fisher. 1993. The status and distribution of the freshwater fishes of southern California. Bulletin of the Southern California Academy of Science 92:101-167.

- Trewevas E. 1983. Tilapiine Fishes Of The Genera Sarotherodon, Oreochromis And Danakilia. British Museum Of Natural History, Publication Number 878.Comstock Publishing Associates. Ithaca, New York. 583 p.

- Waal, Ben van der, 2002. Another fish on its way to extinction?. Science in Africa.

External links

- Photo of "Florida Red" hybrid. Retrieved 2007-JUL-12.

Categories:- IUCN Red List near threatened species

- Oreochromis

- Fish of Africa

- Animals described in 1852

- Near threatened animals

- Invasive fish species

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.