- Halo effect

-

For the books of the same name, see Halo Effect (disambiguation).

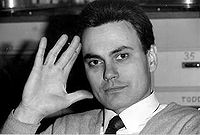

When we judge the looks of John Ausonius, it could matter if we think he is a) a blossoming movie star, b) an award-winning scientist, or c) a bankrobber and attempted serial killer.

When we judge the looks of John Ausonius, it could matter if we think he is a) a blossoming movie star, b) an award-winning scientist, or c) a bankrobber and attempted serial killer.

The halo effect is a cognitive bias whereby the perception of one trait (i.e. a characteristic of a person or object) is influenced by the perception of another trait (or several traits) of that person or object. An example would be judging a good-looking person as more intelligent.

Edward Thorndike was the first to support the halo effect with empirical research. In a psychology study published in 1920, Thorndike asked commanding officers to rate their soldiers; he found high cross-correlation between all positive and all negative traits. People seem not to think of other individuals in mixed terms; instead we seem to see each person as roughly good or roughly bad across all categories of measurement.

A study by Solomon Asch suggests that attractiveness is a central trait, so we presume all the other traits of an attractive person are just as attractive and sought after.

The halo effect is involved in Harold Kelley's implicit personality theory, where the first traits we recognize in other people influence our interpretation and perception of later ones because of our expectations. Attractive people are often judged as having a more desirable personality and more skills than someone of average appearance.

Karen Dion's 1972 study showed the same result. She set an experiment in which she showed photographs to people, and asked them to make a judgment of the people in the photos. In the result, attractive people are assumed to have a good personality as well as being sexually warm and responsive.

The term has also been used in regard to human rights organizations who use their status but move away from their stated goals. For example, Gerald M. Steinberg, the founder and president of NGO Monitor, claims that non-governmental organizations (NGOs) take advantage of a "halo effect" and are "given the status of impartial moral watchdogs" by governments and the media.[1]

Contents

Reverse halo effect

A corollary to the halo effect is the reverse halo effect where individuals, brands or other things judged to have a single undesirable trait are subsequently judged to have many poor traits, allowing a single weak point or negative trait to influence others' perception of the person, brand or other thing in general.[2][3]

As a business model

In brand marketing, a halo effect is one where the perceived positive features of a particular item extend to a broader brand. It has been used to describe how the iPod has had positive effects on perceptions of Apple's other products.[4] The effect is also exploited in the automotive industry, where a manufacturer may produce an exceptional halo vehicle in order to promote sales of an entire marque. Modern cars often described as halo vehicles include the Dodge Viper, Ford GT, and Acura NSX.[citation needed]

Unconscious judgments

In 1977, social psychologist Richard Nisbett demonstrated that even if we were told that our judgments have been affected by the halo effect, we may have no awareness of when the halo effect influences us.[5][6]

See also

- Affect heuristic

- Association fallacy

- Attribute substitution

- Confirmation bias

- List of cognitive biases

Notes

- ^ Nathan Jeffay, Academic hits out at politicised charities Interview with Gerald Steinberg, The Jewish Chronicle, June 24, 2010

- ^ Weisman, Jonathan (August 9, 2005). "Snow Concedes Economic Surge Is Not Benefiting People Equally". washingtonpost.com. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2005/08/08/AR2005080801445_pf.html. Retrieved 2008-05-12.

- ^ Deutsch, Claudia H. (August 16, 2006). "With Its Stock Still Lackluster, G.E. Confronts the Curse of the Conglomerate". nytimes.com. http://www.nytimes.com/2006/08/16/business/16place.html?n=Top%2FReference%2FTimes%20Topics%2FSubjects%2FC%2FCorporations. Retrieved 2008-05-12.

- ^ Wilcox, Joe (August 22, 2008). "The iPhone Halo Effect". Apple Watch - eweek.com. http://blogs.eweek.com/applewatch/content/mac_os_x/the_iphone_halo_effect.html. Retrieved 2008-09-10.

- ^ Nisbett, R. E. and Wilson, T. D. (1977). Telling more than we can know: Verbal reports on mental processes. Psychological review, 84(3), 231-259.

- ^ Nisbett, R. E. and Wilson, T. D. (1977) The halo effect: Evidence for unconscious alteration of judgments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 35(4), 250-256.

Further reading

- Nisbett, Richard E.; Timothy D. Wilson (1977). "The halo effect: Evidence for unconscious alteration of judgments". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology (American Psychological Association) 35 (4): 250–256. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.35.4.250. ISSN 1939-1315.

- Stuart Sutherland (2007). Irrationality Second Edition (First Edition 1994) Pinter & Martin. ISBN 978-1-905177-07-3

- Jeremy Dean (2007). "The Halo Effect: When Your Own Mind is a Mystery" PsyBlog

- Rosenzweig, P. (2007) The Halo Effect: and the Eight Other Business Delusions That Deceive Managers ISBN 978-0-7432-9125-5

References

- Asch, S.E. (1946). Forming impressions of personality. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 41, 258-290

- Thorndike, E.L. (1920). A constant error on psychological rating. Journal of Applied Psychology, IV, 25-29

- Kelly, G.A. (1955). The psychology of personal constructs (Vols. 1 and 2). New York: Norton.

- What is beautiful is good. Dion, Karen; Berscheid, Ellen; Walster, Elaine. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. Vol 24(3), Dec 1972, 285-290 [doi.apa.org/getuid.cfm?uid=1973-09160-001]

Categories:- Cognitive biases

- Educational psychology

- Social psychology

- Logical fallacies

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.