- Barking Owl

-

Barking Owl

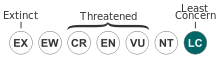

Conservation status Scientific classification Kingdom: Animalia Phylum: Chordata Class: Aves Order: Strigiformes Family: Strigidae Genus: Ninox Species: N. connivens Binomial name Ninox connivens

(Latham, 1802)The Barking Owl (Ninox connivens), also known as the Barking Boobook or Winking Owl, is a nocturnal bird species native to mainland Australia and parts of Papua New Guinea. They are a medium-sized brown owl and have an extremely characteristic voice that can range from a barking dog noise to a shrill woman-like scream of great intensity. Barking owls are often said to be the source to the myths and legends surrounding the Bunyip.

Contents

Taxonomy

The Barking Owl was first described by ornithologist John Latham in 1802.

Description

The Barking Owl is coloured brown with white spots on its wings and a streaked chest. They have large eyes that have a yellow iris, a dark brown beak and almost no facial mask. Their underparts are brownish-grey and coarsely sotted white with their tail and flight feathers being moderately lighter in colour. They are a relatively medium sized owl and their wingspan is between 85–100 cm in length. They weigh between 425 and 510g and size varies only slightly between the male and female birds with the male Barking Boobook being larger.

Habitat

The Barking Owl lives in Mainland Australia off the Eastern and Northern coast of the continent including areas surrounding Perth. They also live in Parts of Papua New Guinea and the Moluccas. Once widespread, Barking Owls are now less common in mainland Australia.

They choose to live in forests or woodland areas that have large trees for nesting and roosting. They mostly choose to live near river, swamp or creek beds as they are attracted to water. It is because they live in such places which include billabongs they have been mistaken for the mythical creature, the Bunyip. Bunyips, according to legend are said to inhabit creeks and lonely river beds in the Australian Bush.

Although Barking Owls are uncommon and sometimes even rare in many suburban areas it is not unheard of that they get accustomed to humans and even start to nest in streets or near farm houses.

Voice

Most people hear the Barking Owl rather than see it as it has an explosive voice unlike many other Australian owl species. It has a double dog bark and various growls that so closely mimic the real thing[vague] it is nearly impossible to tell the difference. It has so been named because of these noises. Barking and growling is more common than the screaming of the barking owl.

The screaming of the Barking Owl is said to sound like a woman or child screaming in pain. Hearings of 'screaming lady,' as it is so nicknamed, are very rare and many only hear the sound once in their life even if they live next to a Barking Owl nest. The actual significance of the sound is unknown; though many myths surround the events that caused the owl to originally "mimic" the sounds.

In the early settlement of Australia a screaming noise matching the Barking Owl's description was credited and told to the settlers by the Indigenous Australians or the Aboriginals as the Bunyip. The Bunyip was said to be a fearsome creature that inhabited swamps, rivers and billabongs. Bunyips had many different descriptions but most were of an animal of some sort whose favorite food was that of human women. The cries and noises coming from swamps and creeks at night were not said to be the victims but actually the noise the Bunyip made. It is believed by many that the sound is of the nocturnal Barking Owl and that proves the location, the noises and the rarity of the Bunyip cries. It is still not proven though that the Barking Owl actually started the Bunyip story and it could be caused from other sources. But it seems that the Barking Owl will stay as the most likely explanation.

Conservation status

Barking Owls are not listed as threatened on the Australian Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999. However, their conservation status varies from state to state within Australia. For example:

- The Barking Owl is listed as threatened on the Victorian Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act (1988).[1] Under this Act, an Action Statement for the recovery and future management of this species has been prepared.[2]

- On the 2007 advisory list of threatened vertebrate fauna in Victoria, the Barking Owl is listed as endangered.[3]

- The Barking Owl is listed as 'Vulnerable' under the NSW Threatened Species Conservation Act (1995).[4]

Decline and extent

In the State of Victoria, according to Action Statement 116 issued under the FFG Act "The Barking Owl is the most threatened owl in Victoria. The population has been estimated to be fewer than 50 breeding pairs (Silveira et al. 1997), though recent work in north-eastern Victoria (Taylor et al. 1999; N. Schedvin pers. comm.) suggests that this estimate will need to be revised upwards. Existing records of Barking Owls on the Atlas of Victorian Wildlife database (NRE 2001) are unlikely to give an accurate representation of the current distribution and abundance of the species. Many of these records are dated, occurring in areas where once-suitable habitat has been lost or degraded. Extensive surveys in Victorian forests have shown the species to be rare, localised and mainly found in north-eastern Victoria (Loyn et al. 2001)."

Threatening processes

According to the Action Statement No. 116 made under the FFG Act, in the state of Victoria the primary threat to the Barking Owl is loss of habitat, particularly the deterioration or loss of the large, hollow-bearing trees on which the species depends for nesting. Hollows suitable for nesting for owls do not form in eucalypts until they are at least 150–200 years old (Parnaby 1995). Similarly, hollows are an important resource for many prey species of the Barking Owl, e.g. gliders and possums. Such trees are not being regrown rapidly enough to exceed expected losses in the next century. The removal of dead, standing trees and stags for firewood is also likely to remove nesting sites for the species (E. McNabb pers. comm.). Native prey species such as arboreal mammals and hollow-nesting birds have declined in some areas through clearing of native vegetation, loss of hollows and the impact of introduced predators. These declines may also have contributed to the decline of the Barking Owl, although in some areas European Rabbits have become a substitute prey, and local populations of the Barking Owl have become heavily dependent upon them. It is not known how the owls will fare through periods of Rabbit decline due to climate fluctuations, control programs or disease such as calicivirus. Where poisons are used to control Rabbits, secondary poisoning of owls may be an issue.

References

- ^ Department of Sustainability and Environment, Victoria

- ^ Department of Sustainability and Environment, Victoria

- ^ Victorian Department of Sustainability and Environment (2007). Advisory List of Threatened Vertebrate Fauna in Victoria - 2007. East Melbourne, Victoria: Department of Sustainability and Environment. p. 15. ISBN 978-1-74208-039-0.

- ^ NSW Scientific Committee Final Determination of Barking Owl

- BirdLife International (2004). Ninox connivens. 2006. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. IUCN 2006. www.iucnredlist.org. Retrieved on 12 May 2006.

External links

- Owl Pages information

- Barking Owl, Queensland Environmental Protection Agency (includes audio of a Barking Owl)

- Barking Owl videos, photos & sounds on the Internet Bird Collection

- NSW Scientific Committee Final Determination for Barking Owl

Categories:- IUCN Red List least concern species

- Ninox

- Birds of South Australia

- Birds of Western Australia

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.