- Literary nonsense

-

Literary nonsense (or nonsense literature) is a broad categorization of literature that uses sensical and nonsensical elements to defy language conventions or logical reasoning. Even though the most well-known form of literary nonsense is nonsense verse, the genre is present in many forms of literature.

The effect of nonsense is often caused by an excess of meaning, rather than a lack of it. Nonsense is often humorous in nature, although its humor is derived from its nonsensical nature, as opposed to most humor which is funny because it does make sense.[1]

Contents

History

The roots of literary nonsense are divided into two branches. The first and older branch is traced back to the folk tradition, folktales, dramas, rhymes, songs, and games, such as the nursery rhyme "Hey Diddle Diddle".[2] Schoolyard rhymes and the literary figure Mother Goose are somewhat contemporary incarnations of this style of writing. Its role in the folk tradition varies from mnemonic device to parody and satire.

The other branch of literary nonsense has its origins in the intellectual absurdities of court poets, scholars, and intellectuals of various kinds. These writers often created sophisticated nonsense forms of Latin parodies, religious travesties and political satire.[3]

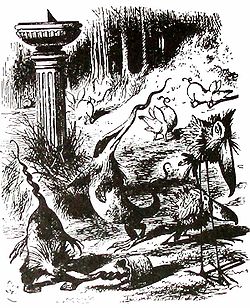

Today's literary nonsense comes from a combination of both branches.[4] Though not the first to write this hybrid kind of nonsense, Edward Lear developed and popularized it in his many limericks (starting with A Book of Nonsense, 1846) and other famous texts such as "The Owl and the Pussycat", "The Dong with a Luminous Nose," "The Jumblies" and "The Story of the Four Little Children Who Went Around the World." Lewis Carroll continued this trend, making literary nonsense a worldwide phenomenon with Alice's Adventures in Wonderland (1865) and Through the Looking-Glass (1871). Carroll's "Jabberwocky" which appears in Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There is often considered quintessential nonsense literature.[5]

Theory

In literary nonsense, formal diction and tone may be balanced with elements of absurdity. It is most easily recognizable by the various techniques it uses to create nonsensical effects, such as faulty cause and effect, portmanteau, neologism, reversals and inversions, imprecision, simultaneity, picture/text incongruity, arbitrariness, infinite repetition, negativity or mirroring, and misappropriation.[6] Nonsense tautology, reduplication, and absurd precision have also been used effectively in the nonsense genre.[7] For a text to be within the bounds of literary nonsense, it must have an abundance of nonsense techniques woven into the fabric of the piece. If the text employs only occasional nonsense techniques, then it may not be classified as literary nonsense, though there may be a nonsensical effect to certain portions of the work.[8]

Nonsense literature is effective because of the human desire to find meaning everywhere, in everything, and where perhaps none exists.[9]

What nonsense is not

Gibberish can be a form of nonsense, but true nonsense literature has semantic, syntactic, phonetic or contextual meaning.[10] Literature that employs the use of neologisms or made-up words is distinguished from gibberish if the context assigns meaning to those words or if word play is used to associate the gibberish with familiar words, such as "Jabberwocky" or "Hey Diddle Diddle".[11]

Nonsense is distinct from fantasy, though there are sometimes resemblances between them. While nonsense may employ the strange creatures, other worldly situations, magic, and talking animals of fantasy, these supernatural phenomena are not nonsensical if they have a discernible logic supporting their existence. The distinction lies in the coherent and unified nature of fantasy.[12] Everything follows logic within the rules of the fantasy world; the nonsense world, on the other hand, has no system of logic, although it may imply the existence of an inscrutable one, just beyond our grasp.[13] The nature of magic within an imaginary world is an example of this distinction. Fantasy worlds employ the presence of magic to logically explain the impossible. In nonsense literature, magic is rare but when it does occur, its nonsensical nature only adds to the mystery rather than logically explaining anything. An example of nonsensical magic occurs in Carl Sandburg's Rootabaga Stories, when Jason Squiff, in possession of a magical "gold buckskin whincher", has his hat, mittens, and shoes turn into popcorn because, according to the "rules" of the magic, "You have a letter Q in your name and because you have the pleasure and happiness of having a Q in your name you must have a popcorn hat, popcorn mittens and popcorn shoes".[14]

