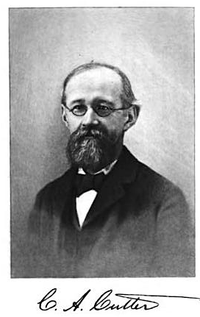

- Charles Ammi Cutter

-

Charles Ammi Cutter (14 March 1837 – 6 September 1903) is an important figure in the history of American library science.

Born in Boston, Massachusetts, Cutter was appointed assistant librarian of Harvard Divinity School while still a student there. After graduation, Cutter worked as a librarian at Harvard College, where he developed a new form of index catalog, using cards instead of published volumes, containing both an author index and a "classed catalog" or a rudimentary form of subject index.

Cutter's most significant contribution to the field of library science was the development of the Cutter Expansive Classification system. This system influenced the development of the Library of Congress. As part of his work on this system, he developed a system of alphabetic tables used to abbreviate authors' names and generate unique call numbers. This system of numbers ("Cutter numbers") is still used today in libraries.

Cutter was one of the 100 or so founding members, in 1876, of the American Library Association. Cutter is a member of the Library Hall of Fame.

While a student at the Harvard Divinity School, Cutter served as the student-librarian from 1857 to 1859. During his tenure, the then 1840 catalog had a lack of order after the recent acquisitions 4,000 volumes from the collection of Professor Gottfried Christian Friedrich Lücke of University of Göttingen, which added much depth to the Divinity School Library's collection. Along with classmate Charles Noyes, Cutter re-arranged the library collection on the shelves into broad subject categories during the 1857-58 school year. During the winter break of 1858-59, they arranged the collection into a single listing alphabetically by author. This project was finished by the time Cutter graduated in 1859.

After graduation, Cutter became an assistant to Dr. Ezra Abbot, the assistant librarian of the Harvard College Library.

In 1868 Cutter accepted a position at the Boston Athenæum library. One of its main goals was to publish a complete dictionary catalog for their collection. The previous librarian and assistants had been working on this when he left. Unfortunately, much of the work was sub par and, according to Cutter, needed to be redone . This did not sit well with the trustees who wanted to get a catalog published as soon as possible. However, the catalog was published. Cutter was the librarian at the Boston Athenaeum for twenty-five years. In 1876, Cutter was hired by the Bureau of Education to help write a report about the state of libraries for the Centennial. Part two of this report was his Rules for a Dictionary Catalog. He was also the editor of Library Journal from 1891-1893. Of the many articles he wrote during this time, one of the most famous was an article called “The Buffalo Public Library in 1983”. In it, he wrote what he thought a library would be like one hundred years in the future. He spent a lot of time discussing practicalities, such as how the library arranged adequate lighting and controlled moisture in the air to preserve the books. He also discussed a primitive version of interlibrary loan. After he had been at the Athenaeum for a while, a new group of trustees started to emerge. They were not as favorable to Cutter and his reforms, so the relationship soured.

In 1893, Cutter submitted a letter to the trustees that he would not seek to renew his contract at the end of the year. Fortunately for him, there was an opportunity in Northampton, Massachusetts. Judge Charles E. Forbes left a considerable amount of money to the town to start a library. This was Cutter’s chance to institute his ideas from the ground up. He developed a cataloging system called the expansive classification system. Unfortunately, he died in 1903 before he could finish. It was to have seven levels of classification, each with increasing specificity. Thus small libraries who did not like having to deal with unnecessarily long classification numbers could use lower levels and still be specific enough for their purpose. Larger libraries could use the more specific tables since they needed to be more specific to keep subjects separate. At Forbes, Cutter set up the art and music department and encouraged children of nearby schools to exhibit their art. He also established branch libraries and instituted a traveling library system much like the bookmobile. Today, Charles Ammi Cutter might be surprised to see his own portrait hanging over the reference librarians' desk in the Forbes Library in Northampton. His roll top desk is also in the office currently occupied by the recently elected director of the library.[1]

Charles Cutter died on September 6th, 1903 in Walpole, New Hampshire.

Contents

Future Predictions

"The desks had.. a little keyboard at each, connected by a wire. The reader had only to find the mark of his book in the catalog, touch a few lettered or numbered keys, and [the book] appeared after an astonishing short interval."

Charles Cutter "The Buffalo Public Library in 1983" (Library journal 1883)

See also

- Subject (documents)

Notes

- ^ Cutter Classification Forbes Library

External links

- Charles Cutter biography originally published in the Daily Hampshire Gazette, Northampton, MA

- Rules for a dictionary catalog, by Charles A. Cutter, fourth edition, hosted by the UNT Libraries Digital Collections

- The Buffalo Public Library in 1983, paper written in 1883, available on Wikisource.

- Andover-Harvard Theological Library Mission & history

- Charles Ammi Cutter: Nineteenth-Century Systematizer of Libraries. Dissertation by Dr. Francis Miksa, 1974. Chapter 2: Early Life and Harvard Years

Categories:- 1837 births

- 1903 deaths

- People from Boston, Massachusetts

- 19th-century American people

- Harvard Divinity School alumni

- American librarians

- American Library Association

- Harvard librarians

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.