- Christine de Pizan

-

Christine de Pizan

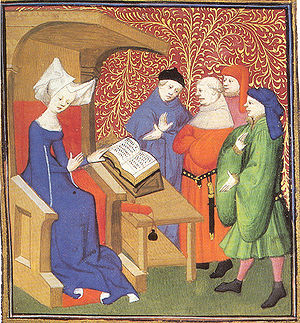

Christine de Pizan lecturing men.Born 11 September 1363

VeniceDied c. 1430 (aged 65–66) Christine de Pizan (also seen as de Pisan) (1363 – c. 1430) was a Venetian-born late medieval author who challenged misogyny and stereotypes prevalent in the male-dominated medieval culture. As a poet, she was well known and highly regarded in her own day; she completed 41 works during her 30 year career (1399–1429), and can be regarded as Europe’s first professional woman writer.[1] She married in 1380, at the age of 15 and was widowed 10 years later. Much of the impetus for her writing came from her need to earn a living for herself and her three children. She spent most of her childhood and all of her adult life based in Paris and then the abbey at Poissy, and wrote entirely in her adoptive tongue of Middle French.

Her early courtly poetry is marked by her knowledge of aristocratic custom and fashion of the day, particularly involving women and the practice of chivalry. Her early and later allegorical and didactic treatises reflect both autobiographical information about her life and views and also her own individualized and protofeminist approach to the scholastic learned tradition of mythology, legend, and history she inherited from clerical scholars and to the genres and courtly or scholastic subjects of contemporary French and Italian poets she admired. Supported and encouraged by important royal French and English patrons, Christine had a influenced fifteenth-century English poetry. Her success stems from a wide range of innovative writing and rhetorical techniques that critically challenged renowned male writers, such as Jean de Meun who incorporated misogynist beliefs within their literary works.

In recent decades, Christine's work has been returned to prominence by the efforts of scholars such as Charity Cannon Willard, Earl Jeffrey Richards and Simone de Beauvoir. Certain scholars have argued that she should be seen as an early feminist who efficiently used language to convey that women could play an important role within society. This characterization has been challenged by other critics who claim either that it is an anachronistic use of the word, or that her beliefs were not progressive enough to merit such a designation.[2]

Contents

Life

French literature By category French literary history French writers Chronological list

Writers by category

Novelists · Playwrights

Poets · Essayists

Short story writersPortals France · Literature Christine de Pizan was born in 1363 in Venice. She was the daughter of Tommaso di Benvenuto da Pizzano (Thomas de Pizan; named for the family's origins in the town of Pizzano, south east of Bologna), a physician, court astrologer, and Councillor of the Republic of Venice.[3] Following Christine’s birth, Thomas de Pizan accepted an appointment to the court of Charles V of France, as the king’s astrologer, alchemist, and physician. In this atmosphere, Christine was able to pursue her intellectual interests. She successfully educated herself by immersing herself in languages, in the rediscovered classics and humanism of the early Renaissance, and in Charles V’s royal archive that housed a vast number of manuscripts. Pizan did not assert her intellectual abilities, or establish her authority as a writer until she was widowed at the age of twenty-four.[4]

Christine de Pizan married Etienne du Castel, a royal secretary to the court, at the age of fifteen. She had three children, a daughter (who went to live at the Dominican Abbey in Poissy in 1397 as a companion to the king's daughter, Marie), a son Jean, and another child who died in childhood.[5] Christine’s familial life was threatened in 1390 when her husband, while in Beauvais on a mission with the king, suddenly died in an epidemic.[6] Following Castel’s death, Christine was left to support her mother, a niece, and her two children.[7] When she tried to collect money from her husband’s estate, she faced complicated lawsuits regarding the recovery of salary due to her husband.[6] In order to support herself and her family, Christine turned to writing. By 1393, she was writing love ballads, which caught the attention of wealthy patrons within the court. These patrons were intrigued by the novelty of a female writer and had her compose texts about their romantic exploits.[8] Christine's output during this period was prolific. Between 1393 and 1412, she composed over three hundred ballads, and many more shorter poems.

