- Columbanus

-

Saint Columbanus

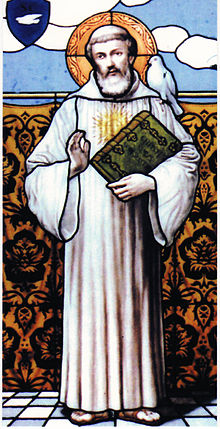

St. Columbanus. Window of the crypt of the Bobbio AbbeyBorn 540

Nobber, Kingdom of MeathDied 23 November 615

Bobbio, Kingdom of the LombardsFeast 24 November Patronage motorcyclists Saint Columbanus (540 – 23 November 615; Irish: Columbán, meaning "the white dove") was an Irish missionary notable for founding a number of monasteries on the European continent from around 590 in the Frankish and Lombard kingdoms, most notably Luxeuil (in present-day France) and Bobbio (Italy), and stands as an exemplar of Irish missionary activity in early medieval Europe.

He spread among the Franks a Celtic monastic rule and Celtic penitential practices for those repenting of sins, which emphasized private confession to a priest, followed by penances levied by the priest in reparation for the sin. He is also one of the earliest identifiable Hiberno-Latin writers.

Contents

Biography

Columbanus (the Latinised form of Columbán) was born in Nobber, County Meath, Ireland, in the year Saint Benedict died, and from childhood was well instructed. His name may be looked on as the diminutive of "Colm" (a dove), or as Colm (Colum) Bán meaning the 'white dove'.

He left home to study under Sinell, Abbot of Cluaninis in Lough Erne. The Irish words "Cluan Innish", which mean "meadow and island", have been contracted to "Cleenish", where the remains of the monastery can be seen at Bellanaleck, County Fermanagh. Under Sinell's instruction, Columbanus composed a commentary on the Psalms (for another identification, see Mo Sinu moccu Min). He then moved to the celebrated monastery of Bangor on the coast of Down, which at that time had for its abbot St. Comgall. He spent many years there until c.589 he received Comgall's permission to travel to the continent.[1]

Columbanus set sail with twelve companions; their names are believed to be St. Attala, Columbanus the Younger, Cummain, Domgal (Deicolus?), Eogain, Eunan, St. Gall, Gurgano, Libran, Lua, Sigisbert and Waldoleno (Strokes, "Apennines", p. 112). This little band passed over to Britain, landing probably on the Scottish coast. Some contend they may have landed in and crossed Cornwall enroute to Brittany. They remained only a short time in England and then crossed over to France. The landing site of Columbanus is marked by a shrine at Carnac in Brittany.

He and his followers soon made their way to the court of Gontram, King of Burgundy. Jonas calls it the court of Sigisbert, King of Austrasia and Burgundy, but this is manifestly a blunder, for Sigisbert had been slain in 575. The fame of Columbanus had preceded him. Gontram gave him a gracious reception, inviting him to remain in his kingdom. The saint complied, and selected for his abode the half-ruined Roman fortress at Annegray in the solitudes of the Vosges mountains.

Here the abbot and his monks led the simplest of lives, their food often consisting of nothing but forest herbs, berries, and the bark of young trees. The fame of Columbanus's sanctity drew crowds to his monastery. Many, both nobles and rustics, asked to be admitted into the community. Sick persons came to be cured through their prayers. But Columbanus loved solitude. Often he would withdraw to a cave seven miles distant, with a single companion who acted as messenger between himself and his brethren.

After a few years, the ever-increasing number of his disciples obliged him to build another monastery. Columbanus accordingly obtained from King Gontram the Gallo-Roman castle named "Luxovium" (Luxeuil), some eight miles distant from Annegray. It was in a wild district, thickly covered with pine forests and brushwood. A third monastery was erected at Fontaines. The superiors of these houses always remained subordinate to Columbanus. It is said that at this time he instituted a perpetual service of praise, known as laus perennis, by which choir succeeded choir, both day and night (Montalembert, Monks of the West II, 405). He wrote his Rule for these flourishing communities, which embodied the customs of Bangor and other Celtic monasteries.

