- Miss Lonelyhearts

-

Miss Lonelyhearts

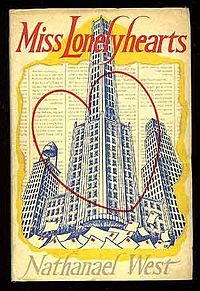

1949 first UK edition coverAuthor(s) Nathanael West Country United States Language English Publisher Liveright Publication date April 8, 1933 Media type Print, Hardcover, Paperback Miss Lonelyhearts, published in 1933, is Nathanael West's second novel. It is an Expressionist black comedy set in New York City during the Great Depression.

Contents

Plot summary

In the story, Miss Lonelyhearts is an unnamed male newspaper columnist writing an advice column which the newspaper staff considers a joke. As Miss Lonelyhearts reads letters from desperate New Yorkers, he feels terribly burdened and falls into a cycle of deep depression, accompanied by heavy drinking and occasional bar fights. He is also the victim of the pranks and cynical advice of his feature editor at the newspaper, "Shrike" (a type of predatory bird).

Miss Lonelyhearts tries several approaches to escape the terribly painful letters he has to read through religion, trips to the countryside with his fiancee Betty, and affairs with Shrike's wife and Mrs. Doyle, a reader of his column. However, Miss Lonelyhearts' efforts do not seem to ameliorate his situation. After his sexual encounter with Mrs. Doyle, he meets her husband, a poor crippled man. The Doyles invite Miss Lonelyhearts to have dinner with them. When he arrives, Mrs. Doyle tries to seduce him again, but he responds by beating her. Mrs. Doyle tells her husband that Miss Lonelyhearts tried to rape her.

In the last scene, Mr. Doyle hides a gun inside a rolled newspaper and decides to take revenge on Miss Lonelyhearts, who has just experienced a religious enlightenment after three days of sickness and runs toward Mr. Doyle to embrace him. The gun "explodes," and the two men roll down a flight of stairs together.

Major themes

The general tone of the novel is one of extreme disillusionment with Depression-era American society, a consistent theme throughout West's novels. However, the novel is a black comedy, characterized by a dark sense of humor and irony. Justus Neiland,[1] among others, has pointed out the use of Bergsonian laughter, in which “the attitudes, gestures, and movements of the human body are laughable in exact proportion as that body reminds us of a machine.” [2]

The novel can be read as a condemnation of alienation and the colonization of social life by commodification, foreshadowing the stance of the Situationists and Guy Debord in particular. Miss Lonelyhearts is unable to fulfill his role as advice giver in a world in which both people and advice (in the form of newspaper ads, for example) are mass produced. People are machines for the sole purpose of laboring as far as the rest of society is concerned (thus Miss Lonelyhearts' name), and any advice for them is as mass produced as a manual for a machine. Lonelyhearts is unable to find a personal solution to his problems because they have systemic causes. West, who worked in the newspaper business before writing Miss Lonelyhearts, is also an advice giver of a sort as a novelist. Miss Lonelyhearts is similar to a détournement because it uses a form to critique the same form. The novel also condemns itself by condemning art, which is repeatedly derided by Shrike and compared to religion as an opiate of the masses.[3][4]

Alternatively, the novel can be treated as a meditation on the theme of theodicy, or the problem of why evil exists in the world. The novel's protagonist is psychologically and "spiritually" overwhelmed by his perception of Evil. He then tries different approaches to tackle this question (religion, logic, love, existentialism) but they are all ultimately proven inadequate.[citation needed]

Many of the problems described in Miss Lonelyhearts describe actual economic conditions in New York City during the Great Depression, although the novel carefully avoids questions of national politics. Moreover, the novel is particularly important due to its existential import. The characters seem to be living in an amoral world. Hence, they resort to heavy drinking, sex, and parties. Miss Lonelyhearts has a "Christ complex", which stands for his belief in religion as a solution to a world devoid of values. However, he approaches the status of an absurd hero insofar as his religious convictions further his depression and disillusionment. Ironically, he is shot at the moment he thinks he has had a religious conversion.[citation needed]

Film, TV or theatrical adaptations

1933 film

In 1933, the novel was very loosely adapted as a movie, Advice to the Lovelorn, starring Lee Tracy, produced by 20th Century Pictures -- before its merger with Fox Film Corporation -- and released by United Artists. Greatly changed from the novel, it became a comedy/drama about a hard-boiled reporter who becomes popular when he adopts a female pseudonym and dispenses fatuous advice. He agrees (for a hefty payment) to use the column to recommend a line of medicines, but finds out they are actually harmful drugs when his mother dies. He then agrees to help the police track down the criminals. The movie ends with the main character happily married.