Christine de Pizan’s participation in a literary quarrel, in 1401–1402, allowed her to move beyond the courtly circles, and ultimately to establish her status as a writer concerned with the position of women in society. During these years, she involved herself in a renowned literary debate, the “Querelle du Roman de la Rose”.[9] Christine helped to instigate this debate by beginning to question the literary merits of Jean de Meun’s the Romance of the Rose. Written in the thirteenth century, the Romance of the Rose satirizes the conventions of courtly love while critically depicting women as nothing more than seducers. Christine specifically objected to the use of vulgar terms in Jean de Meun’s allegorical poem. She argued that these terms denigrated the proper and natural function of sexuality, and that such language was inappropriate for female characters such as Madame Raison. According to Christine, noble women did not use such language.[10] Her critique primarily stems from her belief that Jean de Meun was purposely slandering women through the debated text.

The debate itself is extensive and at its end, the principal issue was no longer Jean de Meun’s literary capabilities. The principal issue had shifted to the unjust slander of women within literary texts. This dispute helped to establish Christine’s reputation as a female intellectual who could assert herself effectively and defend her claims in the male-dominated literary realm. Christine continued to counter abusive literary treatments of women.

Works

By 1405, Christine de Pizan had completed her most successful literary works, The Book of the City of Ladies and The Treasure of the City of Ladies, or The Book of the Three Virtues. The first of these shows the importance of women’s past contributions to society, and the second strives to teach women of all estates how to cultivate useful qualities in order to counteract the growth of misogyny (Willard 1984:135).

Christine’s final work was a poem eulogizing Joan of Arc, the peasant girl who took a very public role in organizing French military resistance to English domination in the early fifteenth century. Written in 1429, The Tale of Joan of Arc celebrates the appearance of a woman military leader who, according to Christine, vindicated and rewarded all women’s efforts to defend their own sex (Willard 1984:205). Besides its literary qualities, this poem is important to historians because it is the only record of Joan of Arc outside the documents of her trial. After completing this particular poem, it seems that Christine, at the age of sixty-five, decided to end her literary career (Willard 1984:207). The exact date of her death is unknown. However, her death did not diminish appreciation for her renowned literary works. Instead, her legacy continued on because of the voice she established as an authoritative rhetorician.

In the “Querelle du Roman de la Rose,” Christine responded to Jean de Montreuil, who had written her a treatise defending the misogynist sentiments in the Romance of the Rose. She begins by claiming that her opponent was an “expert in rhetoric” as compared to herself “a woman ignorant of subtle understanding and agile sentiment.” In this particular apologetic response, Christine belittles her own style. She is employing a rhetorical strategy by writing against the grain of her meaning, also known as antiphrasis (Redfern 80). Her ability to employ rhetorical strategies continued when Christine began to compose literary texts following the “Querelle du Roman de la Rose.”

In The Book of the City of Ladies Christine de Pizan created a symbolic city in which women are appreciated and defended. Christine, having no female literary tradition to call upon, constructs three allegorical foremothers: Reason, Justice, and Rectitude. She enters into a dialogue, a movement between question and answer, with these allegorical figures that is from a completely female perspective (Campbell 6). These constructed women lift Christine up from her despair over the misogyny prevalent in her time. Together, they create a forum to speak on issues of consequence to all women. Only female voices, examples and opinions provide evidence within this text. Christine, through Lady Reason in particular, argues that stereotypes of woman can be sustained only if women are prevented from entering the dominant male-oriented conversation (Campbell 7). Overall, Christine hoped to establish truths about women that contradicted the negative stereotypes that she had identified in previous literature. She did this successfully by creating literary foremothers that helped her to formulate a female dialogue that celebrated women and their accomplishments.

In The Treasure of the City of Ladies, Christine highlights the persuasive effect of women’s speech and actions in everyday life. In this particular text, Christine argues that women must recognize and promote their ability to make peace. This ability will allow women to mediate between husband and subjects. She also claims that slanderous speech erodes one’s honor and threatens the sisterly bond among women. Christine then argues that "skill in discourse should be a part of every woman’s moral repertoire" (Redfern 87). Christine understood that a woman’s influence is realized when her speech accords value to chastity, virtue, and restraint. She proved that rhetoric is a powerful tool that women could employ to settle differences and to assert themselves. Overall, she presented a concrete strategy that allowed all women, regardless of their status, to undermine the dominant patriarchal discourse. For the general reader the Treasure is appealing because she gives fascinating glimpses into women's lives in 1400, from the great lady in the castle down to the merchant's wife, the servant, and the peasant. She offers advice to governesses, widows, and even prostitutes.