For nearly 20 years Columbanus resided in France and, during that time, observed the unreformed paschal computation. But a dispute arose. The Frankish bishops were not well disposed towards this stranger abbot, because of his ever-increasing influence, and at last they showed their hostility. They objected to his Celtic Easter and his exclusion of men as well as women from the precincts of his monasteries.

The councils of Gaul held in the first half of the sixth century had given to bishops absolute authority over religious communities, even going so far as to order the abbots to appear periodically before their respective bishops to receive reproof or advice, as might be considered necessary. These enactments, being contrary to the custom of the Celtic monasteries, were readily rejected by Columbanus. In 602 the bishops assembled to judge him. He did not appear, lest, as he tells us, "he might contend in words", but instead addressed a letter to the prelates in which he speaks with a strange mixture of freedom, reverence, and charity. In it he admonishes them to hold synods more frequently, and advises that they pay attention to matters equally important with that of the date of Easter.

As to his paschal cycle he says: "I am not the author of this divergence. I came as a poor stranger into these parts for the cause of Christ, Our Saviour. One thing alone I ask of you, holy Fathers, permit me to live in silence in these forests, near the bones of 17 of my brethren now dead." When the Frankish bishops still insisted the abbot was wrong in obedience to St. Patrick's canon, he laid the question before the Pope St. Gregory I. He dispatched two letters to that pontiff, but they never reached him, "through Satan's intervention". The third letter is extant, but no trace of an answer appears in St. Gregory's correspondence, owing probably to the fact that the pope died in 604, about the time it reached Rome. In this letter he defended the Celtic custom with considerable freedom but the tone is affectionate. He prays "the holy Pope, his Father", to direct towards him "the strong support of his authority, to transmit the verdict of his favour". Moreover, he apologizes "for presuming to argue, as it were, with him who sits in the chair of Peter, Apostle and Bearer of the Keys".

He directed another epistle to Pope Boniface IV, in which he prays that, if it be not contrary to the Faith, he confirm the tradition of his elders, so that by the papal decision (judicium) he and his monks may be enabled to follow the rites of their ancestors. Before Pope Boniface's answer (which has been lost) was given, Columbanus was outside the jurisdiction of the Frankish bishops. As we hear no further accusation on the Easter question—not even in those brought against his successor at Luxeuil Abbey, Eustasius of Luxeuil in 624—it would appear that after Columbanus had moved to Italy, he gave up the Celtic Easter (cf. Acta SS. O.S.B., II, p. 7).

In addition to the Easter question, Columbanus had to wage war against vice in the royal household. The young Theodoric, to whose kingdom Luxeuil belonged, was living a life of debauchery. He was completely under the influence of his grandmother, Queen Brunehault (Brunehild). On the death of King Gontram, the succession passed to his nephew, Childebert II, son of Brunehault. At his death the latter left two sons, Theodebert II and Thierry II, both minors. Theodebert succeeded to Austrasia, Thierry to Burgundy, but Brunehault constituted herself their guardian, and held in her own power the governments of the two kingdoms.

As she advanced in years she sacrificed everything to the passion of sovereignty, she encouraged Thierry in the practice of concubinage in order that there might be no rival queen. Thierry, however, had a veneration for Columbanus, and often visited him. On these occasions the saint admonished and rebuked him, but in vain. Brunehault became enraged with Columbanus, stirred up the bishops and nobles to find fault with his Rules regarding monastic enclosure. Finally, Thierry and his party went to Luxeuil and ordered the abbot to conform to the usages of the country. Columbanus refused, whereupon he was taken prisoner to Besançon to await further orders.

