- Discovery (law)

-

This article is about pre-trial phase of a lawsuit. For about the discovery of land under public international law, see Discovery Doctrine.

Civil procedure in the United States - Federal Rules of Civil Procedure

- Doctrines of civil procedure

- Jurisdiction

- Subject-matter jurisdiction

- Diversity jurisdiction

- Personal jurisdiction

- Removal jurisdiction

- Venue

- Pleadings

- Pre-trial procedure

- Discovery

- Initial Conference

- Interrogatories

- Depositions

- Request for Admissions

- Request for production

- Resolution without trial

- Trial

- Parties

- Pro Se

- Jury

- Burden of proof

- Judgment

- Judgment as a matter of law (JMOL)

- Renewed JMOL (JNOV)

- Motion to set aside judgment

- New trial

- Remedy

- Injunction

- Damages

- Attorney's fees

- American rule

- English rule

- Declaratory judgment

- Appeal

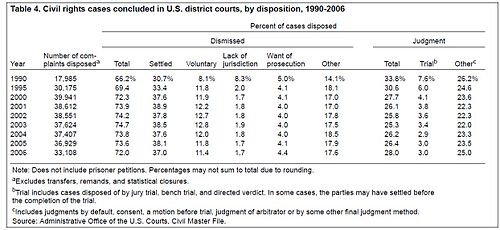

Civil rights cases concluded in U.S. district courts, by disposition, 1990-2006.[1]

Civil rights cases concluded in U.S. district courts, by disposition, 1990-2006.[1]

In U.S.law, discovery is the pre-trial phase in a lawsuit in which each party, through the law of civil procedure, can obtain evidence from the opposing party by means of discovery devices including requests for answers to interrogatories, requests for production of documents, requests for admissions and depositions. Discovery can be obtained from non-parties using subpoenas. When discovery requests are objected to, the requesting party may seek the assistance of the court by filing a motion to compel discovery.

Contents

Civil discovery in the United States

Main article: Civil discovery under United States federal lawSee also: Federal Rules of Civil ProcedureUnder the law of the United States, civil discovery is wide-ranging and can involve any material which is "reasonably calculated to lead to admissible evidence." This is a much broader standard than relevance, because it contemplates the exploration of evidence which might be relevant, rather than evidence which is actually relevant. (Issues of the scope of relevance are taken care of before trial in motions in limine and during trial with objections.) Certain types of information are generally protected from discovery; these include information which is privileged and the work product of the opposing party. Other types of information may be protected, depending on the type of case and the status of ther party. For instance, juvenile criminal records are generally not discoverable, peer review findings by hospitals in medical negligence cases are generally not discoverable and, depending on the case, other types of evidence may be non-discoverable for reasons of privacy, difficulty and/or expense in complying and for other reasons. (Criminal discovery rules may differ from those discussed here.) Electronic discovery or "e-discovery" refers to discovery of information stored in electronic format (often referred to as Electronically Stored Information, or ESI).

In practice, most civil cases in the United States are settled after discovery.[2] After discovery, both sides often are in agreement about the relative strength and weaknesses of each side's case and this often results in either a settlement or summary judgment, which eliminates the expense and risks of a trial.

At the federal level

Main article: Civil discovery under United States federal lawDiscovery in the United States is unique compared to other common law countries. In the United States, discovery is mostly performed by the litigating parties themselves, with relatively minimal judicial oversight. The Federal Rules of Civil Procedure guide discovery in the U.S. federal court system. Most state courts follow a similar version based upon the FRCP, Chapter V "Depositions & Discovery" [1].

According to the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, the plaintiff must initiate a conference between the parties after the complaint was served to the defendants, to plan for the discovery process.[3] The parties should attempt to agree on the proposed discovery schedule, and submit a proposed Discovery Plan to the court within 14 days after the conference.[3] After that, the main discovery process begins which includes: initial disclosures, depositions, interrogatories, request for admissions(RFA) and request for production of documents(RFP). In most of United States district (federal) courts the formal requests for interrogatories, request for admissions and request for production are exchanged between the parties and not filed with the court. Parties, however, can file motion to compel discovery if responses are not received within the FRCP time limit. Parties can file a motion for a protective order if the discovery requests become unduly burdensome or for purpose of harassment.

At the state level

Many states have adopted discovery procedures based on the federal system; some closely adhere to the federal model, others not so closely. Some states take an entirely different approach to discovery.

California

In California state courts, discovery is governed by the Civil Discovery Act of 1986 (Title 4 (Sections 2016-2036) of the Code of Civil Procedure), as subsequently amended.[4] A significant number of appellate court decisions have interpreted and construed the provisions of the Act.