Christine specifically sought out other women to collaborate in the creation of her work. She makes special mention of a manuscript illuminator we know only as Anastasia who she described as the most talented of her day.[11]

Influence

Christine de Pizan contributed to the rhetorical tradition by counteracting the contemporary discourse. Rhetorical scholars have studied her persuasive strategies. It has been concluded that Christine successfully forged a rhetorical identity for herself, and encouraged women to embrace this identity by counteracting misogynist thinking through persuasive dialogue.[12] Simone de Beauvoir wrote in 1949 that Épître au Dieu d'Amour was "the first time we see a woman take up her pen in defense of her sex" making Christine de Pizan perhaps the West's first feminist, or protofeminist as some scholars prefer to say.[13][14]

Selected bibliography

- L'Épistre au Dieu d'amours (1399)

- L'Épistre de Othéa a Hector (1399–1400)

- Dit de la Rose (1402)

- Cent Ballades d'Amant et de Dame, Virelyas, Rondeaux (1402)

- Le Chemin de long estude (1403)

- Livre de la mutation de fortune (1403)

- La Pastoure (1403)

- Le Livre des fais et bonners meurs du sage roy Charles V (1404)

- Le Livre de la cité des dames (1405)

- Le Livre des trois vertus (1405)

- L'Avision de Christine (1405)

- Livre du corps de policie (1407)

- Livre de paix (1413)

- Ditié de Jehanne d'Arc (1429)

Contemporary scholarship

- The standard translation of The Book of the City of Ladies is by Earl Jeffrey Richards, (1982). The first English translation of Christine de Pizan’s The Treasure of the City of Ladies: or The Book of the Three Virtues is Sarah Lawson’s (1985).

- The standard biography about Christine de Pizan is Charity Cannon Willard’s Christine de Pisan: Her Life and Works (1984). Willard’s biography also provides a comprehensive overview of the “Querelle du Roman de la Rose.” Kevin Brownlee also discusses this debate in detail in his article Widowhood, Sexuality and Gender in Christine de Pisan (in The Romanic Review, 1995)

- For a more detailed account of Christine de Pizan’s rhetorical strategies refer to Jenny R. Redfern’s excerpt Christine de Pisan and The Treasure of the City of Ladies: A Medieval Rhetorician and Her Rhetoric (in Reclaiming Rhetorica, ed. Andrea A. Lunsford, 1995).

- M. Bell Mirabella discusses Christine’s ability to refute the patriarchal discourse in her article Feminist Self-Fashioning: Christine de Pisan and The Treasure of the City of Ladies (in The European Journal of Women’s Studies, 1999).

- Karlyn Kohrs Campbell presents an interesting argument about Christine’s ability to create a female-oriented dialogue in her lecture Three Tall Women: Radical Challenges to Criticism, Pedagogy, and Theory (The Carroll C. Arnold Distinguished Lecture, National Communication Association, 2001).

- Refer to The Rhetorical Tradition (ed. Patricia Bizzell and Bruce Herzberg, 2001) and The Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism (ed. Vincent B. Leitch, 2001) for some commentary on Christine de Pizan’s life, literary works, rhetorical contributions and other relevant sources that one may find useful.

See also

- Isabeau of Bavaria

- Joan of Arc

- List of French language poets

- Vernacular literature

- Women's history

- Antoine Vérard

Notes

- ^ Jenny Redfern, "Christine de Pisan and The Treasure of the City of Ladies: A Medieval Rhetorician and Her Rhetoric" in Lunsford, Andrea A, ed. Reclaiming Rhetorica: Women and in the Rhetorical Tradition(Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1995), p. 74

- ^ Earl Jeffrey Richards, ed, Reinterpreting Christine de Pizan (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 1992), pp. 1-2.

- ^ Christine de Pizan, The Book of the City of Ladies, trans. by Rosalind Brown-Grant (London: Penguin Books, 1999), introduction.

- ^ Redfern, p. 76.

- ^ Charity C. Willard, Christine de Pizan: Her Life and Works (New York: Persea Books, 1984), p. 35.

- ^ a b Willard, p. 39.

- ^ Pizan, ed. by Brown-Grant, introduction.

- ^ Redfern, p. 77.

- ^ Willard, p. 73.

- ^ Maureen Quilligan, The Allegory of Female Authority: Christine de Pizan's "Cité des Dames" (New York: Cornell University Press, 1991), p. 40.

- ^ Christine de Pizan: An illuminated Voice By Doré Ripley, 2004 Accessed October 2007

- ^ Needs Reference

- ^ de Beauvoir, Simone, English translation 1953 (1989). The Second Sex. Vintage Books. pp. 105. ISBN 0-679-72451-6.

