- Morphosyntactic alignment

-

Linguistic typology Morphological Isolating Synthetic Polysynthetic Fusional Agglutinative Morphosyntactic Alignment Accusative Ergative Split ergative Philippine Active–stative Tripartite Marked nominative Inverse marking Syntactic pivot Theta role Word Order VO languages Subject–verb–object Verb–subject–object Verb–object–subject OV languages Subject–object–verb Object–subject–verb Object–verb–subject Time–manner–place Place–manner–time In linguistics, morphosyntactic alignment is the system used to distinguish between the arguments of transitive verbs and those of intransitive verbs. The distinction can be made morphologically (through grammatical case or verbal agreement), syntactically (through word order), or both.

Contents

Semantics and grammatical relations

Transitive verbs have two core arguments, which in a language like English are subject (A) and object (O). (The symbol P for patient is sometimes used for the latter role.) Intransitive verbs have a single core argument, which in English is the subject (S). Note that while the grammatical role labels S, A, and O/P are originally short for "subject", "agent", and "object/patient", the concepts of S, A, and O/P are distinct both from the terms "subject" and "object", which S, A and O supersede, and from "Agent" and "patient" (which indicate thematic relations, not grammatical relations: an A need not be an agent, an O need not be a patient).

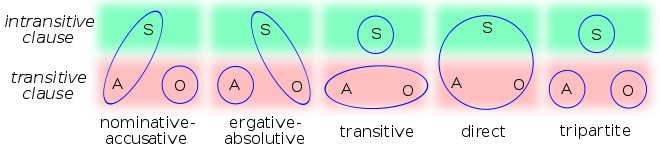

Of the three types of core argument (S, A and O), different constructions within a language often treat two the same way and the third distinctly.

- Nominative–accusative alignment treats the S argument of an intransitive verb like the A argument of transitive verbs, with the O argument distinct (S = A; O separate) (see nominative–accusative language). In a language with morphological case marking, an S and an A may both be unmarked or marked with the nominative case, while the O is marked with an accusative case as occurs with nominative -us and accusative -um in Latin: Julius venit "Julius came"; Julius Brutum vidit "Julius saw Brutus". Languages with nominative–accusative alignment can detransitivize transitive verbs by demoting the A argument, and promoting the O to be an S (thus taking nominative case marking); this is called the passive voice.

An unusual subtype is called marked nominative or nominative–absolutive; in such languages, the subject of a verb is marked for nominative case, but the object is unmarked, as are citation forms and objects of prepositions. Such alignments are only clearly documented in northeastern Africa and the southwestern United States.

- Ergative–absolutive alignment treats an intransitive argument like a transitive O argument (S=O; A separate) (see ergative–absolutive language). An A may be marked with an ergative case (sometimes formally the same as the genitive or instrumental case or some other oblique case), while the S argument of an intransitive verb and the O argument of a transitive verb are left unmarked or sometimes marked with an absolutive case. Ergative–absolutive languages can detransitivize transitive verbs by demoting the O and promoting the A to an S, thus taking the absolutive case; this is called the antipassive voice.

- Fluid (or semantic) alignment (see active–stative languages) treats the arguments of some intransitive verbs in the same way as the A argument of transitives, and the single arguments of other intransitive verbs the same as transitive O arguments (Sa=A; So=O). The reason for assignment to one class or another usually has a straightforward semantic basis. For example, in Georgian, Mariamma imğera "Mary sang", shares the same narrative case ending as the transitive clause Mariamma c'erili dac'era "Mary wrote the letter", while in Mariami iq'o Tbilisši revolutsiamde "Mary was in Tbilisi up to the revolution", Mary shares the same case ending (-i) as the object in the transitive clause. Thus the class of intransitive is not uniform in its behavior. The particular criteria for assigning verbs to one class or the other vary from language to language, and may either be fixed lexically for each verb, or chosen by the speaker according to the degree of volition, control, or suffering of the verbal action by the participant, or the degree of sympathy the speaker has.

- The Austronesian languages of the Philippines, Borneo, Taiwan, and Madagascar are well known for having both alignments, called voices. These are the Austronesian-alignment or Philippine-type languages. The alignments are often misleadingly called "active" and "passive" voice, but both have two core arguments, so increasingly the terms such as "actor focus" or "agent trigger" are used for the accusative type, and "undergoer focus" or "patient trigger" for the ergative type (though these are not focus systems either). Patient-trigger alignment is the default in most of these languages. For either alignment two core cases are used, but the same morphology is used for the nominative of the agent-trigger alignment and the absolutive of the patient-trigger alignment, so there is a total of just three core cases: nominative–absolutive (usually called nominative, or sometimes direct), ergative, and accusative. Many Austronesianists argue that these languages have four alignments, with voices that mark a locative or benefactive with the direct case, but others maintain that these are not basic to the [Mitä] system.

A very few languages make no distinction whatsoever between agent, patient, and intransitive arguments, leaving the hearer to rely entirely on context and common sense to figure them out. Some others, called tripartite languages, use a separate case or syntax for each argument, which are conventionally called the accusative case, the intransitive case, and the ergative case. Certain Iranian languages, such as Rushani, distinguish only transitivity, using a transitive case, for both A and O, and an intransitive case.

The common types of alignment, and some uncommon, can be shown graphically like this:

Furthermore, a single language may use nominative–accusative and ergative–absolutive systems in different grammatical contexts, sometimes linked to animacy (Australian Aboriginal languages) or aspect (Mayan languages). This is called split ergativity.