Riddles only appear to be nonsense until the answer is found. The most famous nonsense riddle is only so because it originally had no answer.[15] In Carroll's Alice in Wonderland, the Mad Hatter asks Alice "Why is a raven like a writing-desk?" When Alice gives up, the Hatter replies that he does not know either, creating a nonsensical riddle.[16] Some seemingly nonsense texts are actually riddles, such as the popular 1940's song "Mairzy Doats", which at first appears to have little discernible meaning but has a discoverable message.[17]

Audience

While most contemporary nonsense has been written for children, the form has an extensive history in adult configurations before the nineteenth century. Figures such as John Hoskyns, Henry Peacham, John Sanford, and John Taylor lived in the early seventeenth century and were noted nonsense authors in their time.[18] Nonsense was also an important element in the works of Flann O'Brien and Eugene Ionesco. Literary nonsense, as opposed to the folk forms of nonsense that have always existed in written history, was only first written for children in the early nineteenth century. It was popularized by Edward Lear and then later by Lewis Carroll. Today literary nonsense enjoys a shared audience of adults and children.

Nonsense writers

The most celebrated nonsense writers in English literature are Edward Lear (1812–1888) and Lewis Carroll (Charles Lutwidge Dodgson) (1832–1898).

Other nonsense writers in English literature:

- Douglas Adams

- Ivor Cutler

- Nicholas Daly

- Dave Eggers and his brother Christopher, writing as Dr. and Mr. Doris Haggis-on-Whey

- Mike Gordon

- Edward Gorey

- John Lennon

- Spike Milligan

- Flann O'Brien

- Mervyn Peake

- Jack Prelutsky

- Anushka Ravishankar

- Laura E. Richards

- Theodore Roethke

- Michael Rosen

- Carl Sandburg

- Dr. Seuss

- Shel Silverstein

- James Thurber

- Alan Watts

Writers of nonsense from other languages include:

- Lennart Hellsing (Swedish)

- Zinken Hopp (Norwegian)

- Alfred Jarry (French)

- Christian Morgenstern (German)

- Halfdan Rasmussen (Danish)

- Sukumar Ray (Bengali)

- Mangesh Padgavkar (Marathi)

- Erik Satie (French)

- Daniil Kharms (Russian)

Popular culture

David Byrne, frontman of the art rock/new wave group Talking Heads, employed nonsensical techniques in songwriting. Byrne often combined coherent yet unrelated phrases to make up nonsensical lyrics in songs such as: "Burning Down the House", "Making Flippy Floppy" and "Girlfriend Is Better".[19] This tendency formed the basis of the title for the Talking Heads concert movie, Stop Making Sense.

Syd Barrett, frontman and founder of Pink Floyd, was known for his often nonsensical songwriting influenced by Lear and Carroll that featured heavily on Pink Floyd's first album, The Piper at the Gates of Dawn.[20]

Glen Baxter's comic work is often nonsense, relying on the baffling interplay between word and image.[21]

Zippy the Pinhead, by Bill Griffith, is an American strip that mixes philosophy, including what has been called "Heideggerian disruptions,"[22]and pop culture in its nonsensical processes.[23]

See also

Further reading

Primary sources

- Carroll, Lewis (Charles Lutwidge Dodgson), Alice in Wonderland (1865). ed. Donald J. Gray, 2nd edition. London: Norton, 1992.

_________. The Complete Works of Lewis Carroll. London: Nonesuch Press, 1940.

- Daly, Nicholas. A Wanderer in Og. Cape Town: Double Storey Books, 2005.