Taking advantage of the absence of restraint, he speedily returned to his monastery. On hearing this, Thierry and Brunehault sent soldiers to drive him back to Ireland. None but Irish monks were to accompany him. Accordingly, he was hurried to Nevers, made to embark on the Loire, and thus proceed to Nantes. At Tours he visited the tomb of Saint Martin and sent a message to Thierry predicting that, within three years, he and his children would perish. At Nantes, before the embarkation, he addressed a letter to his monks. In it he desires all to obey Attala, whom he requests to abide with the community unless strife should arise on the Easter question. His letter concludes thus "They come to tell me the ship is ready. The end of my parchment compels me to finish my letter. Love is not orderly; it is this which has made it confused. Farewell, dear hearts of mine; pray for me that I may live in God." As soon as they set sail, such a storm arose that ship was driven ashore. The captain would have nothing more to do with the monks; they were thus free to go where they pleased. Columbanus made his way to the friendly King Clothaire at Soissons in Neustria where he was gladly welcomed. Clothaire in vain pressed him to remain in his territory.

Columbanus left Neustria in 611 for the court of King Theodebert of Austrasia. At Metz he received an honourable welcome, and then proceeding to Mainz, he embarked upon the Rhine in order to reach the Suevi and Alamanni, to whom he wished to preach the Gospel. Ascending the river and its tributaries, the Aar and the Limmat, he came to the Lake of Zürich. Tuggen was chosen as a centre from which to evangelize, but the work was not successful. In despair he resolved to pass on by way of Arbon to Bregenz on Lake Constance, where there were still some traces of Christianity. Here the saint found an oratory dedicated to St. Aurelia, into which the people had brought three brass images of their tutelary deities. He commanded Saint Gall, who knew the language, to preach to the inhabitants, and many were converted. The images were destroyed, and Columbanus blessed the little church, placing the relics of St. Aurelia beneath the altar. A monastery was erected, and the brethren forthwith observed their regular life.

Columbanus is reported to have performed a miracle in Bregenz: The townpeople had placed a large vessel in the town center, filled with beer. They told Columbanus it was intended as a sacrifice to their god Wodan (Illi aiunt se Deo suo Vodano nomine), whom they identified with Roman Mercury. Angrily, Columbanus breathed on the vessel, which broke asunder with a loud noise, spilling the beer. After about a year, in consequence of another rising against the community, Columbanus resolved to cross the Alps into Italy. An additional reason for his departure was the fact that the arms of Thierry had prevailed against Theodebert, and thus the country on the banks of the Upper Rhine had become the property of his enemy.

On his arrival at Milan in 612, Columbanus met with a kindly welcome from Lombard King Agilulf and Queen Theodelinda. He immediately began to confute the Arians and wrote a treatise against their teaching, which has been lost. At the request of the king, he wrote a letter to Pope Boniface on the debated subject of "The Three Chapters". These writings were considered to favour Nestorianism.

Pope St. Gregory, however, tolerated in Lombardy those persons who defended them, among whom was King Agilulf. Columbanus would probably have taken no active part in this matter had not the king pressed him so to do. But on this occasion his zeal certainly outran his knowledge. The letter opens with all apology that a "foolish Scot" should be charged to write for a Lombard king. He acquaints the pope with the imputations brought against him, and he is particularly severe with the memory of Pope Vigilius. He entreats the pontiff to prove his orthodoxy and assemble a council. He says that his freedom of speech accords with the usage of his country. "Doubtless", Montalembert remarks, "some of the expressions which he employs should be now regarded as disrespectful and justly rejected. But in those young and vigorous times, faith and austerity could be more indulgent" (II, 440).

On the other hand, the letter expresses the most affectionate and impassioned devotion to the Holy See. The whole, however, may be judged from this fragment: "We Irish, though dwelling at the far ends of the earth, are all disciples of St. Peter and St. Paul... we are bound [devincti] to the Chair of Peter, and although Rome is great and renowned, through that Chair alone is she looked on as great and illustrious among us ... On account of the two Apostles of Christ, you [the pope] are almost celestial, and Rome is the head of the whole world, and of the Churches". If zeal for orthodoxy caused him to overstep the limits of discretion, his real attitude towards Rome is sufficiently clear. He declares the pope to be: "his Lord and Father in Christ", "The Chosen Watchman", "The Prelate most dear to all the Faithful", "The most beautiful Head of all the Churches of the whole of Europe", "Pastor of Pastors", "The Highest", "The First", "The First Pastor, set higher than all mortals", "Raised near into all the Celestial Beings", "Prince of the Leaders", "His Father", "His immediate Patron", "The Steersman", "The Pilot of the Spiritual Ship" (Allnatt, "Cathedra Petri", 106).