Another popular idea (introduced by Anderson 1976[1]) is that some constructions universally favor accusative alignment while others are more flexible. In general, behavioral constructions (control, raising, relativization) are claimed to favor nominative–accusative alignment, while coding constructions (especially case constructions) do not show any alignment preferences. This idea underlies early notions of ‘deep’ vs. ‘surface’ (or ‘syntactic’ vs. ‘morphological’) ergativity (e.g. Comrie 1978;[2] Dixon 1994[3]): many languages have surface ergativity only, i.e. ergative alignments only in their coding constructions (like case or agreement) but not in their behavioral constructions, or at least not in all of them. Languages with deep ergativity, i.e. with ergative alignment in behavioral constructions, appear to be less common.Ergative vs. accusative

Ergative languages contrast with nominative–accusative languages (such as English), which treat the objects of transitive verbs distinctly from other core arguments.

These different arguments can be symbolized as follows:

- O = most patient-like argument of a transitive clause (also symbolized as P)

- S = sole argument of an intransitive clause

- A = most agent-like argument of a transitive clause

The S/A/O terminology avoids the use of terms like "subject" and "object", which are not stable concepts from language to language. Moreover, it avoids the terms "agent" and "patient", which are semantic roles that do not correspond consistently to particular arguments. For instance, the A might be an experiencer or a source, semantically, not just an agent.

The relationship between ergative and accusative systems can be schematically represented as the following:

Ergative–absolutive Nominative–accusative O same different S same same A different same The following Basque examples demonstrate ergative–absolutive case marking system:

-

Ergative Language Sentence: Gizona etorri da. Gizonak mutila ikusi du. Words: gizona-∅ etorri da gizona-k mutila-∅ ikusi du Gloss: the.man-ABS has arrived the.man-ERG boy-ABS saw Function: S VERBintrans A O VERBtrans Translation: 'The man has arrived.' 'The man saw the boy.'

In Basque, gizona is "the man" and mutila is "the boy". In a sentence like mutila gizonak ikusi du, you know who's seeing whom because -k is always added to the one doing the seeing. So this means 'the man saw the boy'. To say 'the boy saw the man', just add the "-k" to the boy: mutilak gizona ikusi du.

With a verb like etorri "come" there's no need to tell "who's coming whom", so no -k is ever added. "The boy came" is 'mutila etorri da'.

To contrast with a nominative–accusative language, Japanese marks nouns with a different case marking:

-

Accusative Language Sentence: Kodomo ga tsuita. Otoko ga kodomo o mita. Words: kodomo ga tsuita otoko ga kodomo o mita Gloss: child NOM arrived man NOM child ACC saw Function: S VERBintrans A O VERBtrans Translation: 'The child arrived.' 'The man saw the child.'

In this language, in the sentence "man saw child", the one doing the seeing (man) may be marked with ga, which works like Basque "-k" (and the one who is seen may be marked with o). However, in the sentences like the child arrived, where there's no need of telling "who arrived whom", there may be a ga. This is unlike Basque, where "-k" is completely forbidden in such sentences.

See also

References

- ^ Anderson, Stephen. (1976). On the notion of subject in ergative languages. In C. Li. (Ed.), Subject and topic (pp. 1–24). New York: Academic Press.

- ^ Comrie, Bernard. (1978). Ergativity. In W. P. Lehmann (Ed.), Syntactic typology: Studies in the phenomenology of language (pp. 329–394). Austin: University of Texas Press.

- ^ Dixon, R. M. W. (1994). Ergativity. Cambridge University Press.

Further reading

- Anderson, Stephen. (1976). On the notion of subject in ergative languages. In C. Li. (Ed.), Subject and topic (pp. 1–24). New York: Academic Press.

- Anderson, Stephen R. (1985). Inflectional morphology. In T. Shopen (Ed.), Language typology and syntactic description: Grammatical categories and the lexicon (Vol. 3, pp. 150–201). Cambridge: University of Cambridge Press.

- Comrie, Bernard. (1978). Ergativity. In W. P. Lehmann (Ed.), Syntactic typology: Studies in the phenomenology of language (pp. 329–394). Austin: University of Texas Press.

- Dixon, R. M. W. (1979). Ergativity. Language, 55 (1), 59–138. (Revised as Dixon 1994).

- Dixon, R. M. W. (Ed.) (1987). Studies in ergativity. Amsterdam: North-Holland.

- Dixon, R. M. W. (1994). Ergativity. Cambridge University Press.

- Foley, William; & Van Valin, Robert. (1984). Functional syntax and universal grammar. Cambridge University Press.

- Kroeger, Paul. (1993). Phrase structure and grammatical relations in Tagalog. Stanford: CSLI.

- Mallinson, Graham; & Blake, Barry J. (1981). Agent and patient marking. Language typology: Cross-linguistic studies in syntax (Chap. 2, pp. 39–120). North-Holland linguistic series. Amsterdam: North-Holland Publishing Company.

- Patri, Sylvain (2007), L'alignement syntaxique dans les langues indo-européennes d'Anatolie, (StBoT 49), Otto Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden, ISBN 978-3-447-05612-0

- Plank, Frans. (Ed.). (1979). Ergativity: Towards a theory of grammatical relations. London: Academic Press.

- Schachter, Paul. (1976). The subject in Philippine languages: Actor, topic, actor–topic, or none of the above. In C. Li. (Ed.), Subject and topic (pp. 491–518). New York: Academic Press.

- Schachter, Paul. (1977). Reference-related and role-related properties of subjects. In P. Cole & J. Sadock (Eds.), Syntax and semantics: Grammatical relations (Vol. 8, pp. 279–306). New York: Academic Press.

External links

- WALS Alignment of Case Marking of Full Noun Phrases

- Case Marking and Ergativity: an article on Jiwarli with a clear explanation of nominative–accusative, ergative–absolutive and tripartite systems

Categories:

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.