- [Eggers, Dave and his brother Christopher] aka Dr. and Mr. Doris Haggis-on-Whey'. Giraffes? Giraffes!, The Haggis-On-Whey World of Unbelievable Brilliance, Volume 1., Earth: McSweeney's, 2003.

_________. Your Disgusting Head: The Darkest, Most Offensive—and Moist—Secrets of Your Ears, Mouth and Nose, Volume 2., 2004.

_________. Animals of the Ocean, In particular the giant squid, Volume 3, 2006

_________. Cold Fusion, Volume 4, 2008- Gordon, Mike. Mike's Corner: Daunting Literary Snippets from Phish's Bassist. Boston: Bulfinch Press, 1997.

- Gorey, Edward. Amphigorey. New York: Perigee, 1972.

_________. Amphigorey too. New York: Perigee, 1975.

_________. Amphigorey Also. Harvest, 1983.

_________. Amphigorey Again. Barnes & Noble, 2002.- Kipling, Rudyard, Just So Stories.New York: Signet, 1912.

- Lear, Edward, The Complete Verse and Other Nonsense. Ed. Vivian Noakes. London: Penguin, 2001.

- Lennon, John, Skywriting by Word of Mouth and other writings, including The Ballad of John and Yoko. New York: Perennial, 1986.

_________. The Writings of John Lennon: In His Own Write, A Spaniard in the Works New York: Simon and Schuster, 1964, 1965.

- Milligan, Spike, Silly Verse for Kinds. London: Puffin, 1968.

- Morgenstern, Christian, The Gallows Songs: Christian Morgenstern's "Galgenlieder", trans. Max Knight. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1963.

- Peake, Mervyn, A Book of Nonsense. London: Picador, 1972.

_________. Captain Slaughterboard Drops Anchor. London: Country Life Book, 1939.

_________. Rhymes Without Reason. Eyre & Spottiswoode, 1944.

_________. Titus Groan. London: , London: Methuen, 1946.- Rasmussen, Halfdan. Hocus Pocus: Nonsense Rhymes, adapted from Danish by Peter Wesley-Smith, Illus. IB Spang Olsen. London: Angus & Robertson, 1973.

- Ravishankar, Anushka, Excuse Me Is This India? illus. by Anita Leutwiler, Chennai: Tara Publishing, 2001.

_________. Wish You Were Here, Chennai: Tara Publishing, 2003.

_________. Today is My Day, illus. Piet Grobler, Chennai: Tara Publishing, 2003.- Richards, Laura E., I Have a Song to Sing You: Still More Rhymes, illus. Reginald Birch. New York, London: D. Appleton—Century Company, 1938.

_________. Tirra Lirra: Rhymes Old and New, illus. Marguerite Davis. London: George G. Harrap, 1933.

- Roethke, Theodore, I Am! Says the Lamb: a joyous book of sense and nonsense verse, illus. Robert Leydenfrost. New York: Doubleday & Company, 1961.

- Rosen, Michael, Michael Rosen’s Book of Nonsense, illus. Claire Mackie. Hove: Macdonald Young Books, 1997.

- Sandburg, Carl, Rootabaga Stories. London: George G. Harrap, 1924.

_________. More Rootabaga Stories.

- Seuss, Dr. On Beyond Zebra!New York: Random House, 1955.

- Thurber, James, The 13 Clocks, 1950. New York: Dell, 1990.

- Watts, Alan, Nonsense. New York: E.P. Dutton, 1975; originally Stolen Paper Review Editions, 1967.

Anthologies

- A Book of Nonsense Verse, collected by Langford Reed, Illus. H.M. Bateman. New York & London: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1926.

- The Chatto Book of Nonsense Poetry, ed. Hugh Haughton. London: Chatto & Windus, 1988.

- The Everyman Book of Nonsense Verse, ed. Louise Guinness. New York: Everyman, 2004.

