- Contrast effect

-

A contrast effect is the enhancement or diminishment, relative to normal, of perception, cognition and related performance as a result of immediately previous or simultaneous exposure to a stimulus of lesser or greater value in the same dimension. (Here, normal perception or performance is that which would be obtained in the absence of the comparison stimulus—i.e., one based on all previous experience.)

Contrast effects are ubiquitous throughout human and non-human animal perception, cognition, and resultant performance. A hefted weight is perceived as heavier than normal when "contrasted" with a lighter weight. It is perceived as lighter than normal when contrasted with a heavier weight. An animal works harder than normal for a given amount of reward when that amount is contrasted with a lesser amount and works less energetically for that given amount when it is contrasted with a greater amount. A person appears more appealing than normal when contrasted with a person of less appeal and less appealing than normal when contrasted with one of greater appeal.

Contents

Types

Simultaneous contrast identified by Michel Eugène Chevreul refers to the manner in which the colors of two different objects affect each other. The effect is more noticeable when shared between objects of complementary color.[1]

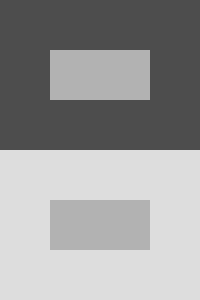

In the image here, the two inner rectangles are exactly the same shade of grey, but the upper one appears to be a lighter grey than the lower one due to the background provided by the outer rectangles.

This is a different concept from contrast, which by itself refers to one object's difference in color and luminance compared to its surroundings or background.

Successive contrast occurs when the perception of currently viewed stimuli is modulated by previously viewed stimuli.

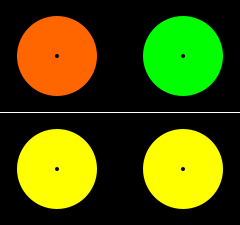

For example, when one stares at the dot in the center of one of the two colored disks on the top row for a few seconds and then looks at the dot in the center of the disk on the same side in the bottom row, the two lower disks, though identically colored, appear to have different colors for a few moments.

One type of contrast that involves both time and space is metacontrast and paracontrast. When one half of a circle is lit for 10 milliseconds, it is at its maximum intensity. If the other half is displayed at the same time (but 20-50 ms later), there is a mutual inhibition: the left side is darkened by the right half (metacontrast), and the center may be completely obliterated. At the same time, there is a slight darkening of the right side due to the first stimulus; this is paracontrast.[2]

Metacontrast and paracontrast

Metacontrast and paracontrastDomains

The contrast effect was noted by the 17th Century philosopher John Locke, who observed that lukewarm water can feel hot or cold, depending on whether the hand touching it was previously in hot or cold water.[3] In the early 20th Century, Wilhelm Wundt identified contrast as a fundamental principle of perception, and since then the effect has been confirmed in many different areas.[3] Contrast effects shape not only visual qualities like color and brightness, but other kinds of perception, including the perception of weight.[4] One experiment found that thinking of the name "Hitler" led to subjects rating a person as more friendly.[5] Whether a piece of music is perceived as good or bad can depend on whether the music heard before it was unpleasant or pleasant.[6] For the effect to work, the objects being compared need to be similar to each other: a television reporter can seem to shrink when interviewing a tall basketball player, but not when standing next to a tall building.[4]

See also

References

- ^ Colour, Why the World Isn't Grey, Hazel Rosotti, Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ, 1985, pp 135-136. ISBN 0-691-02386-7

- ^ "eye, human."Encyclopædia Britannica. 2008. Encyclopædia Britannica 2006 Ultimate Reference Suite DVD

- ^ a b Kushner, Laura H. (2008). Contrast in judgments of mental health. ProQuest. p. 1. ISBN 9780549913146. http://books.google.com/books?id=TYn5VHp9jioC&pg=PA1. Retrieved 24 March 2011.

- ^ a b Plous, Scott (1993). The psychology of judgment and decision making. McGraw-Hill. pp. 38–41. ISBN 9780070504776. http://books.google.com/books?id=xvWOQgAACAAJ. Retrieved 24 March 2011.

- ^ Moskowitz, Gordon B. (2005). Social cognition: understanding self and others. Guilford Press. p. 421. ISBN 9781593850852. http://books.google.com/books?id=_-NLW8Ynvp8C&pg=PA421. Retrieved 24 March 2011.

- ^ Popper, Arthur N. (30 November 2010). Music Perception. Springer. p. 150. ISBN 9781441961136. http://books.google.com/books?id=ZYXd3CF1_vkC&pg=PA150. Retrieved 24 March 2011.

External links

Categories:- Perception

- Cognition

- Cognitive biases

- Vision

- Psychophysics

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.