- ^ Schneir, Miram, 1972 (1994). Feminism: The Essential Historical Writings. Vintage Books. p. xiv. ISBN 0-679-75381-8.

References

- Altmann, Barbara K., and Deborah L. McGrady, eds. Christine de Pizan: A Casebook. New York: Routledge, 2003.

- Altmann, Barbara K., "Christine de Pizan as Maker of the Middle Ages," in: Cahier Calin: Makers of the Middle Ages. Essays in Honor of William Calin, ed. Richard Utz and Elizabeth Emery (Kalamazoo, MI: Studies in Medievalism, 2011), pp. 30-32.

- Brown-Grant, Rosalind., Christine de Pizan and the Moral Defence of Women: Reading beyond Gender. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

- Brown-Grant, Rosalind. trans. and ed. Christine de Pizan. The Book of the City of Ladies. Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin Books, 1999.

- Campbell, Karlyn K., Three Tall Women: Radical Challenges to Criticism, Pedagogy, and Theory, The Carroll C. Arnold Distinguished Lecture National Communication Association November 2001 Boston: Pearson Education Inc, 2003.

- Fenster, Thelma S., and Nadia Margolis, eds. and trans. Christine de Pizan, The Book of the Duke of True Lovers. New York: Persea, 1991.

- Green, Karen, and Constant J. Mews, eds. Healing the Body Politic: The Political Thought of Christine de Pizan, Turnhout, Belgium: Brepols, 2005.

- Green, Karen, Constant J. Mews, and Janice Pinder, eds. The Book of Peace by Christine de Pizan.University Park: Penn State Press, 2008.

- Kosta-Théfaine, Jean-François. La Poétesse et la guerrière : Lecture du 'Ditié de Jehanne d'Arc' de Christine de Pizan. Lille: TheBookEdition, 2008. Pp. 108.

- Mathilde Laigle, Le livre des trois vertus de Christine de Pisan et son milieu historique et littéraire, Paris, Honoré Champion, 1912, 375 pages, collection : Bibliothèque du XVe siècle siècle (this book is the translation of an American thesis of Mathilde Laigle, Columbia U.)

- Margolis, Nadia, An Introduction to Christine de Pizan. New Perspectives in Medieval Literature, 1. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2011.

- Quilligan, Maureen, The Allegory of Female Authority: Christine de Pizan's "Cité des Dames". New York: Cornell University Press, 1991.

- Reno, Christine, and Liliane Dulac, eds. Le Livre de l’Advision Cristine. Études christiniennes, 4. Paris: Champion, 2000.

- Richards, Earl Jeffrey, ed., Reinterpreting Christine de Pizan, Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 1992.

- Richards, Earl Jeffrey, ed. and trans. Christine de Pizan, The Book of the City of Ladies. Intro. by Natalie Zemon Davis. Rev. ed. New York: Persea, 1998.

- Redfern, Jenny, "Christine de Pisan and The Treasure of the City of Ladies: A Medieval Rhetorician and Her Rhetoric" in Lunsford, Andrea A, ed. Reclaiming Rhetorica: Women and in the Rhetorical Tradition, Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1995.

- Willard, Charity C., ed, The "Livre de Paix" of Christine de Pisan: A Critical Edition, The Hague: Mouton, 1958. (now superseded by Green, et al. ed., see above).

- Willard, Charity C., Christine de Pizan: Her Life and Works. New York: Persea Books, 1984

Further reading

- Angus J. Kennedy's "Christine de Pizan: A Bibliographical Guide and supplements (London: Grant & Cutler, 1984, 1994, 2004).

External links

- Ditie de Jehanne d'Arc - French w/ English translation

- Works by Christine de Pisan at Project Gutenberg

- Comprehensive bibliography of her works, including listings of the manuscripts, editions, translations, and essays. in French at Archives de littérature du Moyen Âge (Arlima)

- '"A Champion of Her Sex", W. Minto in Macmillan's Magazine, Volume LXIII, Nov. 1885 - Apr. 1886, pp. 264–275

- The Song of Joan of Arc poem - English translation w/ original French

Categories:- 1363 births

- 1430 deaths

- French poets

- Medieval poets

- Women of medieval France

- People from Venice (city)

- Rhetoricians

- 14th-century women writers

- 15th-century women writers

- French women writers

- 14th-century French writers

- 15th-century French writers

- Feminism and history

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.