- The Faber Book of Nonsense Verse, ed. Geoffrey Grigson. London: Faber, 1979.

- A Nonsense Anthology, collected by Carolyn Wells. New York: Charles Schribner's Sons, 1902.

- O, What Nonsense!, selected by William Cole, illus. Tomi Ungerer. London: Methuen & Co., 1966.

- The Puffin Book of Nonsense Verse, selected and illus. Quentin Blake. London: Puffin, 1994.

- The Tenth Rasa: An Anthology of Indian Nonsense, ed. Michael Heyman, with Sumanyu Satpathy and Anushka Ravishankar. New Delhi: Penguin, 2007. The blog for this book and Indian nonsense: [1]

Secondary sources

- Andersen, Jorgen, “Edward Lear and the Origin of Nonsense” English Studies, 31 (1950): 161-166.

- Baker, William, “T.S. Eliot on Edward Lear: An Unnoted Attribution,” English Studies, 64 (1983): 564-566.

- Bouissac, Paul, “Decoding Limericks: A Structuralist Approach,” Semiotica, 19 (1977): 1-12.

- Byrom, Thomas, Nonsense and Wonder: The Poems and Cartoons of Edward Lear. New York: E.P. Dutton, 1977.

- Cammaerts, Emile, The Poetry of Nonsense. London: Routledge, 1925.

- Chesterton, G.K., “A Defence of Nonsense,” in The Defendant (London: J.M. Dent & Sons, 1914), pp. 42–50.

- Chitty, Susan, That Singular Person Called Lear. London: Weidenfeld and Nicholson, 1988.

- Colley, Ann C., Edward Lear and the Critics. Columbia, SC: Camden House, 1993.

_________. “Edward Lear’s Limericks and the Reversals of Nonsense,” Victorian Poetry, 29 (1988): 285-299.

_________. “The Limerick and the Space of Metaphor,” Genre, 21 (Spring 1988): 65-91.- Cuddon, J.A., ed., revised by C.E. Preston, “Nonsense,” in A Dictionary of Literary Terms and Literary Theory, 4th edition (Oxford: Blackwell, 1976, 1998), pp. 551–58.

- Davidson, Angus, Edward Lear: Landscape Painter and Nonsense Poet. London: John Murray, 1938.

- Deleuze, Gilles, The Logic of Sense, trans. Mark Lester with Charles Stivale, ed. Constantin V. Boundas. London: The Athlone Press, (French version 1969), 1990.

- Dilworth, Thomas, “Edward Lear’s Suicide Limerick,” The Review of English Studies, 184 (1995): 535-38.

_________. “Society and the Self in the Limericks of Lear,” The Review of English Studies, 177 (1994): 42-62.

- Dolitsky, Marlene, Under the Tumtum Tree: From Nonsense to Sense. Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 1984.

- Ede, Lisa S., “The Nonsense Literature of Edward Lear and Lewis Carroll”. unpublished PhD dissertation, Ohio State University, 1975.

_________. “Edward Lear’s Limericks and Their Illustrations” in Explorations in the Field of Nonsense, ed. Wim Tigges (Amsterdam: Rodopi, 1987), pp. 101–116.

_________. “An Introduction to the Nonsense Literature of Edward Lear and Lewis Carroll” in Explorations in the Field of Nonsense, ed. Wim Tigges (Amsterdam: Rodopi, 1987), pp. 47–60.- Flescher, Jacqueline, “The language of nonsense in Alice,” Yale French Studies, 43 (1969–70): 128-44

- Graziosi, Marco, “The Limerick” on Edward Lear Home Page (http://www2.pair.com/mgraz/Lear/index.html)

- Guiliano, Edward, “A Time for Humor: Lewis Carroll, Laughter and Despair, and The Hunting of the Snark” in Lewis Carroll: A Celebration, ed. Edward Guiliano (New York, 1982), pp. 123–131.