But it was necessary that, in Italy, Columbanus should have a settled abode, so the king gave him a tract of land called Bobbio, between Milan and Genoa, near the River Trebbia, situated in a defile of the Apennines. On his way there he taught the Faith in the town of Mombrione, which is called San Colombano to this day. Padre della Torre considers that the saint made two journeys into Italy, which were confounded by Jonas. On the first occasion he went to Rome and received from Pope Gregory many sacred relics (Stokes, Apennines, 132). This may possibly explain the traditional spot in St. Peter's, where St. Gregory and St. Columba are supposed to have met (Moran, Irish SS. in Great Britain, 105). At Bobbio the saint repaired the half-ruined church of St. Peter, and erected his celebrated abbey, which for centuries was stronghold of orthodoxy in Northern Italy. Thither came Clothaire's messengers inviting the aged abbot to return, now that his enemies were dead. But he could not go.

He sent a request that the king would always protect his monks at Luxeuil. He prepared for death by retiring to his cave on the mountain-side overlooking the Trebbia, where, according to a tradition, he had dedicated an oratory to Our Lady (Montalembert, "Monks of the West", II, 444). He died at Bobbio (in part the model for the great monastery in Umberto Eco's novel The Name of the Rose) in 615.

Among his principal miracles are: (1) procuring of food for a sick monk and curing the wife of his benefactor; (2) escape from hurt when surrounded by wolves; (3) obedience of a bear which evacuated a cave at his biddings; (4) producing a spring of water near his cave; (5) repletion of the Luxeuil granary when empty; (6) multiplication of bread and beer for his community; (7) curing of the sick monks, who rose from their beds at his request to reap the harvest; (8) giving sight to a blind man at Orleans; (9) taming a bear, and yoking it to a plough.

Columbanus' monastic rule

The Monastic Rule of St. Columbanus is much shorter than that of St. Benedict, consisting of only ten chapters. The first six of these treat of obedience, silence, food, poverty, humility, and chastity. In these there is much in common with the Benedictine code, except that the fasting is more rigorous. Chapter VII deals with the Choir Offices. Chapter X regulates penances (often corporal) for offences, and it is here that the Rule of St. Columbanus differs so widely from that of St. Benedict. Stripes or fasts were enjoined for the smallest faults.

The habit of the monks consisted of a tunic of undyed wool, over which was worn the cuculla, or cowl, of the same material. A great deal of time was devoted to various kinds of manual labour, not unlike the life in monasteries of other rules. The Rule of St. Columbanus was approved of by the Council of Mâcon in 627, but it was destined before the close of the century to be superseded by that of St. Benedict. For several centuries in some of the greater monasteries the two rules were observed conjointly.

Other writings

A number of works by Columbanus survive, including a monastic rule (the Regula monachorum), a number of letters, and some poetry (see Columcille the Scribe). These provide some of the earliest evidence for Irish knowledge of Latin. In addition, Columbanus created the Communal Rule which is "very evident of his time"

Legacy and veneration

Like other men, Columbanus was not faultless. He was impetuous and even head-strong, for by nature he was eager, passionate, and dauntless. These qualities were both the source of his power and the cause of mistakes. But his virtues were very remarkable. He shared with other saints a great love for God's creatures. As he walked in the woods, the birds would alight upon his shoulder that he might caress them and the squirrels would run down from the trees and nestle in the folds of his cowl.

The fascination of his saintly personality drew numerous communities around him. That he possessed real affection for others is abundantly manifest in his letter to his brethren. Archbishop Healy eulogises him thus: "A man more holy, more chaste, more self-denying, a man with loftier aims and purer heart than Columbanus was never born in the Island of Saints" (Ireland's Ancient Schools, 378).