Broadway

In 1957, the novel was adapted into a stage play entitled Miss Lonelyhearts by Howard Teichmann. It opened on Broadway at the Music Box Theatre on October 3, 1957 in a production directed by Alan Schneider and designed by Jo Mielziner and Patricia Zipprodt. It ran for only twelve performances.

1958 film

- Main article, see Lonelyhearts

In 1958 the plot was again filmed as Lonelyhearts, starring Montgomery Clift, Robert Ryan, and Myrna Loy, produced by Dore Schary and released by United Artists. Although following the plot of the book more closely than Advice to the Lovelorn, many changes were made. The movie greatly softens the cynical edge of the original book, and the story is once more given a happy ending—the woman's husband is talked out of shooting Miss Lonelyhearts, who finds happiness with his true love, and Shrike is considerably nicer at film's end. It was filmed once more in 1983 as Miss Lonelyhearts, again undercutting the cynicism by making the author a figure of pathos.

1983 film

The film was adapted by Michael Dinner into a 1983 TV movie starring Eric Roberts in the lead role. Eric Roberts would coincidentally play the lead role in the unrelated 1991 film Lonely Hearts.

2006 opera

In 2006, composer Lowell Liebermann completed Miss Lonelyhearts, a two-act opera. The libretto was written by J. D. McClatchy. The opera, which received its premiere April 26, 28, and 30, 2006 at the Juilliard Opera Center, was commissioned by the Juilliard School for its centennial celebration. The opera was co-commissioned by two other schools: USC's Thornton School of Music as well as the University of Cincinnati College-Conservatory of Music.

The opera was co-produced by the Thornton School of Music Opera Program at University of Southern California, and received its West Coast Premiere at the school on April 20–22, 2007. Both premieres were directed by renowned stage director and Thornton faculty member Ken Cazan. Liebermann and McClatchy cleaned up a few bits of the score for this performance, having seen what needed work the preceding year.

In other literary works

Miss Lonelyhearts plays an important role, as it is not just cited, but discussed by two of the characters of Philip K. Dick's The Man in the High Castle, Paul Kasoura and Robert Childan. Given that the eponymous Miss Lonelyhearts and his fellow protagonists are struggling for existential meaning and interpersonal relationships in the uncertain, threatening sociopolitical context of the Great Depression, Dick may have intended this citation as a parallel narrative to the similar alienation, existential and interpersonal crises of his own protagonists in a world on the brink of Nazi-Japanese nuclear war after the Axis won World War II in its alternative universe (and, as an ironic contrast, our own). As such, it can be seen as a mise en abyme reference in terms of its underlying narrative structure.

Notes

- ^ Nieland, Justus. “West's Deadpan: Affect, Slapstick, and Publicity in Miss Lonelyhearts.” Novel 38.1 (2004): 57-85.

- ^ Bergson, Henri. “Laughter.” Comedy: An Essay on Comedy, Laughter. Ed. Wylie Sypher. New York: Doubleday, 1956. 61-190.

- ^ Barnard, Rita. "The Storyteller, the Novelist, and the Advice Columnist: Narrative and Mass Culture in Miss Lonelyhearts.” Novel 27.1 (1993): 40-61.

- ^ Hoeveler, Diane. “The Cosmic Pawnshop We Call Life: Nathanael West, Bergson, Capitalism and Schizophrenia.” Studies in Short Fiction 33.3 (1996): 411-423.

Works by Nathanael West Novels Short stories "Business Deal" · "The Imposter" · "Western Union Boy" · "Mr. Potts of Pottstown" · "The Adventurer" · "Three Eskimos" · "Tibetan Night"Poetry Plays Screenplays

(in collaboration with others, unless noted otherwise)Republic Pictures Ticket to Paradise · Follow Your Heart · The President's Mystery · Gangs of New York · Jim Hanvey - Detective · Rhythm in the Clouds · Ladies in Distress · Bachelor Girl · Born to be Wild · It Could Happen to You · Orphans of the Street · Stormy WeatherColumbia Pictures RKO Radio Pictures Five Came Back · Men Against the Sky (solo screenwriting credit) · Let's Make Music (solo screenwriting credit) · Before the Fact (never filmed) · Stranger on the Third FloorUniversal Studios Categories:- 1933 novels

- American novels

- Novels by Nathanael West

- American novels adapted into films

- Novels set in New York City

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.