- Haight, M.R., “Nonsense,” British Journal of Aesthetics, 11 (1971): 247-56.

- Hark, Ina Rae, Edward Lear. Boston: Twayne Publishers, 1982.

_________. “Edward Lear: Eccentricity and Victorian Angst,” Victorian Poetry, 16 (1978): 112-122.

- Heyman, Michael, Isles of Boshen: Edward Lear in Context. PhD dissertation, University of Glasgow, 1999. [2]

_________. "A New Defense of Nonsense; or, 'Where is his phallus?' and other questions not to ask" in Children's Literature Association Quarterly, Winter 1999-2000. Volume 24, Number 4 (186-194)

_________. "An Indian Nonsense Naissance" in The Tenth Rasa: An Anthology of Indian Nonsense, edited by Michael Heyman, with Sumanyu Satpathy and Anushka Ravishankar. New Delhi: Penguin, 2007.- Hilbert, Richard A., “Approaching Reason’s Edge: ‘Nonsense’ as the Final Solution to the Problem of Meaning,” Sociological Inquiry, 47.1 (1977): 25-31

- Huxley, Aldous, “Edward Lear,” in On the Margin (London: Chatto & Windus, 1923), pp. 167–172

- Lecercle, Jean-Jacques, Philosophy of Nonsense: The Intuitions of Victorian Nonsense Literature. London, New York: Routledge, 1994.

- Lehmann, John, Edward Lear and his World. Norwich: Thames and Hudson, 1977.

- Malcolm, Noel, The Origins of English Nonsense. London: Fontana/HarperCollins, 1997.

- McGillis, Roderick, "Nonsense," A Companion to Victorian poetry, ed. by Richard Cronin, Alison Chapman, and Anthony Harrison. Oxford: Blackwell, 2002. 155-170.

- Noakes, Vivien, Edward Lear: The Life of a Wanderer, 1968. Glasgow: Fontana/Collins, revised edition 1979.

_________. Edward Lear, 1812-1888. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1985.

- Nock, S. A., “Lacrimae Nugarum: Edward Lear of the Nonsense Verses,” Sewanee Review, 49 (1941): 68-81.

- Orwell, George, “Nonsense Poetry” in Shooting an Elephant and Other Essays. London: Secker and Warburg, 1950. pp. 179–184

- Osgood Field, William B., Edward Lear on my Shelves. New York: Privately Printed, 1933.

- Partridge, E., “The Nonsense Words of Edward Lear and Lewis Carroll,” in Here, There and Everywhere: Essays Upon Language, 2nd revised edition. London: Hamilton, 1978.

- Prickett, Stephen, Victorian Fantasy. Hassocks: The Harvester Press, 1979.

- Reike, Alison, The Senses of Nonsense. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 1992.

- Robinson, Fred Miller, “Nonsense and Sadness in Donald Barthelme and Edward Lear,” South Atlantic Quarterly, 80 (1981): 164-76.

- Sewell, Elizabeth, The Field of Nonsense. London: Chatto and Windus, 1952.

- Stewart, Susan, Nonsense: Aspects of Intertextuality in Folklore and Literature. Baltimore: The John’s Hopkins UP, 1979.

- Tigges, Wim, An Anatomy of Literary Nonsense. Amsterdam: Rodopi, 1988.

_________. “The Limerick: The Sonnet of Nonsense?” Dutch Quarterly Review, 16 (1986): 220-236.

_________. ed., Explorations in the Field of Nonsense. Amsterdam: Rodopi, 1987.- van Leeuwen, Hendrik, “The Liaison of Visual and Written Nonsense,” in Explorations in the Field of Nonsense, ed. Wim Tigges (Amsterdam: Rodopi, 1987), pp. 61–95.

- Wells, Carolyn, “The Sense of Nonsense,” Scribner’s Magazine, 29 (1901): 239-48.