California discovery requests are not continuing: the responding party only needs to respond with the facts as known on the date of the response, and is under no obligation to update its responses as new facts become known.[5] This causes many parties to reserve one or two interrogatories until the closing days of discovery, when they ask if any of the previous responses to discovery have changed, and then ask what the changes are. California depositions are not limited to one day, and objections must be made in detail or they are permanently waived. A party may only propound thirty-five written interrogatories on any other single party, and no "subparts, or a compound, conjunctive, or disjunctive question" may be included in an interrogatory; however, "form interrogatories" which have been approved by the state Judicial Council[6] do not count toward this limit. In addition, no "preface or instruction" may be included in the interrogatories unless it has been approved by the Judicial Council; in practice, this means that the only instructions permissible with interrogatories are the ones provided with the form interrogatories.

District of Columbia

The District of Columbia follows the federal rules, with a few exceptions. Some deadlines are different, and litigants may only resort to the D.C. Superior Court. Thirty-five interrogatories, including parts and sub-parts, may be propounded by one party on any other party. There is no requirement for a "privilege log": federal Rule 26(b)(5) was not adopted by the D.C. Superior Court. Where above is stated "litigants may only resort to the D.C. Superior Court" upon correction is found according to the District of Columbia Superior Court Rules of Civil Procedure Section 73(b)Judicial Review and Appeal which states: "Judicial review of a final order or judgement entered upon direction of a hearing commissioner is available on motion of a party to the Superior Court judge designated by the Chief Judge to conduct such reviews...After that review has been completed, appeal may be taken to the District of Columbia Court of Appeals." This rule basically implies that in a civil action, if a hearing commissioner is authorized by all parties to conduct the proceedings instead of a judge, upon a request for a review or appeal, the motion must first be reviewed by a Superior Court judge to the same standard as a motion for appeal on a Superior Court Judge to the Court of Appeals, but the right to appeal to the higher courts still remains.

Criticism of U.S. discovery

The use of discovery has been criticized as favoring the wealthier side, in that it enables parties to drain each other's financial resources in a war of attrition. For example, one can make information requests, which are expensive and time-consuming for the other side to fulfill; produce hundreds of thousands of documents of questionable relevance to the case; file requests for protective orders to prevent the deposition of key witnesses; and so on. In a critique of the U.S. legal profession, attorney and writer Cameron Stracher described a variety of unpleasant tactics common in the United States, and concluded:

“ With the noble sentiment of "levelling the playing field" so that no party has an undue information advantage, the writers of the discovery rules created a multilevel playing field where the information-rich can kick the information-poor in the head and escape unscathed. "Discovery" is anything but ... Hundreds of thousands of dollars to maintain the status quo, to preserve the information-rich at the expense of the information-poor. Thousands of lawyer hours to keep the discovery process as unrevealing as possible. The best minds of a generation thinking of new ways to manipulate, distort, and conceal.[7] ” Tort reform supporters argue that such tactics are often used by plaintiffs' lawyers to impose costs on defendants to force settlements in unmeritorious cases to avoid the cost of discovery. Victim's rights advocates, on the other hand, believe that the opposite is true: defendants typically have greater resources than plaintiffs and, accordingly, they impose costs on parties deserving compensation by dragging out the litigation process as opposed to offering a fair settlement.

Discovery in the United Kingdom

The same process in England and Wales is known as "disclosure," and is always[citation needed] used in complex civil litigation. As in the USA, certain documents are privileged, such as letters between solicitors and experts. Full details are given in Legal professional privilege (England & Wales).

See also

- Electronic Discovery

- Second request

- subpoena ad testificandum

- subpoena duces tecum

- Early case assessment

References

- ^ "Civil rights cases concluded in U.S. district courts, by disposition, 1990-2006". http://bjs.ojp.usdoj.gov/content/pub/pdf/crcusdc06.pdf.

- ^ [http://bjs.ojp.usdoj.gov/content/pub/pdf/crcusdc06.pdf "Civil Rights Complaints in U.S. District Courts"]. http://bjs.ojp.usdoj.gov/content/pub/pdf/crcusdc06.pdf.

- ^ a b "FRCP Rule 26". http://www.law.cornell.edu/rules/frcp/Rule26.htm.

- ^ See http://www.leginfo.ca.gov/cgi-bin/calawquery?codesection=ccp&codebody=&hits=20.

- ^ Singer v. Sup. Ct., 54 Cal.2d 318, 325 (1960).

- ^ E.g., http://www.courtinfo.ca.gov/forms/documents/disc001.pdf

- ^ Cameron Stracher, Double Billing: A Young Lawyer's Tale of Greed, Sex, Lies, and the Pursuit of a Swivel Chair (New York: William Morrow, 1998), 125–126.

External links

Categories:

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.