Regarding his attitude towards the Holy See, although with Celtic warmth and flow of words he could defend mere custom, there is nothing in his strongest expressions which implies that he for a moment doubted Rome's supreme authority. His influence in Europe was due to the conversions he effected and to the rule that he composed. It may be that the example and success of St. Columba in Caledonia stimulated him to similar exertions. The example, however, of Columbanus in the sixth century stands out as the prototype of missionary enterprise towards the countries of Europe, so eagerly followed up from England and Ireland by such men as Saints Killian, Virgilius, Donatus, Wilfrid, Willibrord, Swithbert, Boniface, and Ursicinus of Saint-Ursanne.

If Columbanus's abbey at Bobbio in Italy became a citadel of faith and learning, Luxeuil in France became the nursery of saints and apostles. From its walls went forth men who carried his rule, together with the Gospel, into France, Germany, Switzerland, and Italy. There are said to have been sixty-three such apostles (Stokes, Forests of France, 254). These disciples of Columbanus are accredited with founding over one hundred different monasteries (ib., 74). The canton and town still bearing the name of St. Gall testify how well one disciple succeeded.

Veneration

His body has been preserved in the abbey church at Bobbio, and many miracles are said to have been wrought there through his intercession. In 1482 the relics were placed in a new shrine and laid beneath the altar of the crypt. The sacristy at Bobbio possesses a portion of the skull of the saint, his knife, wooden cup, bell, and an ancient water vessel, formerly containing sacred relics and said to have been given to him by St. Gregory. According to certain authorities, twelve teeth of the saint were taken from the tomb in the fifteenth century and kept in the treasury, but these have now disappeared (Stokes, Apennines, p. 183).

St. Columbanus is named in the Roman Martyrology on 23 November, but his feast is kept by the Benedictines and throughout Ireland on 24 November. Columbanus is the patron saint of motorcyclists.

In art St. Columbanus is represented bearded bearing the monastic cowl, he holds in his hand a book with an Irish satchel, and stands in the midst of wolves. Sometimes he is depicted in the attitude of taming a bear, or with sun-beams over his head (Husenheth, "Emblems", p. 33).

Bibliography

- Patrick T.R. Gray, Michael W. Herren, "Columbanus and the Three Chapters Controversy: A New Approach," Journal of Theological Studies, NS, 45 (1994) 160-170.

- Michael Lapidge (ed), Columbanus: Studies in Latin Writings (Woodbridge, Boydell, 1997).

- Alexander O'Hara, "The Vita Columbani in Merovingian Gaul," Early Medieval Europe, 17,2 (2009), 126-153.

- Michael Richter, Bobbio in the Early Middle Ages: The Abiding Legacy of Columbanus (Dublin, Four Courts Press, 2008).

References

- ^ Wallace,Martin.A Little Book of Celtic Saints. Belfast. Appletree Press, 1995 ISBN0-86281-456-1, p.43

Sources and external links

- The main source for Columbanus's life is recorded by Jonas of Bobbio, an Italian monk who entered the monastery in Bobbio in 618, three years after the saint's death; Jonas wrote the life c. 643. This author lived during the abbacy of Attala, Columbanus's immediate successor, and his informants had been companions of the saint. Mabillon in the second volume of his "Acta Sanctorum O.S.B." gives the life in full, together with an appendix on the miracles of the saint, written by an anonymous member of the Bobbio community.

- Life of St. Columban, English translation

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed (1913). "St. Columbanus". Catholic Encyclopedia. Robert Appleton Company.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed (1913). "St. Columbanus". Catholic Encyclopedia. Robert Appleton Company.- St. Columban, Abbot and Confessor – St. Columban Parish, Loveland, Ohio

- Knights of St. Columbanus

- About the Knights of St. Columbanus

Categories:- Irish writers

- Irish literature

- Early medieval Latin writers

- 543 births

- 615 deaths

- Medieval Gaels

- Irish Christian missionaries

- Founders of Roman Catholic religious communities

- 7th-century Christian saints

- Burials at Bobbio Abbey

- 6th-century Christians

- Medieval Irish saints

- 6th-century Irish people

- 7th-century Irish people

- People from County Meath

- Irish expatriates in France

- Irish expatriates in Italy

- Medieval Irish saints on the Continent

- Medieval Irish writers

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.