- Willis, Gary, “Two Different Kettles of Talking Fish: The Nonsense of Lear and Carroll,” Jabberwocky, 9 (1980): 87-94.

- Wullschläger, Jackie, Inventing Wonderland, The Lives and Fantasies of Lewis Carroll, Edward Lear, J.M. Barrie, Kenneth Grahame, and A.A. Milne. London: Methuen, 1995.

Notes

- ^ Tigges, Anatomy, p. 255.

- ^ Heyman, Boshen, pp. 2-4

- ^ Malcolm, p. 4.

- ^ Malcolm, pp. 6-7.

- ^ Malcolm, p. 14.

- ^ Tigges, Anatomy, pp. 166-167.

- ^ Heyman, Naissance, pp. xxvi-xxix

- ^ Lecercle, p. 29.

- ^ Lecercle, p. 64.

- ^ Tigges, p. 2.

- ^ Tigges, p. 81.

- ^ Anderson, p. 33.

- ^ Tigges, pp. 108-110.

- ^ Sandburg, p. 82.

- ^ Tigges, Anatomy, p. 95.

- ^ Carroll, p. 55.

- ^ "Cabaret and Jazz Songs by Dennis Livingston". http://www.dennislivingston.com/jl_mairzy.htm. Retrieved 24 April 2010.

- ^ Malcolm, p. 127.

- ^ http://catharsis.tumblr.com/post/465840647/david-byrne-on-musical-collaborations

- ^ O'Hagan, Sean (25 April 2010). "Syd Barrett: A Very Irregular Head by Rob Chapman". The Guardian (London). http://www.guardian.co.uk/music/2010/apr/25/syd-barrett-irregular-head-review. Retrieved 24 April 2010.

- ^ Pereira, pp. 189-195

- ^ Grabiner, July/Aug, 2011

- ^ Lecercle, p. 108-109

References

- Carroll, Lewis (1865). Alice's adventures in wonderland. Macmillan. http://books.google.com/books?id=CLoNAAAAYAAJ.

- Celia Catlett Anderson; Marilyn Apseloff (1989). Nonsense literature for children: Aesop to Seuss. Library Professional Publications. ISBN 9780208021618. http://books.google.com/books?id=QrtlAAAAMAAJ.

- Chomsky, Noam (2002). Syntactic structures. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 9783110172799. http://books.google.com/books?id=a6a_b-CXYAkC.

- Grabiner, Ellen (2011). The Heideggarian Disruptions of Zippy the Pinhead. Philosophy Now. http://www.philosophynow.org/issue84/The_Heideggerian_Disruptions_of_Zippy_The_Pinhead.

- Heyman, Michael (2007). "An Indian Nonsense Naissance" in The Tenth Rasa: An Anthology of Indian Nonsense. New Delhi: Penguin. ISBN 0143100866.

- Heyman, Michael Benjamin (1999). Isles of Boshen: Edward Lear's literary nonsense in context. Scotland: Glasgow. https://dspace.gla.ac.uk/handle/1905/330.

- Lecercle, Jean-Jacques (4 April 1994). Philosophy of nonsense: the intuitions of Victorian nonsense literature. Routledge. ISBN 9780415076531. http://books.google.com/books?id=98fiZnOEy9gC.

- Malcolm, Noel (1997). The origins of English nonsense. HarperCollins. http://books.google.com/books?id=qWkgAQAAIAAJ.

- Pereira, Conceição (2005). Glen Baxter: simulacro e literalização. Porto: Faculdade de Letras, Universidade do Porto.

- Sandburg, Carl (1922). Rootabaga stories. Harcourt, Brace and Company. http://books.google.com/books?id=EEMeAAAAMAAJ.

- Tigges, Wim (1988). An anatomy of literary nonsense. Rodopi. ISBN 9789051830194. http://books.google.com/books?id=oWZdgvSJ3bgC.

External links

Categories:- Humanities

- Literary genres

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.